While John Rothenstein’s tenure as Director of the Tate Gallery was exceptional in its length, stretching from June 1938 to October 1964, in contemporary memory it is largely defined by a single event: the ‘Tate Affair’. This failed coup against his leadership, conducted in public from 1952 to 1954, has remained a point of reference in both specialist and popular writing.1 The years that followed are easily characterised as a lame-duck coda, with Tate awaiting the new, modernist policies of Norman Reid. Subsequent journalistic commentary has taken this line, describing Reid as inheriting ‘a gallery that was dilapidated and had no clear sense of purpose’2 and which he ‘finally dragged … screaming into the twentieth century’.3 According to art historian Frances Spalding’s authorised Tate history, by the later 1950s Rothenstein had become a ‘figurehead’, albeit a ‘potent’ one, and an upswing in the museum’s reputation is credited in large part to exhibitions organised by the Arts Council, which was using Tate as its London venue at that time.4

However, limited scholarly attention has been devoted to the specifics of Rothenstein’s curatorial activities after 1954, and in particular to the way he exhibited Tate’s permanent collection. This paper aims to begin redressing that omission and to offer a fuller account of Tate’s presentation of contemporary British art in the late 1950s. It takes as its subject a largely unconsidered event, the 1957 rehang of Tate’s modern British gallery (Gallery XVII).5 Archival material is used to reconstruct how the reopened space was presented and to assess its reception, in the context of then-current curatorial approaches.6

The paper then goes on to consider the selection of specific paintings for the hang and considers interpretations of these works that were available to a late 1950s audience, specifically when viewed in the context of a display of British art. Merlyn Oliver Evans’s painting Souvenir of Suez 1952 spoke to the reverberating shocks of the previous year’s Suez Crisis, while paintings by the Australian artists Russell Drysdale and Sidney Nolan put in question the continued relevance of a global British identity. Utilising these examples, it is argued that while Rothenstein’s decision to hang the contemporary ‘British School’ apart from international works has been viewed as retrogressive, it nonetheless opened up the display to engagement with current social and political debate. In this it contrasted with the hermeticism of the dominant paradigm of modernist display, established by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.

Gallery XVII in November 1957: Presentation and reception

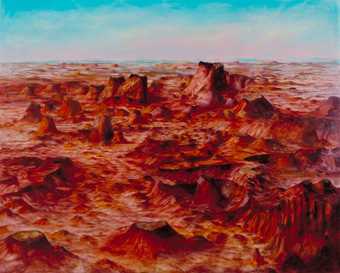

By 1957 Gallery XVII had remained unchanged for ten years and a rehang was, according to the critic David Sylvester, ‘overdue’.7 Primary evidence for the look and feel of the gallery at its reopening that November is available in contemporary press reviews and a single photograph that was used as the opening plate in A Brief History of the Tate Gallery, Pitkin Pictorials’ authorised guide to Tate published in 1958 (fig.1).8

Fig.1

View into Gallery XVII, The Tate Gallery

Photograph published on p.1 of Pitkin Pictorials’ A Brief History of the Tate Gallery, London 1958

Two features which were picked out repeatedly in the press commentary remain striking in the Pitkin photograph: the use of dark wall coverings (described as black coffee or dark tobacco by reviewers, and made of coarse linen) and the density of artworks, including some double-height hanging. The wall colour was seen as an innovative choice and, despite some small, specific objections, was judged a success. Art News and Review, for example, described how a ‘strong brown backcloth flatters, binds and gives a kick to works which have previously been damped down by more conventional hanging’,9 while for Sylvester it was ‘a brilliant stroke’.10 The density of the hang was also appreciated, with Terence Mullaly writing in the Daily Telegraph that although ‘[m]any more works than were previously shown … are on view’, the dangers of overcrowding are ‘overcome by scholarly and sensitive hanging’.11 In part this appreciation was aesthetic and included approval of the double-height display, which Eric Newton of the Manchester Guardian noted ‘with relief’ meant ‘that the pictures are no longer hung in a solid single line’.12 However, it was also an acknowledgement of the large number of post-war purchases that could now be shown, with reviewers making mention of works by Francis Bacon, John Bratby, Jack Smith, William Scott and Victor Pasmore, among others.13

A more controversial feature of the hang was the attempt to impose taxonomic order on contemporary British art by grouping works into stylistic trends. Art News and Review stated that the ‘attempted instruction of stylistic development implicit in the grouping of pictures in bays, is more ambiguous as to its success’.14 The ordering of the bays was used to create a loose overall narrative in the gallery that combined chronology with familial relationships. In the absence of any definitive documentation, this narrative can be partially reconstructed from the press coverage.

