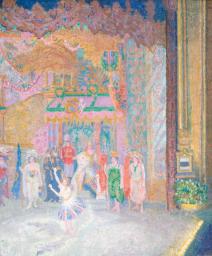

Walter Richard Sickert Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford 1892

Walter Richard Sickert,

Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford

1892

The music hall performer Minnie Cunningham was introduced to Walter Sickert by the poet Arthur Symons at the Tivoli music hall on the Strand. This painting’s composition reveals the combined influences of the French painter Degas in its subject matter and the American painter Whistler in its use of paint, shallow pictorial space and profile format. Cunningham’s vermillion dress glows vibrantly against a dark background in the low lighting of the theatre.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Minnie Cunningham

1892

Oil paint on canvas

765 x 638 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘W. Sickert.’ in black paint bottom right

Purchased (William Rutherford Bequest and Grant in Aid) 1976

T02039

1892

Oil paint on canvas

765 x 638 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘W. Sickert.’ in black paint bottom right

Purchased (William Rutherford Bequest and Grant in Aid) 1976

T02039

Ownership history

Sir Augustus Daniel (1866–1951), probably from the artist; bought at the Leicester Galleries, London, in 1951 by Sir Peter Pears (1910–1986); Roland, Browse & Delbanco, London, 1976 when purchased by Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1892

New English Art Club: Winter Exhibition, November–December 1892 (91, as ‘Miss Minnie Cunningham Sings, “I’m an Old Hand at Love, Though I’m Young in Years”’).

1895

Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Walter Sickert and Bernhard Sickert, Van Wisselingh’s Dutch Gallery, London 1895 (11, as ‘Miss Minnie Cunningham’).

1951

The Collection of Paintings and Drawings of the Late Sir Augustus Daniel, K.B.E., 1866–1950, Leicester Galleries, London, June 1951 (55).

1955

Some 20th Century Paintings from the Collection of Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten, Arts Council, London 1955 (30).

1973

Sickert, Fine Art Society, London, May–June 1973, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh, June–July 1973 (15, reproduced).

1986

New English Art Club: Centenary Exhibition, Christie’s, London, August–September 1986 (98, reproduced).

1990

W.R. Sickert: Drawings and Paintings 1890–1942, Tate Gallery, Liverpool, March 1989–February 1990, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1990 (1, reproduced).

1990

From Beardsley to Beaverbrook: Portraits by Walter Richard Sickert, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, May–June 1990 (4, reproduced).

1992–3

Sickert: Paintings, Royal Academy, London, November 1992–February 1993, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, February–May 1993 (14, as ‘Miss Minnie Cunningham’, reproduced).

1998

James McNeill Whistler, Walter Richard Sickert, Fundación ‘la Caixa’, Madrid, March–May 1998, Museo de Bellas Artes, Bilbao, May–July 1998 (71, reproduced).

2005

Walter Richard Sickert: The Human Canvas, Abbott Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, July–October 2005 (3, reproduced).

2005–6

Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris 1870–1910, Tate Britain, London, October 2005–January 2006 (62, reproduced).

2007

Il Settimo splendore: La Modernità della malinconia, Palazzo della Ragione, Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Verona, March–July 2007 (86, reproduced).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (11, reproduced).

References

1892

Star, 19 November 1892.

1892

Weekly Despatch, 20 November 1892.

1892

Birmingham Gazette, 21 November 1892.

1892

‘The New English Art Club’, Daily Graphic, 21 November 1892.

1892

Sheffield Telegraph, 21 November 1892.

1892

Standard, 21 November 1892.

1892

Daily News, 23 November 1892.

1892

Academy, 26 November 1892.

1892

Black & White, 26 November 1892.

1892

Gentlewoman, 26 November 1892.

1892

Lady’s Pictorial, 26 November 1892.

1892

Life, 26 November 1892.

1892

National Observer, 26 November 1892.

1892

Spectator, 26 November 1892.

1892

Northern Whig, 30 November 1892.

