In January 1789, during the first madness of King George, Francis Willis, the Lincolnshire mad-doctor treating him, was called to a parliamentary committee to explain his methods which had been reported as being both amateurish and intimidatory. The King had apparently been allowed to use a cut-throat razor to shave himself even during periods of disturbance. One of Willis’s examiners was the Rt. Hon. Edmund Burke, who, we are told,

was … very severe on this point, and authoritatively and loudly demanded to know, ‘If the royal patient had become outrageous at the moment, what power the Doctor possessed of instantaneously terrifying him into obedience.’ ‘Place the candles between us, Mr. Burke,’ replied the Doctor, in an equally authoritative tone – ‘and I’ll give you an answer. There Sir! by the EYE! I should have looked at him thus, Sir – thus!’ Burke instantaneously averted his head, and, making no reply, evidently acknowledged this basiliskan authority.1

Burke, it seems, was already finding less pleasure than he had once believed there was to be found in the tremors of fear.

Willis’s application of ‘the eye’ to lunatics, and Burke’s assumption that they regularly required ‘terrifying … into obedience’, were standard features of the eighteenth-century mad-doctor’s therapeutic kit.2 That range of treatments had in fact dramatically shrunk since Elizabethan times. The political, religious and medical élites’ profound aversion to enthusiasm had led to an insistence upon interpretations of mental illnesses that totally eschewed the traditions of demonic possession, and to the rejection of all the astrological and para-magical interventions which were still current in the seventeenth century. Michael Macdonald concluded his famous book on seventeenth-century English psychiatry, Mystical Bedlam, with this assessment: ‘The rise of psychological medicine [during the eighteenth century] has often been represented as a saga of scientific progress. It was not. It was instead a tale of religious hatred, political conflict, social antagonism, and, at last, intellectual advancement.’3 The élite acceptance of a psychological understanding of madness, underwritten by John Locke’s labelling of lunacy as reasoning from wrong premises, opened the way, in the eighteenth century, to a phase of mental doctoring during which the physician felt bound directly to manipulate the patient’s feelings using all the ingenuity they could muster. Lunatics continued to be bled, vomited and purged according to the ancient tradition of the anti-inflammatory regime which would dilute the damaging excesses of their vital fluids.4 But now their minds, too, would be worked upon with comparable interventions, interventions informed by the categories of eighteenth-century psychology, among them the sublime.

Let us recall that the sublime was essentially healthy. The eighteenth-century debates around the aesthetics of transporting sensations were, as Frances Ferguson stressed in her book Solitude and the Sublime, conducted precisely in order to define an appropriate place for the sublime in a shared culture. For Ferguson, later Romantic emphases on uncompromised subjectivity obscured this point until recent theory, especially Deconstruction, reduced the arrogant subject back down to size.5 To be alive to the massive possibilities that seem to exist beyond one’s capacity really to grasp them might be an exercise in existential humility. (And, Burke added in his Enquiry, the sublime offers a sort of work-out for the finer fibres of the nervous system).6 To actually start believing in the possibility of living the sublime was madness. Žižek, paraphrasing Kant, explains that the sublime prompts astonishment, a reasonable enthusiasm, as opposed to the ‘insane visionary delusion that we can immediately see or grasp what lies beyond all bounds of sensibility’.7 Such confusion is conventionally attributed to the mad, but in a political context was attributed also by Burke to the French Revolution, and by Žižek and Lyotard to the totalitarian ideologies of the twentieth century.8

William Hogarth

A Rake’s Progress (plate 8)

(1735–63)

Tate

So the mad had lost sight of the sublime, so to speak, by entering into it. They therefore required a new, stronger dose of the sublime to be administered by their doctors, one strong enough to recalibrate their sense of proportion so that they could take up once again a more realistic relationship to the world. At its crudest, such a socialising therapy might take the form of public humiliation, as at Bethlem – Britain’s oldest public madhouse – from which the paying public were only excluded in 1770 when their numbers became too great to manage.9 Hogarth famously referred to this practice of the lunatic being put on show (fig.1), a practice that has, since the nineteenth century, been represented as barbaric. That it was, in part, intended to be good for the patients was forgotten.