At the entrance, Wyndham Lewis’s 1923–35 portrait of Edith Sitwell (Tate N05437) stood to the left, initiating a series of bays oriented broadly towards abstraction and which progressed from vorticism through to 1930s geometric abstraction (an early John Piper is visible in the Pitkin photograph) and contemporary constructivism (including the new Pasmore). On the right of the entrance Paul Nash’s Totes Meer (Dead Sea) 1940–1 (Tate N05717) stood at the head of bays comprising varieties of figuration, with groupings (again partly visible in fig.1) that focused on the Euston Road School, Graham Sutherland and neo-romanticism, and the nascent Kitchen Sink realists.15 The latter concluded with John Bratby, before a double-height hanging of Francis Bacon was used to unite the two sides. This ‘pattern of opposition’16 was by no means absolute; Art News and Review noted acerbically that ‘by time the suggested streams reach the other end of the gallery the Minton-Craxton wall seems to have crossed over and there is an uncomfortably wrong juxtaposition of a good Scott under a good Bratby’.17

From the critical commentary it appears that the physical construction of the bays was new in 1957, but, more fundamentally, so was a didactic approach to hanging contemporary British art that encouraged the visitor to think in terms of conceptually related artists and works. As noted, there was some discomfort with this approach. The reviewers’ language largely avoids stronger notions of ‘school’ or ‘movement’, preferring to talk of ‘trends’, ‘kinds’ or ‘sub-groups’.18 For Art News and Review classificatory rigour went against the grain of British art: ‘The snag about making such nests of British paintings is that there are so many cuckoos about. Eccentricity rather than intellectualism is the bastion to which most wilful painters ascend.’19 On the whole, however, reviewers of the rehang were uncertain rather than hostile, combining reservations with positive comment on the ‘intelligibility’ of a ‘more coherent’ arrangement which remained ‘not too blatantly instructive’.20 Only Sylvester hints that the approach could have been taken further, praising it as ‘rather more systematic’ than past attempts.

The template for displays of modern art had been set in 1939 by the opening of MoMA’s purpose-built gallery. Museum studies literature has itemised the key features of ‘the MoMA idiom’ and their continued influence, and argued for the way that these informed the visitor’s experience.21 Austere, white-walled galleries and isolated works signalled quality, seriousness and a machine-age modernity; connotations reinforced by domestic-scale rooms that suggested the homes of wealthy patrons or fashionable stores. Reviews of Tate’s 1957 hang make clear that classificatory schema and a strong didactic emphasis in presentation were also seen as American influences. In the News Chronicle Wilma May-Thomas notes negatively that ‘American galleries take their job as teachers very seriously: they surround modern paintings with notes and photographs of other relevant pictures’.22 In fact MoMA itself eschewed explanatory material, its didactic burden carried solely by the visual arrangement; an approach which, on the evidence of the Pitkin photograph, was also used at Tate.

In its aesthetics Tate’s 1957 design for Gallery XVII thus made a nuanced response to what had become the MoMA-led orthodoxy. On the surface, nothing could be more different to the ‘white cube’ paradigm than textured, chocolate-coloured walls and double height pictures (in 1964 the installation Painting and Sculpture of a Decade ’54–’64 by architects Alison and Peter Smithson was to show how a more typical modern display space could be carved from Tate’s halls). However, the Pitkin photograph shows how the wall coverings, the uneven line of pictures and the asymmetrical bays in fact worked to temper the high ceilings of the room, going some way towards the domestic feel of the modern gallery. Moreover, despite the density of pictures, clarity is a common theme among the reviews.23 For Sylvester, Tate’s neo-classicism was inherently antipathetic to abstract work, but he praises Gallery XVII for at least making the best of it.24 In its look and feel, the 1957 hang thus involved compromising with the existing Tate architecture but utilised some surprising, even old-fashioned techniques to deliver a modern visual impact. Where the influence of the MoMA idiom showed more directly, and, as noted, more controversially, was in the adoption, at least in part, of a didactic, classificatory approach to its layout.