1892

Morning Post, 1 December 1892.

1892

‘The New English Art Club – Some of the Pictures’, Pall Mall Budget, 1 December 1892, reproduced as a wood engraving.

1892

Builder, 3 December 1892.

1892

Land and Water, 3 December 1892.

1892

‘The Glasgow School’, Speaker, 10 December 1892.

1892

Sunday Sun, 11 December 1892.

1895

Idler, March 1895, reproduced p.173.

1898

George Moore, Modern Painting, London 1898, pp.204–5.

1930

Alfred Thornton, ‘Walter Richard Sickert’, Artwork, vol.6, no.21, Spring 1930, p.13.

1938

Alfred Thornton, The Diary of an Art Student of the Nineties, London 1938, p.33.

1962

Roland Pickvance, ‘The Magic of the Halls and Sickert’, Apollo, vol.77, April 1962, p.111.

1966

Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1966, p.63.

1973

Wendy Baron, Sickert, London 1973, pp.31, 304, no.46, reproduced pl.37.

1973

Paul Overy, ‘The Novelist Side of Sickert’, Times, 6 June 1973, reproduced p.11.

1977

Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1977, p.11, reproduced p.10.

1979

Tate Gallery Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1976–8, London 1979, pp.132–3.

1988

Hugh David, The Fitzrovians: A Portrait of Bohemian Society 1900–55, London 1988, p.69.

1988

Richard Shone, Walter Sickert, Oxford 1988, reproduced pl.12.

1990

Simon Wilson, Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion, London 1990, reproduced p.97.

1992

Anna Gruetzner Robins, ‘Sickert “Painter-in-Ordinary” to the Music-Hall’, in Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, pp.18–22.

2001

David Peters Corbett, Walter Sickert, London 2001, p.14, reproduced fig.6.

2004

Vision 2004, Lakeland Arts Trust 2004, p.2, reproduced.

2005

Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, pp.195, 197.

2006

Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, p.27, no.94 reproduced.

Technique and condition

Sickert chose a coarse-textured canvas with double-weave threads for this painting. He purchased the standard three-quarter size canvas pre-primed from the artists’ colourmen Charles Roberson. The cloth has off-white priming, which has been evenly applied and retains the strong weave texture of the canvas, providing a preparatory surface with a heavy tooth. Sickert applied his own thin light red opaque oil ‘priming’ layer over the white primer and a further thin layer of dark paint on top of the red. This darker layer appears throughout much perhaps all of the painting and splashes of the paint extend onto the tacking edges. The figure is painted thinly in red oil paint, possibly with the addition of other resinous media. The background is painted similarly in dull reds and greens to achieve a low tone contrast with the red and in order to make it look brighter. It is tempting to think that Sickert followed the advice of his mentor Edgar Degas and achieved the intensity of colour purely through the tonal contrasts: ‘to surround a patch of, say, Venetian red, so that it appears to be a patch of vermilion’.1

In fact, Sickert selected pure vermilion mixed with a little lead white to achieve the desired colour. The dark underlayers also now appear much stronger thus heightening the contrast between light and dark. Much of the painting was executed using ¼ inch hogshair brushes and the brushmarking is preserved in the dried paint film. The face has been rubbed down and reworked, exposing in the form of the canvas weave the off-white commercial priming, the artist’s light red primer and the dark underpaint in concentric rings around the tops of the canvas threads. The painting was probably originally varnished and does not appear to have been cleaned; there is a thin layer of soft resin varnish applied over the surface.

