Collaboration is at once both intimate and expansive. It depends on opening up to another person and in that process of opening up, building a bond of trust supportive enough to create something else. The movement for women’s liberation during the 1970s depended on coming together to negotiate and navigate these shifting boundaries. Working together meant that women were supported on a smaller, more personal level to initiate change on a larger one. It meant that women’s liberation could become a mass movement without central organisation, but also that many women were politicised by talking about and listening to personal experiences. Women collaborated on their activism, sharing workloads, as well as using new forms of communication to realise the international spread of the movement. Far from a smooth sisterhood, these collaborations were marked by divergent opinions that took feminism in various directions. In these different ways they created a feminist politics. This article focuses on interactions between women artists, specifically in relation to consciousness-raising groups, exploring how collaboration impacted the work of art and created a feminist politics.

Consciousness-raising groups sprang up in different places and at different moments, but often as a foundation for women’s political organising. They provided sites for women to come together and talk about their lives, to excavate their assumptions and to trace patterns of feeling and behaviour. For the most part, many of these women were white, middle-class and motivated by the gender oppression they faced in other social movements or in the home as readers of texts like Betty Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique.1 In consciousness-raising groups women peeled back the layers of expectation that had been placed upon them to expose the raw, unmoulded and sensate self beneath. It was a process of politicisation achieved through self-reflection that took place in the company of other members of the group. In this context, new and intimate relationships between women disrupted the isolation felt at home, at work or in public spaces, and although these often depended on locality, women also interacted across geographical distances. Reading collaboration through consciousness-raising, then, depends on rethinking that process and the intimacy it demanded from participants, specifically by forgoing immediacy and proximity as necessities and understanding how mediation, both linguistic and material, structures interaction. It is with this in mind that collaborations between women artists – which extended from discussions to sharing and co-producing artworks – are crucial for thinking about the feminist politics of collaboration.

This paper looks at two art projects: the Postal Art Event 1975–7 and London/LA Lab 1981. These collaborative projects delineated a space for women artists to develop, exhibit and converse about their work, creating an alternative environment for creative experimentation that abandoned isolation and objectivity.2 In this space, production and exhibition were resituated in the midst of dialogue, with artworks being exchanged and the subject of exchange. This meant communicating differences across distance and making intimate experiences public and legible. This article will emphasise the intimacy and therefore the risk involved in such a practice. This is gestured to in the title, which echoes a first encounter with nakedness and sexuality as well as the ‘reveal’ in a high stakes card game. These diverse scenarios, in turn, relate to the differences between private and public interactions, as well as the sense of danger and threat that accompanies pleasure. It is among these artists’ attempts to bridge the strict division between public and private spheres, as well as attendant difficulties, trepidation, solidarity and humour that the Postal Art Project and London/LA Lab will be situated. This article discusses the effects of these collaborative projects in three related sections: the first focuses on the foundation of a new framework to make and show artwork; the second on the concomitant breakdown of domestic isolation; and the third on the representation of a powerful and empowering community of women.

I’ll show you mine: sharing stories and collaboration

Both the Postal Art Event and London/LA Lab depended, like the consciousness-raising process, on sharing stories, although this was reoriented from the intimate space of a small, regular group meeting. The Postal Art Event connected women in different cities, towns and villages in England through the exchange of artworks via the mail. The event extended to include numerous exhibitions in different UK cities and gradually accumulated the variant titles Feministo and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman/Housewife.3 London/LA Lab brought together artists based in London and Los Angeles, collapsing the distance between them so that one another’s voices could literally be heard. This was reflected in the provisional title of the event: We’ll Decide on a Title When We Meet.4 The various titles that accompany both of these projects gesture to their contingency; they were in a state of flux and responsive to the actions and desires of their participants.

Despite differences in form – objects small enough to be sent through the mail in Postal Art Event and performance in London/LA Lab – art mediated the collaboration between women in both projects. Unlike other postal art networks, performance showcases or exhibitions in the 1970s, these two projects were not solely concerned with circulating already-existing work or the names and motifs of particular artists, but instead allowed the process of coming together to shape the artwork.5 In London/LA Lab this took the form of a performance programme pairing one artist from London and one from Los Angeles, with one pair performing each night over the duration of the event. The women not only performed together, creating a new context for their work, but they also spent time together, forming new relationships. In a comparable way Monica Ross, a participant in the Postal Art Event, described that event as ‘a non stop process, new work constantly emerges as a visual conversation develops. The aim is communication, not perfect aesthetics.’6