John Rothenstein and the ‘British School’

The thinking behind the hang can be attributed to Tate’s Director, John Rothenstein. His formal title as ‘Director and Keeper’ looked backward, with its emphasis on supervision over display,25 and the developed concept of a curator as creative actor largely lay ahead, formulated through the activities of Lawrence Alloway and others in the 1960s.26 Yet Rothenstein placed great importance on this aspect of his job, reflecting that of all his duties it was hanging the collection ‘which gave me beyond comparison most pleasure’.27

Rothenstein was not, however, a neutral figure. As Director for nearly twenty years by 1957, his biography and approach had reinforced an existing ambiguity in Tate’s reputation. From its foundation as the National Gallery of British Art in 1897 the institution had had a complex relationship with the avant-garde. On the one hand, self-declared ‘independent’ artists such as Walter Sickert were critical of the institution, believing an official gallery would ossify a single, conservative conception of modern British art.28 On the other, Tate soon established a reputation with the broader public as an advanced guard for the modern and modernism; a reputation cemented after the Second World War when it reopened with exhibitions of Georges Braque and Georges Rouault, Paul Cézanne and contemporary British painting.

Rothenstein himself existed squarely within traditional networks of power. The son of the painter William Rothenstein, he was knighted in 1952 and, according to his name-dropping autobiography, served as Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s unofficial art adviser.29 Indeed, when political journalist Henry Fairlie first coined and then elaborated upon the term ‘the Establishment’ in the mid-1950s, Rothenstein was cited in evidence:

In order to see the Establishment in full array one must go to an Arts Council reception or a party given by the New Statesman and Nation … Then, as one trips over the feet of Sir John Rothenstein only to fall into the arms of Sir George Barnes one begins to understand how men of great power and great wealth become enmeshed by the Establishment.30

The key ambiguity was thus not over Rothenstein’s membership of ‘the Establishment’ but over whether a unified position on contemporary art could be identified with it. In one view, illustrated by Evening Standard cartoonist Low, Rothenstein was the metropolitan modernist general, seeing off the ‘low-brow cavalry’ of country squires and angry housewives from the gallery’s steps.31 Rothenstein’s view of himself, however, was that he was increasingly oppositional to ‘a new “establishment”’ which he believed to be promoting a narrow orthodoxy of abstraction and avant-gardism from seats of power in ‘the Arts Council, the British Council, the Contemporary Arts Society and the Institute of Contemporary Arts’.32 From another perspective again, would-be iconoclasts saw all those with institutional power as hopelessly reactionary. Looking back on the late 1950s, the art dealer John Kasmin damned the whole London art scene and Tate in particular: ‘the critics were crummy … the galleries were dull … The Tate Gallery was not worth talking about. We thought we were in a wilderness.’33 Thus, at the reopening of Gallery XVII, Tate and its Director were perceived both as progressive champions and as reactionaries, depending on how these terms were understood.

The most immediate way in which Rothenstein’s intellectual preferences showed themselves in the 1957 hang was in the very idea of a separate modern British gallery, where contemporary works were contextualised by a preceding suite of national, chronological rooms and isolated from recent international comparators; Tate’s modern foreign holdings being, to use Spalding’s phrase, ‘confined … to the lower galleries’.34 Rothenstein’s commitment to the ‘British School’ was well established,35 and for his detractors it demonstrated the ‘parochial and genteel’ interests which enforced conservatism on Tate.36

As a partial consequence there were repeated attempts to form a rival museum of modern art which would be overtly international. These plans came somewhat to fruition with the formation of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1947,37 but this thinking also informed Reid’s early reforms at Tate after 1964. Central to Reid’s reputation for shaking up an obsolescent institution was his inversion of Rothenstein’s ‘British School’ approach to contemporary art, creating instead ‘a separate modern museum within the Tate’ which crossed national boundaries.38 In the Tate Gallery Report for 1965–6 Reid gave a rationale for his revision: ‘the previous system of making a rigid separation between the British and foreign works has been abandoned … The highly international character of much of the art being produced today makes purely national divisions of this kind illogical’.39 Instead Reid organised contemporary works under stylistic headings, radically extending the controversial taxonomic approach that had been introduced in Gallery XVII in 1957 – and which had by this point become established – but this time with categories defined for an international population of works.

