Remember – we live next door to the ocean, but we also live on the edge of the desert. Los Angeles is a desert community. Beneath this building, beneath every street, there’s a desert. Without water the dust will rise up and cover us as though we’d never existed!

(pausing, letting the implication set in).1

The difficult and endlessly circular relationship between a basic need for water and the reality of California’s desert landscapes and prolonged periods of drought forms the backdrop to one of the most accomplished Hollywood feature films of the 1970s: Chinatown (1974), directed by Roman Polanski with screenplay by Robert Towne. The above admonishment from former mayor of Los Angeles Sam Bagby to the City Chambers, during a key expository scene regarding the proposed Alto Vallejo Dam and Reservoir, succinctly articulates the perilous environmental state and its resultant effect upon the collective Los Angelino psyche of what one could characterise as a heightened state of tension. This tension underwrites mundane everyday existence, while simultaneously provoking an epic struggle for the barest of essentials. The neo-noir film, which shoots Los Angeles and its outlying areas in a palette of sun-bleached, chalky hues rather than the conventional spectacle of noir chiaroscuro, underscores the corruption and political perversions conditioning the struggles over water in the city in the 1920s and 1930s, and emphasises the long historical gestation of this particular plight. The continuous sense of pressure that results from this fluctuation between liquidity and dryness, full reservoirs and empty dust bowls, seems eerily analogous, I want to suggest, to the medium of drawing and its own fundamentally split possibilities: dry, dusty graphite versus fluid pen and ink. The precise and arid graphite drawings of the Latvian-born American artist Vija Celmins (born 1938) are in many ways evocative of the physicality of the Californian landscape.2

In Chinatown, drought is made mythic: assuming the position of a dramatic threat in the narrative, propelling events forward and instilling in the characters a heightened awareness of their shifting surroundings.

Celmins lived and worked in Venice Beach, California in the 1960s and 1970s after moving from Indianapolis to undertake an MFA at University of California, Los Angeles. The artist has said:

I’m an Eastern European, so didn’t see the desert until I moved to California in 1962. I would drive out into the desert. I liked it. It was a place that made you feel as if your body had no weight. At first I thought that there was nothing there. Then I began to see things. I was always having to adjust my eyes back and forth – both far and close, which is how I think about my own work sometimes. It lies somewhere between distance and intimacy. That early discovery about that different kind of space – where you don’t know really how far or near something is – had a subtle influence on my work, especially that of the late 1960s and 1970s.3

Celmins’s expression of her complex relationship to the desert tempers geographic specificity with an emphasis on the more abstract spatial and visual changes this new landscape brought about within her practice. Indeed, the various subject matters of Celmins’s drawings of the 1960s and 1970s are not geographically bound to California; rather they are based upon photographic images of oceans, deserts, lunar surfaces, cloud-filled skies and galaxies. And yet all of these spatial typologies (and they are definitely typologies rather than specific places) have in common that vague impression of lying ‘between distance and intimacy’ to which the artist refers. Infinities becomes intimately scrutinised, and Celmins rewards the viewer with a carefully wrought visual tension to match that of the cinematic desert.

Vija Celmins

Untitled (Desert-Galaxy)

(1974)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

This article will focus on one work on paper by Vija Celmins: Untitled (Desert–Galaxy) 1974 (fig.1). This drawing presents two wholly separate images, bringing together the dusty landscape of the extreme west with another extremity, that of outer space. This work belongs to a group of seven (all graphite on acrylic ground on paper works) that were first exhibited, alongside six other untitled sea and constellation drawings, at Felicity Samuel Gallery in London in 1975.4 By using Untitled (Desert–Galaxy) as a lens through which to re-examine current theoretical interpretations of drawing in the late 1960s and 1970s, I hope to articulate the extent to which Celmins presents a different space for drawing, detached from the legacies of the dematerialised and expanded drawing fields of 1960s New York.5 In 1967 the artist stopped painting, shifting her attention to the development of a sustained body of graphite on paper works.6

Fig.2

Vija Celmins

Heater 1964

Oil on canvas

1205 × 1219 mm

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchased with funds from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee 95.19

