Introduction

Richard Demarco is without doubt a remarkable man, an Italian Scot, a founder of the Traverse Theatre, a man who is an artist, a writer, a philosopher. He is a man who brought contemporary visual arts to the Edinburgh Festival. He has been involved in more than 50 Edinburgh festivals, and he brought great artists like Joseph Beuys and [Tadeusz] Kantor to thousands of people. He has also brought the visual arts from other parts of the world, from Eastern Europe, long before other people were interested. And he’s inspired us all, he’s inspired us to take extraordinary journeys in the mind, journeys across Europe, journeys that he calls the road to Meikle Seggie.1

Sir Nicholas Serota

Director, Tate, 2007

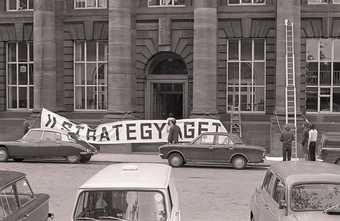

Fig.1

Entrance to the Edinburgh College of Art with the banner for Strategy: Get Arts

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

The exhibition Strategy: Get Arts (SGA) (fig.1), organised by the Scottish artist, gallerist and impresario Richard Demarco in collaboration with the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, was held at the Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) between 24 August and 12 September 1970. It represented a new generation of artists from the ‘Düsseldorf school’, artists distinct from their predecessors in the various pre-war circles of Expressionism and Dada. Nevertheless, there were certain continuities, especially stemming from the live performance art strategies of Dada. That legacy could already be identified earlier in the 1960s, in the events of the international Festum Fluxorum Fluxus, involving the likes of Nam June Paik, George Brecht and George Maciunas, and held at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in February 1963. This is where Joseph Beuys famously performed his ‘action’ Siberian Symphony, First Movement (Sibirische Symphonie, 1. Satz).

Aside from the very international Fluxus network, another rather more ‘German’ circle of artists would emerge during the period known as the ‘Wirtschaftswunder’ (or ‘Miracle on the Rhine’) in peacetime West Germany in the decades following the Second World War. These Düsseldorf-based artists, including Sigmar Polke, Blinky Palermo, Günter Uecker, and Gerhard Richter, were also ‘Grenzgänger’ (‘border-crossers’) from Communist East Germany. All desired artistic and societal freedom and experimentation, motivated by earlier memories of a lack of such freedom under National Socialism, or by more recent negative experiences of the repressive apparatus of the Soviet Bloc. By contrast, the wealth of a neo-liberal and democratic Düsseldorf, which in the 1960s was the richest territory of the Federal Republic, provided the conditions for their desired experimentation, even if the often conspicuous consumerism of those who lived in North Rhine-Westphalia was critiqued by some of those same artists who had escaped East Germany, particularly through the ironic ‘Capitalist Realism’ of Richter and Polke.

Parodying the rapid ascendance and accompanying art market for American Pop Art, as well as the propagandist intent of Socialist Realism in East Germany, Capitalist Realism was a self-reflexive ‘movement’ that first achieved critical and public awareness through Richter and Konrad Lueg’s now legendary happening Living with Pop – A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism 1963, staged at the Düsseldorf furniture store, Möbelhaus Berges. The ‘movement’ also questioned the correlation between happiness and mass consumption promised by West German post-war politicians such as Ludwig Erhard, the Minister of Economic Affairs from 1949 to 1963. Although they wryly interrogated consumer culture through their paintings, happenings, and installations, it is undoubtedly true that Richter and Polke benefited from this new societal prosperity and a liberal climate that enabled diverse art practices to emerge, certainly compared with what was possible in their doctrinaire former homeland of East Germany. Furthermore, as the critic Georg Jappe stated in the SGA catalogue: ‘In the open-minded tolerant and inquisitive atmosphere of the Rhine, there were collectors who were able to identify their newly built home with modern art, and, surprisingly enough, often gave some thought to its future development.’2 Well located in proximity to other European cultural centres and with a burgeoning art scene, Düsseldorf drew an international crowd of artists from all over Europe and the United States, as well as more local talent. In the late summer of 1970, many of these artists would find themselves in Edinburgh, at the invitation of Demarco.

The historical context

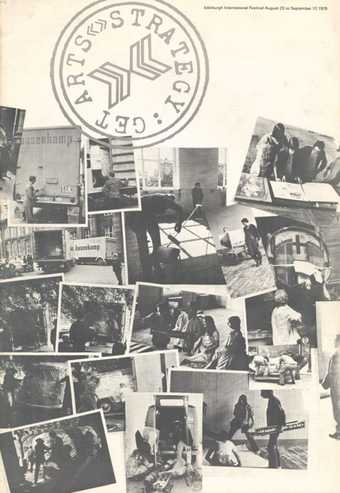

Fig.2

Cover of Strategy: Get Arts, exhibition catalogue, Edinburgh College of Art, 23 August – 12 September 1970

Demarco Digital Archive

In a short preface to the outsize catalogue designed by John Martin that accompanied the SGA exhibition (fig.2), Peter Diamand, Director of the Edinburgh International Festival, wrote in his opening statement: ‘I am pleased that the 1970 Edinburgh Festival has been able to include, as part of its official programme, a major exhibition of Contemporary German art, the first to be shown in Britain since 1938.’3 As will be discussed, this reference to 1938 is then reiterated in a number of press reviews of the exhibition by critics such as Edward Gage (Scotsman), Michael Shepherd (Sunday Telegraph) and Cordelia Oliver (Guardian). On first reading, this point seems rather unlikely, prompting thoughts that there must have been other exhibitions of post-1945 German art staged in the UK after the Second World War and before 1970. The comment does prove, however, to be accurate when bearing in mind Diamand’s words ‘major’ and ‘contemporary’.