The processes of communication and the relationships between women in these two projects were quite different. The Postal Art Event, despite the allusion to a one-off occurrence in the title, in fact entailed a process of ongoing exchange between 1975 and 1977, whereas London/LA Lab took place for a limited period of time in 1981 at Franklin Furnace in New York – a city in which none of the participants lived but which had a ready audience. Whereas the former project built up a sense of community over time, the latter failed to cement relationships between the participants, as an article published in Fuse suggested: ‘The long-distance symbiosis didn’t materialise, and in the end what remained were the differences.’7 Nonetheless, both were events of sorts and both were structured as something continuous, without a sense of foreclosure or an end product in mind. They also depended on being framed as a connected set of exchanges. As such, the form of the event provided an impetus for women isolated in the home to make work and, initially at least, to circulate it beyond the art world. The ‘event’ provided enough of a structure to mobilise the women to share their work without determining its content and form in a way that was similar to the consciousness-raising process, which had its own set of rules.8

The Postal Art Event could be, and was, imagined as a ‘long distance consciousness-raising session’.9 It was originally conceived of as a means of communication between two neighbours, Sally Gollop and Kate Walker, when the former moved away. Both women were feminists, mothers and artists. The initial postal exchange replaced the support and encouragement they had shown each other in proximity, opening up another channel to develop their political consciousness while making artwork and caring for families. The objects were determined by what was to hand at home, as well as what could be posted. The small scale of the work along with the intimacy of the interaction also confronted other, more public discussions of feminist-influenced art. In an important intervention, Walker spoke up at the 1975 Women’s Art History Conference in London to recruit more members to the art exchange. Another participant, Su Richardson, paraphrased Walker’s call to arms:

Look aren’t there any housewives here who want to make some art, and who are fed up with all this fine art business? Aren’t there any of you making things at home that you’d like to show each other?10

This call asked for a change of focus. Instead of directing thought and developing strategies for women to enter into ‘all this fine art business’, which was perhaps epitomised in the emphasis on expert speakers at the conference, Walker’s comment proposed a look sideways to ‘each other’. While this did fit with the shape and arrangement of bodies in a consciousness-raising circle, it conflicted with the desires of other feminist artists and critics to enter and agitate fine art institutions, the commercial art world and the discourse of art history.11 However, by foregrounding the relationship between women and constituting this as an alternative audience for the work, Walker made a radical claim for a different kind of artwork, rooted in the home as a site for art-making as well as care. Her mobilisation of the home resulted in a new and more sustained critique of the situation of the housewife – as well as, at times, a celebration of love and family – and a reformulation of the artist as one who made art among other types of work and in response to their environment.

The Postal Art Event broke women’s isolation in the home by offering connections to those who lived elsewhere and providing another identity beyond that of mother, wife or carer. This, in turn, offered the women a space of reflection and an outlet for feelings of both happiness and frustration. It meant agency and a chance to investigate one’s own subjectivity. While this had been the work of consciousness-raising, the Postal Art Event also mobilised the home as site to make work and as a space worthy of analysis, not just the other, shrouded side of the public–private binary. In this way it provided the means to investigate the particular material conditions of being a housewife. Quite literally, it entailed the mobilisation of the home as a political site through the circulation of domestic bits and pieces in art objects.

The artworks produced for the Postal Art Event were mostly small and lightweight, shaped by the demands of postage costs. Some were postcards or sections of text; some were objects made using craft skills, like crochet or embroidery; others were comprised of materials gleaned from the home including old packaging, pins and garden seeds. Each object was sent to only one interlocutor, but a participant could have as many respondents as she wished. Sometimes ‘conversations’ developed between correspondents who would tailor their next work according to the form or content of what they had received. At other times a woman might pursue her own idea or send multiple objects on a related theme to different women. Su Richardson, for instance, made a series of crochet plants – one in blossom was sent to Kate Walker as a gift, while another cactus-shaped one, stuffed with pins, was made for a less supportive friend (figs.1 and 2). The malcontent that appeared in this latter piece was evident in other works, so that irritations as well as affinities animated the exchanges in the Postal Art Event.

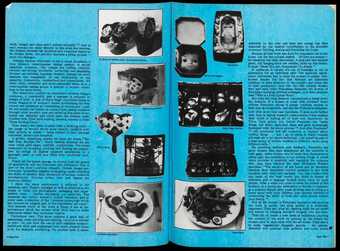

Fig.1

Page spread from Spare Rib, no.60, July 1977, pp.6–7, illustrated with unattributed artworks, including Sanctuary at the top right of p.7

British Library, London

It is impossible to trace many of the trajectories that the objects took; most exist only in reproduction and those that are extant are in the personal collections of the original makers.12 Nonetheless, documentation in Spare Rib (fig.1), the artist’s zine MAMA: Women Artists Together (fig.2) and the Women’s Artists’ Slide Library show repeated motifs and visual echoes between the works.13 Art historian Alexandra Kokoli has analysed the exchange of objects as a process of defamiliarisation and ‘undoing homeliness’, which destabilised the naturalised connection between women and the home.14 Certainly, many of the works explore this theme, with windows appearing and reappearing across multiple objects as if commenting on the limited perspective from the kitchen window. Bodies, figures and faces merge and re-emerge, sometimes mutating into furniture, suggesting that the individual had become inseparable from the environment. But masks, self-portraits and mirrors are also frequently cited, as if the women participants are coming to see themselves, and to see themselves differently through the process of exchange. A mask might attest to the casting off of an identity, a self-portrait to the process of seeking recognition from another, and the mirror to an invitation to reflect on oneself.