© Vija Celmins

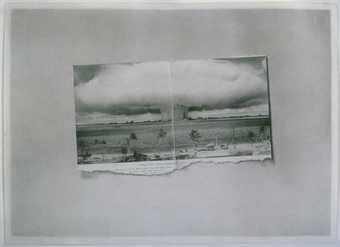

Celmins had spent her post-college years in the early 1960s training her eye upon mass-produced and functional objects, making paintings that were seen as important, if peripheral, contributions to the vibrancy of the Pop-inflected West Coast scene.7 Meticulous yet menacing oil paintings of her studio’s household objects, for example Heater 1964 (fig.2), coolly rendered in chalky grey tones with occasional flashes of bright warning colour, are rooted in the careful rendering of fragments from the everyday, in an apparent acquiescence to the mass move towards Pop. However, the singular care and attention to the individuality and materiality of her personal items, apparently detached and isolated from the streams of mass manufacturing, marks Celmins’s course as somewhat different from her Pop contemporaries in Los Angeles and beyond.8 Indeed, the artist would swiftly move from this kind of object depiction to drawings such as Bikini 1968 (fig.3), with subject matters based not on three-dimensional objects observed from life but instead paper ephemera, newspaper clippings and found photographs. This rapid transition suggests the artist’s burgeoning interest in the mediated world of photographic and indexical traces of objects, histories and locations, rather than physical, solid things. Bikini depicts in persuasive trompe l’oeil fashion a captioned photograph torn from a magazine, its paper scored deeply down the centre of the image. The photograph shows an atomic blast which took place in Bikini Lagoon on 25 July 1946, part of the United States’ Operation Crossroads – a series of twenty-three nuclear detonations within the Micronesian atoll. The ripped fragment, centrally positioned, sits in front of a smudged grey ground, casting a small edge of shadow. While its nuclear testing subject matter is relevant to a prominent strand of wartime imagery in Celmins’s 1960s work, I am more interested here in the process of recycling by which such images are reconfigured through drawing as trompe l’oeil avatars of their former ‘clipped’ selves.

Fig.3

Vija Celmins

Bikini 1968

Graphite on acrylic ground on paper

340 x 464 mm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Edward R. Broida

© Vija Celmins

Celmins’s development from this paper ephemera series of 1968 to work of six years later such as Untitled (Desert-Galaxy) would further consolidate this rejection of direct observation in favour of the intermediary photographic surface, configured as information to be scanned.9

Rather than attempt to situate this one drawing’s place within the artist’s wider output of painting, drawing, printmaking and a few highly significant sculptural objects, this article will take an almost microscopically close view of this one work among many.10

In a sense, such an approach seems well suited to the artist’s practice. In its close-looking, distillation of images and concentrated formal qualities, Celmins’s drawing invites careful speculation and rather cautious theorisation. One could argue that a central drive of her work is to brush aside definitive interpretations, so as to encourage open-ended flexibility and perhaps even doubt regarding the issue or position of its meaning. It is therefore important to acknowledge the inevitably fragmented and partial nature of the set of observations made here, and to cultivate this liminal site of uncertain signification as something productive, rather than frustratingly elusive.

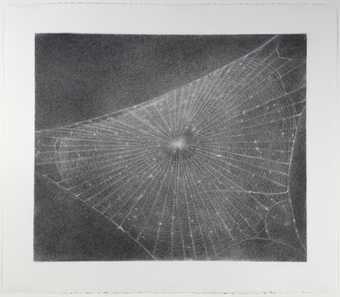

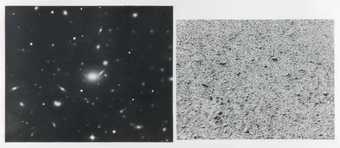

Untitled (Desert–Galaxy) is comprised of two side-by-side images, derived from photographs of frontier sites: iconically vast places, defined by distance. The uneven, slightly irregular positioning of the two drawings in relation to the paper support is immediately noticeable. They do not match up on either axis, with the desert image hovering just above the bottom edge of the galaxy. The difference in the size of the two drawings is clear, the galaxy image on the left-hand side being taller, almost spanning the vertical axis of the paper. This difference is slight, but it ensures the images retain the status of object representations, as opposed to variable fields that can expand or contract to fill a page. The photographs are, however, enlarged in the process of drawing: Celmins notes in her 1992 interview with Chuck Close that they are tiny, dog-eared things.11