Between 1945 and 1970, alongside various monographic exhibitions, there had been a number of larger exhibitions of modern German art staged in the UK, one of the largest being the historical survey exhibition entitled A Hundred Years of German Painting, held at the Tate Gallery in 1956. This was followed in 1964 by another notable Tate exhibition, Painters of the Brücke, on the first Expressionist formation; organised by the Arts Council of Great Britain, it was presented with the support of two of the surviving members of the group, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. The critic Nigel Gosling, writing an Observer review of the 1964 exhibition, did suggest that this Brücke art was still ‘strange and disturbingly unfamiliar’, but by the late 1950s and early 1960s, these Expressionist artists were understood as belonging to the ‘historical avant-garde’ of the early twentieth century and could hardly be appreciated as ‘contemporary’.4 Gosling was also responsible for an enthusiastic review of SGA six years later, which in tenor and title, ‘Unique Gothic rites’, echoed some of the sentiments he expressed earlier about the Brücke, especially with respect to reiterating the cultural trope of the Germanic ‘Gothic’:

I came away from the Edinburgh festival this year feeling that it had given me a unique art experience … In the College of Art is a group show by 35 living artists from Düsseldorf. It is titled Strategy-Get Arts (a clumsy palindrome) and I shall be surprised if it does not prove to be a landmark … The prevailing wind of taste is moving towards the Gothic Quarter … Heartfield’s searing posters and some biting graphics by Max Beckmann. Now the Düsseldorfers add the clinching evidence … It seems to be distantly related to the work of earlier artists like Wols and Schwitters and to past movements like Dadaism.5

Diamand’s brief reference to 1938 in the SGA catalogue, which goes unexplained, does not relate to the Dadaism mentioned above by Gosling, but rather Expressionism, and specifically the 1938 exhibition Twentieth-Century German Art at the New Burlington Galleries, London, which also travelled in a smaller iteration to the McLellan Galleries in Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow, in 1939. In many ways, the exhibition was a riposte to the infamous Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition that had opened in Munich in 1937 and gone on to tour twelve other German and Austrian cities, closing in 1941. Twentieth-Century German Art featured many works by prominent Expressionist artists, such as Oskar Kokoschka’s ironically titled Self-Portrait of a Degenerate Artist 1937, now in the collection of National Galleries Scotland. There was another Scottish connection here too – one of the organisers of Twentieth-Century German Art was the art historian, poet, critic and philosopher Herbert Read, who had been the Watson Gordon Professor of Fine Art at Edinburgh University between 1931 and 1933. During his time at the university, he had published The Meaning of Art (1931) and Art Now (1933). The latter was dedicated to his friend Max Sauerlandt, the Director of the Hamburg Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, who was dismissed from his post in April 1933 by the Nazis. Read’s anger at the National Socialist cultural policy of ‘purging’ art museums seeped into the 1938 catalogue introduction: ‘just when the moment seemed propitious for a more active interchange of ideas, German art was swept away in the country of its origin, condemned on political grounds and ruthlessly suppressed’.6 Read also wrote the introduction to the subversive Pelican paperback Modern German Art (1938), authored by Peter Thoene, a pseudonym for the Yugoslav émigré art critic, Oto Bihalji-Merin, born to a Jewish family in Belgrade. Bihalji-Merin lived in Berlin during the Weimar era, and would later witness the Nazi persecution of modernist artists in Germany in the 1930s, penning the first history of modern German art in defiance of the Nazi regime. The paperback was intended to complement the exhibition Modern German Art at the New Burlington Galleries and its catalogue.7 In his introduction Read also sought to encourage a positive reception of modern German art in Britain, and, as the art historian Shulamith Behr has observed, to prepare a British milieu ‘more attuned to the Paris art world – for a shift in critical standards’.8

Over thirty years later, with SGA, the public would encounter another shift in critical standards related to an exhibition of primarily German artists. Herbert Read died in 1968, two years before SGA, but the connection to the 1938–9 exhibition that ran in counter to the ‘Degenerate Art’ show remains intriguing. An article by the Guardian arts correspondent, Cordelia Oliver, entitled ‘Dada for the seventies’ is notable:

Once, as a schoolgirl in Glasgow I saw an exhibition which because it stunned me into recognising that a proper response to art might be visceral (not merely cerebral as I suppose I had been brought up to believe) began a process of awareness which I have struggled to maintain ever since. That exhibition was ‘Entartete Kunst’ (‘Degenerate Art’) [‘Twentieth-Century German Art’] and contained work by most of the great German Expressionists, proscribed by the Nazis, names familiar now but not then. It has taken 30 years for another comparable exhibition of contemporary German art to reach Britain, and unless I am much mistaken, this one too will have its effect on those who are fortunate enough to experience it.9

Fig.3

George Oliver photographing the arrival of artworks for the Strategy: Get Arts exhibition at the Edinburgh College of Art, 23 August – 12 September 1970

Photo © Richard Demarco

Demarco Digital Archive

In contributions to the Guardian, Cordelia Oliver provided critical coverage of SGA and a profile of Demarco, while her husband George Oliver, a photographer hired by the Richard Demarco Gallery, also played a key role in providing extensive photo-documentation of the exhibition (fig.3). His photographs appeared on the distinctive cover of the SGA catalogue. Along with Demarco’s own photographs and those of the artist Monika Baumgartl, they provide an important visual record of the various installations and performances that took place. The connection Oliver made between SGA and the 1938–9 London-Glasgow exhibition was also picked up by Georg Jappe, who contributed an article to the respected German broadsheet the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. The title of this article translates as ‘More Impact than the Venice Biennale. The British Press Reaction to Düsseldorf in Edinburgh’.10 This surveyed in some considerable detail the critical reception of SGA, thereby alerting a German public to its importance. As mentioned above, Jappe had written for the SGA catalogue and had met and corresponded with Demarco regarding the organisation of the exhibition, so this review would have lacked critical objectivity, but was nonetheless neutral in tone, simply reporting on the show’s British reception. In the winter of 1970, a similar anthology of reaction from the press, as well as Demarco’s own reflections on SGA, appeared in the second issue of Pages: International Magazine of the Arts, a neo-avant-garde artist magazine edited by David Briers.11

Fig.4

Daniel Spoerri’s Banana Trap Dinner 1970, in the boardroom of Edinburgh College of Art for the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

