In the second half of the eighteenth century, buoyed by a decisive victory at the Battle of Plassey (1757) in Bengal, the East India Company sought to consolidate its interests across India through a carefully calibrated combination of military and diplomatic activity. Spanning a period of thirty-three years between 1766 and 1799, the Anglo-Mysore Wars were among the most protracted and significant of Britain’s numerous imperial campaigns. Fought across the peninsula of south India, the four wars led to the ultimate overthrow of the Kingdom of Mysore (ruled by Hyder Ali until 1782, and subsequently by his son, Tipu Sultan) by the East India Company and its allies, but not before considerable British humiliation in the second Anglo-Mysore War of 1780–4. Although often played out across the same landscapes, the four wars were markedly different conflicts which required appropriately differentiated representational strategies from the narratives which described them. Indeed, a vast body of visual and textual material was published in relation to the landscape and the British experiences of the Anglo‑Mysore Wars, from maps and views to journals and histories, almost all of these produced by employees of the East India Company, and offering varying degrees of official and personal testimony. Many of these publications took the form of pictorial and textual tours of the Kingdom of Mysore, focusing heavily on hill forts, tombs and memorials. These accounts and representations generated complex narratives of the colonial landscape which were shaped not only by military encounter and political strategy, but also by aesthetic processes and by personal and collective memories. Indeed, published and actual tours of south India were shaped by overlapping strategies that served to record and represent the landscape not merely as a space in which the East India Company was successfully establishing its presence, but also as one in which individuals sought to inscribe experience and memory in the aftermath of a protracted and often traumatic series of wars. As the geographer Karen Till has noted:

places are never merely backdrops for action or containers for the past. They are fluid mosaics and moments of memory, matter, metaphor, scene, and experience that create and mediate social spaces and temporalities. Through place making, people mark social spaces as haunted sites where they can return, make contact with their loss, contain unwanted presences, or confront past injustices.1

Till is writing about a city (Berlin) rather than a landscape, but the processes she describes can nonetheless be discerned within the pictorial and textual narratives that articulate the landmarks and experiences of the Anglo-Mysore Wars. These narratives articulated place as a formative and highly experiential aspect of war, where memory could subsequently be located and invoked. They did not simply set out to construct an historical landscape – one that blurs the academic boundaries between landscape and history painting – but rather to engage an on-going and subjective process of collective memory. Here it is useful to consider the distinction between history and memory proffered by the French historian Pierre Nora:

Memory is life, always embodied in living societies and as such in permanent evolution, subject to the dialectic of remembering and forgetting, unconscious of the distortions to which it is subject, vulnerable in various ways to appropriation and manipulation, and capable of lying dormant for long periods only to be suddenly reawakened. History, on the other hand, is the reconstruction, always problematic and incomplete, of what is no longer. Memory is always a phenomenon of the present, a bond tying us to the eternal present; history is a representation of the past … [H]istory belongs to everyone and to no one and therefore has a universal vocation. Memory is rooted in the concrete: in space, gesture, image, and object.2

Nora’s argument posits not merely a distinction but an opposition between history and memory, structured across a binary of death and life, where the inert, contained and universal finality of history operates as the antithesis of the volatile and plural continuity of memory. This is a helpful framework for understanding some of the processes and imagery which will be explored in this article, but it is nonetheless the case that the complex intertwining of strategies and concerns within these works means that histories and memories are, at times, constructed simultaneously, even if they are maintained as discrete strands of textual and visual practice. Representations of the landscape of the Anglo-Mysore Wars were structured through complex aesthetic processes which intertwined experience, memory and death with strategies of imperial control that were reliant on more objective processes of historical and geographical knowledge. Collectively, these works assert the value of the landscape and its distinguishing features as registers of loss as well as acquisition, of experience and memory as well as of information and history.