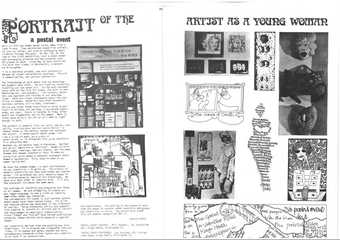

Fig.2

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman: a postal event

Page spread reproduced from MAMA: Women Artists Together, c.1978, pp.24–25. Lyn Austin’s Bubble Bath Suicide is pictured at the top of p.25, second from right

Courtesy of Su Richardson

This focus on the self through interaction with others in the Postal Art Event connects with consciousness-raising and the process of subject formation in the act of telling one’s story and having it heard by another. In this way the Postal Art Event corresponded with the process of coming together in London/LA Lab. While the collaborations in the former were mediated by material objects, the artists in the latter came together through difference and thus came to know each other as mediated by their performance work and the shared experience of being in a different city. In both cases the act of coming together was integral to the realisation of the artworks: connections were formed between artists and contributed to a larger infrastructure produced entirely through the artists’ collaboration. This infrastructure might also be described as an exhibition, but unlike the static scenes usually associated with exhibitions, these projects depended on duration and the activation of spaces, people and communities across time.15 As such the realisation of art and the artist did not rely on entry into or validation by an institution but was itself wound back into the process of making – making the artwork, making the artist and making the self.

Sharing stories led to a particular kind of collaboration, whether in the context of the consciousness-raising circle, the postal art object or the performance. This process relied on the participants opening up to one another by trespassing architectural, geographic, conceptual and bodily limits. Feminist theorists including Adriana Cavarero and Jessica Benjamin have differentiated this process of relating from the self-reflection guided by the analyst in Freudian psychoanalysis.16 Unlike the emphasis on the internal and the excavation of causes of neurosis within the subject’s unconscious through the talking cure, consciousness-raising focused on the external and sought to mine the material causes for women’s psychic, professional and domestic oppression. Some feminists were careful to distinguish consciousness-raising from ‘group therapy’ to emphasise its importance as a tool for political organising.17 Others aligned it to the process of ‘speaking bitterness’, a form of organising associated with leftist politics, particularly in relation to Maoist China.18 Yet however the process was described, it facilitated a way for women to be together, to exchange ideas and ultimately to combine an exploration of both the internal and external factors informing their oppression. This was also evident in the Postal Art Event as the contributors addressed both participants’ feelings of isolation in the home in relation to its physical limits. One example is a tray-like box relief divided into segments and filled with text pieces and ephemera, which reads at the top: ‘I wonder what it’s like to be in your kitchen, your mind, your place’ (fig.2). Indeed, like consciousness-raising, the Postal Art Event not only analysed these conditions but also challenged them, as the circulating objects trespassed the boundaries of the home. This activity contributed to a counter-economy, as the women exchanged the art objects as gifts or tokens of affection and connection, arguably establishing an alternative public sphere.

The process of collaborating on the Postal Art Event also entailed a radical reformulation of the art object itself. Objects were often ad hoc and made quickly, which is not to say that they were not also expedient and exact. For instance, a box of Black Magic chocolates, empty of confectionery, was refilled with modelled body parts including breasts, arms, legs and a large toothy grin (fig.1). The work posed the body as ripe for consumption: perhaps referring to romantic fulfilment, as suggested by the symbolism of the box of chocolates as a love token, as well as the violent fragmentation of the body into discrete parts more easily taken in by the eroticising – or exoticising given the brand of chocolates – gaze.19 Art and daily life collide in these works, but the crummy materials, dark humour and focus on restriction and boredom represent an everyday experience usually invisible in the bravura and roughness of assemblage or the colour, gloss and scale of pop art.20 The shared motifs also tested the terms of originality as ideas would emerge and re-emerge across work or when different women intentionally picked up the same theme. For example, the fear and desperation proposed in the upturned body set in toxic polystyrene foam spilling over the sides of a model bathtub in Lyn Austin’s Bubble Bath Suicide (fig.2) was relieved in the equation of the bath as a space of one’s own in the shoe-box enclosed Sanctuary, whose maker is unattributed (fig.1).21 In this way the Postal Art Event provided the site for images and ideas to be gleaned and reworked, as well as for artists to provoke one another’s work. The conceptual boundaries between each piece were porous and the actual object mobile. As a result the participants’ relationship to their works was less direct. The process of sending it through the post not only transferred ownership, but was also meant as an inspiration as well as a channel for emotional, affective responses.