Oliver’s reference to ‘Dada for the seventies’ in her Guardian article is interesting, not least because documents in the archive of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (SNGMA) reveal that even up until July 1970, one title in circulation for the exhibition – and cited in some press reviews – was Art and Anti-Art. This was of course the subtitle given to the first-hand account of the Dada movement by the artist Hans Richter, translated and published in English in 1965.12 The fact that this title was considered clearly signals some expectation that these artists represented Dada’s legacy. Jennifer Gough-Cooper, the administrator of the Richard Demarco Gallery, also used this title in a letter to the Fluxus artist Daniel Spoerri, dated 15 June 1970, thanking him for offering a ‘Gala Dinner’ for invited guests in the ECA boardroom as part of the exhibition. What Spoerri was offering was an experimental meal in line with his ‘Eat Art’ project, the so-called Banana Trap Dinner (fig.4). The menu travesti (‘disguised menus’) were limited edition (signed and dated) artworks by Spoerri. The artist intended a mismatch between the senses of sight and taste, with dishes such as mashed potato resembling ice cream and garnished with a salty biscuit, or a marzipan sausage for dessert; the dinner was served by candlelight to further confound the senses. The whole prospect slightly concerned the pragmatic Gough-Cooper, who wrote: ‘We like the idea of some experiments, but I think that people may be quite hungry!’13 Spoerri would go on to open his Eat-Art-Gallery in Düsseldorf on 18 September 1970, not long after the dinner at ECA.

SGA was a ground-breaking exhibition in that it brought not just Spoerri, but many important contemporary artists to the UK for the first time. Most were unfamiliar to the British public at the time of the exhibition, but would later become appreciated as key figures, including a roll call of German artists who would attain international significance. These included Richter, Sigmar Polke, Blinky Palermo, Günther Uecker, Heinz Mack, Bernd and Hilla Becher, and of course Joseph Beuys, who at this point had the strongest reputation of the group. What they and others from Düsseldorf brought to the Edinburgh art world proved to be a sensation. These artists generated a dynamic and creative disturbance in a city where the influence of the pre-war Scottish Colourists such as Frances Cadell, John Duncan Fergusson, Leslie Hunter and Samuel Peploe still held sway. This influence continued among those artist-educators who responded in their own expressive way to that ‘tradition’, especially Robin Philipson, Head of the Drawing and Painting Department at ECA from 1960 to 1982. In terms of art teaching, ECA still acknowledged a traditional separation of artistic disciplines and, Communist propaganda aside, in the 1960s it was probably closer in character to the old ‘Leipzig School’ of East Germany, at least in terms of stressing the virtues of oil painting on canvas, than to the Fluxus experimentation of the West German ‘Düsseldorf art scene’. More progressive teachers at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, like Beuys, who admittedly had also to confront conservative forces in their home institution, could nonetheless be seen as picking up where Bauhaus left off in challenging the separation of artistic disciplines and all forms of institutional and societal hierarchy in an ever-increasing expansion of the very concept of ‘art’.14 In the 1960s, art institutions in Edinburgh could therefore be seen as somewhat retrogressive in comparison to what was taking place in the Rhineland. The creative upheaval imposed upon ECA by the Düsseldorf artists was summed up by Merilyn Smith, who commented on SGA in the following terms:

The academic siting of the exhibition was to prove an ideal arena for challenging established authority. Artists, students, administrators and public all had to make decisions and take sides. The classic art confrontation presented fundamental principles for the expression of opinion and persuasion through art criticism. Initial skirmishes between the German artists and the Scottish establishment ensured that serious attention would be focused on the subsequent conflict of art ideologies.15

Key correspondence concerning Strategy: Get Arts

Fig.5

Reiner Ruthenbeck (third left) with Alexander Hamilton (second left) and unidentified Edinburgh College of Art student assistants during installation of Ruthenbeck’s work for Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

There was a certain fluidity about the title of the exhibition in the first half of 1970. While Art and Anti-Art had clearly been mooted at some point, earlier in the year Demarco wrote a detailed memorandum to Peter Diamand (based on his second visit to Düsseldorf in March 1970) in which he suggested that the exhibition was to be called ‘Dusseldorf in Edinburgh’.16 In this document from 25 March 1970, Demarco describes to Diamand his belief that the exhibition would be unlike any other in which he had been involved, stating that ‘the emphasis would not be on the usual installation of paintings and sculptures within the usual accepted idea of an art gallery’, but rather that the exhibition would be ‘an extension of the accepted role of the visual artist and would consist of films, actions, environments, visual – musical concerts and paintings, sculptures and “objects”’.17 Demarco attempted to convince Diamand (and therefore also the Visual Arts Committee of the Festival Society) of the suitability of ECA’s main building as a venue, at a rent of five pounds per day, including ‘the main sculpture court and the corridors leading from it … a very beautiful exhibition space’.18 He also argued that apart from creating a ‘simple cinema where films would be shown throughout the day’, no major ‘alterations to the interior space’ were necessary, and that the exhibition would be less a logistical problem of transporting large and bulky art objects, as had been the case with Canada 101 in the 1968 festival (also staged at ECA), and more a problem of ‘transporting all the artists’.19 Demarco went on to argue: ‘I would like to create environments which depend on these artists’ reaction to the spaces I would offer them at the art college ... Professor Beuys in fact would create an environment out of what would be his first experiences of Scotland.’20 Demarco relates to Diamand how Uecker, Mack and other artists also wanted to create work in situ. One such artist was Reiner Ruthenbeck, who, along with student assistants, would create a small mountainous pile of crumpled black paper on a studio floor, which he referred to as a ‘highland’ (fig.5). Finally, Demarco declares his Gesamtkunstwerk (‘total artwork’) vision to ‘integrate the work of artists in every art form involving the cinema, music and the theatre’.21 Many of the artists did in fact travel to Edinburgh. Of the thirty-five artists from Düsseldorf involved in SGA, the art critic Michael Shepherd commented that ‘24 of the artists are in Edinburgh to liven things up … I would strongly recommend anyone, particularly art students, who can get there not to miss it.’22

Fig.6

Palindrome text works by André Thomkins, laid out for installation in the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