However, it is anachronistic to read Rothenstein’s approach through Reid’s later disavowal, seeing it as outmoded or inherently reactionary. The concept of a national school remained common currency among academics and administrators: it framed, for example, much discussion of American abstract expressionism, including Gabriel White’s preface to the catalogue for The New American Painting exhibition at Tate in 1959.40 Nor should Rothenstein be understood as claiming that contemporary British work fell within a unitary tradition. As his guidebook text acknowledges, Gallery XVII exhibited a range of ‘Contemporary Tendencies’.41 Indeed, this diversity within Tate’s twentieth-century British holdings was to prove a challenge for Reid. While after 1964 some modern British art was incorporated into the new international stylistic classifications (Pasmore, for example, being shown in the ‘Constructivism and Abstract Art’ room), a large portion (including post-war work by Edward Middleditch, Jack Smith and Lucian Freud) remained unassimilated and displayed in two twentieth-century British rooms. Now, however, it was the modern British works which were condemned to the basement.

Critical readings of the MoMA idiom have noted how the taxonomies underlying display (typified by the ‘evolutionary tree’ of modernism produced by MoMA’s first Director, Alfred Barr, but also apparent in Reid’s revised layout) have emphasised the internal evolution of modern movements and styles, presenting this evolution as an essentially aesthetic progression between artistic categories.42 This, it is claimed, along with a somewhat sterile presentational style, has acted to isolate the art shown from the complexities of history unfolding beyond the gallery walls.43 In contrast, while Rothenstein’s 1957 hang in Gallery XVII adumbrated a taxonomic approach, by utilising the traditional notion of a ‘British School’ as its fundamental organising principle it also bound itself to an inherently social and political category: British nationhood. The display thus held out the promise to the visitor of some connection between the art on show and contemporary Britain, and did so at a time when, as the country retreated from empire, British identity was fracturing.44 The remainder of this paper asks whether, and how, this promise was delivered. It examines the selection of specific works for inclusion in Gallery XVII and considers their potential meaning for a late 1950s audience when hung in the context of the ‘British School’.

Souvenir of Suez: Merlyn Oliver Evans

Fig.2

Merlyn Oliver Evans

Souvenir of Suez 1952

Tate N06147

© The estate of Merlyn Oliver Evans

Cropped at the left but clearly visible in the Pitkin photograph are the angular shapes of Merlyn Oliver Evans’s Souvenir of Suez (fig.2). Completed in 1952, the painting was rooted in Evans’s memories of his army service in North Africa during the Second World War.45 However, for Tate visitors in 1957 a reminder of Suez would, inevitably, resonate primarily with more recent British military action: the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt during the 1956 Suez Crisis. There is no documentary material relating to the decision to include the picture, which had been purchased in 1953, in the rehung Gallery XVII. However, given the recency of the crisis and its significance to the public (45,000 British servicemen had been deployed and in January 1957 the Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, had resigned), it is implausible to see the painting’s inclusion as anything other than a conscious act, in which Rothenstein would have considered the political interpretations that the painting offered to visitors.46 Certainly the picture held visual reminders of reporting of the crisis: the entangled framework of Evans’s central construction and the long, straight plane of the canal echoed recent news photographs.47