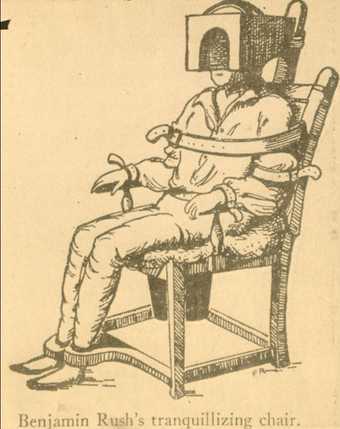

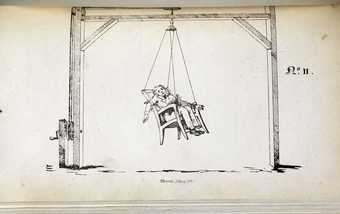

Shock therapies – another form of medicine with an ancient pedigree – were regularly recommended. The violent shower was so especially popular as to suggest an association with the contemporary iconography of the sublime deluge (fig.2). Variations on this theme included the ‘bath of surprise’, a cold water bath entered by the unsuspecting patient via a trap-door in a corridor.10 There were also machines which sought to repossess the patient’s mind through total control of their body. Early in the nineteenth century the American Benjamin Rush designed this elaborate chair to overwhelm every motion and sense of the raving patient (fig.3).11 Chairs were also used to contain the patient within a rotatory machine in which they were swung around as if on a merry-go-round (fig.4), another ancient therapy. The chair indeed takes on a substantial iconographic presence within psychiatry of this period, comparable to the role of the couch in the later iconography of pychoanalysis. Willis had a specially made restraining chair for King George. A loyal courtier recorded that ‘When it was first brought into the Room to be made use of, the Poor King is said to have eyed it with some degree of Awe’, and with bitter irony dubbed it his ‘Coronation Chair’.12

Fig.3

Benjamin Rush

‘Tranquillizing’ Chair 1811

Engraving in Philadelphia Medical Museum

© University of Pennsylvania Archives

Fig.4

Rotatory Machine

From Alexander Morison, Cases of Mental Disease, 1828

By permission of The British Library (1172 H6)

The rotatory chair was particularly advocated by Joseph Mason Cox, who owned a large private asylum near Bristol, and whose Practical Observations on Insanity contains some of the more flamboyant techniques to be recommended in the literature of the period. Cox suggested various elaborations on the use of the swinging chair; for instance, it might be ‘employed in the dark, where, from unusual noises, smells, or other powerful agents, acting forcibly on the senses, its efficacy might be amazingly increased’.13 For patients particularly resistant to such interventions, Cox recommended to the alienist an even more daring strategy. If the patient could not be recalled from his or her world of sublime delusion, then the doctor must go in and get them. This meant acting up to the delusional drama, the doctor assuming a role within it.

It is certainly allowable [Cox suggested] to try the effect of certain deceptions, contrived to make strong impressions on the senses, by means of unexpected, unusual, striking, or apparently supernatural agents; such as after waking the party from sleep … by imitated thunder or soft music … combatting the erroneous deranged notion, either by some pointed sentence, or signs executed in phosphorus upon the wall of the bedchamber, or by some tale, assertion, or reasoning by one in the character of an angel, prophet, or devil.14

There are plenty of comparable cases recorded in classical and early-modern literature, and in the latter cases particularly the notion of the physician as performer seems to have been associated with materialist medicine seeking alternatives to narratives of supernatural possession. The doctors’ performances are undertaken as pure charade, any ‘supernatural agents’ having no actual role in any part of either the delusions or the affect that will form part of their cure.15

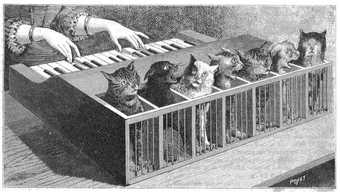

Fig.5

Poyet

Cat-Keyboard

(Katzenklavier)

Wood engraving from La Nature, 1883, p. 283

Bibliothèque du Cnum 4° KY 28.