By early July, it seems that the title of the exhibition was settled. A letter from Gough-Cooper to William Thomley, Artistic Assistant at the Edinburgh International Festival Society, makes this clear: ‘The Exhibition is to be called “Contemporary Art from Dusseldorf”. The main part of the title is a palindrome by André Thomkins, one of the artists taking part in the Exhibition. It makes a rather unusual and dramatic title, don’t you think!’ (fig.6).23 The SGA Demarco Archive at SNGMA contains a very large cache of typed and handwritten letters and memoranda from 1970. Many are from Demarco and Gough-Cooper to the Festival committee members, the Goethe-Institut, the Arts Council of Great Britain, Scottish television, various embassies, the art college authorities in Edinburgh and in Düsseldorf, and to the Düsseldorf gallerist Hete Hünermann. There are also official and personal letters to all the artists involved, as well as many other relevant parties. Earlier that year, one letter from Diamand to Demarco written on 5 February 1970 signalled his concerns about the preparation time: ‘The idea sounds very interesting, but unfortunately I am afraid it is too late for 1970. Why not wait until 1971 when everybody will have the time to prepare it thoroughly?’24 And a letter from Demarco to Peter Bird (Assistant Art Director of the Arts Council of Great Britain) on 13 May 1970 requests a note from the Arts Council to say that there would be interest in showing such an exhibition in London. Demarco states: ‘This letter would help me in my negotiations with the Edinburgh Festival Society to persuade them to make the German Exhibition part of the official programme. Part of the problem is that certain members of the Arts Panel do not know enough about these German artists to feel that the show will do justice to the Festival’.25 He then goes on to state: ‘It would be marvellous if the Exhibition could move to London at the end of the Festival.’26 This intention is also reiterated in a letter of the 15 May 1970 to Hete Hünermann, who supported Demarco in his efforts to show the Düsseldorf-based artists in Edinburgh. Demarco comments: ‘I am hoping to transfer the exhibition to London under the patronage of the Tate or the Arts Council of England’.27 This never occurred, in spite of his best efforts.

In one of his Observer reviews of SGA, Nigel Gosling revealed that the Festival Committee had ‘given the show its official blessing but nothing else’.28 This point is underscored by the existence of a letter from Diamand to Demarco in which Diamond refuses Demarco’s requested sum of 400 pounds to support the exhibition, stating: ‘You know that it has not been easy to obtain my Council’s agreement to include the Düsseldorf Exhibition in the official programme. I succeeded only by giving assurance to my Council that, while I was convinced of the artistic importance of the Exhibition, no additional financial burden would accrue to the Festival.’29 The sum requested by Demarco was to partially support the increased rental of ECA, which had jumped from 200 to 600 pounds. Ultimately the financial support for the exhibition would come from German institutions and private funds raised by Demarco, but aside from the considerable difficulties of securing British funding for SGA, the timeframe was seemingly impossible. After confirmation that ECA was going to be the venue for SGA, as well as confirmation of its inclusion as an official Festival event, Demarco and his small Gallery team only had a few months to organise everything.30 When most major art exhibitions today have a lead-in time of several years, it can certainly be considered an extraordinary feat that Demarco could push this amorphous exhibition into existence within such a small period of time. In spite of Diamand’s serious reservations, the many letter exchanges to all relevant parties reveal Demarco’s determination and relentless energy in making sure it could all happen by the late summer of 1970. This energy was noted during the run of the exhibition when John Gale, writing on SGA for the Observer stated ‘Italian Scots seem to be everywhere at the Edinburgh Festival; and at least 10 of them seem to be called Richard Demarco’.31

Fig.7

Richard Demarco photographing the arrival of transport from Düsseldorf at Edinburgh College of Art, bringing artworks and materials for Strategy: Get Arts, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

In his book Scottish Art since 1960: Historical Reflections and Contemporary Overviews, Craig Richardson comments on the chance element of SGA, the feeling that nobody knew quite what to expect in the immediate build up to the exhibition: ‘In the weeks preceding the display the city was buzzing with rumours as to its content, the unknown quantities a challenging position for the Edinburgh Art College authorities.’32 This is confirmed by the recollections of the artist Alexander Hamilton, who was a student helper for SGA:

There was generally a sense of, first of all, blind panic. What is going to come out of the delivery trucks? And secondly, will there be enough to create an exhibition that is going to have an impact during the Festival? But as a young student, I was twenty at the time, this was all extraordinary. This sense that we were going to put on an international exhibition, it was all going to come out of this truck, and these artists were going to start work with some materials.33 (fig.7)

Beuys’s contribution to SGA

Fig.8

Joseph Beuys on Rannoch Moor, with Loch Ba behind, Scotland, 8 May 1970

Photo © Richard Demarco

Demarco Digital Archive

Between 1970 and 1982 Joseph Beuys made a total of eight visits to Scotland, all at the invitation of Demarco, who first encountered Beuys in action at Documenta 4 in Kassel in 1968. After meeting Beuys personally for the first time in the latter’s Oberkassel studio in the winter of 1969–70, Demarco enticed him to visit Scotland by showing him postcards of the sublime Scottish landscape and Celtic and Pictish standing stones, thereby making a connection to Beuys’s own birthplace, the Celtic enclave of Kleve (Cleves) in the Lower Rhine region of Germany. Demarco arranged Beuys’s first trip to the ‘land of Macbeth’ in early May 1970 in preparation for his contribution to SGA. Demarco and his assistant Sally Holman took Beuys to Loch Linnhe, Loch Awe, Glencoe, and Rannoch Moor (fig.8). Beuys also visited Rannoch Moor for a second time, on the 13 August 1970, when he and his family were taken there in a convoy of three vehicles, accompanied by Demarco, Lesley Benyon, Henry Gough-Cooper, the artist Rory McEwen, the filmmaker Mark Littlewood, and the journalist Michael Pye of the Scotsman.

Fig.9

Cover of Joseph Beuys, exhibition catalogue, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1979

Pye’s feature article on the artist was published in the Scotsman on 22 August 1970. In this piece, Pye discusses the presence of Beuys at the ECA, who, much to the janitors’ displeasure, was ‘taking the place apart’, but he also recounts the journey to Rannoch Moor as captured on cine-camera. Pye explains how Beuys stood at the edge of the Moor ‘holding a great lump of calf’s foot jelly’, which he would sculpt into a symbolic shape and hold aloft towards the sunlight, squeezing it and mimicking the action of a beating heart.34 Pye was sympathetic to Beuys and also commented on, without questioning its veracity, the narrative that in the Second World War, Beuys’s Stuka Bomber was shot down in the mountains, where, he claimed, he was saved by nomadic Tartar tribesmen, who wrapped him in insulating layers of felt and fat to keep him from freezing to death. This oft-repeated narrative, even restated as fact in Beuys’s New York Times obituary,35 was famously called into question as fraudulent myth-making by the art historian Benjamin Buchloh in an Artforum article of 1980.36 But ten years earlier this narrative had convinced Pye and others.