The Suez Crisis had divided Britain in late 1956. When Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s military government nationalised the canal in July, many saw a genuine threat to international freedom. However, the British government’s opposition also had a clear basis in self-interest: the canal provided an important route for troop and oil transportation. It was the turn to a military response that polarised public opinion, with Anglo-French forces invading the Canal Zone in November, storming Port Said with heavy civilian casualties. While mounted police held off protesters in Downing Street, a poll of 550 Londoners showed a solid 272 approving of the intervention.48 At stake were views on Britain’s identity in the post-war world. For supporters, Britain’s interests remained inherently international and justified overseas intervention. For opponents, Eden’s belligerence failed to grasp changed, post-imperial realities within a new, rule-governed international order; a position reflected in protesters’ chants of ‘Law not war’.49

The implementation of a ceasefire on 6 November, under American pressure, cemented a slim popular majority behind Eden, with fifty-three per cent approving of the government’s actions in a Gallup poll conducted five days later.50 However, a particular and slightly menacing post-Suez mood remained, forming the context in which Souvenir of Suez was hung at Tate a year later. At the end of 1956, Ian Gilmour, editor of the Spectator, described a ‘semi-fascist atmosphere … [where] it is considered treacherous to whisper a word of criticism’,51 while in February the following year Richard Crossman gave a lower key description of this culture of silence: ‘[t]hough the whole foundations of the country have been shifted by the earthquake, we are inclined to deny that it ever occurred’.52 In this circumstance, hanging a painting with a title and content which not only invoked Suez, but, as a ‘souvenir’, commended the viewer to remember it, might be interpreted as an unambiguous act of protest by Rothenstein and a reflection of the liberal values of ‘the Establishment’ posited by Fairlie.53 The picture itself, however, complicates such a straightforward explanation.

Fig.3

Merlyn Oliver Evans

The Conquest of Time 1934

Tate T00830

© The estate of Merlyn Oliver Evans

On the one hand, Souvenir of Suez could indeed be read as a critique of imperial aggression. Evans had been on the edges of the pre-war London surrealist group but, following service in North Africa and Italy, his work became dominated by violent, anti-war allegories painted in an idiosyncratic vorticist style. In the early 1950s he returned to a personal motif: abstracted forms based on dockside machinery which he had deployed in earlier compositions, such as the oil painting The Conquest of Time 1934 (fig.3), but which now continued his post-war theme in terms of the angular violence of the imagery. As a boy Evans had grown up near the Glasgow shipyards and developed a particular reading of the shapes he found, making a link between cranes and aggression: ‘I realized that the shapes could take on an emotional quality which might convey elegance or heaviness, a menacing brutality or a sense of refinement or repose. Derricks and cranes, and dock-side machinery, had a fierce, heavy – sometimes predatory – feeling’.54 Thus, Souvenir of Suez – a calm landscape, bisected by an orderly horizon line and in naturalistic colours which convey the cool of blue water and the sun-lit warmth of yellow desert – has, squatting at its centre, a predatory, mechanical monster, helpfully coded in red, white and blue. Thus, through its inclusion in the 1957 hang, Evans’s reflection on his wartime experience is recuperated as an attack on Britain’s more recent Suez policy.

On the other hand, however, key features of the painting suggest other, more nuanced interpretations. While the central form references a dock crane, with its surmounting of hooks, it is as much architectural as mechanical. The colour is that of stone, not metal, and instead of diagonals there are solid horizontal forms, reminiscent of ancient Egyptian entablature (for example in the squat, squared arch structure that supports the hooks at the top right). The dominant shape is the triangle, sometimes complete, sometimes squared off at the top; indeed, the whole central form can be resolved into a disordered isosceles triangle. This emphasis has an obvious association with pyramids,55 but also makes a visual reference to a pair of mason’s compasses, for example in the inverted V-shape, framed against the sky at the top of the form. In both cases, the connotations are of precise and enduring construction, not predation.