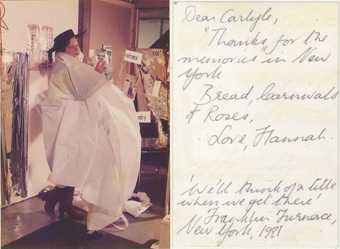

Fig.3

Photograph of Leslie Labowitz, Suzanne Lacy and Carlyle Reedy at Franklin Furnace, 1981

Collection of the Women’s Art Library, Goldsmiths, University of London

Photo: Hannah O’Shea

Courtesy Hannah O’Shea

The artists in London/LA Lab were similarly open to exchange and overlap, although the degree to which the works shown were directly impacted was uneven and is now hard to trace. However, the trip certainly provided an impetus for the artists to develop their work: Tina Keane, for instance, incorporated material filmed while in New York – including footage of the performance group Disband, which counted Franklin Furnace founder Martha Wilson as a member – into a work called Hey Mack 1981.22 While some of the works performed or screened during that fortnight in New York were complete before the artists arrived (such as Sally Potter’s contribution) and many showed film and video work (Keane, Nancy Buchanan, Cheryl Gaulke, Judith Higginbottom, Leslie Labowitz, Linda Montano, Sharon M. Morris, Hannah O’Shea, Sally Potter, Martha Rosler, Barbara Smith, Nina Sobel and Chris Swayne), other pieces were in flux and responded to the performance sites and the unknown city. Perhaps most crucially, the event allowed many of these artists to interact over an extended period of time and the traces of these encounters to persist in other works, projects and documentation.

London/LA Lab was curated by the Los Angeles-based artist Suzanne Lacy and the London-based artist Susan Hiller, but was initiated by New York-based Martha Wilson. Wilson proposed the idea in 1980 when Hiller was visiting New York to see the exhibition British Art Now: An American View selected by Diane Waldman at the Guggenheim Museum.23 Hiller and Wilson were both disappointed by the absence of women artists in that exhibition, as well as the institutionally legitimised story of British art – primarily associated with post-conceptualism – that it told. Despite the decade of political activism and protest with which many artists had engaged in 1970s Britain, all of the participants were represented by well-established commercial galleries. In response to this anodyne display, Wilson offered a space to Hiller in the programme at Franklin Furnace, an exhibition space and archive she had established in 1976 for the preservation and commissioning of performance art. Suzanne Lacy was then invited to select Los Angeles-based artists, expanding the idea of the exhibition into a kind of meeting place. The addition of this third city countered any attempt to define women’s art on national terms, or to advocate for a coherent national identity (fig.3). Indeed, the artists were only ever described as ‘based’ in their respective cities and many were born or had worked in different places, while a number of the London artists – including Hiller – were in fact American.24

London/LA Lab placed fixed understandings of national identity or belonging to the side, although there was an element of curiosity in bringing together different artists and understanding what made them different.25 At this point in their careers none of the artists had international or transatlantic reputations and most had no institutional or commercial support to fund exhibitions or travel. Whereas other transatlantic exhibitions of women’s and political art had taken place throughout the 1970s, none focused on live art as London/LA Lab did.26 Of course this kind of practice depended on the presence of the artist, but also on the surroundings in which it took place. Each performance or presentation had to be adapted to the specific context despite the fact that many artists contributed an iteration of an earlier work. Hannah O’Shea sang her Litany for Women Artists in a different acoustic setting, Leslie Labowitz set up her Sproutime environment and fed the results to the gathered viewers and Rose Finn-Kelcey performed Mind the Gap in a phonic environment in which the commonplace British phrase did not translate. This contingency undermined the stability of the work and its relationship to either London or Los Angeles, yet neither did it become specific to New York. The effect was an uprooted, mutable space in the shape of an art exhibition or performance programme, which provided a site for women to come together to share their work. London/LA Lab also broke down stable identities, exploring potential relationships across differences that were the result of varied experiences unfolding in distant places. Here the collaborative environment provided a temporary intimacy that paralleled the process of exchange in the consciousness-raising circle.