On 18 June 1970, Demarco wrote to Beuys informing him of further media interest in him and the planned exhibition, especially from the Observer, stating ‘they are most interested and excited with the idea that you have discovered Scotland’.37 The tone of the letters between Beuys and Demarco was always one of great affection, with Demarco often signing off ‘With much love’. In an interview with Giles Sutherland, Caroline Tisdall commented on the nature of this relationship as one of ‘a brotherly friendship full of warmth’.38 She further stated: ‘Demarco offered more than the art-world to Beuys. He took him to the landscapes of the Celtic imagination, to nature and to mythologies which inspired Beuys’.39 Tisdall, a London-based art critic for the Guardian got to know Beuys through Demarco, and she became an important chronicler and commentator on the artist. Tisdall was the co-curator and catalogue author for the major New York Guggenheim retrospective Joseph Beuys, staged in 1979 (fig.9). In this catalogue, the ECA SGA exhibition was given nine pages of coverage, photos and text, the latter mostly drawn from Alastair Mackintosh’s article on his experiences of SGA, which appeared in the journal Art and Artists in November 1970.40

Fig.10

Joseph Beuys (right) with unidentified assistants pushing the Volkswagen camper van used in his work The Pack (Das Rudel) 1969 for Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

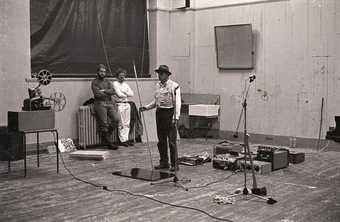

Fig.11

Joseph Beuys and Henning Christiansen performing Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony during the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

Beuys’s contribution to SGA consisted of The Pack (Das Rudel) 1969, Arena 1970, and a performance of Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony (Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottische Symphonie) 1970. Conceived by Beuys the previous year, The Pack consisted of a Volkswagen camper van, children’s sledges, rolls of felt, fat and torches. Of this work Cordelia Oliver wrote: ‘Beuys’s Volkswagen bus spills its load of small immaculate sledges, thrusting and hurtling themselves forward like lemmings to the sea.’41 The Pack evoked the ‘mythic’ Tartar rescue mentioned above, and much more besides. It was a work destined for the large ECA Sculpture Court, but the College authorities refused to allow a vehicle through the main entrance of the building, and so it was sneaked through a side entrance that was used for delivering artistic materials to the Sculpture department (fig.10). Arena consisted of documentation (photographs) of Beuys’s previous projects, while Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony was an ‘action’ inspired by his experiences of Scotland that summer, and in some ways a response to Felix Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture (Fingal’s Cave) of 1830, a Romantic composition Beuys knew well, but found too sentimental.42 Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony was a collaboration between Beuys and the Danish Fluxus composer Henning Christiansen (fig.11), and Beuys’s performance was accompanied by film of Rannoch Moor. Arguably, it was also a collaboration with Demarco, who was responsible for enthusiastically guiding Beuys to these sites in the first place. Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony was to have an impact beyond the confines of ECA when a variation of it was performed by Beuys at the Zivilschutzräume in Basel on 6 April 1971.43

Beuys’s presence at ECA was essential, with many journalists commenting on his magnetism. In an article entitled ‘Convention swept aside by Germans’, the critic Terence Mullaly stated:

At the centre of it all is Joseph Beuys, who invests the trivial gesture, or is it the downright absurd, with the force of his character to the point at which whatever rational judgement may be, respect is commanded. None of the other artists, many of whom are his pupils, almost all his followers, make an equal impact.44

Edward Lucie-Smith, writing for the Sunday Times, noted the impact that Beuys was going to have on arts education in the UK:

Beuys is clearly a great teacher of the young and his doctrine can be summed up in the phrase ‘everything is art’ – except, perhaps, the created object, which is only evidence that action of some kind has taken place. To put it mildly, Beuys is going to create problems in British art schools. He points in precisely the direction which currently most attracts the brightest pupils, and which most dismays the teachers and organisers who have to justify the money spent on art education to the suspicious paymasters of the State. Edinburgh has come up with a great subversive.45

John Gale of the Observer also commented on Demarco’s coup in bringing Beuys to Scotland as well as commenting on the artist’s distinctive appearance:

Beuys, an ex-Stuka pilot who broke every bone in the war, could be a saint; he always wears an old-fashioned grey hat, looks like a haunted skull, is gentle, indifferent to mockery or praise, and stands in some extraordinary way for Germany, the world and the great host of the dead. Demarco is ecstatic about Beuys, and touchingly pleased that he got him to come to Edinburgh.46

Other key artists

Fig.12

A meeting in the studio of Gerhard Richter in Düsseldorf, 29 January 1970, during preparations for the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970. Left to right: Gerhard Richter, Blinky Palermo, Günther Uecker, Richard Demarco facing painting (centre)

Photographer unknown

Demarco Digital Archive

Fig.13

Gerhard Richter

Field Mill (Feldmühle) 1970

Oil on canvas

500 x 600 mm

© 2018 Gerhard Richter

When Demarco visited Düsseldorf in January 1970, where he discovered a major artistic centre with an impressive network of galleries, he met not only Beuys, but also Günther Uecker, Blinky Palermo, Gerhard Richter, and many others. It was in Richter’s studio that Demarco discussed the possibility of SGA and that the success of such an exhibition would depend on the willingness of the artists to travel to Edinburgh and make site-specific work (fig.12).47 Correspondence in the Richard Demarco Archive reveals Richter’s support of the exhibition and a very good relationship between the two of them is evident. In a letter dated 31 July 1970, Demarco thanks Richter for helping him make the exhibition possible, invites him to stay at his home as a ‘personal guest’ and suggests that ‘he attend the opening and also discover the beauty of Edinburgh and the Scottish landscape’.48 In a handwritten letter to Demarco dated 28 August 1970, Richter writes ‘It was a wonderful time for me, with you, in Edinburgh, at the exhibition, in the Highlands, with all the nice people, and also in great London. I thank you, I thank you very much. I love you. Shortly I’ll write you more.’49 And furthermore, in another letter to Demarco written on 1 September 1970, Richter offers him a gift of one of the paintings displayed at the ECA, Field Mill (Feldmühle) 1970 (fig.13), but also asks him to ‘Please be patient with the other plans – Scottish landscapes exhibition etc’.50 Clearly Demarco had ideas to work with Richter again on another project.