The most distinctly visual of the published tours of the Kingdom of Mysore were four sets of views produced in the aftermath of the third Anglo‑Mysore War: Robert Home’s Select Views in the Mysore, the Country of Tippoo Sultan; from Drawings Taken on the Spot by Mr Home, with Historical Descriptions (1794); Robert Colebrooke’s Twelve Views of Places in the Kingdom of Mysore (1794); Alexander Allan’s Views in the Mysore Country (1794); and James Hunter’s Picturesque Scenery in the Kingdom of Mysore (published in 1804 using drawings made by Hunter prior to 1792).3 These adopted varied but closely related means of representing the landscape of the region. Home’s and Colebrooke’s publications, for example, juxtaposed image and text, while Allan’s and Hunter’s consisted solely of views. Crucial to all four publications, however, was the authentication of the views having been taken ‘on the spot’ – a claim which appears in the title or preliminaries of Home’s, Colebrooke’s and Hunter’s series, while in Allan’s scenes the frequent inclusion of officers and soldiers testifies to his presence in the landscape. Additionally, Allan’s, Colebrooke’s and Hunter’s drawings were reproduced in aquatint, a technique able to convincingly replicate the media of watercolour and of pen and wash drawing that were typically used by military draughtsmen when they produced fair copies of sketches made in the field.4

Joseph Mallord William Turner

The Siege of Seringapatam

(c.1800)

Tate

Published in Britain at a time of heightened patriotic interest in Britain’s imperial, military and economic status, these works generated both geographical and imaginative familiarity with the Kingdom of Mysore. Around 1800 J.M.W. Turner produced a number of works in watercolour relating to the conclusion of the Anglo-Mysore Wars at Seringapatam. There are two such works in the Tate collection, The Siege of Seringapatam c.1800 (fig.1) and Study of the Fortifications of Seringapatam ?c.1801, which was the basis for a watercolour depicting Cullaly Deedy, the water-gate at which Tipu Sultan, ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore, had resided during the siege (fig.2). Representing scenes from during and after the battle, these watercolours articulate a highly specific landscape, one whose physical features are crucial to the experience and recollection of war, and within which history and memory are carefully structured. The finished watercolour of Cullaly Deedy adopts a more distant viewpoint than the colour study on which it is based, and places in the foreground a reclining soldier who gazes at the fort from a position of detached reflection. The battle scene, meanwhile, even in the midst of action, inscribes its conclusion into the landscape – in the background, silhouetted against the sky, and emerging through the smoke of gunfire, are the vertical projections of the Sri Ranganathaswami temple, the Jama Masjid, and a flagstaff from which the British flag is flying. Here the strict topography of the fort has been reconfigured to allow these three sites to be articulated in a sequential arrangement that presents Hindu, Muslim and British presences in the landscape as markers and assertions of successive regimes of power. Another watercolour, depicting Hoollay Deedy (fig.3), the site within the inner rampart of the fort where Tipu Sultan was killed, locates the memory of death within the physical fabric of the fort, registering the absence of an individual through the presence of a landmark.5 Based on a watercolour made in situ by Thomas Sydenham, a captain in the Madras Army, Turner’s watercolour adapts the somewhat ramshackle features of the fort that are evident in Sydenham’s sketch, in particular the gateway itself, which is rendered by Turner as a whiter, more ornamental and neoclassical structure, fitting to its status as a memorial in the landscape.6

Fig.2

J.M.W. Turner

Cullaly Deedy, Water-Gate in the Outer-Rampart of Seringapatam, where Tippoo Sultaun Resided during the Siege c.1800

Graphite and watercolour on paper

Private collection

Fig.3

J.M.W. Turner

Hoollay Deedy, or new Sally-Port in the Inner Rampart of Seringapatam, where Tippoo Sultaun was Killed, on the 4th May 1799 c.1800

Graphite, watercolour, scraping out and bodycolour on paper

Clark Institute, Williamstown, Mass.

