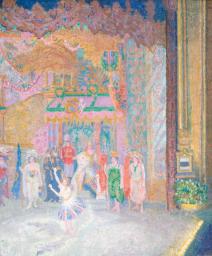

Spencer Gore Inez and Taki 1910

Spencer Gore,

Inez and Taki

1910

Visits to London’s music halls provided subject and inspiration for many of Gore’s paintings. He frequently haunted the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties in Leicester Square, the setting of this picture. Here Inez and Taki, possibly a Spanish double act, play nineteenth-century lyre guitars at stage right.

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Inez and Taki

1910

Oil paint on canvas

405 x 510 mm

Inscribed studio stamp ‘S.F. GORE’ bottom left

Purchased (Knapping Fund) 1948

N05859

1910

Oil paint on canvas

405 x 510 mm

Inscribed studio stamp ‘S.F. GORE’ bottom left

Purchased (Knapping Fund) 1948

N05859

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist in 1910 for £10 by Sir Louis Fergusson (1878–1962), from whose collection bought at Leicester Galleries, London, by Tate Gallery 1948.

Exhibition history

1910

The London Salon of the Allied Artists’ Association Ltd., 1910: Third Year, Royal Albert Hall, London, July 1910 (714).

1928

London Group Retrospective, New Burlington Galleries, London, April–May 1928 (82).

1936–7

Empire Exhibition, Johannesburg Art Gallery, September 1936–January 1937 (439).

1948

The Collection of Sir Louis Fergusson, K.C.V.O., Leicester Galleries, London, September 1948 (43).

2008

Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, Tate Britain, London, February–May 2008 (17, reproduced).

References

1930

Louis Fergusson, ‘Souvenir of Camden Town: A Commemorative Exhibition’, Studio, vol.99, February 1930, reproduced p.111.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, pp.247–8.

1952

John Rothenstein, Modern English Painters: Sickert to Smith, London 1952, p.200.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.240, 374.

1980

Simon Watney, English Post-Impressionism, London 1980, pp.56, 61, reproduced fig.38a.

1980

Wendy Baron and Malcolm Cormack, The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven 1980, p.41.

1986

Claudio Zambianchi, ‘Appunti su Spencer Frederick Gore e la pittura inglese fra il 1908 e il 1910’, Storia dell’Arte, no.58, 1986, reproduced fig.4.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.181.

Technique and condition

Inez and Taki is painted in artists’ oil paints on primed stretched canvas. The cloth was cut generously and several centimetres overlap the reverse of the stretcher. The top edge is a selvedge with black thread woven in. The back of the canvas is marked by the stamp of the artists’ colourman P. Shea of ‘56 Fitzroy Street, Tot.[tenham] Court Rd, London W’. The stamp is positioned just off-centre and the dimensions of the support conform to a size that was commercially available, suggesting that it was supplied pre-stretched. Two of Walter Sickert’s canvases in the Tate collection, dating from around the same period, are also marked with this stamp (Tate N05088 and N05430). The qualities of the cloth are similar but the preparation is quite different, suggesting perhaps that the artists wanted different qualities to their preparatory surface and a range of different preparations were commercially available at the time. Gore’s painting has a very thin glue-size layer which covers the canvas threads and is overlaid with dense white priming composed of fairly pure lead white. The primer appears to have penetrated the threads to an unusual degree, suggesting perhaps that they were roughened before the priming was applied. The resulting preparatory surface retains the rough texture of the canvas and is slightly absorbent.