While references to ancient Egyptian architecture might be taken as positive symbols of modern Egyptian nationhood, other associations put greater weight on a wider classical tradition. Evans had previously expressed his desire to imitate the timeless qualities of ancient Greek art,56 and in Souvenir of Suez the repeated invocation of the regular triangle suggests the similarly fixed principles of ancient Greek geometry. Moreover, while the features on the far side of the canal in the painting again invoke dockside machinery, there is also a suggestion of the ancient Lighthouse of Alexandria (built between 280 and 247 BC), as featured in the modern flag of the city. These associations of the architectural forms with Hellenic tradition serve as a reminder that modern Egypt is itself the complex product of a long history of colonial occupation, starting with the Greeks of Alexander the Great and proceeding via Rome and the Arab conquest. A final visual association of the central form returns to its mechanical aspect. Evans’s use of triangles, horizontal projections and supporting lines (for example, immediately below the red and blue shapes at the mid-right and left of the central motif) suggests the large steam dredgers, with their extensive rigging and projecting conveyor belts, used by Ferdinand de Lesseps in the construction of the canal for the French-dominated Suez Canal Company in the 1860s. On this reading, the central form becomes the creator of the scene, rather than a predatory interloper, while the painting as a whole offers a network of associations that celebrate the permanence of rational construction whether by ancient Egyptians or later imperial interests.

Evans’s Souvenir of Suez, and Rothenstein’s gesture in including it within the 1957 hang, thus opened multiple interpretative possibilities for visitors. However, in the aftermath of the Suez Crisis the preferred stance was, as Ian Gilmour and Richard Crossman described, a simple mental denial of events and, in that context, including the picture in the modern British gallery was an unambiguous challenge to silence. The painting was a reminder of the previous year’s images and events, but in its ambiguities it also evoked their complexity. Its hanging thus helped realise the connection between contemporary art and contemporary Britain which, as has been suggested here, was promised through the presentation of that art in terms of a ‘British School’. Moreover, it was this context of display that gave particular force to Souvenir of Suez as a signifier of the recent Suez Crisis and the questions about Britain’s identity that had been raised; the picture being placed at the conclusion to Tate’s full chronological hang of British art, itself a visual analogue to the long evolution of nationhood.57

Not strictly speaking British: Russell Drysdale and Sidney Nolan

Rothenstein’s commitment to the ‘British School’ as an organising principle in his curation meant that, of necessity, defining the borders of Britishness was a prerequisite for deciding which works could be hung. In the midst of Britain’s rapid exit from an established imperial role, however, such curatorial decisions could not rest on any easy consensus about where the boundaries lay. This was particularly true following the ‘watershed’ of Suez, when previously dominant conceptions of Britishness as a global identity, encompassing a family of far flung dominions, were further eroded.58 The impact was particularly significant in relation to those realms, including Australia, which lay to the east of Suez and for which the canal provided an important physical connection.59

Rothenstein’s own doubts about where to draw the limits of British identity, in particular when thinking about the ‘Old Commonwealth’, were made explicit in a Tate Board discussion in September 1957, ahead of the reopening of Gallery XVII and following the purchase of two works by the Australian painter Sidney Nolan.60 Commonwealth pictures, Rothenstein said, ‘were not strictly speaking by British artists but still less could be hung with the foreign pictures’.61 In the event, two Commonwealth artists were included in Gallery XVII when it reopened two months later: Nolan and his fellow Australian Russell Drysdale.62 Despite Rothenstein’s hesitancy, the hang thus made concrete a continued adherence to the idea of a global Britishness which stretched beyond the home nation state (that which was ‘strictly speaking’ British) to include a notion of shared culture and tradition, and potentially race, with the realms of the Commonwealth.63

Colonial art had, in fact, long found validation by being shown in Britain and as part of a British vision. Australian landscape in particular was a familiar element of London exhibitions, from the work of émigrés such as John Glover and Nicholas Chevalier to Arthur Streeton’s Golden Summer, Eaglemont 1889 (National Gallery of Australia, Canberra), displayed at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1891.64 Rothenstein’s annexation of Australian paintings to the ‘British School’ thus continued an existing practice, but their inclusion in the contemporary British display also reflected rising interest in a new generation of Australian painters who offered a less familiar presentation of their own country, or, in some cases, located their interests elsewhere, with an international avant-garde.65 In the summer of 1957, for example, the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London had held a solo show of Nolan’s work. This was followed by the more comprehensive Whitechapel exhibition Recent Australian Painting, in 1961, and Tate’s own Australian Painting – Colonial – Impressionist – Contemporary in 1963.

