Fig.1

David Lucas after John Constable

Weymouth Bay, Dorsetshire published 1830, from English Landscape 1830–2

Mezzotint

Image: 144 × 182 mm

Tate

In May 1833 the Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences featured a full-page advertisement for a set of mezzotints now known as English Landscape (fig.1). The notice was written and placed by the artist John Constable, and was an adaptation of the text he used for the edition’s preface.1 He describes it as ‘a Collection of Prints of Rural Landscape’ being ‘most respectfully offered to the notice of Admirers of Art’:

It is the desire of the Author in this publication to increase the interest for, and promote the study of, the Rural Scenery of England, with all its endearing associations, its amenities, and even in its most simple localities; England, with her climate of more than vernal freshness, in whose summer skies ‘of thousand liveries light’ and rich autumnal clouds, the observer of Nature may daily watch her endless varieties of effect.

Constable states his hope that his work will ‘find a place not only in the portfolio of the Artist, and be an acquisition to the amateur, but, from the almost universal esteem in which the elegant arts are now held, he [the Author] trusts it may prove more generally acceptable.’ He also highlights that the publication is widely available, sold at his house, by his dealer Colnaghi, and by all the principal print sellers. Constable was careful with the wording.2 He had written to his children’s tutor Charles Boner, who had helped him with the project: ‘I wish to avoid all words that might look pompous, or too assuming … I want to assume nothing’3 and to his engraver, David Lucas: ‘you know my work will not explain itself’.4

Fig.2

David Lucas after John Constable

A Heath published 1831, from English Landscape 1830–2

Mezzotint

Image: 141 × 190 mm

Tate

While Constable wanted to assume no knowledge on the part of those who might encounter English Landscape, perhaps we now have too much. Art historians seem compelled to assess the dark mezzotints in relation to Constable’s paintings and as expressive of his mood, their brooding tonalities somehow anticipating their poor sales and what has been perceived as the failure of the project as a whole (fig.2).5 Constable’s print series has almost always been treated separately from the wider culture of printed texts and images in the nineteenth century; they are seen as an exception that instead needs to be understood in connection with Constable’s personal development as an artist or with the larger cultural history of landscape painting of the time. The implication has been that Constable’s more personal, more ambitious engagement with natural scenery is fundamentally incompatible with the (supposedly) more mundane, aesthetically limited and commercially motivated concerns of topographical publication. Moreover, it has generally been asserted that the series should be assessed as a commercial and professional failure. As art historians Ian Fleming Williams and Leslie Parris observed in their 1984 study The Discovery of Constable: ‘Neglect and misunderstanding of his paintings had spurred him to produce this epitome of, and apologia for his art. In the short term English Landscape did very little to extend the public for Constable’s art. Estimates of the numbers of sets disposed of, and whether by gift or sale, range from about forty to less than a hundred.’6

Consciously or not, English Landscape has been placed within a linear narrative of Constable’s life and interpreted in connection with an agenda on the part of the artist as he sought personal gain or professional dominance. It has been tacitly assumed that the ways in which his art is encountered now – celebrated in gallery contexts and filed carefully in the pristine conditions of museum print rooms – represented his ultimate goal. This essay sets out to provide an alternative view, one arguably more revealing of the historical situation of English Landscape, by considering this print series in the context of early nineteenth-century topographical printing.

Resituating English Landscape

The idea of the romantic, inspired, autonomous artist was emerging within Constable’s lifetime, with value being placed on artistic freedom rather than the ability to fulfil commercial obligations. Constable, with Turner and Blake, is one of the big names of British Romantic art.7 But gathering these and other artists together in this way, in association with an idea of artistic freedom arising at this historical moment, risks overlooking the material conditions of possibility that were necessary for their pursuits. With Constable, in particular, it may distract from the far more complex relationship that this artist had with his profession, a theme that literary historian Trev Broughton has been able to explore through careful reference to Constable’s extensive family correspondence.8 On the one hand, Constable’s family sometimes viewed the insecurity of his vocation as a problem; on the other, his contemporaries in the London art world were prone to viewing him as a virtual amateur, given his affluent family background: his father was a mill owner and merchant aspiring to gentry status. Indeed, the very idea of professionalisation in the artistic field was fraught with contradictions.9 The distinctions between commercial self-interest and artistic freedom, professional self-promotion and disinterest, and between the professional and amateur, were much less obvious or clear-cut to Constable and his contemporaries than they are presented by many later commentators.

To a degree, the dominant modern readings of English Landscape are complicit with the perspective promoted by the artist himself. Constable claims that the collection ‘originated in no mercenary views, but merely as a pleasing professional occupation, and was continued with a hope of imparting pleasure and instruction to others. He [the Author] had imagined to himself an object in art, and had always pursued it.’10 When considered as an artist’s publication, English Landscape served several purposes that were not necessarily mercenary, commercial or money-making in nature. But in this regard the series was not only a manifestation of Constable’s inner life or his artistic enterprise, complex and compromised as these may have been. It was also much more like other print projects than is usually allowed.

