Nigel Henderson

Photograph of Freda Paolozzi ([c.1950s])

Tate Archive

How, why, what and who

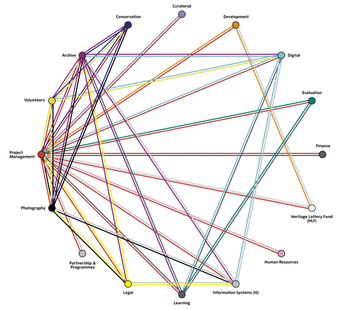

Digitisation processes, or 'workflows' – the steps taken in order to get collections digitised and published – are invariably complex. Moreover, workflows will differ from one institution to another, as they will be designed and implemented to suit specific requirements – in response to such things as databases used, personnel available, scope of work, among other contingencies.

If digitisation is viewed as a long-term commitment, then it follows that workflows benefit from being designed with longevity in mind. To best serve audiences, and to support the parent institution, digitisation workflows – just like the programmes of work they are designed to deliver – should be researched, resourced, robust and resilient.

Paul Nash, recipient: Eileen Agar

‘Aerial Flowers’, by Paul Nash (1947)

Tate Archive

Planning ahead

In our case, we scoped the succession plan and legacy outcomes for Archives & Access prior to bid submission. Put simply, the long–term goal was to create a robust and resilient workflow that would support archive digitisation activities beyond the run of the project, with costs attributed accordingly. As a result Archives & Access secured a grant that allowed funds to be invested in both workflow infrastructure, the hardware and software, and staff training and development.

Accessible, or accessed?

Further, the bid detailed a project that undertook digitisation and publication delivered in conjunction with learning and outreach activities. This approach was taken in order to ensure the published collections reached widened audiences: that the collections were not simply accessible, but accessed (read more about the project's outreach activities).

We already knew from working with local school and community groups that we had a rich collection with lots of potential. However, pre-project much of our evidence was anecdotal. To understand audience needs better, we commissioned an external agency to undertake a series of focus groups with our target audiences. We also drew on external evaluation and research from across the sector, including research commissioned by the HLF, to situate our project in the wider context of online engagement and participation.

Gathering this evidence both helped us determine the project scope and detail what we needed – in terms of technical infrastructure and staff know-how – to deliver the vision and ensure the project had a productive legacy.

Outcomes

By investing in hardware and software purchases, which included setting up the High Value Digital Asset (HVDA) storage (which has been further developed through other projects for the digital preservation of artworks), and a digitisation imaging suite in photography, Archives & Access increased our capacity to digitise in the long-term.

By investing in staff training, we were endowed with a skilled and inter-connected workforce able to continue archive digitisation activity once the Archives & Access project activity had concluded.

The delivery of digitisation in conjunction with outreach informed the selection criteria, and helped shape the production of a range of digital tools developed to encourage discovery of the published collections.

This meant that the project would become a programme upon completion, and that the workflow would be embedded as business as usual.

Further, through encouraging conversation and practice sharing, the project helped us to engage more deeply with sector-wide digitisation activity. We have found it particularly useful to discuss, troubleshoot, and reflect with colleagues undertaking a wide range of digitisation schemes. No two archive digitisation projects will be exactly alike, but by sharing knowledge, experience, and visions, we can aim as a sector, to develop our resilience, capacity and expertise as we engage in this inherently collaborative field.

Recommendations

Below are a series of recommendations derived from our experience with the Archives & Access digitisation and outreach project. You will find a range of guidance, from advice on designing a suitable digitisation workflow, to information about how we selected material for digitisation, as well as pointers on image capture, legal issues to be aware of, and the approach we took to subject indexing the collections published.

Archive cataloguing

The Archives & Access project adopted and adapted extant back-end cataloguing and IT systems to enable archive digitisation to happen within existing channels at Tate. This approach was taken to produce a sustainable outcome: rather than designing workflows to suit one–off digitisation projects, the workflow developed for Archives & Access would serve our future digitisation activities.

This required Tate Archive images and metadata to be integrated into the existing technical architecture for publishing the art collection online, and for the records to be published via the front-end interface. Though this approach presented a number of technical challenges, the integration of artworks and archive materials ensured that the archive pieces would be more readily surfaced in search results and would benefit from future functionality and design updates rolled out across the website.

challenges and solutions

Archive data is catalogued in a different way from that relating to artworks in our collection: artworks are catalogued as single artefacts, whereas archive materials are catalogued hierarchically (where similar types of items are grouped together in series, and cataloguing information is placed at the most appropriate level of the catalogue).

We decided to draw the archive cataloguing information from CALM – its native database – into TMS, where the artworks are catalogued. In doing this, we had all the information about the digitised pieces located within one database. However, this process required us to map fields in CALM to match those in TMS, to make sure that the same information was in the correct place in both systems. In order to do this, a script was written to pull the information from one database into the other. This meant that all the archive material for digitisation was manually catalogued so that every single piece had an individual reference number. This was a time-consuming process, but it enabled the data to be transferred from CALM to TMS and then on to iBase Manager. This meant that all the cataloguing records were in the image management system – including handling instructions from the conservators and any requests to redact information – enabling exact matching of the images to the catalogue.

Recommendations from the archive team

- If following a comparable method to the above, do not underestimate the need to check original cataloguing (as the project progressed, we discovered that there were more legacy cataloguing issues than we had first imagined)

- Think carefully about what exactly you want to do as you design your approach: do you need to capture everything, or would excluding the more complex or most fragile items create a much simpler workflow?

- Make sure there is enough contingency, in both budget and time

- Do not underestimate the impact on time staff changes will have; do not assume everyone will stay for the duration of their contracts

- Acknowledge that errors will be made, and make sure the workflow is designed to accommodate this

- Think about the project team in term of a forum for communication and collaboration: a chance to learn about your colleagues working practices

- Do not underestimate how much of an impact a large digitisation project will have on the day-to-day running of the archive - if digitisation is a priority, make sure that this is acknowledged and understood

- Make sure everyone has access to all the databases and someone knows how to use every system in the workflow