This drawing of two individual images appears almost widescreen in the elongated landscape proportions of its paper support, setting up a double vision effect where the viewer is unable to take in both images at once, but rather must move between them in a rhythmic back and forth. It is a surprisingly long piece of paper, with the two rectangular drawings together nearly filling its widescreen façade, and yet the images remain quite separate, inhabiting the same support but retaining their distinction. It is a dual vision predicated on monocular means – the camera. Two images is not quite enough to have, or even initiate, a series, although in their negative/positive relation to each other (heaven and earth, black and white), the images do engage in a kind of seriality, as well as referring to the negative/positive process of photography.

While the galaxy image, specifically of the Coma Berenices constellation, is a general reference source found by the artist in the bookshop of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Susan Larsen confirms that the 1973–5 desert source photography is the artist’s own work, taken on numerous trips to the Mojave Desert near Death Valley, north-east of Los Angeles.12

These neighbouring images therefore have vastly different photographic sources: one published, the other a personal snapshot. Yet this difference, along with the vast difference in scale between the photographs’ subject matters, is almost completely effaced when brought together in the drawing, as the representations adjust to positions of equivalency.

Regarding the actual drawing technique, the graphite surface of the galaxy image is worked to a high density. Built up, the graphite appears smooth with a slight shine to it, which is especially reflective at close range. The surface appears so smooth because of the prior preparation of the paper with an acrylic ground, which provides an intermediary layer of paint between the paper and the pencil. The artist has explained the origins of this particular technique, commenting: ‘When I first started doing them, like Cassiopeia and the Coma Berenices drawings, I found when I drew with just the pencil I had to press real hard and dig in to be able to break the surface of the paper. So I bought a sprayer and sprayed backgrounds of a kind of gesso. It seals the paper so the graphite sits on top of it. It’s like a veil.’13

This veiling, without direct intervention from the artist’s hand, transforms the porous and supple paper support into an eggshell-like veneer of flattened space.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the doubts and ambiguities that underwrite Celmins’s engagement with her subject matter, it is worth thinking carefully about the compositional make-up of the places she selects to re-render in pencil. The desert is by definition a landscape that has practically no rainfall, and as a consequence its terrain is constantly shifting – the wind turning over and redistributing the fine particles of the topsoil, revealing the pebbles and boulders beneath. The astronomical system of a galaxy is composed of stars, stellar remnants, gas, dark matter and dust. Scientifically speaking, the individual particles of cosmological dust range from a few molecules to only 0.1mm in size, but account for a significant proportion of a galaxy’s mass. I mention these dry facts to suggest that, despite the obvious difference in scale between a small section of the desert floor and the area captured by a long-range telescopic photograph of the Coma Berenices constellation, these sites are united in their compositional make-up of tiny particles, which are accumulated in much the same way as Celmins accumulates her pencil marks.

Fig.4

Vija Celmins

Irregular Desert 1973

Graphite on acrylic ground on paper

305 x 381 mm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Edward R. Broida

© Vija Celmins

The pinpricks of light scattered across the galaxy image, of various sizes, shapes and clusters, form a photographic record of astronomy in translation. Accomplished by barely touching the paper, they leave the pale gesso-coated surface to radiate against the dark, dense graphite of deep space. Celmins’s graphite feathers its way towards these empty centres, a sort of insistent stroking of surface that seems to lend the stars a real presence and weight within the drawing, despite their status as areas of negative space. As a result of this technique of gradual and graduated graphite densities, the galaxy image feels more dusty and hazy than its accompanying desert image, where the neat rock formations are individually delineated in a pattern-making fashion, the almost mosaic-like arrangement of boulders contoured on top of the light grey background. Some of the larger rocks cast shadows, so although the plane is flattened out, there is a kind of recessive perspectival orientation still in play, in contrast to the visual flatness of the galaxy image which paradoxically represents far greater physical space. The desert particles are so precisely positioned as to seem artificial – like cleaned up props, or composed irregularities. They have been carefully plotted in translation from photographic source, and take on an air of unreality and utter stillness. Contemporary British artist David Musgrave has written of a related work, Irregular Desert 1973 (fig.4), that ‘the subject of the work, by way of a loose metonymy, refers back to its material nature’, i.e. the dusty graphite means.14