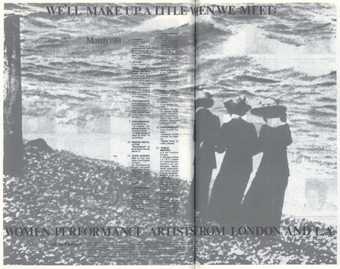

Fig.4

Advert for We’ll Make Up a Title When We Meet, London/LA Lab, from an artists book accompanying the performance Mounting by artists Rose English, Jacky Lansley and Sally Potter at Modern Art Oxford, 1977

The experimental conditions of the project are summed up in its title, London/LA Lab, but its contingency was even more evident in the earlier, working title, We’ll Make Up a Title When We Meet. This title featured on Franklin Furnace’s in-house broadsheet publication, the Flue, and the project poster, which took a still from one of Lacy’s performances as its background.27 The still depicted three women in late-nineteenth-century dress walking huddled together, along a shoreline (fig.4). Their looped arms suggest mutual support as they navigate a rough terrain – gesturing to a longer history of women’s interaction, as well as to the possibility that such encounters were ongoing, specifically in the New York programme. This corresponded to the desire to make London/LA Lab a ‘forum open to the public’, which could create a place where the artists could ‘perform individually and collaboratively’ while occupying the gallery spaces at Franklin Furnace, Just Above Midtown and 626 Bway. Indeed, the development of a discursive space was secured by inviting an art critic from London, Caryn Faure Walker, and one from Los Angeles, Moira Roth, to document the project and contribute to the discussion.28 As such, the atmosphere was open-ended and responsive, creating a place to share artworks as well as one for reflection and discussion.

There was, however, a degree of disagreement between participants, with divides following the fault line of nationality.29 While Lacy and the Los Angeles artists saw the event as the beginning of a long-lasting collaboration, the London-based women were reluctant to open up. This discord appears to have been sparked from the differences between the ways in which the artists worked, as well as the difficulties they felt in coming together and understanding one another, a point reflected in the reviews accompanying the programme. To some extent this challenges a reading of the event as collaborative, but really it invites a more sensitive understanding of collaboration, which supports fallouts and failures, as well as agreement and communalism. In relation to artistic practice, the collaboration entailed in London/LA Lab – like that in the Postal Art Event – was not concerned with co-production, but with putting on the figure of the individual artist by creating new ways to share and disseminate artworks. It also gestures to a shift in the status of the artwork toward a material that might mediate relationships between artists as well as those between artists and viewers.

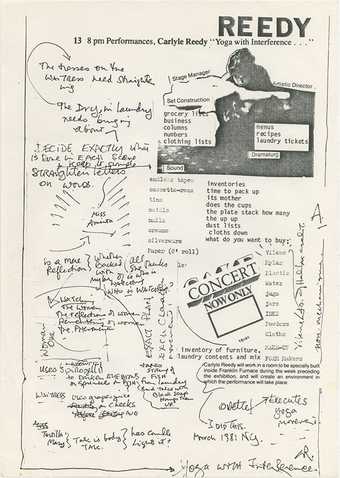

Fig.5

Documentation of the performance Yoga with Interference by Carlyle Reedy as part of We’ll Make Up a Title When We Meet, LA/London Lab at Franklin Furnace, New York 1981

Photo: Hannah O’Shea

Image courtesy of Carlyle Reedy

Carlyle Reedy’s performance Yoga with Interference (fig.5) was particularly concerned with mediation and the difficulty of representing oneself. Reedy’s piece developed from a performance that she had shown a year earlier in London, which included seven women performing different roles in a set complete with a ‘bed’ made up of sheets on the floor and a projection behind.30 In this work Reedy performed as her character Miss-a-minta, with a wide, over-bearing paper cloak that consumed her body and restricted her gestures. Miss-a-minta appeared again in London/LA Lab, another character among others, this time all played by Reedy. The artist has written of the performance:

Yoga with Interference was very coherently an exposure of women’s capacities, taking various women. They were all the one behind the screen who was trying to get on with her yoga. And the first one was ‘numbers woman’. She was involved in lists of groceries, schools schedules, Christmas lists, book lists, lists of all the things that women have to do in slavery of domestic life.31

Each of these characters became ciphers for different ‘facets’ of Reedy’s or her mother’s experiences, which emerged as the artist went back and forth behind a screen.32 Each facet presented a different obsession or fixation that interfered with thought, symbolised in the performance by the concentration demanded in yogic meditation. The effect was a representation of the singular subject in a process of fragmentation.