Further consideration of Tate’s paintings by Drysdale and Nolan, however, indicates the difficulties involved in an easy appropriation of Australian cultural identity by a London gallery in the late 1950s. While Rothenstein felt that these could not be ‘hung with the foreign pictures’, the works resist complete assimilation to a global Britishness and threaten even Rothenstein’s tentative assertion of that identity.

Russell Drysdale had had first-hand exposure to the pre-war European avant-garde, but from the mid-1940s adopted a largely naturalistic style. His innovation was in his subject matter and his palette, and the anxiety these expressed about Australians’ hold on their continent. Before Drysdale, the country’s interior had been almost invisible within Australian culture; an unwanted other haunting the back of its modern cities.66 The artist, however, swiftly established an iconography of isolated outback hamlets and lethargic, itinerant inhabitants, utilising red-tinged glazes to materialise the interior’s dryness and heat.67

Fig.4

Russell Drysdale

War Memorial 1950

Tate N05986

© Tate

War Memorial (fig.4), painted in 1950 and purchased by Tate in 1951, is characteristic of this iconography and style. The road which dominates the foreground suggests isolation more than connection, passing through the settlement from unknown origin to unknown destination; the presence of buildings simply emphasises the absence of people. Drysdale wrote of the picture that the ‘subject is of no particular township but rather is representative of the small bush community with its cheap, cast figure (there must be hundreds of them) looking completely unreal and out of key’.68 It was this cast war memorial that provided the most potentially unsettling element for Tate’s British audience. On the one hand, it was a sign of Australia and Britain’s shared history of commitments and sacrifices, and a common culture of ubiquitous memorialisation. On the other, this very familiarity emphasised the strangeness of the particular Australian context: the red and yellow dustiness is the antithesis of the imagined setting for a typical British village war memorial, placed in a green or churchyard. As Drysdale noted, the outback landscape itself appears to render alien the very act of remembrance, and the memorial becomes almost absurd, the figure’s purposeful march mocked by the absence of anywhere to which to march. If Drysdale’s memorial represents a common, global British culture, it seems to have been rejected by his depiction of the land.

Although Drysdale’s outback landscapes had immediate success, it was Sidney Nolan who became the most prominent of the new generation of Australian artists, moving to London in 1951. Nolan, too, turned attention to the interior, with landscapes such as Tate’s Inland Australia 1950 (fig.5). However, his reputation was established by his Australian history paintings, in particular those featuring the executed outlaw Ned Kelly, such as Glenrowan (fig.6). This was painted in 1956–7 and purchased immediately by Tate along with Women and Billabong 1957 (fig.7),69 one of Nolan’s paintings about the shipwreck and survival of Eliza Fraser, a celebrated story of suffering, perseverance and betrayal in the Australian wilderness in the 1830s. Organised into series, these pictures told stories that were already semi-mythical, an aspect Nolan emphasised through the simplicity of visual presentation and the repetition of motifs, such as Kelly’s armour, across the paintings that comprised a series.

Fig.7

Sidney Nolan

Women and Billabong 1957

Tate T00151

© Sidney Nolan Trust. All Rights Reserved, 2018/Bridgeman Images

For Britons at Tate, Nolan’s work offered connections back to their own national painting traditions: to the history painting championed by Joshua Reynolds and, more immediately, to the narrative works of artists such as Luke Fildes and John Everett Millais which had dominated taste in the later nineteenth century.70 It also, however, put in question the morally fortifying content that had been at the heart of this narrative tradition. The Australian national myths which Nolan cemented were deeply ambiguous, combining survival in the wilderness with elements of defeat or betrayal. In Glenrowan the injured Kelly – trapped within the helmet which acts as his attribute across the series – has the downcast eyes, viscous tears and thin beard of Christ as the ‘Man of Sorrows’. It is unclear, however, if this is the outlaw’s apotheosis or an underscoring of the bathos of an Australian national legend founded on a failed bandit. In Women and Billabong, Mrs Fraser appears helpless, lacking any visible limbs to counter the multiple entangled branches of the trees which confront her; she is as out of place as Drysdale’s cheap metal soldier.