Here I want to question what English Landscape was and position the series more fully in relation to image production of the time, so as to reconsider its form and its contemporary reception. As scholar and critic Rita Felski has written, while ‘Works of art, by default, are linked to other texts, objects, people and institutions in relations of dependency, involvement and interaction’, it does not follow that every work or text should be ‘deciphered as a symptom, mirror, index, or antithesis of some larger social structure’.11 Perhaps we should aim to ‘assume nothing’, as Constable intended, and try to encounter or experience English Landscape without prejudice or prior knowledge. Questioning dominant or singular biographical readings, the present study calls for a reassessment of our understanding of English Landscape as a project, on new and more appropriate terms than those that have previously been applied. Importantly, this means rethinking how print publication functions in cultural terms, not only commercially but also in articulating the values and expectations of its makers and consumers. This is because printmaking occupies a complex and conflicted position as a mode of cultural production, situated between the worlds of publishing and the art world, the personal and the collaborative, scholarship and commerce, and, in its subsequent historiographical and museological life, between the library, the print room and the art museum.

Topographical printing in the early nineteenth century

The term ‘topography’ has been used in modern art historical literature to refer to an ostensibly stable body of relatively affordable, aesthetically unambitious and straightforwardly descriptive images of place. But as cultural historian John Barrell has shown, ‘topography’ was generally a form of literature rather than an inferior form of landscape painting in Constable’s time. As such, the term could ultimately be seen as a value that indicates rich local knowledge. Discussing a passage from the writer Archibald Alison’s influential Essays on the Nature and Principles of Taste (1810) – a text that was given a canonical role in the emergence of more obviously imaginative and formally ambitious landscape painting – Barrell concludes that:

The more familiar you become with an area, argues Alison, the more it will cease to be appreciated aesthetically, as a landscape, and the more the objects in it will be thought of instrumentally; and that is for Alison the difference between landscape and topography, perhaps between a landscape and a place … [I]t implies the terms for a counter argument that would claim that the very value of topography is that it is a way of knowing and understanding a place ... as it would have appeared, as it would have been known and understood, as a place, by the local inhabitants.12

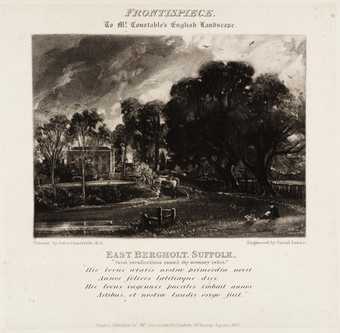

By employing a format familiar from topographical literature – plates with descriptive texts, as exemplified by works by Joseph Farington,13 William Green14 and Charles Heath15 – Constable may have intended English Landscape to convey Alison’s sense of place, of specificity built on rich local knowledge. The letterpress (typeset text) accompanying his mezzotint frontispiece of East Bergholt, Suffolk (fig.3), where the artist grew up, can be read in this light: ‘As this work was begun and pursued by the Author solely with a view of his own feelings, as well as his own notions of art, he may be pardoned for introducing a spot to which he must naturally feel so attached; and though to others it may be void of interest or any associations, to him it is fraught with every endearing recollection.’ Constable feels able to use the familiar to illustrate (actual) landscape coexisting with feeling and ‘Art’.

Fig.3

David Lucas after John Constable

Frontispiece: East Bergholt, Suffolk, from English Landscape 1830–2

Mezzotint on paper

Image: 139 × 187 mm

Tate

Critics such as Ray Lambert have discussed Constable’s familiarity with Alison’s writings,16 but the emphasis to date has been on how Constable used them and those of Sir Joshua Reynolds while forming his own thoughts about a specifically English landscape art, which should be appreciated on a par with history and portrait painting, two genres that were traditionally considered superior. Art historian Iris Wien further suggests that Constable was attracted to Alison’s moral and religious messages, observing that ‘Alison’s assertion that “the appearances of the material world” were clearly expressive of God’s providence was one that the deeply religious Constable fully embraced’.17

In bringing Constable back into a relationship with the wider culture of topographical printmaking we face considerable obstacles. I have written elsewhere of how the distinction between, and resulting perceived chronological progression from, the ‘topographical’ and ‘descriptive’ to the ‘romantic’ or ‘sublime’ within landscape imaging is a false one.18 It has, arguably, distorted our sense of the more complex, multi-faceted and simultaneous forms and varieties of landscape imagery. But the influence of this line of thinking is proving hard to dispel. Art historian Martin Hardie cited Constable as one of the ‘romantics’ who depend ‘not so much on topographical interest as on the sentiments aroused by the painter’s personal interpretation of some aspect of Nature seen or imagined’.19 The ‘failure’ of English Landscape is partly explained by Leslie Parris in light of Constable’s visionary creativity, which Parris argues contrasted with ‘the plainest topographical records’ by more ‘humble practitioners’:

This period saw the emergence of landscape as a leading genre in British art. It was a field that attracted the most creative figures of the age as well as one in which many humble practitioners laboured. The range of work produced was indeed wide: from the plainest topographical records to images that represented landscapes more of the mind than of external realities. Printmaking not only replaced this diversity but, offering additional techniques, increased it. Some artists took the diversity of nature and of their own responses to it as a theme in itself. Through printmaking the landscape artist hoped to reach a wider audience but the more creative were often too far ahead of the public to succeed in this.20

By this logic, paying too much attention to the topographical content of Constable’s work risks appearing to look at the ‘wrong’ things, or in the ‘wrong’ way: a way that would include the uncritically touristic gaze which prevails at Flatford, now a National Trust site, where visitors will look at the landscape and their postcards of Constable paintings, matching and comparing the two. Such a way of looking might appear, from the perspective of academic art history, naïve or uncritical. This separation between two ways of reading Constable’s landscapes is plainly visible in Attfield Brooks and Alistair Smart’s book Constable and His Country (1976), in which a local history perspective is adopted by Brooks, who sets photographic evidence against Constable’s paintings to prove their local specificity, and an art historical perspective is adopted by Smart, who sees Constable transcending locality. The two views sit together rather awkwardly and given the subsequent development of the art history of British landscape painting, with its emphasis on the social and political content of art, the social identity of the artist and the historical reception of his work, the gap between art historical and touristic and topographical interpretations has only widened.

The present essay represents a further effort to test the enduringly potent, but misleading, distinction between topography and landscape. In doing so, it joins with several other efforts to revise the history of landscape art over at least the past forty years. The ‘new’ art history of landscape painting that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s led to a degree of scepticism about the reliability or legibility of these images as records of place, and rather saw the art as embodying social and political perspectives.21 It was in those regards exemplary of the kind of suspicious readings critiqued by Felski, where the work of art is seen as symptomatic of wider social structure. Scholars have more recently been invited to return to the topographical content.22 To date, this has had little impact on Constable studies, as interpretations of the English Landscape series have been dominated by efforts to relate Constable’s art to national and class identities in Britain.23 Constable’s enterprise has thus been folded more critically back into a larger cultural narrative about emerging English or British national identity, thereby severing it from its topographical context, which Constable drew attention to in his advertisement for the series: ‘The subjects, consisting mostly of home scenery, are taken from real places; and are meant particularly to characterise the scenery of England. In their selection a partiality has been given to those of a particular neighbourhood, but some of them may be more generally interesting as the scenes of many of the marked historical events of our middle ages.’24

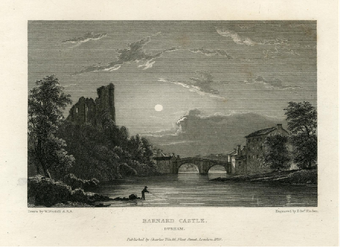

Fig.4

William Westall

Barnard Castle, Durham from The Landscape Album; or Great Britain Illustrated 1833

Etching and engraving

142 (cut) x 222 mm

British Museum, London

The edition of the Literary Gazette that featured this advertisement also carried reviews of William Westall’s The Landscape Album; or Great Britain Illustrated of 1833 (fig.4) (‘the numerous views are various and locally interesting – such as the artist would choose for subjects, and the antiquary or topographer for descriptions’)25 and of landscapes shown at the winter exhibition of the Society of British Artists in London (‘When winter shall have spread its mantle of snow or fog over the face of nature, and the country and its prospects shall be hid from our sight, their semblance will glow on the walls of this gallery, and their future re-enjoyment be anticipated through the perspective of the imagination’). It has been assumed the advertisement’s aim was to increase and widen English Landscape’s circulation. Whether or not this is correct, the Literary Gazette appears to show artists, antiquaries and topographers, plate-books and paintings apparently coexisting and working towards similar goals.

Our understanding of the scope and character of topographical image-making in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries has been transformed over the past few years thanks to pioneering work by, among others, Stephen Daniels and John Barrell.26 While the opposition of ‘landscape’ to ‘mere topography’, of ‘art’ to ‘documentation’, that undoubtedly emerged during Constable’s lifetime remains intrinsic to art historical discourse around picturing landscape, images that have been marginalised or dismissed as simply descriptive or as a foil to ‘high art’ have been recovered as commercially vigorous and culturally revealing. Constable’s English Landscape is therefore ripe for reassessment in light of this thinking.

Presenting English Landscape: Publishers, museums and libraries

Fundamental to how English Landscape might be located in relation to the apparent poles of ‘landscape’ and ‘topography’, and ‘art’ or ‘commerce’ – and judged, in either regard, as a ‘success’ or a ‘failure’ – is the simple, material question of format. As will be shown below, the print series had a fluid identity in Constable’s lifetime and crucially since, morphing into a book-like publication and being promoted as scarce and steeped in meaning. Despite the wealth of scholarship and surviving correspondence, it is difficult to gain a full sense of the motives behind the English Landscape series without being influenced by how it has been presented and promoted after Constable’s death.