These works, which were only attributed to Turner in the 1980s, are unusual within the artist’s oeuvre, focused as they are upon a location which he never actually visited.7 Although still at an early stage of his career, Turner had, by 1800, already established his sketching tours as a vital part of his artistic practice, and was reportedly prone to talking of ‘nothing but his drawing, and of the places to which he should go for sketching’.8 Turner’s watercolours depicting Seringapatam are anomalous for their indirect encounter with the landscape represented – they relied to a significant degree upon the experiences of those, such as Sydenham and other military draughtsmen, who had encountered these locations in the course of the various campaigns of the Anglo-Mysore Wars. With the exception of Home, who due to restrictions imposed by the East India Company’s Court of Directors was the only professional artist permitted to accompany the Governor-General, Lord Cornwallis, and his army for any part of this campaign, the draughtsmen whose drawings were the basis for the engravings and aquatints that appeared in the published pictorial tours of southern India served as officers in the third Anglo-Mysore War: Hunter and Colebrooke were lieutenants in the Royal Artillery and Bengal Infantry respectively, and Allan was a captain in the Madras Army (both Colebrooke and Allan were deployed as surveyors, while Hunter’s drawings were produced in a more amateur capacity).9 However, distinctions between ‘professional’ and ‘amateur’ artists are somewhat unsatisfactory when used in relation to the kinds of works, practices and individuals under discussion here. It is worth noting that instruction in drawing formed a crucial part of the syllabus at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, which hired two drawing masters to instruct ‘gentleman cadets’ in the rudiments of topographical drawing for over sixteen to twenty hours each week.10 The curriculum covered architecture and ‘military embellishments’ as well as landscape and perspective, and instructed the cadets in the handling of pencil, ink and watercolour. The chief drawing master at the Woolwich academy was the artist Paul Sandby, who in 1768 (the same year that he was appointed to this post) was made a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts.11 It is likely that Allan and Colebrooke were taught by Sandby, who was a highly accomplished topographical draughtsman.12 They would have received – by virtue of the structured curriculum at the Woolwich academy – more direct tuition from a Royal Academician than was actually the case for students of the Royal Academy itself, where teaching was reportedly inconsistent and provided along somewhat laissez-faire principles (and, indeed, was arguably of little benefit to a student who aspired to landscape painting as a specialism).13 Moreover, since draughtsmanship was considered to be a polite social accomplishment, many cadets – who were invariably from families of wealthy means – would have received instruction outside the academy from professional artists in order to develop their proficiencies in drawing landscapes in ways which moved beyond the surveying and cartographic modes that were taught at Woolwich.14 The education, training and accomplishments of officers therefore overlapped considerably, so that an activity such as draughtsmanship may be regarded as a site in which social, aesthetic and professional practices became intertwined – something which will become apparent from looking at the imagery produced by officers during the Anglo-Mysore Wars.

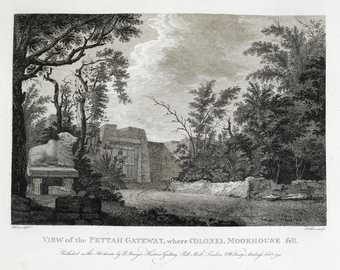

Representations of the landscape of the war zone, therefore, became more than straightforward records of battle or surveys of land. Rather they brought together the experiences and memories of war within pictorial frameworks that demonstrated the gentleman-officer’s familiarity with art and aesthetics as much as his knowledge of the colonial territory. While accompanying Lord Cornwallis’s Grand Army, Robert Home drew the gateway of the pettah (or native town) at Bangalore with a view to producing two kinds of imagery, first an engraving for the Select Views in Mysore (fig.4), and secondly a large history painting, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1797, of The Death of Colonel James Moorhouse at the Storming of the Pettah Gate of Bangalore (National Army Museum, London). Although the painting visualises in frankly religious terms the patriotic martyrdom of Colonel James Moorhouse during the third Anglo-Mysore War, both images serve a commemorative function in relation to Moorhouse’s heroic death. Indeed the absence of Moorhouse from the engraved landscape image renders the image acutely poignant and elegiac. The gateway functions as a kind of architectural memorial complementary to the sculptural one erected ‘by order of the Court of Directors of the East India Company’ in the church of St Mary, Madras, where Moorhouse was finally buried.15 Notably, the inscription on the St Mary’s memorial is very specific, not only as to its commissioning, but also with regard to the location of Moorhouse’s death, recording that the officer was killed at the ‘pettah gate of Bangalore’. With its own engraved inscription and accompanying text invoking the memory of Moorhouse in much the same way as that on the sculpted memorial, Home’s print serves to transform the scene of Moorhouse’s death into a space of historical commemoration, and to memorialise the dead hero through an act of topographical recognition and association. Here, unlike the painting and the sculpted memorial with its medallion portrait of Moorhouse, a poetic absence is registered and acutely marked within the engraving’s landscape, which serves as a timeless memorial to the British hero. Reading the landscape for traces left by deceased individuals became an important aspect of pictorial and actual tours of the region which were taken in the aftermath of war. In 1800, Charlotte Clive, touring south India with her mother and sister, recorded in her journal the occasion of their visit to Vellore Fort to see the breach in the wall made during the 1751 siege by her grandfather, Lord Robert Clive, the former Governor of Bengal.16 In visiting this site, the Clive women attempted to scan the landscape for the scars of battle that informed their illustrious family history, with Charlotte’s mother, Henrietta, recording that she ‘was determined to see as much as [she] could for a place so remarkable in the annals of this family’.17 The landscape held a personal and familial significance for the Clive women that persisted across the distance of time, and was able to supply memory and counteract familial absence. But, like the pictorial tours produced by Home and others, the Clive women’s tour also delineated more recent military history in identifying and visiting the locations that had played a crucial part in the subsequent campaigns in the Mysore region, allowing them to comprehend the experiences of individuals by encountering the landscape itself. At Seringapatam, the party paused to see not only the gate where Tipu had finally been vanquished (fig.3) but also the marks of his blood on its surface, once again equating the spaces of war with the physical traces of its key players and events.18 If Turner, in his watercolour, whitewashed out the traces of battle from the gateway that Thomas Sydenham had drawn for him, he did so in a way that was complementary to Henrietta Clive’s instinct to recognise the site as a register of a significant individual.