Stephen Hackney

July 2004

Notes

How to cite

Stephen Hackney, 'Technique and Condition', July 2004, in Robert Upstone, ‘Minnie Cunningham 1892 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Born in Birmingham in the West Midlands, Minnie Cunningham was a ‘serio-comic’ singer and dancer in the music halls (fig.1). Her career began around 1888, during which year she performed at a number of London music halls, including the Oxford, the Parthenon and Collins’, being described as a ‘youthful singer and dancer’.1 Owing to confusion with an American actress of the same name born in 1855 there has formerly been a belief that she was, when Sickert painted her, a middle-aged performer,2 adding an extra layer of irony and salaciousness to the songs she sang about herself in the character of an innocent schoolgirl. But, in fact, Cunningham was a young woman in her early twenties when Sickert met her in 1892, and was described by the poet Arthur Symons in a letter to a friend as ‘very pretty, very nice, very young’.3

Minnie Cunningham

Print

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.1

Minnie Cunningham

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Gatti's Hungerford Palace of Varieties, Second Turn of Katie Lawrence c.1902–3

Oil paint on canvas

381 x 470 mm

Yale University Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Yale University Art Gallery

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Gatti's Hungerford Palace of Varieties, Second Turn of Katie Lawrence c.1902–3

Yale University Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Yale University Art Gallery

Cunningham was successful, and shared the bill with such stars as Ada Reeve, Marie Lloyd and Katie Lawrence, all of whose acts were also painted by Sickert (see, for example, fig.2).4 She adopted the stage persona and dress of a teenage girl and sang what Marie Lloyd described as ‘romping schoolgirl songs’.5 Like other such serio-comic performers, such songs were laced with sexually provocative double-entendres that circumvented the obscenity laws. Cunningham wrote many of her own songs, with such titles as The Art of Love, It’s Not the Hen that Cackles the Most that Lays the Largest Egg,6 Did You Ever See a Feather in a Tom Cat’s Tail? and Bridget and Mike, An Irish Serenade.7 When Sickert exhibited his picture of Minnie Cunningham for the first time at the New English Art Club in 1892, his title specified that she was singing I’m an Old Hand at Love, Though I’m Young in Years.

Sickert was introduced to Cunningham by the symbolist poet and music-hall critic Arthur Symons (1865–1945). Infatuated with Cunningham, Symons wrote to Ernest Rhys in 1892, ‘I need scarcely say I have fallen in love with a new dancer. This time it is Minnie Cunningham.’8 Reviewing her performances at the Tivoli in the Star, Symons drew particular attention to Cunningham’s ability as a dancer, describing it as ‘an invention of absolute originality ... the visible caprice, an instinctive poetry of movement, a faultless and exceptional rhythm’.9 Symons was moved to compose a poem about Cunningham’s dancing, which he published in the Sketch:

Skirts like the amber petals of a flower,

A primrose dancing for delight

...

A rhythmic flower whose petals pirouette

...

So, in the smoke-polluted place,

Where bird or flower might never be,

With glimmering feet, with flower-like face,

She dances at the Tivoli.10

A primrose dancing for delight

...

A rhythmic flower whose petals pirouette

...

So, in the smoke-polluted place,

Where bird or flower might never be,

With glimmering feet, with flower-like face,

She dances at the Tivoli.10

Symons took Sickert to see Cunningham perform at the Tivoli in the spring of 1892, and later he introduced the two:

Walter Sickert wanted to paint Minnie Cunningham who danced at the Tivoli; so on a certain Sunday I took him with me to where Minnie lived with her mother somewhere I think in Islington; she had made up [i.e. had on stage make-up], on account of Sickert; and there I heard what I have always hated the dreary sound of the church bells.11

Evidently Sickert, too, was captivated, and asked Symons to get Cunningham to agree to be painted by him. In a letter to Herbert Horne dated 25 May 1892, Symons wrote of Cunningham:

I am glad to learn that she has done my bidding and given a sitting to Sickert. She complains a little that he has made her ‘too tall and thin’.12