A ‘print room mentality’ has arguably complicated matters. By this I mean that the prints are collected and catalogued in public and private print rooms worldwide as outstanding examples of mezzotint and of landscape, but their original means of presentation and their accompanying text are largely seen as irrelevant, or rather rendered invisible by the standard principles of cataloguing. Individual plates may be fully documented, but the varying original wrappers, covers or boards appear not to be given the same scrutiny. Accordingly, English Landscape is probably most familiar today as individual plates in mounts, either stored in boxes or framed for gallery display. Full or near-complete sets preserved in this manner are held by, for instance, the British Museum, Tate and the Victoria and Albert Museum, from among just the UK national museums. Where these have also been published online, presenting frontal digital images of single sheets can only exacerbate the issue.27 Where illustrated in secondary literature, English Landscape is generally shown as single plates along with apparently related paintings or watercolours; when exhibited, given differing environmental requirements, it is usually seen displayed with archival material, at one remove from Constable’s oil paintings and used to illustrate his life as much as, or more than, his art.

Further confusion is caused by library (‘book’) cataloguing, which suggests a false uniformity to works with the same title page, regardless of the differences between individual plates. Constable issued his mezzotints in five parts from June 1830 to July 1832, the first four numbers containing four prints each and the fifth containing six prints, making twenty-two prints in total. Issuing plates grouped in paper wrappers was an established form of presenting topographical and other imagery, but wrappers were cheap and flimsy and were most often replaced with a more durable alternative or discarded. Plates could be bound to create distinct, book-like entities when title pages and text were issued by the artist or publisher; separated and used to illustrate alternative publications; or kept as sheets in print rooms, albums or portfolios,28 such that the owners of the prints had considerable say over how the works were presented.

Fig.5

Nathaniel George Philips

Title page of Views in Lancashire and Cheshire of Old Halls and Castles; Intended as Illustrations to the County Histories 1822–4

Etching

275 x 212 millimetres (platemark)

British Museum, London

Standard bibliographic cataloguing obscures these fluid boundaries between prints and books and the multiple ways in which prints could be issued, collected and used with and without text. This is illustrated by another self-published ‘topographical’ publication by Constable’s contemporary, the painter Nathaniel George Philips. His Views in Lancashire and Cheshire of Old Halls and Castles; Intended as illustrations to the County Histories 1822–4 (fig.5) is rare as an ‘intact’ book but its title demonstrates it was not originally intended to be bound and used as such, but was more ephemeral: the plates were issued without accompanying text and intended to be collected as needed to be inserted into other books, to provide extra illustration to their texts.

As mentioned, the ‘book’ format and its bibliographic cataloguing gives a false uniformity to works such as this, with each copy forming just one possible manifestation of these prints.29 Philips also published them in two sizes: forty-four sets of the folio (large) edition were sold as lot 157 of the posthumous sale of his collections at Messrs T. Winstanley and Son, Liverpool, on 10 October 1831, and a further forty sets were sold as lot 158, with four quarto (smaller). The plates are dated 1822–4, and are not bound in chronological order in the copy held in the British Library, which has a title page but no date. It has one wrapper from ‘No.6’ bound into it that lists the contents of this part – four plates – and shows that they are now bound in a different order. Like Constable’s, this work was also re-issued later in the nineteenth century.30

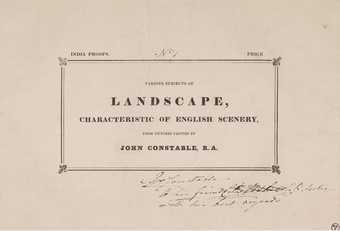

Constable issued a title page for English Landscape in 1830, apparently before any other form of letterpress had been envisaged for the project. It appears suitable for a set of artists’ prints, reading ‘VARIOUS SUBJECTS OF / LANDSCAPE / CHARACTERISTIC OF ENGLISH SCENERY / FROM PICTURES PAINTED BY / JOHN CONSTABLE, R.A. / ENGRAVED BY / DAVID LUCAS.’ He included an introduction dated 28 May 1832 in the July 1832 instalment, and prospectuses for this edition used a similar text to the introduction.31 By June 1832 Constable was referring to an ‘Appendix’, and in October that year six plates were discussed as forming material for a sixth part, but these plans came to nothing.32 In late 1832 Lucas and Constable were working on coloured plates – an alternative version of the edition, which also never materialised.33 Constable issued a second edition of English Landscape with Colnaghi in May 1833, cheaper than the 1830–2 edition, and containing mostly the same prints as the first but in a different order, and with a revised title page and letterpress to accompany some plates. The title page reads: ‘VARIOUS SUBJECTS OF / LANDSCAPE / CHARACTERISTIC OF ENGLISH SCENERY / PRINCIPALLY INTENDED TO MARK / THE PHENOMENA OF THE CHIR’OSCURO OF NATURE: FROM PICTURES PAINTED BY / JOHN CONSTABLE, R.A. / ENGRAVED BY / DAVID LUCAS’.