Fig.4

Robert Home

View of the Pettah Gateway where Colonel Moorhouse Fell engraved by James Fittler 1793

Etching on paper

Copyright © The British Library Board

Death and commemoration structure Robert Home’s tour through the Kingdom of Mysore which, as literary historian Mary A. Favret has shown, was a landscape ravaged by the destruction of war.19 What is notable, however, is the way in which Home’s imagery moves from the specific to the general – from the commemoration of one fallen hero to that of many. In a scene representing, for example, a burial ground for British officers at Bangalore (fig.5) Home’s imagery makes a crucial transition from drawing to engraving. In Home’s drawing, the inscriptions on the tombs identify them as belonging to, and hence commemorating, individual officers.20 But when the engraving was produced, the inscriptions were removed from the tomb and placed overleaf, rendering the monuments eerily void. This erasure – and the detachment of the inscriptions to a page which is not visible when the print is viewed – transforms the burial ground from the resting place of seven named officers who died in the third of the Anglo-Mysore Wars to a less specific grouping of monuments which can be taken to serve as memorials to all British soldiers who had died in the service of company and country during the course of the various campaigns in the region. Unlike Moorhouse’s tomb in Madras – which was highly specific and individuated with its sculptures depicting not just Moorhouse himself but allegorical figures of Britannia and the East India Company – the stark neoclassical structure of the unmarked tombs in Home’s engraving evokes timelessness and universality, and a significance which transcends the commemoration of individual officers or concerns. The motif of the tomb in the landscape had an art-historical pedigree of which Home would have been acutely aware, one which had emerged within the French landscape tradition in the seventeenth century, but had more recently been revived by Richard Wilson, a painter who played a crucial role in the foundation of a landscape tradition in Britain.21 Home’s viewers would have been extremely familiar with this kind of historical landscape, and may well have associated the engraving with earlier landscape painters’ attempts to elevate their genre with references to classical history, and with the concerns of moral philosophy.22 However, the engraving is not only concerned with elevating landscape through the appropriation of history, but also attempts to inscribe history and death onto the landscape itself, and in doing so to elevate recent British colonial history to the significance of the classical past. This is a notable tendency of publications such as Home’s, which invariably interweave narratives of recent British military history within the established strands of Hindu and Muslim history that are already visible within the landscape – pagodas, shrines, mosques and mausoleums. These publications (like Turner’s later watercolour The Siege of Seringapatam) construct and visualise three cultures within the landscape of Mysore – an ancient Hindu culture; the more recent ascendancy of the Muslims through Hyder Ali (whose family tomb at Colar, and individual tomb at Seringapatam were frequently depicted by British draughtsmen, including Home, Allan and Hunter); and the new chapter which was now in the process of being written onto the landscape, the colonial achievement of the British. While history and memory may be distinct processes, they are nonetheless generated concurrently within the pictorial narrative of Home’s publication.