Tivoli Music Hall, The Strand, London c.1910

Colour-tint postcard

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.3

Tivoli Music Hall, The Strand, London c.1910

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

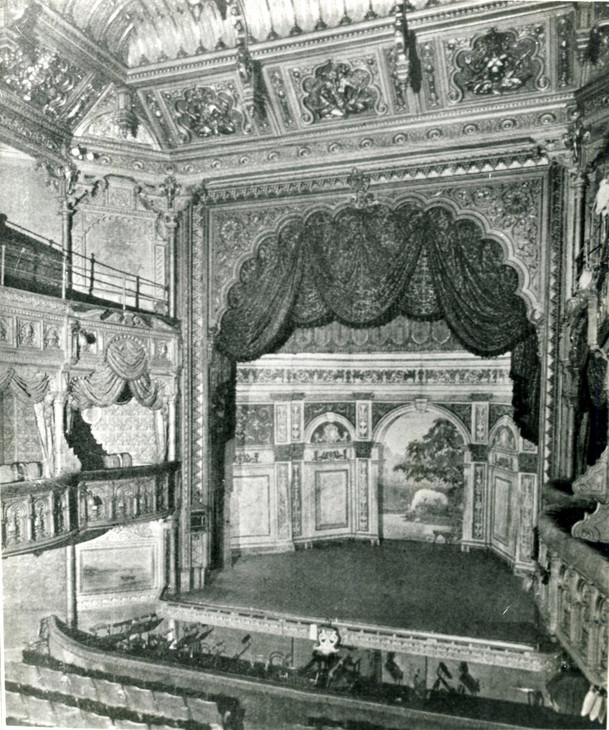

The Interior of the Tivoli Music Hall, London c.1910

Photographic print

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.4

The Interior of the Tivoli Music Hall, London c.1910

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

This evidence confirms with certainty that the date of Tate’s picture is 1892.13 Traditionally, Minnie Cunningham has been dated in Tate catalogues and elsewhere to c.1889.14 It also suggests that the picture is almost certainly a record of Cunningham’s association with the Tivoli on the Strand (figs.3–4), rather than the Old Bedford in Camden Town, which has been a feature of its title in the Tate collection since its acquisition in 1976.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Music Hall or The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror 1888–9

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 510 mm

Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts. Donation Jacques-Emile Blanche, 1922

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Musées de la Ville de Rouen. Photographie C. Lancien, C. Loisel

Fig.5

Walter Richard Sickert

The Music Hall or The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror 1888–9

Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts. Donation Jacques-Emile Blanche, 1922

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Musées de la Ville de Rouen. Photographie C. Lancien, C. Loisel

Sickert’s music-hall pictures of the 1880s concentrate predominantly on the performers, while those in the later 1890s generally focus on the audience or architecture. As the art historian Wendy Baron has noted,18 Minnie Cunningham was the only music hall picture Sickert made between 1890 and 1894, a period when he was concentrating more on making portraits (see Tate N03181).

Evidently Sickert greatly admired Cunningham and she inspired him to write what is perhaps his only poem:

Evidently Sickert greatly admired Cunningham and she inspired him to write what is perhaps his only poem:

When I glance through the Entr’acte’s roll of fame,

My serio-comic sweetheart, shall I see

That many countries sever you and me?

Or worse, the legend underneath your name

‘In Melbourne pantomime the leading dame’?

And, bowing to an agent’s stern decree,

A twelve month miss the fairy filigree

Of whirling lace, the primrose that became

Your sentimental rhymed proprieties,

The quaint recurring couplet’s silly scream,

The click and shuffle of the dusty stage

Of dancing feet, the limelight’s magic gleam?

Are you at Deacon’s, Gatti’s? Ah, kind page!

The Peckham Palace of Varieties!19

My serio-comic sweetheart, shall I see

That many countries sever you and me?

Or worse, the legend underneath your name

‘In Melbourne pantomime the leading dame’?

And, bowing to an agent’s stern decree,

A twelve month miss the fairy filigree

Of whirling lace, the primrose that became

Your sentimental rhymed proprieties,

The quaint recurring couplet’s silly scream,

The click and shuffle of the dusty stage

Of dancing feet, the limelight’s magic gleam?

Are you at Deacon’s, Gatti’s? Ah, kind page!