These changes do not necessarily reflect the project’s reception or Constable’s mental state, as has often been suggested. Topographical print projects tended to grow in a somewhat haphazard manner, and even when advertisements confidently outline their full scope, they were often altered or cancelled. Constable’s contemporary Samuel Egerton Brydges noted how a book issued in parts can have what he calls a ‘temporary arrangement’, subject to change if a project proves successful enough to continue. He writes in his Topographical Miscellanies of 1792,

Of this Work the seven Numbers now published will form a tolerable Volume, by such a temporary arrangement, as the present materials require. If the whole should ever be completed, which must depend among other things on the opinion the public shall form of it, (for nobody would be so foolish as to continue the great expense, at which it must be carried on, without any chance of being nearly repaid,) the addition of immense quantities of new Articles must totally alter the order. Such was the case with GROSE’s excellent collection of Castles and Abbies, a Work which has gradually embraced, almost completely, such objects throughout the Kingdom. But when one recollects the number of years he was employed in bringing the England only to a conclusion, even from 1771 to 1787, the heart sickens at the improbability of equal opportunity, equal resolution, or equal success: not only grief, illness, and death, but even satiety, indolence, and a love of change may stop one’s course: even now I feel my ardour subside, a love of ease is creeping upon me, and I regret the loss of time, that is wasted in these dry and thankless pursuits.34

We often lose a sense of the production history of a work when wrappers have been discarded as works were bound. Advertisements can also reveal ambitions which came to nothing, changes of plan and the variety of ways in which works were originally presented. Looking at prints’ publication dates can often show how projects that have ended up having a seemingly straightforward identity when bound as a book were in fact published in parts, in non-chronological order, or with other ‘books’ more or less distantly in mind as a final product. One pertinent example is Joseph Wilkinson’s Select Views in Cumberland, Westmoreland and Lancashire (1810), a copy of which Constable owned: this was issued in twelve parts, but bound copies often bear no trace of this.35

Fig.6

George Walker

North View of Roslin Castle, from Select Views in Scotland, Including the Seats of the Nobility and Gentry, with Topographical and Historical Descriptions 1793

Aquatint and etching

Image: 303 x 399 mm

British Library, London

A further example would be George Walker’s Select Views in Scotland, Including the Seats of the Nobility and Gentry, with Topographical and Historical Descriptions (fig.6). Bibliographic sources suggest that only the first number of Walker’s projected book from 1793 was ever printed, and that even this only survives in two copies, one held at the British Library and one at the National Library of Scotland.36 Walker has not enjoyed the same level of fame as Constable but he was not unknown in their day. His appointment as ‘Landscape painter in crayons to his majesty’ King George III was announced in September 1806.37 Like Constable, Walker self-published, but one might assume his ‘book’ would be secure as he is able to cite booksellers in London, Edinburgh, Bath, York, Dublin and Rome, as well as A. Molento, ‘printseller to her Royal Highness the Duchess of York’, and his list of subscribers included individuals from Rome, Moscow, Virginia, Jamaica, New York, St Petersburg, Florence, Naples and India, and eleven libraries including His Majesty’s Library, the Vatican, and the Universities of Glasgow, Edinburgh, St Andrews and Aberdeen. The unfinished work’s current lack of visibility in these collections suggests that the unexpectedly short print run and resulting unwieldy, flimsy format led to most copies losing their original identity. King George III’s copy may be typical in having survived as plates without the letterpress.38

Walker’s prefatory ‘address’ is very similar to Constable’s for English Landscape. In it he highlights how aquatint captures the essence of drawing and has enabled the production of Cabinet pieces (small pictures for private viewing) which ‘by representing to the mind delightful scenes though distant, and pleasing scenes though past, afford a pleasure, elegant, pure, and lasting’. Those who want to improve at drawing can copy the image and compare it with the real scene, ‘the original in nature’, and ‘if somewhat advanced in the art, they can copy from nature, and compare their own Drawing with the Aquatinta Print of the same scene; still endeavouring to excel’. Finally, Walker is careful to promote himself as a professional:

The love of the Art, and a desire to promote the improvement of his pupils, induced the Publisher [Walker] to think of exhibiting occasionally, as his engagements in the line of his profession would permit, a few of the most Picturesque Views of Scottish Scenery. Among these will be introduced such of the Seats of Nobility and Gentry as are most remarkable, either for the beauty of the landscape around them, or for their own historical celebrity; the whole intended to form a Collection of Scenery the most striking and interesting that this division of British empire is capable of affording.

Walker’s project proved to be abortive. He did not, perhaps, have the material means or inclination to persevere, as Constable was to do.