Fig.5

Robert Home

Burial Ground at Bangalore engraved by James Fittler 1792

Etching on paper

Copyright © The British Library Board

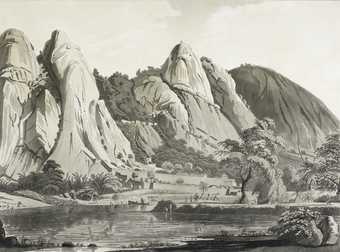

James Hunter’s views, meanwhile, also incorporate death into the landscape, but include a number of tomb scenes that bear little ostensible relationship to the military campaigns which structured Home’s work. Among these is an image of rural Indian figures, soldiers and peons around a large tomb (fig.6). The elegiac mode of this composition, with its contemplative figures, calls to mind Nicolas Poussin’s Et in Arcadia Ego (Musée du Louvre, Paris), a painting which in the eighteenth century was understood to denote that death was to be encountered even in Arcadia.23 This idea may perhaps have had some resonance with military men such as Hunter who would have been acutely aware that the pleasures of a life of relative freedom in the east were counterbalanced by the constant awareness of mortality that war and illness carried with them.24 The focus on tombs and mortality – and the contemplative responses that are structured in relation to them – throughout the four publications acclimatises the viewer to recognise death elsewhere in the landscape, particularly when the images are looked at in conjunction with their accompanying text. In their respective publications, both Home and Colebrooke draw attention to the plight of British officers and soldiers who had been taken prisoner by Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan during the second Anglo-Mysore War. A number of personal narratives, journals and letters attest to the torment of the prisoners’ incarceration in horrific conditions, where they were subjected to scorching heat or night-time cold, poor sanitation, acute hunger and thirst, and humiliating treatment – at times kept in irons, and some of them forcibly circumcised. In addition to their incarceration in prisons at Bangalore and Seringapatam, many of the captured soldiers and officers were imprisoned at hill forts, or ‘droogs’, in the surrounding countryside, locations which account for an overwhelming proportion of the imagery in Colebrooke’s, Allan’s and Home’s publications. In the text accompanying an image of Sewandroog, or the ‘rock of death’ (fig.7), Colebrooke recalls the fate of twenty officers and thirty soldiers taken prisoner during the second Anglo-Mysore War who were moved to the fort at the top of the hill, where they were fed meagre rations and kept in a continual state of suspense regarding Tipu’s intentions. Meanwhile, the text accompanying Colebrooke’s image of another hill fort, Ootradroog, produces two narratives, one detailing the successful capture of the fort during Cornwallis’s campaign in the third Anglo-Mysore War, the other recounting the fate of Randal Cadman, a midshipman of the Hannibal, and his fellow prisoners who endured ten years of captivity on the droog, their existence made even more miserable after they tried to escape down the steep precipice and were recaptured in woods nearby. The images of the droogs, therefore, offer the viewer the opportunity to oscillate between narratives of conquest and loss as he or she confronts the vast, sheer faces of the numerous hill forts.25 Highly individuated in both their forms and narratives, these precipitous locations represent more than mere backdrops. Their inescapable and apparently unscalable crags, set within compositions which lack any kind of visual recession, force the viewer to confront the physical reality of military experience in the colonial environment, and to choose between accessing narratives of death, suffering or conquest. In this regard, publications such as Home’s and Colebrooke’s coincided with the burgeoning market for military memoirs, which became increasingly concerned with the affective and personal experience of war during the 1790s, a period when conflict was raging in Europe as well as in the far corners of the empire.26

Fig.6

Henri Merke after James Hunter

View on the Road at Struppermador 1804

Aquatint

Copyright © The British Library Board

Fig.7

J.W. Edy after Robert Hyde Colebrooke

South View of Sewandroog 1794

Aquatint on paper

Copyright © The British Library Board

Hyder and Tipu’s policy of moving their prisoners around the Carnatic is evidenced in the narratives and journals of those individuals who survived to tell the tale, as are the torments endured by British officers and soldiers, compounded by their being forced to march for days in the extreme heat – starving, bound and often ill, injured or dying – between the hill forts. For example, the story of James Bristow, a soldier in the Bengal Artillery, is typical in recounting the various locations of his incarceration, moving between Seringapatam and the various droogs which are represented in the published sets of views by Home, Colebrooke and others. Indeed, the fact that he and his fellow soldiers moved around the countryside is crucial to Bristow’s account of his captivity. In the preface to the first edition of his narrative, published in Calcutta, Bristow justifies adding to the already significant stock of information on the British prisoners of war, and distinguishes his tale from that of more senior members of the military:

A captivity of ten years during which period several removals from one place of imprisonment to another took place, and many changes in point of treatment occurred, includes much more variety than the account of what befell our officers, who remained under close confinement, till delivered up; and admitted more opportunities to see the country, to converse with the natives, whose language naturally became familiar … and to learn the fate and disposal of a number of fellow captives, not liberated at the peace, some of whom had been prisoners for many years … in short, to be better informed than Gentlemen who were never suffered to step beyond the limits of their prison wall. Several of the vexations and acts of violence committed against the private soldiers could not reach the knowledge of the officers, though many of them came to their ears; nor could they know what befell them subsequent to their release.27

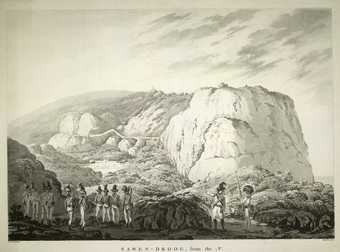

Bristow not only denotes a hierarchy of suffering – distinguishing those soldiers who were forcibly marched through the Carnatic from the more senior officers who apparently suffered fewer ‘vexations’ in their fixed prison sites – but also indicates that being moved around the inhospitable landscape was a defining aspect of his captivity.28 Encountering and enduring the landscape, whether as prisoner or victor, is a formative aspect of war. Bristow’s experience mirrors, in a debased and nightmarish mode, the kinds of tours that came later and which attempted to reconstruct or, at least access, the physical encounters which had gone before them: Henrietta Clive’s for example, which took place shortly after the death of Tipu and sought out the key locations of the Anglo-Mysore and Carnatic wars, or those printed views published by artists and officers such as Home, Colebrooke and Allan, whose sequences of images provided a kind of armchair tour focused upon the various hill forts associated with recent episodes of conquest and captivity. Within these publications of views, parallel strands of history structure the imagery, which is readily associated with, and maintains, two separate narratives of colonial engagement – the physical and mental trials of the British prisoners who forcibly ‘toured’ the Carnatic hill forts, and the triumph of Cornwallis’s campaign in the third Anglo-Mysore War, which was dependent upon the capture of those same locations. Even the engravings without textual explanation indicate the manner in which they might be approached. One of Allan’s views of Sewandroog (fig.8), for example, includes a group of military figures in the foreground who contemplate its vast precipice, recalling perhaps the recent campaign or the fates of their comrades who had died during their incarceration in the fort. Although it was common for topographical artists to insert figures into the viewer’s space, often representing themselves in the process, it is clear that, in Allan’s imagery, the soldiers’ physical and mental experiences are intended to provide the framework for viewing the landscape. Once again, the landscape can be read as a kind of memorial to those who have died in the course of the British campaigns in this region, not least because of the grizzly ends which many of the prisoners met. Poisoned by Tipu’s men or having died from disease, their bodies were typically thrown over the precipice of the hill, where they would have been devoured by tigers or vultures.29 That the landscape itself acts as a location for, and a commemoration of, death is illustrated once again in Charlotte Clive’s journal when she observes the simple memorials in the landscape to those who have been carried off by tigers: she records passing many piles of stones where a man had been killed, each passer-by silently adding a tribute of a single stone to the heap.30

Fig.8

Alexander Allan

Sawen-Droog engraved by John Wells 1794

Aquatint on paper

Copyright © The British Library Board

The visual ‘tours’ of the Kingdom of Mysore offered by Home and his military counterparts were, therefore, structured around episodes and experiences of the wars which preceded their publication, alternating between different forms of recollection and encounter. On the one hand, the narrative of British military success and of a cumulative campaign that progressed from one hill fort to another is clearly delineated within the sequence of engravings. However, the images also provided moments of aesthetic encounter with the landscape that sought to align the experience and aftermath of war with modes of viewing that were culturally elite and positioned within the framework of an elevated tradition of landscape painting.