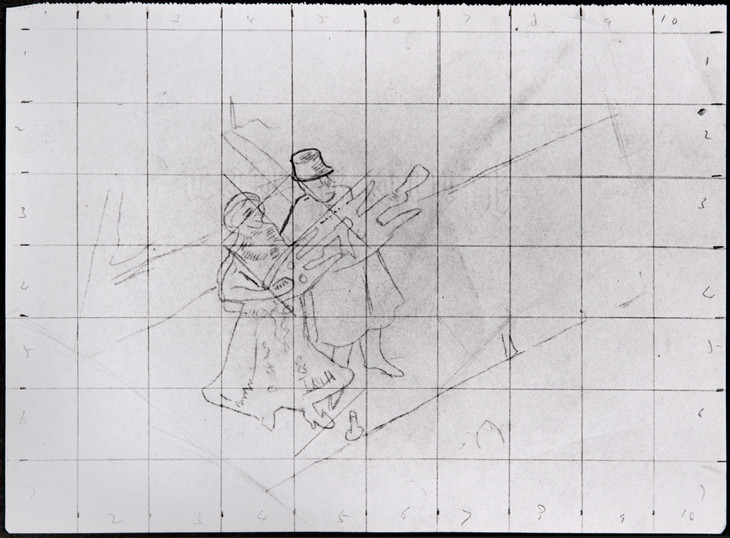

There are pencil marks at approximately two inch intervals around the edges of the stretched canvas which are traces of the method of squaring-up used to transfer the design from a compositional drawing. There is no visible trace of underdrawing in graphic media beneath the paint film; the compositional design is drawn in blue paint onto the primed canvas (see also Tate T02260). Forms are developed with broken colour deftly applied in dabs and light strokes of paint that retain the texture of the brush and reveal that of the canvas. This is most noticeable in Gore’s handling of the scenic backdrop, where paint is just lodged on the tops of the canvas weave. The flecked melange of closely toned but contrasting colours with small spots of the white priming exposed between touches creates a sense of intense illumination. The animated figures of the performers are more densely built up of closely manipulated paint which subtly distinguishes them from their setting. Darker but variegated colour is applied in the same dabs and light strokes in the shadows but leaving little of the white priming exposed. The darkest colours appear slightly greyer owing to efflorescence (phenomena observed on the surface of paintings as hazy, whitish, often obscuring patches, also described as blanching, chalking, etc.), probably resulting from the slightly under-bound paint film that is unvarnished.

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan

May 2005

How to cite

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', May 2005, in Robert Upstone, ‘Inez and Taki 1910 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Pre-dating any contact with Walter Sickert, Gore was passionately interested in the potential of subjects he observed in the theatre, ballet and music hall. This interest was longstanding, and he had himself performed in many amateur theatricals. His son Frederick Gore has written that:

Gore, whose great uncles had founded the Old Stagers together with the I Zingari – strolling cricketers and players – belonged to a family and circle of related families in which during at least five generations everyone had been expected to sing or dance and act. Whether his cousins wished to raise money for university extension lectures at Market Drayton, the Boys Brigade at Keswick, or soldiers’ and sailors’ orphans at Gravesend, Gore’s talent was much in demand as comic policeman, Victorian father or singer of character songs ... ‘The grouping of six Eastern ladies’, said the press cutting from Keswick in 1900, ‘in the character song by Mr Gore (who is evidently an accomplished actor) presented a very pretty effect and was loudly applauded’.1

The Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, Leicester Square, London c.1906

Colour-tint postcard

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.1

The Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, Leicester Square, London c.1906