The Peckham Palace of Varieties!19

Related works and inspiration

A drawing of Minnie Cunningham was published as a wood engraving in the Idler in March 1895, signed ‘Sickert’ on one side and the name of the wood engraver on the other;20 essentially it is a reproduction of the painting. Sickert also made a second oil portrait, closely related to Tate’s picture. This shows Cunningham in a very similar composition, with an identical palette of colours but more sketchily painted (fig.6).21 In this work Cunningham holds her arms aloft, perhaps in the act of dancing, and wears a sash-waisted dress albeit still scarlet. Slightly smaller than the Tate painting (610 x 457 mm), it was acquired by Sickert’s friend Sidney Starr, the London impressionist painter.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Minnie Cunningham c.1892

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 457 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo courtesy of Wendy Baron and Jonathan Clark & Co.

Fig.6

Walter Richard Sickert

Minnie Cunningham c.1892

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo courtesy of Wendy Baron and Jonathan Clark & Co.

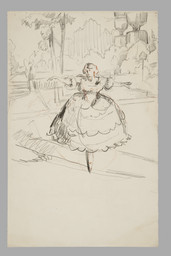

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

It's not the Hen that Cackles the Most that Lays the Largest Egg c.1892

Crayon and pencil on squared paper

150 x 98 mm

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © National Museums Liverpool

Fig.7

Walter Richard Sickert

It's not the Hen that Cackles the Most that Lays the Largest Egg c.1892

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © National Museums Liverpool

There are three recorded drawings of Minnie Cunningham. A head and shoulders work in pencil depicting her in profile is similar in intention to Tate’s painting, and presumably made around the same time, perhaps in preparation for the work (c.1892, private collection).22 A crayon and pencil drawing on squared paper, which Sickert inscribed ‘It’s not the hen that cackles the most | That lays the largest egg’, the title of one of Cunningham’s most famous songs (fig.7),23 is evidently related to the painting with arms aloft. Lastly, there is a small drawing of Cunningham’s face, again in profile (c.1892, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool).24 The consistent profile format of all these drawings demonstrates that from the beginning Sickert envisaged this approach. Sketches of Cunningham were exhibited in Paintings and Drawings by Walter Sickert in May 1912 at the Carfax Gallery (67) and Studies and Etchings by Walter Sickert in March 1913 at the same venue (18d), but it is not known if they relate to any of the surviving material.

Ultimately, Sickert’s devotion to painting music hall subjects in the 1880s and 1890s was inspired by his friend Edgar Degas. In Paris, Degas and Edouard Manet’s pictures of café concerts had been greeted with some interest, and even respected Salon painters such as Jean Béraud took them up as fitting subjects of urban life.25 But in Britain Sickert faced intense critical hostility when he showed Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties: Second Turn of Miss Katie Lawrence 1887–8 (believed destroyed, possibly similar to fig.2)26 at the New English Art Club in April 1888. It represented ‘the lowest degradation of which the art of painting is capable’, according to the Builder, while the Artist believed it symptomatic of ‘the aggressive squalor that pervades to a greater or lesser extent the whole of modern existence.’27 Even other members of the New English Art Club were shocked, and the artist Stanhope Forbes angrily scorned the picture as ‘tawdry, vulgar and the sentiment of the lowest music hall’.28

No painter before Sickert had dared to consider the music hall as a fitting subject for art, and his production of such pictures was considered wilful and provocative. In Britain the music hall held distinct connotations of immorality. Many of the acts, Minnie Cunningham included, dealt in the currency of ribald, vulgar or suggestive humour, and it was just this waywardness that partly made the music hall so popular. But the halls themselves were considered dens of dissolution by the moral majority. Alcohol was served throughout performances, and volatile audiences were encouraged to join in singing the often bawdy song choruses. Additionally, many of the halls were believed to be venues where prostitutes plied their trade. The Empire in Leicester Square was particularly notorious as a place where, away from the auditorium in its promenade area, clients could meet prostitutes.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1834–1903

Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, Portrait of the Artist's Mother 1871

Oil paint on canvas

1443 x 1630 mm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.8

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, Portrait of the Artist's Mother 1871

Musee d'Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

In a sense, Minnie Cunningham draws together the two artistic influences that had exerted a profound impact on Sickert’s work, as it might be characterised as a Degas subject expressed in a Whistlerian idiom. Combining these twin inspirations might almost be seen as a cipher for Sickert’s first meeting with the French artist when he took Portrait of the Artist’s Mother to Paris for Whistler in 1883, bearing the letter of introduction to Degas that Whistler had written him.