English Landscape cites Constable as the publisher and Colnaghi, Dominic Colnaghi and Co, Pall Mall East as sellers. It is only with hindsight and access to Constable’s correspondence that we can judge ‘the firm of Colnaghi as not very successful selling agents’.39 On 27 June 1833 Constable famously wrote to David Lucas: ‘Colnaghi has never sent for one copy since my advertisements – nor has any other printseller. The whole work is a dismal blank to me – and a total failure & loss’.40 Letters of 4 July and 11 December 1834 from his Charlotte Street neighbour, the engraver Frederick Lewis, show how the work remained unfinished at that time. Lewis wrote:

It is impossible for me to express to you how much I am delighted with Your Glorious work & how can I thank you enough for this very handsome & kind present – ….This work adds to mind, & gives such pleasure / to it / that every one that possesses it must be a better person, depend on it you will hand your name down to posterity. / I gladly accept this most beautiful present & will be happy to get still deeper into your Debt, by accepting the appendix that you have so kindly promised me.

Lewis went on to say: ‘Your handsome present of your work I am constantly looking over it is a great source of pleasure to me and I long to have them bound up.’41 English Landscape remained a work in progress, with Constable’s promised ‘Appendix’, incomplete at the time of his death in March 1837, published posthumously by Moon in 1838.42

Original and subsequent formats

The quantity of prints put up for sale at Constable’s death is often quoted as evidence that his English Landscape project was overly ambitious. The auction catalogue details a breakdown of the variety impressions of this ‘highly popular work’for sale, quoting 280 sets and enough loose impressions to make up a further 55 sets, and stating ‘the numbers are neatly done up in coloured wrappers, five forming a set’.43 A book would commonly be built up by such ‘numbers’, or issues of wrapped plates. The Art Institute of Chicago owns five such numbers, making a full set, each number bound with blue silk ribbons (fig.7).

Fig.7

David Lucas after John Constable

Cover of English Landscape 1830–2, no.1

305 × 465 mm

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

The steel plates themselves were also offered for sale. The first edition of C.R. Leslie’s biography of Constable from 1843 featured the plates, cementing the predominant biographical reading of their meaning, but it seems uncertain whether publisher James Carpenter used leftover originals or needed to re-issue them.44 Carpenter’s own advertisements, published in 1842 and 1843, seem to suggest that he had re-issued the plates but had limited the print run to 150: ‘As the number of copies printed will be limited to One Hundred and Fifty, the Impressions of the Engravings, which are on Steel, will be equal to proofs, and the price of the work, to Subscribers, will be Two Guineas and a Half in boards.’45 Yet a review in the Athenaeum, Journal of Literature, Science and the Fine Arts from February 1844 states that ‘The prints are the actual impressions taken during Constable’s lifetime, and the plates of them having lain in a cellar unattended to have become corroded and spoiled, so that there can be no re-issue of the work.’46

As Constable himself oversaw them, the prints were produced on large paper (310 x 490 mm) and in a landscape format, a lavish and flexible production that defies typical shelving and would demand attention whether bound, viewed in a portfolio, or framed.47 Later editions have somewhat diminished this physical presence. Henry Bohn’s 1855 edition is portrait in format and reduced to 425 x 285 mm. Bohn’s introduction stresses their scarcity: ‘Of the engravings forming the present collection, twenty-two were published by himself, and have long been scarce; five more were engraved while he lived, but withheld from publication; and the remaining thirty-three have been engraved since his death, and are now for the first time offered to the lovers of Art.’ Bohn was attempting to market Leslie’s biography at the same time, and makes the link between the two explicit, providing quotations and page numbers for further reading for most plates.

Fig.8

David Lucas after John Constable

Frontispiece: Various Subjects of Landscape, Characteristic of English Scenery from Pictures Painted by John Constable, R.A. 1830–2, with a dedication to the painter C.R. Leslie

Sheet: 197 x 289 mm

National Galleries Scotland, Edinburgh

Within a period of less than twenty-five years, English Landscape might reasonably have been considered at different points as a small issue of individual prints, a series, a series intended for binding with letterpress, and something edging much closer to book illustration. Even within Constable’s lifetime the prints were presented in a wide variety of formats, on three types of paper support, and Constable often ‘touched’ copies as he presented them to emphasise their individuality. He sold them or presented them as gifts both with and without letterpress, as single sheets, as small parts, or as a compilation to be bound as a book in future (fig.8). Perhaps what had begun as a set of prints, and was warmly received by Constable’s friends and professionals, morphed into a book due to this warm reception. In the Literary Gazette advertisement Constable is thankful for ladies who collect prints for their albums and refers both to ‘sets’ and to a ‘book’, and to himself as ‘Author’.48 He reveals how the project is still taking shape as he and Lucas are putting the series together in a letter to the writer, bookseller and bibliographer John Martin of 26 November 1830: ‘I was desirous of procuring the drawing which I made you of Warwick, which you say Mr. Finden is unable to engrave ... Mr. Lucas will put it in hand for my book – as it happens it is just the subject we want in the 5th number. I contrive if possible to get an heroic subject into each, and we are rather deficient in English castles.’49 He issued his plates in small groups, which was normal practice, and gave away most of them. He writes to book- and print seller William Hookham Carpenter on 15 February 1830: ‘I send you a few Proofs – as a mark of my esteem. They have not yet seen the light,’ and seems to have felt encouraged enough by their reception to re-issue the plates with letterpress – surely a sign of success rather than failure if we judge the prints according to what most similar ventures aimed to do.