The extent to which aesthetic and military concerns were brought together in viewing the landscape of the Carnatic may be gleaned from textual accounts of touring this region. In the description accompanying his view of Sankry‑Droog, artist Thomas Daniell describes the peculiar impression that this hill fort made upon him:

From this elevated point the eye commands an extensive view of the vale and distant mountains. The scene is grand; but of that dreary aspect, which being neither softened by the beautiful, or elevated by the magnificent, produces in the mind a mixture of horror and melancholy … The fortress in which the spectator is placed seems elevated almost into the clouds; its sides in many parts are formed of perpendicular cliffs; it is moreover surrounded with every impediment, natural or artificial, than can render access either impossible or difficult; and all this to enable one little tyrant to resist the hostility of another, or to favour his own projects of vengeance or plunder.31

As an artist encountering the war zone by following the path taken by Cornwallis’s army, it is not surprising that Daniell should alternate between a moral distaste for the conflicts which have scarred the landscape, and a mode of viewing which seeks to evaluate scenery according to its extent and aesthetics. Daniell prompts the viewer of his image to encounter the inhospitable landscape as a facet of the hostility of its tyrannical rulers, but in deploying the terminology of the sublime, with its prioritisation of terror, gloom and immensity, it is clear that a particular aesthetic experience, and even pleasure, might be derived from one’s perusal of the image as an armchair traveller.32 Nor were such aesthetic reflections and associations the exclusive concern of professional artists. The journals of numerous travellers in this region attest to oscillating modes of landscape viewing that moved between the conventions of aesthetic evaluation and more functional concerns. Captain William Lambton’s journal of his tour through the Carnatic in 1799, for example, assembles a range of detailed observations on the landscape that encompass pragmatic descriptions of forts alongside passages which are calculated to display his elite sensibilities for a more literary or aesthetic landscape. Sometimes the two merge together, as they do in his account of Chittledroog, which fuses the languages of logistics and aesthetics to produce something which might be described as a military sublime:

The area contained within the line is such a confused mass of works, rocks, tanks and palaces, as is not within the power of description … Whatever part of these mazes of fortifications the confounded traveller may perceive himself to be in, he will look up in astonishment at the number of batteries that can direct their fire immediately upon him … The number of antient walls and trees which intervene while the spectator directs his eye to the stupendous piles of batteries that appear among the clouds, he is bewildered in the diversity of objects, which, tho’ destitute of order and arrangement, are yet tremendous and awful.33

The slippage between Lambton’s military and aesthetic concerns in this passage is suggestive of the fact that the various facets of an officer’s elite identity were not maintained as distinct attributes but were continually coalescing. To be an officer one had to be, after all, a gentleman – the two went hand-in-hand, and it is therefore not surprising that someone like Lambton should seek to demonstrate his aesthetic sensibilities (which were, of course, a facet of his elite social identity) alongside his attentiveness to his professional duties. This tendency may be seen also in publications such as Home’s where a representation of the hill of Ramgherry is presented in terms of a kind of military picturesque, with fortifications and canon incorporated into an appropriately wild landscape composition. This view is immediately succeeded within the publication by an extensive view of Shevagunga (Shivaganga) which is demonstrably Claudean in its composition, featuring a repoussoir tree, a road that meanders from the foreground to the distant horizon, and a pair of classicised natives. That a viewer could move between aesthetic modes by turning a page, or could alternate between artistic and military concerns within a single image is suggestive not so much of the demand of a broad market (though there is certainly an element of this) as of the actual practices of military men like Lambton. While going about his military business, he not only spotted the sublime potential of the war zone, but was quick to identify Mysore with ‘antient Arcadia’ and equate the colonial landscape with ‘the English park upon a large scale’.34

Beyond the execution of imagery such as that examined here, military tours and draughtsmanship engaged with the landscape of south India in ways which were more multifarious still: cartography, surveying, and agricultural and botanical tours, for example, produced a plethora of imagery and information which suggests further ways in which the military draughtsman could move between different modes of knowledge, experience and viewing.35 The military draughtsman brought multiple facets of his social identity and professional experience to bear on his landscape imagery. The pictorial sources with which Turner engaged when he ‘worked up’ the sketches that he acquired from officers such as Sydenham were complex, drawing upon memories of war that were encountered and evoked not merely within individuals but through landscapes, and were additionally shaped through gentlemanly aesthetic knowledge, tastes and accomplishments. In adapting the topographies and viewpoints of the locations he represented, Turner demonstrated a familiarity with the aesthetic, professional and individual processes which determined the wider production of landscape drawing in the aftermath of the Anglo-Mysore Wars.