Reedy’s use of personal experiences instrumentalised the process of sharing stories as a performance. The twist was that the plural stories originated in the singular one woman, as a series of conflicting demands and desires.33 This had the effect of breaking down the feminist fiction of homogenous womanhood, but also of exposing the psychic effect of images, stories and expectations that surrounded and impinged on every woman’s life. While many of the facets related to the multiple roles women play in their lives, some were more specific, referring to other women, as if they had entered into Reedy’s unconscious. As she states: ‘I would say that none of the roles were acted. They were mostly derived from either my mother’s or my own or women I knew, their experience … I knew all of these things in myself, so they were not acted.’34

Yoga with Interference parallels the consciousness-raising process, staging the work of self-reflection and critique. It contrasts with other feminist-influenced performances that borrowed the form of consciousness-raising by encouraging participation, or that used stories gleaned from the process as a prompt for artworks. This kind of practice had roots in California and the feminist art programme established by Judy Chicago at Fresno State College in 1970, but for Lacy, who had been a student on Chicago’s programme, ‘support, feedback and evaluation’ were the ‘cornerstone[s] of feminist art’ that characterised the work of artists on the West Coast.35 While this way of working – exemplified by Cheri Gaulke’s Broken Shoes in London/LA Lab – sought to expand the consciousness-raising circle through performance, Reedy’s work, and that of many of the London-based artists, explored the possibilities of self-presentation and representation.36 This is evident in Reedy’s distinction in this passage between acting and performing. Yoga with Interference did not incorporate the voices of other women, or build characters from the facets; rather, it channelled multiple experiences as if embodying a cacophony of voices, echoing through Reedy’s own experience of performing, rather than acting, the role of woman.37 As such, the everyday performance of womanhood was mediated by the context of the art performance, with the circulation of facets gestured to by labels attached to lengths of string that looped the room. Like intersecting telephone lines the confusion of wires created a chaotic environment, a visual analogue for the cacophony of characters rehearsed in the performance.38 In this way, Yoga with Interference entailed sharing stories, with Reedy as a conduit or spiritual medium, revivifying lost voices and suggesting an alternative but evocative understanding of mediated collaboration.

In the larger framework of London/LA Lab, Yoga with Interference was one story among others, all of which were performed rather than ‘told’ as an interrogation of the characters women played, the perspectives they were offered and the roles they occupied. Each performance pushed against the confines of those formal devices, with the durational nature of the three-week series meaning that other interactions between women could emerge. In this sense London/LA Lab fostered a site for the sharing of work and for collaboration without a final object or outcome in mind. Like consciousness-raising it was concerned with process and, through communication and interaction, finding new ways to relate. As Margia Kramer has recalled of an encounter with Reedy at Magoo’s Bar after the performance: ‘We talk about the personal and just the other side of the personal – about her work and mine.’39

Art (and) work

One effect of collaborative practice for women artists in the 1970s was that it created the space and time for women to work. For the women of the Postal Art Event this meant finding space and time among a tide of other responsibilities, whereas the artists in London/LA Lab took time out and travelled to a foreign space to delineate a concentrated period for working together. The kind of imaginary community mobilised in the former was realised physically, if only temporarily, in the latter. The 1981 project meant that women could put aside other responsibilities and material limitations to create a unique space for art practice to take place. This marks a shift from the fixed space of the consciousness-raising group and the process of sharing stories to the more contingent space of these art projects and the experience of working together. Reedy attests to this in her account:

It was wonderful because at Franklin Furnace I had a workspace which I always needed, so I prepared everything there. Everything. The whole shambolic scenario was prepared there in the company of some wonderful women, who also did unexpected things. It’s impossible to be only centred on your own work. In a sense you do, while you’re there, keep your focus, of course.40

Reedy occupied the office space at Franklin Furnace and like the artists of the Postal Art Event she used surrounding materials to pause the usual routines of work and make space for art. The photographs, printed text and string that contributed to Reedy’s performance environment resembled those found in the archives at Franklin Furnace, although here they were not ordered and filed away but spun out, chaotically criss-crossing the room in a ‘shambolic scenario’. In addition to this, the three-dimensional room-scale collage also comprised large swathes of silver foil paralleling the improvised glamour of Reedy’s Miss-a-minta costume. The photographic documentation of the performance shows the silver Mylar, like culinary tin foil, hanging from the walls in jagged folds, with some sections still semi-rolled. In this way Yoga with Interference collided the home and the office, demonstrating that they were not independent, divided spheres but continuous sites demanding different aspects of feminine performance.