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

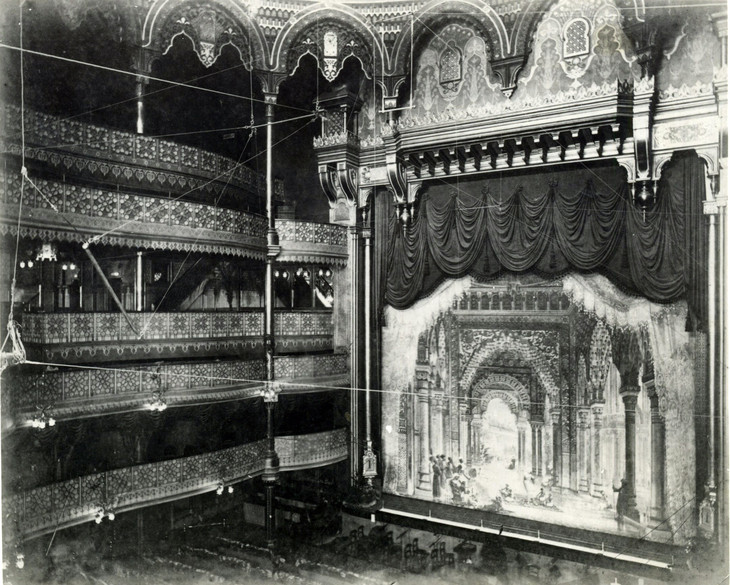

Gore wrote to his student John Doman Turner, ‘I go to the Alhambra nearly always on Mondays and Tuesdays 2/6 seats’.2 He also went to shows at the Empire Theatre, Leicester Square, and the New Bedford Music Hall on Camden High Street (see Tate T02260). On his visits to the Alhambra, Gore would make studies in his sketchbook of both the acts and the audience, and frequently both together. The backs of the audience’s heads, or the orchestra in the pit, often form an essential part of such observations, and this practice was evidently derived from Edgar Degas’s theatre pictures. Gore would, for instance, no doubt have been familiar with Degas’s Ballet Scene from Meyerbeer’s Opera ‘Roberto il Diavolo’,3 where the dancers are seen beyond a foreground of musicians, whose bassoons cut across our view of the stage. This was acquired as part of the Constantine Ionides Collection by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1901, although Gore would have been able to see it as early as 1898 when it was exhibited at the Guildhall Art Gallery, and it was also reproduced in both the Art Journal and the Burlington Magazine in 1904.4 That Gore saw it seems confirmed by the close compositional similarity of his Stage Sunrise, The Alhambra 1908–9 (private collection).5

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897

Photographic print

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.2

The Interior of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, London 1897

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

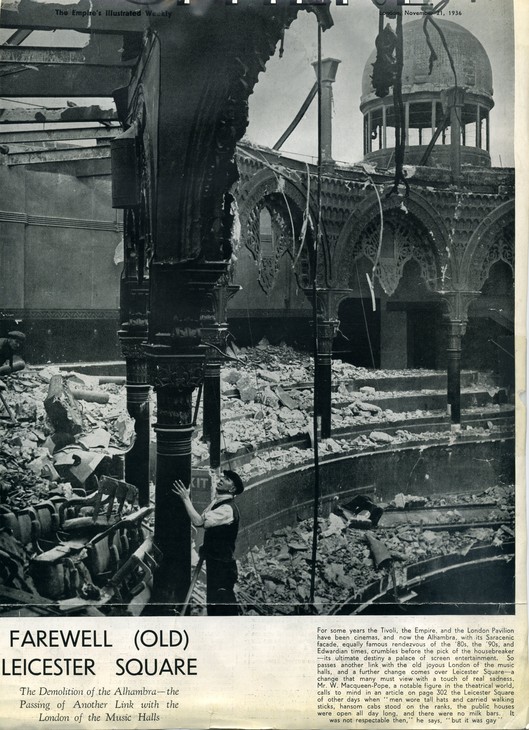

Demolition of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties 21 November 1936 From The Sphere

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

Fig.3

Demolition of the Alhambra Theatre of Varieties 21 November 1936 From The Sphere

The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection

Photo © The Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection / ArenaPal

From the continuity of his sketches and oils it is clear that Gore preferred to occupy the same seat on each visit. Indeed, this was essentially a necessity. To capture the often transient poses of the figures on the stage sometimes required several return visits to complete a sketch, and therefore to ensure continuity it was crucial he sat in the same seat. In his obituary of Gore, Sickert drew attention to this, noting, ‘I shall always remember my envy at the dogged way in which he would take his stand, with the regularity of clockwork, in all weathers, in the queue at the door of the Alhambra at an impossibly early hour so that he might find himself in the desired seat to continue his study of some chosen scene’.6 A tightrope walker required a whole series of visits. ‘Every time she got to a certain spot,’ Gore wrote to Doman Turner, ‘I had my pencil on the spot where I left off and added a little. It took some time.’7 Elsewhere, advising Doman Turner on his own attempts to make drawings in music halls, Gore wrote:

If you are going only one evening at a time, draw as quickly as you can and leave. Or draw only the head or hands or legs with the bit of scenery it comes against. It is very difficult to get very much out of a whole figure in one night.8

From his carefully observed studies Gore would select subjects for oil paintings. The potential of the colour and movement of the stage fascinated him, and also its strangeness. Gore frequently chose to depict music-hall acts which were exotic or slightly bizarre, such as one of the first of his theatre oils, The Masked Ball of 1903 (private collection),9 which shows a figure with a giant false head alongside a tower of acrobats in Martinetti’s Duel in the Snow. By contrast Sickert, in whose company Gore sometimes went to the music halls, had generally preferred to show the more celebrated performers of the day. Gore was particularly well known for his theatrical scenes, and in his obituary of him in Blast Wyndham Lewis, as Sickert had done in his own tribute, drew particular attention to them, writing, ‘The years he spent working on scenes from the London music-halls brought to the light a new world of witty illusion. I much prefer Gore’s paintings of the theatre to Degas’. Gore gets everything that Degas with his hard and rather paltry science apparently did not see.’10