This drawing, also exhibited at Felicity Samuel Gallery in 1975, is useful to highlight this economy of technique and subject that Celmins keeps in play across these various investigations of the desert floor, but also to introduce another facet of her practice. Irregular Desert is a single image work. Contemplating its small rectangle of desert floor alongside the right-hand section of Untitled (Desert–Galaxy), it is hard to establish whether or not the same photograph has been used to draw both works. The closer I look, the more my gaze keeps slipping, unable to register or confirm exact parallels between the images, losing my place between the stones, small and large. Doubt creeps in. I decide that they are extremely similar, but not quite identical, sections of the desert, from photographs perhaps only a few frames apart on the roll of film. The compositional differences are miniscule, but they are reinforced by the shifts in tone and texture, the different pencils used. The smudgy Irregular Desert appears to have been drawn using soft B number pencils, whereas the desert of Untitled (Desert–Galaxy) is much crisper, almost certainly executed with hard H pencil lines. This spectrum of reiterative imagery is thus given the bracing support of another spectrum: that of graphite gradation.

Celmins’s works on paper from the late 1960s and early 1970s demonstrate a conceptual approach and a technical drawing procedure that are drastically different from the vast majority of drawing from this period. This alterity is in large part due to her drawing’s photographic base. By the late 1960s, a new unfolding of drawing in the expanded field (to modify Rosalind Krauss’s essay title of 1979, ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’, as recently suggested by Anna Lovatt and Ed Krčma) was well underway in various manifestations, such as the first wall drawings of Sol LeWitt that were executed in 1968.15

The quiet tone and modest scale of Celmins’s work appears very different to these newly enlarged ambitions of spatial presence and quasi-sculptural configuration. That the intervention of sculpture was responsible for loosening the conventions of drawing and unravelling it spatially can be seen in the work of Eva Hesse, Fred Sandback and Robert Morris, amongst others. This work was very much based upon extrapolated and transformed linearity. In the case of Celmins, however, it seems clear that photography was the catalyst that generated an antithetical but equally responsive shift in the medium, one that was focused on a refusal of both linearity and any kind of engagement with architectural or phenomenological space.16

To this end, Celmins’s drawing practice of this era speaks less to the process-motivated actions that pervaded the late 1960s and more to the technicalities of a revived super realism in painting, which found particularly strong roots on the west coast in the early to mid 1970s. Realism is a term that sits uneasily with Celmins’s work, so many times has her subject matter been removed from any sort of reality and distorted through lenses and reproductions. Nevertheless, hers is fundamentally an image-based, photographically-assisted practice, sharing some affinities with contemporaneous realist painters Chuck Close, Richard Estes and Janet Fish. It seems important to acknowledge the strange and hard to categorise nature of what Celmins was undertaking in her work at this time. Her practice had evolved beyond the basic conceit of copying a photograph, while leaving behind any desire to interfere too obviously with the images themselves (see the earlier Ocean with Cross 1970). The conceptual pulse of the work, however, remained coolly opaque.17

The February 1974 issue of Arts Magazine was dedicated to a scholarly exploration of super realism, with a collection of essays that examined the return to a strangely Pop representational mode, in the guise of slick surfaces and glossy representations of consumer goods, spaces and commercial buildings – Richard Estes’s Escalator 1970 being the iconic painting of the loosely coalesced movement. As H. D. Raymond wrote in this issue of these so-called ‘Newer Realists’, their works ‘offer a universe of phenomenon from which all traces of the numinous has been drained. Only matter is represented and only the surface characteristics of brittle matter.’18

While Celmins is a world away from the subject matters and painterly techniques of super realism, it is nonetheless an intriguing point of comparison. Raymond’s talk of brittle matter and a draining of affect seems essentially close to what I understand to be a quality of Celmins’s own work at this time, which, in dispensing with painterly slickness for the equally unforgiving multiple coatings of slightly shiny graphite, transforms her imagery into a delicate yet impermeable and inflexible shell – mediated nature as self-contained as the blank reflexivity of super realism’s totemic commercial structures.