Fig.6

Handout from the performance Yoga with Interference by Carlyle Reedy as part of We’ll Make Up a Title When We Meet, London/LA Lab at Franklin Furnace, New York 1981

Image courtesy of Carlyle Reedy

Reedy’s handout for the performance spelled out this collision of spaces and their attendant responsibilities further (fig.6). The single sheet was a collaged combination of printed, type- and handwritten texts. The page included a printed description of the performance, an image of Reedy in the top right corner, typewritten lists that corresponded to both domestic tasks and the materials needed for the performance – a far more instrumentalised version of the common conceptual art form – as well as notes, scrawled across the surface, relating to the performance. The notes list the costumes for each character and reminders such as ‘DECIDE EXACTLY what is done in each scene + keep it simple’. This handout made the process of producing the piece an integral part of the performance, as well as functioning like a programme helping the viewer to interpret the characters and events. Following the conventions of a programme, the handout also included credits, yet instead of listing names beside the tasks, including stage manager, artistic director, set construction, sound and dramaturgy, the roles were printed like labels that ringed the image of Reedy working, along with two other lists of tasks. Just as the performance presented facets of women’s existence through the figures of the ‘waitress’, ‘Tortilla Mary’ and the ‘Numbers Woman’, the handout textually represented the cacophonous buzz that the woman (artist) had to manage or, in this case, channel.

The objects produced in Postal Art Event also revealed the multiple roles and responsibilities that weighed heavily on the housewife and, like Reedy’s performance, made everyday materials the subject of artwork. The circulation of these ephemeral objects was also crucial for resisting the often overwhelming flood of paid and unpaid work many housewives faced in the 1970s. They could be made in the moments between other tasks – the ‘commas of time’ as some feminist groups described them – half-finished objects and crochet needles put down and picked up again, as Su Richardson suggested.41 In their re-use of domestic detritus, the participants of the Postal Art Event threw a spanner in the continuous routines of household labour, finding time for reflection and critique in the wake of that ever-turning tide. Furthermore, the recirculation of those obsolete materials in the form of art objects broke the isolation of the home and provoked solidarity between women from the inside by corrupting the circuits of domestic administration, care and production. In equal measure the Postal Art Event was an attack on the limitations of home and the autonomous artwork.

The Postal Art Event’s double confrontation of housework and artwork might also be read as a merging of the roles of housewife and artist. The project framed art practice as an activity to be worked at alongside other responsibilities. The objects of the Postal Art Event explored and attested to the possibility of an artist working part-time through both content and form. The demonstration of the artist as housewife in the Postal Art Event corresponds with work by artists including Bobby Baker, Martha Rosler, Silvia Ziraneck and perhaps most famously Mierle Laderman Ukeles.42 Unlike these performance works, the artists of the Postal Art Event made work as housewives, without staging their domestic labour as the subject of the artwork. This difference highlights two things. Firstly, whereas performances like Laderman Ukeles’s Hartford Wash 1973 or video works like Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen 1975 played the habitual and systematic form of domestic labour off against the expressive and open work of the artists, the participants in the Postal Art Event fitted their art practice around other tasks. Secondly, in her series of performances at the Hartford Atheneum in Connecticut, Laderman Ukeles made maintenance labour the work of the artist, foregrounding how this kind of work was devalued in relation to art through its invisibility in the home and behind the scenes of the institution.43 In contrast to Laderman Ukeles’s occupation of the museum (originally she had intended to live in the gallery with her husband and child), the Postal Art Event artists looked to each other to create an alternative audience for their artworks. The home and the labour of housework manifested itself differently in this project as the artists defined a new sphere of reflection by working together, rather than disrupting the sites and spaces of the art world with embodied performances of their domestic labour. Their collaborative correspondence network established a ‘new and other community’, as Kokoli has argued, delineating a contingent but separate space for feminist critique.44

The sense of community invoked in the Postal Art Event challenged the organisation of artistic relationships and art production around homosocial competition, the terms of which Griselda Pollock has analysed and unpacked.45 Particular artists, artworks or stylistic motifs were not presented as a means of moving art onwards and overcoming the past; instead materials, ideas and formal propositions became the substance of mediated collaborations. In these worlds, artistic identities were not imbued with mythologies of bohemianism or bravura that had individualism as a common conceit. The artists responded to each other and the material conditions around them without regard to medium or translation from the everyday into an art world context. Instead, these objects transformed the everyday. The avoidance of artistic precedents and the art market in this project might be compared to the circulation of postcards and text works in other mail art projects in the 1970s.46 However, unlike those objects – which often passed between artists accruing markers of their identities with signatures, stamps and monikers – the relationships between women in the Postal Art Event were less about asserting the presence of particular artists than engaging each other as women and artists. This is demonstrated well by Su Richardson’s series of crochet ‘ME’ panels, which comprise this two-letter text in block capitals stretched to fit small, framed expanses. Unlike the assertion of the artistic ‘I’, this work seems to demand a moment for self-reflection, which Richardson described as ‘just something I made for myself’.47

…If you show me yours: representing the collaboration

This article has discussed how collaboration functioned for women artists as an expression of feminist politics, as well as how it contributed to delineating an alternative framework for artists to come together beyond the other roles they performed as housewives, mothers and wage labourers. However, collaboration was not only crucial for fostering relationships between women: it was also important for representing coalitions between women and the presence of feminist communities nationally and internationally.