A further level of connection is the similarity of Minnie Cunningham to a number of pictures by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. There seem to be fairly strong resonances with Toulouse-Lautrec’s theatrical lithographs, such as the standing half-profile formats of Anna Held, dans toutes ces dames au theatre (1894), Mademoiselle Marcelle Lender, Debout (1895) or Miss May Belfort (Grand Planche) (1895) with the orchestra, and most interestingly with the striking red dress print of May Belfort holding a cat (1895). This last, the art historian Richard Thomson has suggested, could potentially have come from Toulouse-Lautrec seeing Sickert’s Minnie Cunningham at the 1892 New English Art Club exhibition.31 But a red dress may have been a common attire of such performers, and to a culture versed in the nuances of what wearing such gaudy colours might represent, scarlet was a further allusion to wayward sexuality and prostitution.

Exhibition and reception

When Sickert exhibited Minnie Cunningham for the first time at the New English Art Club Winter Exhibition in 1892, press criticism was split almost equally between approval and rejection. But what is most noticeable is that in comparison with the enormous number of reviews of his portrait, George Moore (Tate N03181), exhibited the year before, comparatively few notices bothered to mention Minnie Cunningham. Most of the reviews highlighted, instead, Philip Wilson Steer’s impressionist beach scene, Boulogne Sands 1888–91 (Tate N05439).

Describing Minnie Cunningham as ‘thoroughly enjoyable and artistic’, the Birmingham Gazette judged it ‘the picture of the Exhibition’,32 and Black and White agreed it was ‘quite excellent’.33 Several of the negative reviews drew attention to what they believed was the rigid quality of the figure. ‘How inhuman and caricature-like is the result’, Life complained, ‘a pretty little girl is turned into a wooden doll’,34 while the Northern Whig protested ‘her chin is poked out, and her hand standing stiff and wooden, as if she is rehearsing a part for the clock wound up figures in The Mountebanks’.35

George Moore, surely with his own portrait of the previous year still partly in mind, wrote in the Speaker that Sickert

exhibits two portraits, both very clever and neither satisfactory, for neither are carried beyond the salient lines of character. Nature has gifted Mr Sickert with a keen hatred of the commonplace; his vision of life is at once complex and fragmentary, his command of drawing slow and uncertain, his rendering therefore as spasmodic as a poem by Browning ... Still, even the most remote intelligence should be able to gather something of the merit of the portrait of Miss Minnie Cunningham. How well she is in that long red frock – a vermillion silhouette on a rich brown background! I should be still more pleased if the vermillion had been slightly broken with yellow ochre; but then, at heart, I am no more than un vieux classique. The edges of the vermillion hat receive the glare of the footlights; and the face does not suffer from the red. It is as light, as pretty, as suggestive as may be. The thinness of the hand and wrist is well insisted upon, and the trip of the legs, just before she turns, realises, and in a manner I have not seen elsewhere, the enigma of the artificial life of the stage.36

The Spectator praised the beauty of the picture, and the possibilities of the music hall as a subject:

The swaying little figure is very graceful, and the profile, against its background of hair, lovely and tenderly drawn. It is one of the commonplaces of stupid criticism to suppose that a music-hall subject must be something ugly, chosen by a painter out of bravado. Quite apart from the fascination of stage-lighting, and the accidents of stage-colour, the fact is, of course, amusingly different. Among the various highly trained performers – dancers, singers, acrobats – beauty and grace hold the stage as well as grotesqueness and vulgarity. An artist knows how to treat all three if his range be great enough, but in a case like this there is nothing in the subject that would not delight a Botticelli.37