Jonas Storsve, curator of Celmins’s 2006 Centre Pompidou drawings retrospective, analysed the construction of her desert drawings (based on photographs taken on the artist’s various walks in California, Nevada and New Mexico) and considered their relationship to an important later work:

Celmins managed to eke a multitude of grey tones out of the graphite to yield vibrant drawings. On these walks, she developed an interest in stones, which she collects to this day and which she used years later as the subject of To Fix the Image in Memory 1977–82 (fig.5), a sculptural piece composed of eleven found stones and painted bronze replicas of them.19

Fig.5

Vija Celmins

To Fix the Image in Memory 1977–82

Stones and painted bronze, eleven pairs

Dimensions variable

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Edward R. Broida in honor of David and Renee McKee

© Vija Celmins

This notion of the replica is crucial – art historian Richard Shiff has described this rare three-dimensional piece as ‘a work of trompe l’oeil sculptural imitation’.20

The connection between this multi-part painted sculpture, which took five years to complete (a period signalling a halt in Celmins’s drawing practice, and her subsequent return to painting in the early 1980s), and the earlier drawings such as Untitled (Desert–Galaxy) is worth remarking upon. As Shiff notes of To Fix the Image in Memory: ‘Holding model and representation in suspended juxtaposition, Celmins’s display renders priorities undecidable.’21

This uncertain relationship between physical model (or photographic source imagery) and translated representation, whether sculpture or drawing, confers an oddly distended temporality upon the work, which seems to avoid a straightforward logic of production.

Only two of the drawings at Celmins’s 1975 Felicity Samuel exhibition were dual-image works: Untitled (Desert–Galaxy), originally titled as Untitled Constellation and Desert, and Double Galaxy (Coma Berenices) 1974, originally titled as Untitled Constellation (double), shown alongside several individual deserts and constellations, of varying image size. In her catalogue essay for Celmins’ touring retrospective of 1992, Judith Tannenbaum explained the genesis of the dual-image format: ‘As a result of working for long periods of time with a small source photograph next to her graphite drawing, Celmins did several drawings in 1974 in which two images were juxtaposed on the same sheet: a small and large version of the identical section of the desert floor; a small and large version of the Coma Berenices; and the galaxy paired with the desert – the heavens with the earth.’22

This final pairing, Untitled (Desert–Galaxy), must therefore be viewed in light of these other works that proliferate copies small and large, regular and irregular – each time the image is worked over, another precisely rendered copy, seemingly identical but perhaps not, is brought into being. This erosion of uniqueness refers back, inextricably, to the inherently duplicative nature of the photographic source. 23

When considered as part of this wider group of galaxies and deserts, the skill of Celmins’s drawing would seem to shift from the difficulty in rendering individual images to the uncanny ability to achieve the same precise image at every iteration, across multiple works, varying only the pencils used, the pressure of the graphite on the paper surface, and the resulting tonal densities. Celmins has said of her practice: ‘The image is just a structure I don’t have to think about, like Jasper Johns’s flag.’24 We might find that forgetting is as important a mechanism as remembering. If the absurd level of detail registered via the photographic structure permits the artist (and the drawing itself) to forget, then a disruption of the standard creative ‘inventiveness’ of drawing is at stake. The desert and galaxy, two complex patterns of visual information, are not brought forth from the recesses of the artist’s consciousness or worked out from a direct life encounter; they simply filter through from photograph to graphite form, broken down into small particles as they are deposited on the paper. While this seems to be a rigidly anti-subjective approach that shifts the decision-making processes from the artist’s hand to a predetermined formula, I would contend that this is an act of letting go (within carefully controlled parameters) that confers an almost perilous sensation of freedom upon the activity of drawing, destabilising the artist’s relationship to her work, which appears both distant and frighteningly intimate – to echo her description of desert space quoted earlier. Celmins, speaking more recently about Untitled (Desert–Galaxy), has insisted:

It’s like a double vision pushed into one. It really has no meaning. These images just float through from my life; they have no symbolic meaning … it has flatness and image … but the image is like a ghost of something remembered.25