While work by women artists featured in magazines, journals and newsletters through reproduction and description, both the Postal Art Event and London/LA Lab highlight the importance of exhibition organising for women artists. Rather than read these exhibitions as indications of the artists’ desire to court art world legitimation, the exposure of both projects to an exhibition-visiting public meant the expansion of their collaborative constituencies. This was the underlying intention of London/LA Lab as it brought together women based in different cities, mobilising a temporary feminist community – to borrow from Kokoli’s discussion of the Postal Art Event – with members from London, Los Angeles and New York. It was also evident in exhibitions of the Postal Art Event, which took place in Manchester, Liverpool, Sheffield, Edinburgh, Birmingham and London. These shows expanded the parameters of the project and resulted in the accumulation of new contributors. The ambition of these projects reflected those political ambitions of second-wave feminism as well as its formal organisation as an international, decentralised movement. These artworks not only borrowed the model of the consciousness-raising group but also constituted an alternative, if contingent, community, representing that community through exhibitions that placed works in dialogue. London/LA Lab mobilised interactions between artworks, artists and audience members through their programme, but the Postal Art Event exhibitions also developed innovative displays that brought the objects together in mise-en-scènes resembling domestic interiors.48 These installations grew in scale and saturation with each display as the objects produced for the exchange accumulated. The result was a representation of feminist collaboration, which was both powerful and empowering.

Despite the ideal of community evident in both the Postal Art Event and London/LA Lab, neither project collapsed the different artists into a single collective of women. Instead they activated and represented an open-ended and continuous conversation unlimited by spatial, institutional or geographic bounds although frequently marked by racial blindness. In fact, the projects were both animated by antagonism and solidarity. The fall-out concerning an appropriate title for the 1977 exhibition of the Postal Art Event at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London, highlights differences between those who identified as ‘housewives’ or ‘young women’.49 There were also numerous points of conflict between the women involved in London/LA Lab. This extended from the artists’ different investments in the project or in the opportunity to visit New York, as well as mistranslations between American and British and East and West Coast artists. On the one hand these instances show up the banal and commonplace difficulties that accompany all forms of working together, which are certainly not exclusive to women. On the other, they demonstrate the shifting dynamics between individual subjects and the group, between identification and self-reflection, which mirrored the process of consciousness-raising and characterised feminist organising.

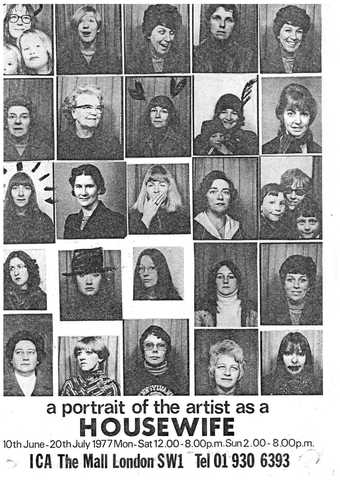

Fig.7

Feministo: Postal Art Event, ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Housewife’, exhibition poster, 1977

Courtesy of Su Richardson

This point is well illustrated by advertising materials for both projects: the first a poster for the Portrait of the Artist as a Housewife exhibition at the ICA; the second the pull-out from the issue of the Flue featuring London/LA Lab. Both of these used the motif of a grid to illustrate how these individual artists came together collectively. Although the grid is more obvious in the Postal Art Event poster, it is also evident in the Flue feature, perhaps rendered more so by the comparison. The point is a simple one: the photographic grid provided a way for the numerous artists, usually separated by geographical distance, to come together on a single surface, while gesturing to their separation and distinction. These differences are emphasised in both examples by the consistency of the image format: the recognisable square shape of the photo booth portrait in the former and small circular porthole profiles in the latter. Within the square and circle frames, the women played with representation, winking, blinking, sticking their tongues out, dressing up, posing with children or absenting themselves from the frame entirely. Although these collaborative projects represent small, limited constituencies of women artists, their two photo-grids demonstrate the desire to disrupt a stable category of the ‘woman artist’ and assert the importance of the individual voice raised in a collective chorus. The visual representation of this collectivity became another material artefact to circulate. Richardson’s copy of the poster (fig.7), for instance, has inked-on doodled annotations: Monica Ross, the artist’s close friend, has a Robin Hood-style hat, while another woman has her teeth blacked out and another has lines extending from her head to signify her radiance. This poster, like the playful poses of the London/LA Lab pull-out, not only represents the collective visually; it demonstrates the intimacy between the women participants, suggesting the ways in which collaboration and sharing artworks could be as politically affective as consciousness-raising.