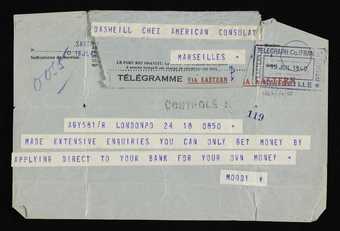

Harold Moody, recipient: Ronald Moody

Letter from [Harold] Moody to [Ronald Moody] ([19 July 1940])

Tate Archive

Making the Case for Support

Joseph Bard

Photograph of Eileen Agar balancing on a beam at the beach (September 1938)

Tate Archive

For those seeking external funding for an archive digitisation project, your first step will be to secure your supporters. To do this, you'll need to write a case for support, which summarises the vision for your project and why people should invest in it.

There are lots of online resources that can help you create a strong and compelling document. The Archives & Access case for support was written from the perspective of those who would benefit from the project and explained how our digitisation programme would transform people’s enjoyment and understanding of archive collections. We also thought carefully about how we could explain our plans to engage and involve people who had no previous experience of archives.

future ambitions

One of the most important things is to be able to say what will change as a result of your project, or what difference your project will make to the people involved. Many of us are so involved in the details of our projects that we spend too much time explaining to others what they will do, and not what their benefits will be. Consider the difference between ‘This ambitious project will work with 80 volunteers across the UK’ and ‘This ambitious project will help people to learn new skills, increase their well-being and find out more about the places where they live and work’.

We were ambitious in our plans for Archives & Access. This ambition made our project attractive to potential donors, who were excited by our aim to lead the sector in this activity and to develop a long-term infrastructure at Tate that would facilitate future projects. There is a tendency to assume that asking a funder for modest sums of money will give a greater chance of success, but often donors are actually looking for projects that will be a catalyst for changing the way that an organisation – or even the entire sector – does something.

Yes's and no's

Fundraising can be tough and you need to be persistent and resilient. It takes a long time to develop donor relationships or to make formal funding applications, especially if you’re first ask isn’t successful, so make sure you plan sufficient time for these activities at the outset of your project. To do this, it is vital to include development staff (or those with a fundraising remit) from the very beginning of your project planning. Remember to manage the expectations of colleagues and stakeholders about how long it will take you to secure funding, so that you can keep momentum and morale up.

The principle of nine fundraising no's, developed by Bernard Ross and Clare Segal, can be a helpful tool for reviewing any fundraising rejections and thinking about next steps.

All good fundraising should be about developing effective partnerships. Once you’ve secured the funding for your project, remember not only to thank your supporters in anything you do, but also to include them in your activities and keep them up to date if plans change.

Structuring the team

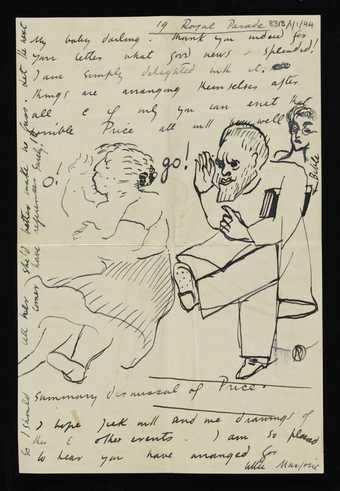

Paul Nash, recipient: Margaret Nash

Letter from Paul Nash to Margaret Odeh written from 19 Royal Parade, Cheltenham (26 September 1913)

Tate Archive

Once you have secured project funding, you will need to assemble and structure the delivery team. Digitisation schemes are highly collaborative, and require the input from many areas of expertise. Archives & Access, for instance, required the involvement of thirteen different Tate departments, and at the time of inception was the largest interdepartmental project we had run. There is plenty of information about out-of-the-box and tailored project management systems available online: Prince2, Waterfall, Agile, Wagile... So invest time in researching which approach will suit your needs best.

Governance

Archives & Access was governed by an embedded project director's board. The board members were director-level representatives for all project stakeholders, and included a designated project lead, and a project sponsor. The board were responsible for making strategic decisions in relation to the project. In order to do this, the director's board met quarterly, where they received updates on project progress from the project manager.

Project management

Our project manager was recruited specifically to deliver Archives & Access. They were responsible for ensuring that the project plan was adhered to, that milestones were reached (or if not, were mitigated), and for budget control and risk management. As well as reporting to directors, the project manager prepared updates on project progress submitted to our funders every quarter.

And it was the project manager, with the support of the project lead, who coordinated the project delivery team – the core and contracted staff responsible for delivering the project. The team comprised at least one representative from each of the thirteen departments involved in Archives & Access.

Communication and consensus

To facilitate communication across and collaboration between a large and diverse project team, we decided to run delivery team meetings fortnightly. At these meetings, team members would update on progress, cross-check upcoming activities as appropriate, as well as share practice and knowledge in support of the project workflow. This approach proved highly beneficial, keeping team members up to speed with project developments and allowing the group to tackle issues arising without undue delay.

The project manager and the Archives & Access learning staff also coordinated outreach activities in collaboration with the project's five national learning partners in a 'hub and spoke' formation.

This approach to project management not only supported the delivery of Archives & Access, but also resulted in longer–term organisational change: with departments acquiring a greater understanding of each others' working practices. This shift in organisational culture has in turn facilitated the project's succession, by ensuring that the digitisation infrastucture and processes are familiar and embedded as 'business as usual'.