Celmins’s reference to a double vision made singular confirms that this drawing cannot be read as a traditional diptych, but rather as a single field holding two separate pieces of visual information in close proximity and tension. The claim of a lack of definitive meaning in the chosen images is a consistent policy with the artist, as alluded to previously. Emphasising the physicality of the photographic object rather than its illusionistic or symbolic content is a way of short-circuiting the many cultural and personal associations these photographs in and of themselves could potentially evoke; the language used here really does suggest Celmins’s position to be one of detached intimacy. If the image is a ghostly memory trace, it becomes a lingering, empty shell that can endure many layers of superimposition. In her work there are layers that create distance, just as the photograph is a record of spatial and temporal distance from its subject. As Celmins asserts: ‘The photograph always seemed to me kind of dead … I crawl over the photograph like an ant. And I document my crawling on another surface.’26 This again reveals the duality of detachment and proximity that informs the artist’s relationship to her subject matter. Emptied of life, drained of energy – the photograph’s stillness becomes a carapace over which the graphite skims, doubling the patterned shell of the desert or galaxy.27 Just as dust is the common or household name for the inert, dead matter that clutters our spaces, so too is the photograph the dead matter onto which Celmins’s drawing practice clings. As David Musgrave reminds us, ‘the majority of artworks are, fundamentally, arrangements of lifeless matter … Drawing produces its own fossil.’28

The Italian artist Giorgio Morandi (1890–1964) is cited throughout the Celmins literature as a major influence on the artist, particularly with regards to her studio paintings from 1964–5 such as Heater (fig.2), which seem to channel his use of everyday objects and his sensibility of a muted grey palette together with a chalky, almost desiccated, handling of oil paint.29

To me, Morandi represents a sealed, insular and strangely timeless space. He was making work up to his death in 1964, which means that his later paintings are contemporaneous with early Pop, an odd yet somehow fitting chronology. This is a still-life world where objects huddle together, arrangements shift incrementally between pictures, and forms are subjected to close, almost paralysing, scrutiny. Morandi painted from life, endlessly repositioning his selections from a motley collection of bottles, boxes, vases, cups and other household receptacles on the studio table, marking out various compositions by drawing around their bases.30

Like Celmins, he seems far less concerned with linear incident and detailing than the meeting of surfaces and their careful tonal gradations. Indeed, he was known to remove all labels from the objects, chiefly bottles but also vases and old tins, often covering them in white or light coloured paint to achieve seamless regularity. In many of his late still lifes the assembled objects lose any sense of individual distinctiveness to coalesce into one densely worked surface, depthless and free of delineation and yet humming with the collective pressure of things packed tightly together. Morandi’s incremental transitions produce an almost performative sense of contemplative reiteration, working up a subject over and over until its relevance is rubbed away and smoothed out, much as the endless space of the Coma Berenices is slowly rubbed into and eventually contained by a smooth rectangular paper space. It hardly needs to be said that there is a significant generational difference and a huge conceptual gap between these two artists. Yet I would argue that what is shared between Celmins and Morandi helps pinpoint what is so distinctive (in the artistic climate of 1970s America) about the younger artist’s approach to drawing: her effacement of line and desire not for shorthand notations or sketch-like efficiency, but prolonged and intensive study.

In her introduction to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2002 retrospective of Vija Celmins’s prints (a career-long devotion to printmaking being another characteristic shared by Celmins and Morandi), Samantha Rippner suggests that: ‘Like Morandi, Celmins succeeds, through a mastery of mark and process, in creating not only a richly patterned surface but also a still, hermetic space that fixes our gaze.’31

This ‘hermetic space’, sealed within the picture plane, recalls the equally hermetic studio – the cloistered site of daily, private activity from which these small worlds spring, as contained and controlled as their immediate surroundings. Morandi could be considered the ultimate studio artist: he rarely travelled and his studio was a room in the house he shared with his sisters, creating a closed circuit of life and work space. I am less interested in the biographical aspect of this than what it means to think about small-scale, closely handled works (on paper or on canvas) as products of the studio, as products of intense fashioning and contemplation.32