Most surprisingly in view of Cunningham’s popularity, at least two critics appeared to be sincere in writing about the picture as if it was not a stage scene at all but a portrait of a real child. The Birmingham Gazette described her as ‘a sweet little girl, whose beauty is refined enough to bear the glare of the brilliant crimson in which she is dressed’,38 while the Daily Graphic described

a pretty young damsel in a brilliant red cloak; a garden at night is behind her, and she appears to be illuminated by the lamplight from the open window in the front. The effect is a brilliancy almost dazzling. But what has the child done that she should be cut off abruptly at the ankles, and have her shoes hidden in the frame?39

Ownership

The first owner of Minnie Cunningham was Sir Augustus Moore Daniel (1866–1950). Director of the National Gallery from 1929 to 1933, he was a collector and connoisseur of British art and a particular supporter of Philip Wilson Steer. His collection was exhibited at the Leicester Galleries, London, in June 1951, and included pictures by a broad range of modern British artists, including Mark Gertler, William Orpen, Stanley Spencer and Henry Tonks. He appears to have been a modest buyer of Camden Town painting, and owned Harold Gilman’s Mother and Child (Auckland Art Gallery) and two pictures by Charles Ginner. The music hall must have been a particular enthusiasm, for, as well as Minnie Cunningham, Daniel also owned Sickert’s The Sisters Lloyd c.1888–9 (Government Art Collection).40

At the posthumous exhibition of Daniel’s collection at the Leicester Galleries in 1951, Minnie Cunningham was bought by the tenor Peter Pears (1910–1986). Pears was particularly known for his performances of the compositions of his partner Benjamin Britten (1913–1976), and together they formed a collection of British pictures, including works by John Craxton, Lucian Freud, Mark Gertler, Spencer Gore, Gwen John and John Piper. In addition to Minnie Cunningham, they also owned Sickert’s Santa Maria della Salute,41 and both pictures were included in the exhibition of their collection by the Arts Council in 1955. Pears sold Minnie Cunningham in 1976, following Britten’s death.

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

See Anna Gruetzner Robins, ‘Sickert “Painter-in-Ordinary” to the Music-Hall’, in Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, pp.18–22.

Arthur Symons, letter to Ernest Rhys, in Karl Beckson and John M. Munro (eds.), Arthur Symons: Selected Letters 1880–1935, London 1989, p.95.

See Richard Shone in From Beardsley to Beaverbrook: Portraits by Walter Richard Sickert, exhibition catalogue, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath 1990 (4).

Arthur Symons, ‘The Primrose Dance: Tivoli – to Minnie Cunningham’, 20 March 1892; first published in Sketch, 4 October 1893; quoted ibid., p.19 n.30.

Walter Sickert, letter to Minnie Cunningham, 31 August 1897, private collection; quoted in Baron 2006, no.94.

Andrew McLaren Young et al, The Paintings of James McNeill Whistler, New Haven and London 1980, no.101.

Related biographies

Related essays

- Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke

- Empire and the City: Early Films of London Maurizio Cinquegrani

- Questions of Artistic Identity, Self-Fashioning and Social Referencing in the Work of the Camden Town Group Andrew Stephenson

- The Evolution of Painting Technique among Camden Town Group Artists Stephen Hackney

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

-

Walter Richard SickertDrawing

Related audio

-

Florrie Forde 1875–1940 performs 'Oh! The Fancy Petticoat' recorded September 1904© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

-

Marie Lloyd 1870–1922 performs 'A Little Bit of what you Fancy does you Good' recorded c.May 1915© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

-

Marie Lloyd 1870–1922 performs 'The Coster Girl in Paris' recorded July 1912© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Minnie Cunningham 1892 by Walter Richard Sickert’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www