Fig.14

Blinky Palermo making his wall painting Blue/Yellow/White/Red in August 1970, for Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

Fig.15

Stefan Wewerka in August 1970 during the making of his installation for Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

Richter had flown to Edinburgh along with Palermo, Imi Knoebel and Gotthard Graubner on 19 August. Palermo wrote to Demarco on 7 August explaining his intention to come one day earlier than he intended ‘because I don’t know exactly what time I need to realise my piece’.51 The piece in question was Blue, Yellow, White, Red, a wall painting comprising a horizontal band of primary colours which ran around the architrave (fig.14), beneath which the broken chairs of Stefan Wewerka lay scattered on the main staircase of ECA (fig.15). This installation was memorably described by Oliver: ‘Wewerka’s deformed chairs struggle drunkenly up the main stairs (or in another mood, like wounded soldiers after a battle).’52 Palermo’s wall ‘intervention’ was later whitewashed by the College authorities.53 Much more problematic for ECA was Graubner’s A Homage to Turner, which was the creation of a mist room in a confined space. This led to a fire, the circumstances of which presaged what occurred decades later at the Glasgow School of Art in 2014. Alexander Hamilton recalled what happened:

We borrowed a smoke making machine from the Lyceum, which in those days involved using paraffin that you lit to create the smoke … Once we got the machine started, it burst into flames, and because the walls were covered in foam to protect those walking into the mist room from injuring themselves, within minutes the room was ablaze … Beuys stopped his performance, came out, and stood watching very quietly as these firemen arrived in full smoke protective apparatus.54

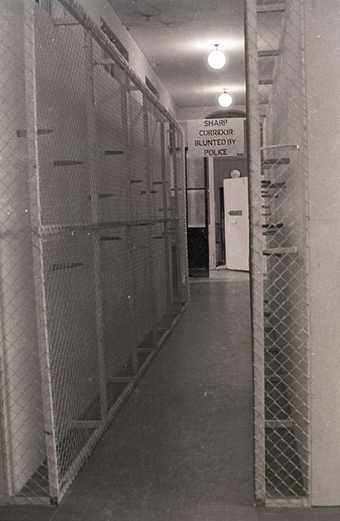

Fig.16

Günther Uecker’s Sharp Corridor Blunted by Police in the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

As the fire brigade had to deal with this dramatic incident, so the police took an interest in the activities of the various artists, including Uecker. Uecker was an artist of great importance to Demarco. By the time the Demarco Gallery opened in 1966, Uecker’s work, along with that of Heinz Mack and Otto Piene of Gruppe Zero, was already familiar to him, and he would meet Uecker in Dublin at the opening of the first ROSC exhibition in 1967. For SGA a reviewer for the Scotsman wrote: ‘personally I am looking forward to the striking nail constructions of Günter Uecker’.55 What Uecker actually created in situ was rather more dangerous – a corridor of knives. The knives were positioned sticking out from the wall of the corridor leading down to the Sculpture Department where Beuys’s The Pack could be found. Later, the police insisted on the knives being covered and so cages were used. Uecker quite liked this caged environment, which somehow added to the sinister nature of the piece. He also explicitly referred to the police intervention because across the cages he placed a banner that read ‘SHARP CORRIDOR BLUNTED BY POLICE’ (fig.16). Additionally, Uecker rigged up an unnerving banging door installation, which drew the visitor down the same corridor of knives out of curiosity, resulting in frustration outside a room a visitor could not easily enter because of the constant opening and closing.

Fig.17

Centre, left to right: Klaus Rinke, Stefan Wewerka and Günther Uecker standing with Klaus Rinke’s water hose in the entrance hall of the Edinburgh College of Art during the installation of Strategy: Get Arts, August 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

Fig.18

Visitors approaching Klaus Rinke’s water jet installation at the entrance to the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

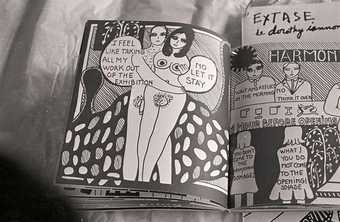

Fig.19

Two pages of Dorothy Iannone’s graphic work for the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

A work that did not attract police attention, but did annoy the City authorities was an installation by Klaus Rinke that involved a water tank and a giant hose that spouted water out of the doors of the main building as the public were walking in (figs.17 and 18). Newspaper critics responded more favourably to the humour of Rinke’s water installation with Terence Mullaly writing, ‘At once the visitor is on his guard. He is greeted at the entrance of the College of Art by a powerful jet of water’.56 And in his article ‘Giant German happening floods the Art College’, Edward Gage warned visitors, ‘as you enter, keep a sharp lookout for Klaus Rinke’s water snake’.57 The predicted scandal around the ‘pornographic’ drawings of the American artist Dorothy Iannone (fig.19), however, did not transpire. In 1969, the Kunsthalle Bern had attempted to censor Iannone's work in the group exhibition Ausstellung der Freunde by requesting that she cover up the genitals of her drawn figures. In protest the artist Dieter Roth dropped out of the exhibition and the director of the museum, Harald Szeemann, resigned. At ECA, the artists and students were expecting the drawings to be banned and were preparing to walk out in support, but in the end there was no need.58 In a letter written by Demarco to Iannone after the exhibition had closed, he wrote: ‘Everything seems to have gone magnificently. I am sending you full crits and you will see that the Police were kept at bay although they did prove to be troublesome.’59 Their proving ‘troublesome’, however, did not result in the banning of the drawings.