As curator Matthew Gale has observed: ‘Beside the pursuit of the harmonious there is also an anxiety in Morandi’s work. The surfaces and the interactions of objects in the studio are felt, hesitantly.’33

I would say that this anxious hesitancy locks into Richard Shiff’s notion of the ‘undecidable’ priorities in Celmins’s art – as figured in its oscillation between the object and its representation. What is known to be true, as visual fact, is continually questioned and undermined. In this slippage, the space of the studio becomes a space of indeterminacy, confusing the gap between illusion and reality. In a 1967 article in Artforum on Morandi, critic Sidney Tillim relays a description by John Rewald of the artist’s Bologna studio, visited shortly after his death in 1964:

On the surfaces of the shelves or tables, as well as on the flat tops of boxes, cans or similar receptacles, there was a thick layer of dust. It was a dense, gray, velvety dust, like a soft coat of felt, its color and texture seemingly providing the unifying element for these tall boxes and deep bowls, old pitchers and coffee pots, quaint vases and tin boxes.34

This evocative account returns me to one of the recurring motifs of this article: dust and its relationship to drawing. Rewald’s description summons a scene of both delicate stillness and haptic intensity. As a particle-based substance like graphite powder, dust can settle or be sprinkled across a surface – it is a passive agent, unlike the active thrust of linear drawing. And yet, rather than connoting neglect or simply the interminable passage of time, the dust in Morandi’s studio signifies his very method, style and soft precision. The drawings of Celmins are equally steeped in dust – as the material foundation, dust provides the base note for their unreal and incomplete illusion. This dusty quality is especially visible in her later drawings, begun in the mid 1990s, that use charcoal as opposed to graphite.35

As cultural historian Steven Conner puts it: ‘[Dust] is a powerful quasi-object, a magic substance, something to conjure with … Dust is amorphous, without form and almost void. But this very fact allows it to be thought of as metamorphic’.36

Magic, a term embedded in the wider context of illusionism, and often associated with historical receptions of the trompe l’oeil technique, is here paired with the utterly mundane matter of dust: a thing, like drawing, which seems to achieve only partial objecthood. Conner’s central assertion certainly seems apt: it is dust’s hovering formlessness that imbues it with powers of transformation – look at the coherence it achieves for Morandi’s miscellaneous collection of everyday objects. That it lacks something, that it is structured by a void, is what makes it such a crucial signifier for this strand of drawing practice, where infinitesimally small fragments circulate within a closed system.

In Celmins’s drawing practice, the rendering of photographic records of deserts and galaxies was preceded in the late 1960s by drawings of lunar surfaces. These earlier works were based on widely published photographs from the Soviet Union’s 1966 space mission Luna 9. As Cécile Whiting has stressed in relation to this series: ‘The drawings also mimic the format of a photographic print, by including a thin white border along all four sides of the paper … Duplicating photographs of the moon with machinelike fidelity, Celmins ensured that her lunar drawings themselves assumed the appearance of photographs.’37

This foregrounding of photographic mimicry can also be seen in the later deserts and galaxies, where the drawings’ purposefully irregular relationship to the framing white paper takes on a heightened role in the complication of flat space. Engaging with the much broader theoretical framework of mimicry helps to complicate a straightforward understanding of illusionism or trompe l’oeil. French writer Roger Caillois’s landmark essay, ‘Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia’, published in French in the surrealist journal Minotaure in the 1930s, is a useful touchstone. Analysing the scientific data and observations concerning the camouflage mechanisms amongst insects and other creatures, Caillois concluded that environmental mimicry is not, in fact, a defensive function, but rather ‘an exaggeration of precautions’ on behalf of the creature as potential prey.38

Caillois goes on to assert that with mimicry, ‘what is involved is a disturbance in the perception of space … It is with represented space that the drama becomes specific, since the living creature, the organism, is no longer the origin of the coordinates, but one point among others; it is dispossessed of its privilege and literally no longer knows where to place itself.’39

In art historian Margaret Iversen’s reading, this mimicry process amounts to ‘a kind of death drive in which the organism loses its integrity and is swallowed up by space’.40

