A poor condition painting

John Brett’s The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871 was presented to Tate by Mrs Brett on the artist’s death in 1902. In recent years it had remained in store because of its poor condition. In particular, a thick layer of very discoloured varnish and dirt obscured much of the image.

The exhibition Pre-Raphaelite Vision: Truth to Nature at Tate Britain in 2004 provided an opportunity to revisit this painting and to spend some time recovering it for display.

Researching the artist’s technique

Fig 1. John Brett, The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871.

Oil on canvas. Support: 1060 x 2127 mm

frame: 1390 x 2458 x 121 mm, painting

© Tate London, 2005. Before treatment

Brett’s technique in this painting differs from his earlier methods, as seen for example in the painstakingly constructed Glacier of Rosenlaui 1856 or Florence from Bellosguardo 1863. These works are much closer in intention and technique to works by the artists involved with the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and directly reflects the teaching of John Ruskin. In the later seascape, however, Brett seems to have been developing a method to combat some of the self-imposed limitations of painting in the Pre-Raphaelite way.

In spite of the discoloured varnish, it was possible to see Brett’s uncharacteristic technique for The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs. Brett achieved texture not through precise brushwork but instead using mechanical methods. Principally, this involved the application of a layer of textured ground, over which he applied a thin layer of paint which seems to have been partly resisted or repelled by the underlayer. Brett exploited this reluctance of the two layers to wet one another to create visual ‘noise’ across the composition. The result is a paint film that resembles the surfaces of impressionist and post-impressionist paintings albeit achieved by different methods.

Impact of technique on the conservator’s work

Fig 2. John Brett, The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871.

During varnish removal

It was clear that this technique would present problems for conservators cleaning the painting. The problem for the restorer is not knowing exactly how the artist modified his oil paints to achieve the results he desired.

A paint layer that fails to wet the one underneath may be inclined to separate from it during cleaning and the removal of the varnish. Furthermore, as in this case, a uniform application of paint across a large painting reduces the tolerances for any variation in cleaning. The difficulty of reading the image through the deeply yellowed varnish raised concerns that subtle glazes or variations might not be discerned. Whenever a varnish is that discoloured, it is wise to ask why. Was the coating perhaps intentionally coloured to hide some flaw in the artist’s execution, or some later damage?

A useful comparison with other works

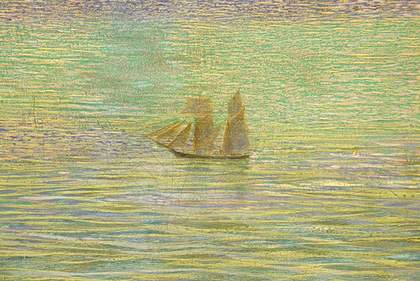

Fig 3. John Brett, The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871.

Detail of reflections in the sea

Fig 4. John Brett, The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871

Detail of sky and clouds

Fig 5. John Brett, The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871.

Detail of sea showing brushed and dabbing technique

Fortunately, there exist similar works by the artist that are in good condition and conservators were confident that the original state of this painting was well worth trying to restore.

The removal of an almost orange varnish (in fact, three layers of dirt interspersed with three layers of degraded varnish) from the blue-green paint film resulted in a most dramatic colour change. The photographs taken before treatment during varnish removal and after treatment are clear evidence of the change.

Understanding the painting with fresh eyes

With cleaning, it is now possible to appreciate the painting properly. The painting depicts the English Channel seen from the Dorset cliffs, looking directly into a sun partly obscured by clouds and distributing its rays across the surface of the shimmering sea. It is these atmospheric and optical effects that Brett was interested in, not the detail of the scene.

To paint the seascape, Brett began with a pre-prepared white primed canvas, purchased from a colourman’s shop. He then gave it a fresh coat of lead white, in the Pre-Raphaelite manner, before applying a pale pink wash across the horizon in the sky and sea to provide the dominant tone for the painting. He gave the layer of white paint a fine texture like that from a flock roller. Although it is conjecture, conservators are of the opinion that Brett then allowed this layer to dry thoroughly until it developed a solid glossy surface. Applying a thin layer of fresh oil paint to this surface would result in the poor wetting. Presumably Brett did this deliberately. The result is repetitive and in some ways mechanical, but it provided an overall texture that is characteristic of the painting and would have been very time-consuming to generate another way.

Fig 6. John Brett, The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs 1871

Restored painting and frame

Within this broad outline Brett has composed his picture, creating reflections across the sea using a variety of painterly devices. The sky, predominantly a single coat of lead white and ultramarine, was formed by the application of an even wash and then by removing or dispersing areas of wet paint, perhaps using a cloth or sponge, to produce the pale pink and white clouds. This is very much analogous to watercolour technique. The sea is more complex. The foreground involves strokes of cobalt blue, washes of viridian, cobalt and white and lighter passages of more opaque paint to depict the sunlight on the surface of the sea. Towards the horizon the paint was applied in isolated dabs of colour in a purely impressionistic technique. The poor wetting has caused the dabs to separate on the surface and the isolation of each dab has become more evident over time by the contraction of the paint around it.

References

- Joyce Townsend, Jacqueline Ridge and Stephen Hackney, (eds), Pre-Raphaelite Painting Technique, Tate Publishing, London 2004.

- Kate Lowry, ‘A Technical Note on Brett’s Paintings’ in John Brett: A Pre-Raphaelite on the Shores of Wales, National Museum and Gallery of Wales, Cardiff 2001, pp.38–42.