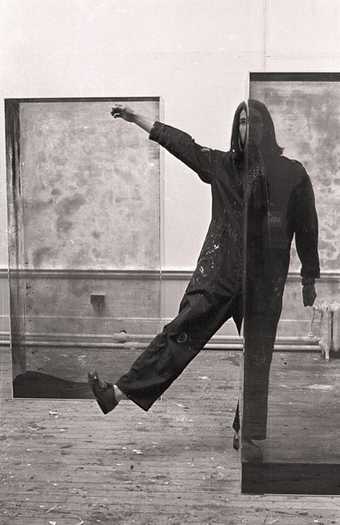

Fig.20

Alexander Hamilton (Edinburgh College of Art student assistant) with two of Erich Reusch’s triplex glass cubes during the installation of Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, August 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

Fig.21

Günter Weseler preparing his installation for Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, August 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

Other artworks shown at ECA included Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photographs of mine-rigs renamed Anonymous Sculptures and Erich Reusch’s three transparent boxes containing coal dust that had marbelised the interior surfaces (fig.20), as well as artworks by Sigmar Polke, Dieter Roth, Heinz Mack, Reiner Ruthenbeck, Lutz Mommartz, and Ferdinand Kriwet. Günter Weseler created a dramatic installation of hairy indefinable creatures, almost looking like dismembered bits of Highland Cattle, in cots, cages, or attached to walls, and rigged up in such a way that they appeared to be alive (fig.21). Of this installation, Cordelia Oliver wrote, ‘Weseler has set out his “breathing objects” furry, shaggy things that heave and palpitate, pulse and flutter in curiously organic rhythms’.60 It is not known what inspired Weseler’s furry breathing monsters, which according to Hamilton, was an installation very much enjoyed by visitors.61

One possible source of influence for Weseler might have been Thomas Theodor Heine’s poster and programme cover for the tenth Elf Scharfrichter (Eleven Executioners) Munich cabaret from 1902, which featured the cabaret singer Marya Delvard in front of eleven furry devil heads. This highly provocative cabaret, run by artists and writers who had to find ways of avoiding censorship, could be understood as a historical antecedent for some of the provocations of SGA. Another more pertinent precedent was Cabaret Voltaire, founded in Zurich in 1916. In some ways, Demarco might be compared to the Dadaist Hugo Ball (1886–1927), the internationalist impresario behind Zurich Dada. Ball was deeply drawn to Catholicism, yet had a revolutionary spirit in challenging artistic and social hierarchies, and brought about ‘total works of art’ on stage. He had also pulled together Eastern European artists with German and Austrian artist exiles, all of whom were pacifists, into his circle. Demarco recognised this connection to Dada. In his short 2006 essay, entitled ‘The Genesis and Legacy of Strategy Get Arts’, he noted the importance of the huge Dada exhibition at the Pompidou (October 2005 – January 2006), which then travelled to New York and Washington, commenting that it was a pity that this exhibition had bypassed the UK because it provided ‘vital information on the development of Dadaism, and therefore the cultural heritage shared by Strategy: Get Arts artists’.62

Press reaction on the overall impact of SGA

In the Scottish press, much ink was spilt over SGA, especially by correspondents for the Scotsman. Edward Gage, who had been the main art critic for the newspaper since 1966, was supportive of the exhibition, writing several long articles during the three-week run, but it was the charismatic figure of Beuys who continuously grabbed his attention. He wrote:

there are no less than 35 artists represented in the show – not all are German, for the city is truly an international centre – but, at its core, at the heart of its inspiration, burns the remarkably vibrant and poetic personality of Joseph Beuys. Beuys, who regards himself as an activator rather than an artist and whose very presence seems to spark off creative thought, is the well-loved and dedicated teacher, the father of happenings, the latter Day high priest of our Dada and surreal inheritance.63

Gage would write again for the Scotsman on the impact of the Festival and the ‘unforgettable’ SGA, stating that its principal effect was ‘to make us think again about the nature and function of art in society’.64 Again Beuys was his principal focus:

He carries in himself a highly original, personal and intimate kind of theatre in which he tries to inspire us all to think with the imagination and creativity of the poet or artist. His performances, like all other theatrical events, are an ephemeral art, but they are, nevertheless, laudable because they form part of a crusade to liberate and benefit society.65

Gage likewise profiled Demarco in the Scotsman. In a feature article entitled ‘Demarco: Art as an Adventure’ Gage commented on his ‘boundless energy and enthusiasm – the latter trait, although it may seem too prodigally expended at times, is truly catalytic’.66 Demarco was also positively profiled by Oliver in the Guardian in an article entitled ‘Napoleon in a Scottish pond’.67 While the title may suggest someone tyrannical, like many other critics Oliver praised Demarco’s indefatigable energy and desire to shake things up in the Edinburgh artworld: ‘For many Scots in the art business (painters arrived and painters in the process of arriving – and doing very well as they are, thank you) Richard Demarco spells danger – doesn’t anyone who deliberately opens windows in a hothouse?’.

Intriguingly, there was no strong editorial line on SGA in the Scotsman and the critic Alison Lambie held quite a different opinion to Gage or Pye on the significance of the exhibition. She was condemnatory, stating:

the decadence, the crudity, the poverty of ideas, the ugliness of some of the exhibits no doubt mirror the age we live in ... there is a slackness here, surely, a reluctance to make any effort to please or impress that links up, perhaps, with the movement taking place in many modern art-forms — a shifting away from any established discipline, a flight from assuming authority.68

The public reaction to SGA was also mixed and sometimes downright hostile, judging by the ‘Letters to the Editor’ pages of various publications, and the exhibition upset the moral rectitude and middle-of-the-road taste of many a good burgher from Edinburgh and beyond. One such letter by J.B. Chambers-Crabtree in the Scotsman even considered the exhibition ‘sick’ and ‘decadent’. Unwittingly or not, this reiterated the very same arguments that the conservative critic Max Nordau had used about fin-de-siècle culture at the end of the nineteenth century in his book Degeneration (1892), arguments that were later adopted by the National Socialists in the late 1920s and 1930s in their negative response to Expressionism. Chambers-Crabtree argued:

A strong psycho-pathological overtone is demonstrably present in almost all of the exhibits, two of which are outrageously obscene and demonstrably so. Many are no more than the crude creations that one would associate with moronic inhabitants of hospitals for the mentally disturbed. By all means let us have exhibitions of this nature in their proper place, as subjects for study by psychiatrists, but let us not mis-spend Arts Council funds, provided from the public purse, on such exhibitions at such a time.69

There was extensive coverage of SGA in the English press. In his Observer article ‘Unique Gothic rites’, Gosling credited Demarco, the Düsseldorf artists, and the German authorities for making it all possible, rather than the British ‘public purse’ as suggested by Chambers-Crabtree. Gosling also argued that Demarco had stolen a march on London curators: ‘Demarco has stepped in where London institutions have signally failed to tread (ICA, where art thou?)’.70 Simon Field for Time Out magazine made a similar remark, stating that the exhibition was an example of what the public galleries in London were failing to achieve: ‘I have never been to a more vital exhibition ... To anybody unable to get out of Britain the Dusseldorf show was a revelation; it gave a glimpse of a vitality we are only used to accepting from the States; it also presented artists, particularly Joseph Beuys, as important as anybody in the US. This was a show the ICA should have put together several years ago.’71

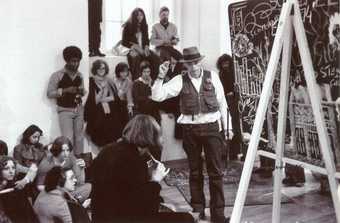

Fig.22

Joseph Beuys at the ICA during the exhibition Art into Society – Society into Art: Seven German Artists, October – November 1974

Photo © Martin Scutt

These comments are intriguing and may well have prompted curators Norman Rosenthal and Christos M. Joachimides to present the ICA exhibition Art into Society – Society into Art: Seven German Artists in the autumn of 1974. Heavily featuring Beuys, the exhibition benefited from funds made available in the wake of the UK’s entry into the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973.72 Even the title followed the palindromic example of Strategy: Get Arts. There are installation shots of the ICA exhibition which show Beuys in front of a blackboard on which he has written ‘SCOTLAND’ in large letters, indicating perhaps that he was attempting to bring some Celtic spirit to the English metropolis, or at least demonstrate a keystone moment in his own artistic development (fig.22).

A number of the press reviews of SGA considered the transformation of and challenge to the Edinburgh College of Art building. Cordelia Oliver stated: ‘former exhibitions have usually attempted to disguise it (in the Diaghilev exhibition it was merely the armature for a magnificent set piece) but Strategy: Get Arts … spills through and over it like a naughty child.’73 Edward Lucie-Smith commented that ECA was

one of those old grim, grimy art schools, battered by generations of students. Every floor looks like an original Jackson Pollock … Upstairs and down is the wildest avant-garde art West Germany can produce – which means pretty wild. … The Demarco-Dusseldorf show is shock tactics; it makes most English artists look provincial. It even makes the New York avant-garde look tame.74

Guy Brett also marvelled at the transformation of ECA by those artists who challenged ‘the feeling of musty antiquity given by the art school building, like Rinke’s coiled water canon which sends a jet through the front door that you have to squeeze past, or Uecker’s mechanism repeatedly banging the time-worn door of a life-classroom’.75 Brett was so taken by the exhibition that he felt motivated to review it twice. On 3 September 1970 he published another long review in the Times, titled ‘Up in Beuys’s Room’, in which he discussed how each artist or handful of artists had their own room in the college into which a visitor could drift, each representing a different artistic ‘strategy’, but again he reflected on how the talismanic Beuys stood out:

One discovers Joseph Beuys’s four hour ‘concert’ in this way. The room contains little more than two film projectors at different distances from an end wall, the scattering of canvas chairs, and an oasis of sound equipment on the floor where Henning Christiansen, the Danish composer who works with Beuys, crouches, continually redefining his volume and mixture of sound. If you wander in at any stage you are liable to find yourself gripped by an indefinable, intense atmosphere … In Beuys’s room, things seem to impress themselves on you by different media blending to form a strange, long drawn-out opaqueness and density.76

Gosling also wrote about SGA more than once. His second article was particularly revealing because it demonstrated how SGA had forced him to effectively re-consider his own position on traditions of artistic creation and display:

The Peculiar vibrations set up by the Düsseldorf-Demarco show in Edinburgh which I described last week still rumble on in my mind. In particular, they aggravate nagging doubts about the whole gallery set-up today. For two centuries museums and galleries have existed to display and dispose of finished art objects. But suddenly the creative current has changed course and a lot of work is being done (and I expect more to be done in the near future) which has no end product. The act of creation is itself the work.77

Fig.23

Richard Demarco (left) and Joseph Beuys at the Edinburgh College of Art during the installation of Beuys’s The Pack (Das Rudel) 1969 for Strategy: Get Arts, August 1970

Photo © George Oliver

Demarco Digital Archive

These reviews are worth citing at length because they reveal certain paradigmatic shifts in British art criticism brought about by the impact of SGA. The exhibition would also change the working practice of a number of British artists who saw it, including Alexander Hamilton. After SGA and throughout the 1970s, many curators, including Caroline Tisdall and Nicholas Serota, closely consulted Demarco when working with Beuys and curating exhibitions of his work. Beuys returned many times to Edinburgh at the invitation of Demarco, and it was through Demarco that he met other important figures from Central and Eastern Europe, such as Tadeusz Kantor. This helped draw Beuys to Poland. In 1981 Beuys would even drive in a van with his family from Düsseldorf to the Polish city of Łódź to visit Ryszard Stanisławski, the director of the Muzeum Sztuki, gifting the museum hundreds of his artworks in an ‘action’ that he called Polentransport 1981. Both Beuys and Demarco shared a strong fascination in Celtic myth and wild landscapes at the sea girt edges of Europe, but they also maintained an internationalist vision and a firm belief that the power of art could help ‘heal the wounds’ of historical conflict and alleviate the antagonisms of Europe’s geo-political divisions. Strategy: Get Arts marked the beginning of their productively collaborative friendship (fig.23) and in 1970 it was indeed the most important exhibition of German art to be shown in the UK since 1938.