If there were ambiguities at this time about the format in which prints were presented and the ways in which they circulated, and the ‘temporary arrangement’ of print publications generally, these issues seem acute in relation to English Landscape given the cultural status of its author and how he has been embroiled in notions of Romantic artistic autonomy.50 Constable is an exemplar of the kind of creative independence and authenticity powerfully associated with Romanticism.51 Art historians focusing on these prints have tended to disassociate them from Constable’s words: Frederick Wedmore, in his Constable: Lucas: With a Descriptive Catalogue of the Prints They Did Between Them (1904), makes no mention of accompanying text, attending instead to the interests of his intended audience of print collectors by detailing changes in lettering through proofs and editions of the prints as single sheets. Andrew Shirley, in The Published Mezzotints of David Lucas after John Constable, R.A.: A Catalogue and Historical Account (1930), arguably addresses the same audience, but does at least include Constable’s ‘title pages and introductions’ as an appendix. More recently, Andrew Wilton, in Constable’s ‘English Landscape Scenery’ (1979), has tried to capture the essence of the publication, but he effectively projects some kind of ideal version of English Landscape that never actually existed. He reproduces the order of plates from a British Museum copy of the 1830–2 edition, but ‘Where Constable composed letterpress from the 1833 edition, one of his many versions [of the texts] is reprinted with the relevant plate’ and ‘Where superior impressions of published plates exist in the [British] Museum’s collections … these have been used in preference to those from the bound set.’ Wilton also notes that ‘Where possible, the symbol denoting the “class” of landscape represented by each subject, as it was assigned by Constable in his notes, is recorded here; not because it was used in the publication, or indeed rigidly adhered to by the artist, but simply as a point of interest.’ The plates are ‘reproduced at actual size except where indicated’ – this exception is indicated in eighteen out of forty-two cases. Furthermore, ‘Since Constable altered the titles of his plates several times, his alternatives are given when they throw further light on the subject matter.’52 While the volume of evidence available about English Landscape is considerable, and even overwhelming taking into account Constable’s surviving correspondence, this selective approach to recording and presenting material evidence has inevitably had an effect on how the series is perceived.

Interpreting English Landscape

Fig.9

David Lucas after John Constable

Stoke-By-Neyland c.1829, progress proof before letters, for English Landscape 1830–2

Mezzotint with etching and drypoint

179 x 254 mm

British Museum, London

Modern commentators on English Landscape have wished to see it as reflecting Constable’s profound personal interests, and have been uncomfortable with the relationship between the prints and the accompanying texts. The dark mezzotints have come to be associated with themes of death, desperation and ultimately futility that never really surface in the textual materials (fig.9). Scholar Ronald Paulson, for example, writes of the significance of their timing: ‘It should also be noticed that the project followed closely upon the death of [Constable’s wife] Maria [Bicknell] in 1828 and [his] … election as a Royal Academician in 1829. He must have felt this to be his final effort to vindicate himself as an artist and to make his point about specifically English landscape.’53 However, if one looks at how Constable himself described the project, a different story emerges. His correspondence from this time reflects a wave of wild enthusiasm for the project, a dark period in which he writes very strongly worded letters to David Lucas at very close intervals, followed by an upsurge in positivity again, with plans emerging for how to continue, expand and diversify the project. Despite the evidence, English Landscape has been placed firmly at the far end of the established scale of value that distinguishes descriptive ‘topography’ from relatively autonomous and emotive ‘art’.

The letterpress has been seen as demonstrating Constable’s poor abilities as a writer, with his many versions revealing his desire and failure to perfect his message.54 But working as part of a team and gathering snippets of information and quotations from various sources was normal practice in the context of topographical writing. Constable had access to a wide range of texts and knowledge, with a large library and print collection,55 and his correspondence provides evidence that he was part of a network that actively exchanged information. For instance, Constable wrote in November 1835 to a Mr Smith of 72 Great Portland Street (apparently Frederick L. Smith, Esq., a chemist, based on contemporary directories), returning loose prints and text:

Accept I beg my best thanks for the loan of these interesting things – they provide a most valuable mine to me, including full a Century & a half of the Progress of Landscape. / I hope we shall now meet a little oftener – I hope You will find all complete as I received them – they have ‘till now not been rolled but kept in a large portfolio – the lesser ones I have retained as believing them to belong to Mr Westall I think Yours were all of a size. 42 & a letter press.56

A review of English Landscape in the Athenaeum from June 1830 uses similar language to the introduction that Constable would write two years later, and promotes the series as demonstrating Constable’s accurate rendition of nature and the local, rather than his having transcended such concerns:

This little work will be published in about a week or ten days, and we have been gratified with the sight of the four plates of which the first number will consist. The subjects are more varied than we could have expected to find in a work taken wholly from the productions of Mr Constable; who appears to have fed his genius, like a tethered horse, within a small circle in the homestead …

The painter’s object, which has evidently been to give the varied effects of chiaroscuro, has been well seconded by the engraver … To the admirer – but that is a cold word – to the lover of nature, these, which are faithful miniatures of his mistress, will be treasures indeed …

Constable has been unjustly accused of being a mannerist: Alas! How may a man of genius be condemned outright, or ‘damned with faint praise’ by critics who never saw an honest ‘bit of nature’ in their lives. The mannerism lies at the door of nature, if mannerism there be. Living by, or within sight of, or in the mill (what matters where Genius condescends first to alight), Constable has watched and felt all of the intricacies – all the sense, the solitude, the simplicity, the beauty of mill scenery; - and, heart in hand, he has dedicated himself to his native field, tree and water – knowing and feeling that in nature’s plainest mood, there is a soul of beauty.57

The edition being reviewed was published with a title page only, but given Constable’s interest and active involvement in the press, it is possible he would have kept hold of a favourable review, and this may have influenced the writing of his own introduction. Art historian Adele M. Holcomb has written of Constable contributing to the Athenaeum himself on at least two occasions, and she notes that the review quoted above was written by the poet and journalist John Hamilton Reynolds: ‘Reynolds’s observations are so close to Constable’s own claims for his art as to suggest that they might have derived from discussions with the artist.’58

Some of Constable’s borrowings are more overt. As noted above, Constable began the East Bergholt letterpress with the request that ‘he may be pardoned for introducing a spot to which he must naturally feel so much attached’ since ‘to him it is fraught with every endearing recollection’. Yet while he focuses on the personal meaning of this area that was his childhood home, Constable also promotes study of the East Bergholt plate as an artistic work by drawing attention to his use of light and shadow to convey the time of day and even ‘pathos and effect’. Furthermore, in giving the history of East Bergholt, he quotes a popular topographical publication – Frederic Shoberl’s The Beauties of England and Wales; or, Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Descriptive, of Each County (1813):

East Bergholt, or as its Saxon derivation implies, ‘Wooded Hill’, is thus mentioned in ‘The Beauties of England and Wales’: ‘South of the church is the “Old Hall”, the Manor House, the seat of Peter Godfrey, esq., which, with the residences of the rector, the Reverend Dr Rhudde, Mrs Roberts, and Golding Constable, Esq., give this place an appearance far superior to that of most villages.59

His selective quotation of Shoberl’s text should be seen in the context of other topographical publications, where quoting, repurposing and disputing text is a common occurrence. For instance, the description of East Bergholt in The Beauties in England and Wales is itself an updated version of John Kirby’s in The Suffolk Traveller (1764).60 Constable’s English Landscape can therefore be situated in a larger, cross-generational topographical enterprise of information gathering, updating, personalising and improving.

Status and exchange

Locating English Landscape securely within the established schema opposing landscape to topography, the amateur to the professional, and the commercially interested to the aesthetically disinterested is bound to be frustrated by the evidence. To force the enterprise into these schematic oppositions is to misrepresent the project. Antony Griffiths has observed that ‘the primary motivation of artists to have prints made was not financial’,61 stating further that ‘The concern for reputation rather than profit was accepted by all parties concerned and underlay the thinking of the period.’62 We can therefore see a work such as English Landscape as part of a system of exchange with the aim not of immediate financial gain but of building one’s status.

In October 1833 Constable wrote: ‘My book is esteemed by my professional friends – more perhaps than by the world – which I indeed anticipated – but why should artists – and others in their publications – climb downwards – and be so ready to follow – instead of lead, the taste of the publick.’63 What is at stake in this account is not the right to self-expression routinely projected onto the Romantic artist, nor outright commercial imperatives, but the part that English Landscape might play in establishing a dignified role and social place for its author. Considered in the context of Constable’s unstable status as an artist – which wavered between amateur and professional, as we would understand these terms – the project might more properly be seen to reveal a degree of equivocation on Constable’s part with regard to commerce and disinterest. And crucially, when considered as topography – in the enlarged and more dynamic sense argued for by more recent scholarship – the project could equally address commercial, self-promotional, aesthetic and patriotic concerns.

Set amid the context of contemporary topographical print publishing, Constable’s English Landscape may not look so entirely atypical as is often assumed. It did not immediately make money for the artist, but it is not clearly the case that such publishing projects were generally expected to do so, or that they always intended to make profits in the manner we might assume. Even the most personal aspects of the plates, highlighted by Constable’s own commentary, do not remove them as much as is often assumed from the norms of landscape print publishing, even of the most strictly topographical kind. There are presently no straightforward answers on these points, but the normative perspective taken on the prints in English Landscape – that they are manifestations of the artist’s imaginative will, and are removed from prevailing commercial motives and topographical publishing methods – may only make attending to these questions all the more difficult.