Celmins’s twinned sites of the desert and galaxy certainly appear hostile to subject placement and individuation, instead inviting a feeling of placelessness, a void created by too much space. In Untitled (Desert–Galaxy) the disorientating depiction of two apparently boundless spaces within the tight configuration and definite rectangular limits of the format and structure of the drawing itself renders mimicry’s loss of integrity in a palpable sense. However, in this work, what is swallowed up by space is not an individual subject. It is photography that is swallowed up by the space of drawing, thereby losing its integrity through an incremental (and partial) process of mimicry. The language of mimicry helps to complicate the principal photography-drawing axis of Celmins’s practice, circumventing the requirement to talk exclusively in terms of representation, illusionism, or visually skilful ‘trickery’. To mimic is not to replicate unquestioningly, but rather to expose photography to quite substantial pressure.

One of the reasons I used images at all was that I gave up color and I didn’t want to invent little marks. I was interested in working with space and flatness. The image has an illusionistic quality that is built into it. But it is not done by my manipulation of the image. All the manipulation I do has to do with flatness.41

This statement by the artist, made in 1979, reinforces the priority for Celmins of probing and testing the flat drawing surface, while also confirming the swallowed status of photography within her work. Despite the interest in spatial considerations, there is clearly no wish to posit illusionism as a critical concern; it is a secondary by-product of the consumed photograph. As David Musgrave has said of his own practice, which is similarly focused around drawing as it engages with other formal elements and mediums: ‘Illusion can expose the complexities of our relationship with form and material … But I’d prefer the work to be seen to be about fiction rather than illusion, because I’m not trying to fool anybody. You can see how it’s done, or at least find out fairly easily – if the fact that something isn’t what it appears to be doesn’t become part of the experience, then the work has failed.’42

This sentiment articulates very closely the relationship to illusionism we see in Celmins’s work, in which empirical photographic records, direct representation and rational, skilled drawing are stained by the doubt of fictive possibilities.

To reject the invention of ‘little marks’ is to reject the gamut of post-Pollock expressive gesture and instead embrace the photographic model as an alternative framework for drawing: one with exacting stipulations for any marks made on the paper surface. The photograph’s inherent representational qualities are not enhanced or foregrounded by the artist, but merely re-simulated. Drawing becomes a fixed site, rather than an evolving, intuitive or experimental line or mark. Rather than drawing that is active and doing – whether that action is explanatory and clarifying, an expulsion of energy, or repetitive movement tending towards solipsism – I want to argue that this drawing is almost entirely passive and still. And further, I hope to have argued, this drawing is still because its origins reside in, or are wholly dependant upon, photography – a foreign element contaminating unmediated expression and preventing decisive linear action. When there is a contaminant like photography involved, all notions of schematic clarity, preparation, or autographic function in drawing are discarded summarily. Raw ideation is compromised by an uncomfortable amount of sensuality and polish, with the drawing brought to an intense level of execution and finish. If the working drawing exists, as Mel Bochner has suggested, as the ‘residue of thought’, what Celmins does with the medium of drawing is to produce within it and from it a different kind of residue, with a different sort of temporality in play: a more distanced, mediated residue or trace.43

In doing so her practice directly confronts what critic Stuart Morgan has called ‘that vague word finish: not a description of surface but rather a measure of the degree of closure, completeness and apparent potential for independence an image has achieved.’44

It seems correct to say of Untitled (Desert–Galaxy) that it resides in a sealed state of utter completion. Celmins represents a counterpoint to repeated art historical interpretations of drawing as a radically incomplete process. Her drawing is instead smoothed over and finished as a medium and as idea; disavowing haphazard or random interventions in a zone of work which is subject to the strictures of control and watchfulness.

Things can become more powerful, more potent as ideals, when they are illusory. Our drives are distorted and made dangerous, as played out in the mythic struggles of Chinatown. It is when the illusion is pushed to breaking point that it is revealed in all its marvellous, perilous facture. The trompe l’oeil of Bikini unravels to expose a thread of insistent, productive doubt in the construction of later works like Untitled (Desert–Galaxy). Vija Celmins’s particularly finished and insistent exploration of the limits of graphite on paper brings forth an intimately scaled vision of something sealed and unreachable, conjuring up a scene of temporal suspension, and insisting upon the concept of the work as an inert fiction.