© Cnum – Conservatoire Numérique

Cox’s Practical Observations were first published in 1804. In the previous year there appeared the classic text of German ‘romantic psychiatry’, Johann Christian Reil’s Rhapsodies on the Application of Psychological Methods of Cure to the Mentally Disturbed.16 Reil, in seeking to invigorate psychiatry (a word he himself coined) with the blend of aesthetics and the natural sciences of the new Naturphilosophie, improvises on the theme of the therapeutic beast.17 Why not try plunging the lunatic into a bath full of live eels, he suggests – this is bound to prompt a reaction. Or what about showing them a Katzenklavier, or cat-clavichord (fig.5), an instrument played by pressing keys attached to nails which in turn strike the tails of a series of cats arranged with care so as to miaow in tonally sequenced pain. Now at this point the sublime has evidently made one of its periodic forays into the ridiculous. That the cat-clavichord was ever really used in any kind of clinic must be doubted, and historians alive to the professional hyperbole of mad-doctors have also raised eyebrows at all the ‘surprise baths’ and other psychiatric apparatus supposedly in use in Britain.18 It seems to me that what we have here is the adoption by the mad doctors of the sublime aesthetic at two levels. First, there is the clinical call upon the sublime to help compress lunacy back within bounds; and, second, there is the literary rehearsal of the sublime for the purpose of associating the socially compromised mad-doctoring trade with a prestigious discourse of polite philosophy. Tropes from classical and early modern sources are recovered, secularised and recycled in a kind of literary mental science – a philosophical model of how psychiatry might be.19 There is an exclusive attention upon the effects of the sublime per se rather than on any really existing sublime object, and we are therefore looking at an example of what Ashfield and de Bolla describe as characteristic of the later eighteenth-century trajectory of the sublime, where ‘writers begin to become increasingly occupied with the discursive production of sublimity’.20

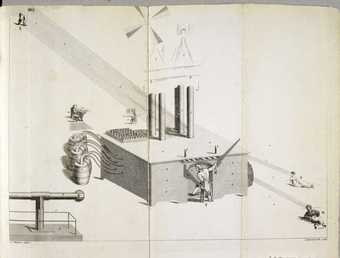

Fig.6

The Air Loom

From Haslam, Illustrations of Madness, p.181

By permission of the British Library (1191 I 7)

I should like now to move to a case in which the patient has more presence – the relatively well-known one of James Tilly Matthews. A tea merchant of Radical sympathies, Matthews made several trips to Paris during the Revolution and convinced both himself and (at least temporarily) some leading political figures in London and among the Girondins, that he was in a position to negotiate peace between Britain and France. After imprisonment in Paris, Matthews eventually returned home in an agitated state and was confined to Bethlem after shouting abuse in the House of Commons in 1796.21 The air loom (fig.6) was the state-of-the-art scientific apparatus, located in a cellar near the London Wall around the corner from Bethlem itself, to which Matthews attributed the machinations of British politics. According to his detailed description and drawing of the loom, it was fed from a range of disgusting natural effluvia stored in barrels, using pneumatic technology to project mesmeric beams at its victims, whose minds and bodies could be controlled in a terrifying myriad of ways.

At Bethlem, Matthews was a kindly and gentle patient whom many, not least his own family, felt had been wrongly treated. It was the family’s most concerted effort to force his release in 1809 that prompted the creation of this image of the air loom. Bethlem was nominally overseen by Dr Thomas Monro, who had inherited his position of Visiting Physician through his father and grandfather. But Monro was more interested in the patronage of watercolour artists, not least Turner for whom he provided the opportunity thoroughly to study the work of one of his patients, John Robert Cozens, a crucial relationship for Turner’s understanding of the sublime (fig.7). (The link with Monro may have come through Turner’s mother, who died in Bethlem in 1804).22 The hospital’s daily medical work was in practice carried out by its Apothecary, John Haslam, a brilliant and ambitious mad-doctor without formal qualifications who was on a mission to demonstrate his superior expertise in the management of lunacy compared to that of the élite society physicians such as Monro on one hand, and the authors of ‘DIY’ handbooks of psychiatry, such as Cox, on the other. Only extensive first-hand experience of hundreds of patients such as Haslam himself had obtained at Bethlem could qualify one to speak with authority. But in 1809, Haslam’s verdict on Matthews – that his madness was incontrovertible albeit unobtrusive except where politics were concerned – was contradicted by two MDs testifying on behalf of Matthews’ family. Although Matthews was in the event never released, Haslam, goaded to a fury of professional pride, published in 1810 a book that sought to demonstrate thoroughly both the madness of Matthews and the incompetence of the typical MD to diagnose that condition. He called it Illustrations of Madness: Exhibiting a Singular Case of Insanity, and a No Less Remarkable Difference in Medical Opinion. It is a psychiatric classic in that it is often pointed to as providing the first full description of what was later termed schizophrenia, and in that it dramatises so compellingly the struggles of both doctor and patient to be taken seriously.