Nolan’s paintings thus presented an uncertain retelling of Australia’s national myths, and in doing so within Tate’s 1957 rehang, they also chaffed against their appropriation to a ‘British School’. The works gestured towards a British narrative painting tradition, but then undermined that tradition’s moral certainty and used it to address explicitly Australian concerns. It was a combination of shared tradition and increasing separation that articulated the underlying reality of the countries’ changing political and cultural relationship.

Despite this tension between an Australian and a global British identity being played out at Tate, by the turn of the 1960s aspects of Australian art were moving away from a focus on national questions altogether.71 Tate’s 1963 exhibition Australian Painting – Colonial – Impressionist – Contemporary, which was hosted by Rothenstein but selected by the Australian Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, received a mixed critical reception.72 Many commentators appeared to expect the exhibition to demonstrate the flowering of an ‘Australian School’ and when it instead showed a wide variety of content and style, both figurative and abstract, the result was confusion and some disappointment.73 Among the artists included in the ‘Contemporary’ section of the exhibition there was also frustration. Several found their placement at the apex of a national historical tradition anathema, as their intention was to locate themselves within a modernism that was international.74

A year after Australian Painting – Colonial – Impressionist – Contemporary, Norman Reid took over as Director of Tate, and the reorganisation of the museum’s contemporary collection into a discrete, stylistically organised, and, above all, international display commenced. The presentation of modern British art was thus reshaped by the same pressures that had been made evident in the Australian exhibition in 1963: an increasing diversity within national art production, and a generation of artists who saw themselves as international practitioners. However, to understand Rothenstein’s ‘British School’ approach of 1957 as simply outmoded (or ‘illogical’, in Reid’s terms) is to miss how bringing a concept of nationhood into the gallery enabled art to illuminate the tensions within a British identity in transition.

Exhibition history and the permanent collection

Significant scholarly attention has focused on exhibitions as self-conscious cultural interventions. The resulting ‘exhibition histories’ have been presented as both a novel and a significant turn in art history, to the extent that in 2007 curator Florence Derieux could claim that it ‘is now widely accepted that the art history of the second half of the twentieth century is no longer a history of artworks, but a history of exhibitions’.75 However, as much as any existing art history, this literature reflects its practitioners’ preferences in its selection of the objects of study from among the wider field of art exhibitions. Curator João Ribas opens his 2015 essay on solo exhibitions by observing that the field is ‘largely written around a single typology, that of the “paradigm-shifting” group exhibition’; but while Ribas extends consideration to the paradigm-shifting solo exhibition, the idea remains that interest lies in moments of (perceived) challenge to the existing canon.76 Such an emphasis has led to limited analysis of the displays of art subject to this confrontation, including the display of permanent collections in national public institutions such as Tate.77 There is thus the danger of exhibition histories offering only a partial account, ignoring mainstream positions and tastes, but also of missing the possibilities for meaning created by the coalescence of a state institution, a broad public and contemporary art.78

The example of Tate’s 1957 rehang gives an indication of these possibilities. As the first part of this paper has shown, the hang was an idiosyncratic but largely successful attempt to improve the presentation of contemporary British art at Tate, and its layout and display techniques were informed by evolving international practice. Given John Rothenstein’s centrality to this effort, it counters the common picture of his leadership as moribund following the conclusion of the Tate Affair. On the other hand, his commitment to a concept of the ‘British School’ as a key organising principle for display ran against contemporary trends, and Norman Reid’s subsequent shift to a stylistically organised, international display (as well as a reversal in the relative prominence of British and foreign work) has made Rothenstein’s approach seem anachronistic to many commentators. However, by retaining a social and political concept (that of the British nation) in the curation, Rothenstein’s hang also retained a point of contact with the complexities of history going on beyond the gallery walls, countering the claims of aesthetic isolation made by critics of the MoMA idiom. In the context of the hang, Evans’s Souvenir of Suez, although painted in 1952, became a potential meditation on the recent crisis, and works by the Australians Drysdale and Nolan became tests of the relevance of a global British identity. In each case, the framing of the painting through the concept of contemporary British nationhood gave it a particular pertinence.