Fig.8

Rod Dickinson

The Air Loom, A Human Influencing Machine 2002

Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle © The artist

Haslam’s Illustrations of Madness contained an engraved plate, based on Matthews’s own drawing, of the air loom (fig.6).23 The loom’s physical power, its range of influence, its hidden location and mysterious operation, signal it as aspiring to the sublime, while the image of the loom, designed to demonstrate that the object itself cannot exist, is occupied exclusively ‘with the discursive production of sublimity’. Haslam wishes to refute Matthews’s explanations of the political world through a reductio ad absurdum, which is to say a reductio ad mundum – to make an attempt to physically materialise the air loom which he knows can only end in failure. (Although among Matthews’s modern champions has been the artist Rod Dickinson who in 2002 actually reconstructed the air loom life-size in Newcastle, fig.8)24 Haslam’s rhetoric is to pit his own sober science and statistics against the sublime, an aesthetic category now exhausted, worn out not least by the French Revolution during which Matthews himself had lost his reason. Haslam was contemptuous of the remedies for lunacy advocated by Cox and others. For him, these philosopher-doctors took the lunatic’s symptoms too seriously, entered too much into their delusional worlds.25 Haslam insisted – like plenty of psychiatric reformers after him – on the study of the medical causes of insanity: to become distracted by picturesque or dramatic symptoms was a blind alley.26 And here of course is the rich irony of Haslam’s career: he is now best remembered precisely for recording such illustrations of madness.

Haslam’s arrogant dismissal of just about every other British opinion concerning lunacy extended also to the new experiments being made in ‘moral therapy’. Pioneered by Quakers from the 1790s, this new ideal in caring for the mentally ill embraced the tradition of engaging with the delusions of patients so disapproved of by Haslam and added to it a zero-tolerance approach to the physical punishment or restraint of patients.27 The entire project was underwritten by an Evangelical rhetoric of love and hope, but, wedded as it soon became to the state’s determination to remove the unstable from society and ‘warehouse’ them in asylums, moral therapy and the non-restraint movement wear, for Foucauldian historians, the smiling face of a malignant and coercive apparatus. Certainly, the new doctrine of loving confinement brooked no opposition, swiftly crushing those side-tracked by the new consensus.28 Bethlem, as the symbol of the psychiatric ancien régime, found itself, despite Haslam’s claims as a moderniser, in the firing line in 1814. The Quaker MP Edward Wakefield forced his way into the collapsing hospital and made the country shudder with his reports of what he saw there.29

Crucial to the impact of his evidence was the reproduction in the press of a drawing of a Bethlem patient commissioned by Wakefield from the landscape artist George Arnald.30 James Norris was an American marine and, according to Haslam, a ferociously dangerous patient, whose unusually jointed wrists meant that ordinary manacles could not restrain his violent impulses. This special harness was therefore constructed especially for him. Here, in the hands of the lunacy reformers, the structure of fear has been turned inside out. Rather than the patient being improved through terror, now the psychiatric profession will be reformed through the dismay artfully generated in the public by imagery such as this.

Fig.9

After Richard Dadd

Detail: Morison Prize Certificate for Female Attendants 1865

Engraving

© Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

Fig.10

After Richard Dadd

Detail: Morison Prize Certificate for Female Attendants 1865

Engraving

© Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh

As a coda I should like to jump forward to the 1860s and to one further image by a psychiatric patient facilitated by a doctor (fig.9). This is the certificate awarded by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh to recipients of the Morison Prize, asylum attendants who had demonstrated humane attention to their patients over long periods of service.31 The award was named after Alexander Morison who had been another Bethlem physician and a patron of Bethlem’s most famous Victorian inmate, the painter Richard Dadd. In 1864 Dadd was moved to the new State Criminal Lunatic Asylum at Broadmoor from where he must have sent Morison the two pairs of designs used for the male and female versions of the certificates (fig.10). In each, an image from the Elizabethan stage forms the ‘before’, and a pair of calmly productive figures forms the ‘after’ – one of these is the patient and the other the attendant, but it is not at all clear which is which. Dadd’s designs appear to follow Victorian orthodoxy in celebrating the suppression of the lonely, sublime maniac and the patient’s entry into socialising moral therapy. But Dadd’s images seem also to prophesy the development within asylum medicine of the new genus of psychosis – the schizoid paradigm that was to inform the psychiatric profession, and the anti-psychiatry movements, of the twentieth century.32