Inez and Taki were one of the acts Gore saw at the Alhambra. Sir Louis Fergusson, the first owner of Gore’s picture, recalled in a letter to the Tate Gallery in October 1960: ‘I don’t think that Inez and Taki had a particularly long vogue in the Halls. They changed their name on the programmes to “The Takiness”. I don’t know their nationality.’11 Gore shows Inez and Taki playing lyre guitars,12 instruments that had been relatively common in the early nineteenth century but by this time would have appeared an extremely unusual and undoubtedly comic or eccentric choice. The name ‘Inez’ is the Spanish form of ‘Agnes’, which might suggest that the female performer perhaps originated from Spain; this possibility is supported by a report in the Times in 1912 that at ‘the Hippodrome this week come The Takiness and Faica and Flamenca, who will dance Spanish dances of an unusual character’.13 Reviewing the February programme at the Hippodrome, the Times noted ‘the whole programme is good ... including as it does ... Takiness with his extraordinary voice’.14 Indeed, his voice seems to have aroused considerable comment. The Times reported in July 1911 that ‘the male has a bass voice of abnormal depth, which is quite a curiosity’,15 and in August that year, reviewing the act’s performance at the Hippodrome, that:

The Takiness are certainly novel. The voice of His Takiness, while resembling that of a bull of Bashan, possesses all the depth and timbre of a gigantic bumble-bee. He never condescended to utter an intelligible sound, but his bell-like notes pierced the heart of Her Takiness, who was a charming contrast to her booming partner.16

Composition

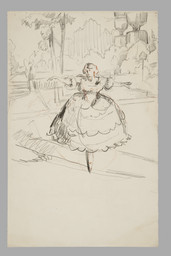

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Study for 'Inez and Taki' c.1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Fig.4

Spencer Gore

Study for 'Inez and Taki' c.1910

Private collection

Courtesy of the Gore family

Gore shows the duo from his position on the balcony above the orchestra pit, a viewpoint which leads to an unusual and visually dynamic arrangement of the composition. The diagonal lines of the stage front and the edge of the balcony intersect at the bottom left of the canvas, splitting the design into three distinct parts, while contrasts of colour and lighting serve to further emphasise this division of the composition. Gore used similar obliquely angled perspectives in a number of his other music-hall pictures, notably Ballet Scene from ‘On the Sands’ 1910 (fig.5) and The Balcony at the Alhambra 1911 (fig.6). Gore’s allowance of the edge of the balcony to intrude into the picture space and his inclusion of the orchestra in the scene make clear that this is a picture of a theatre at work rather than simply a portrait of the performers themselves. These visual intrusions are hallmarks of Degas’s theatre pictures, taken up by Sickert in the 1880s; but the originality of the high, oblique standpoint is distinctly Gore’s own. The critic Frank Rutter drew attention to the device in his enthusiastic review in the Sunday Times of Gore’s solo exhibition at the Chenil Galleries in 1911, and also made comparison with Degas:

That great painter Degas made the ballet and the dancers therein so peculiarly his own property that it has become a dangerous subject for any lesser painter to attempt. Louis Legrand has won some temporary success by reflecting Degas through his more commonplace temperament, but with all his cleverness he has not succeeded in conveying to us any new message. Mr. S.F. Gore, in his visions of the Alhambra stage, is as much as himself and as little reminiscent of any other painter as he is in his figures and still-lifes. The ballet affords him opportunities of colour which he interprets in his own way, the way of a colourist rather than the way of a draughtsman. This is not to disparage Mr. Gore’s draughtsmanship, for his nude studies must convince the dullest how fine is his sense of form, but it is a clumsy way of emphasising the absolute distinction between his point of view and that of Degas ... Mr. Gore has found at the Alhambra cunning patterns of arrangement as well as glowing harmonies of colour. Admirably hung ... his ballet scene ‘On the Heath’ (4) introduces with the happiest effect the curve of the balcony as an important element in this bird’s eye design, and the spectator, looking down on this most original composition, renews within himself the emotion of unexpected pleasure which the artist must himself have experienced when he first leant over the gallery and got caught in the swirl of an unforeseen rhythm ... The collection as a whole is a song of colour, the lyrical utterance in pure, clean pigment of a refined, sensitive and naively observant personality.19

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Ballet Scene from 'On the Sands' 1910

Oil paint on canvas

406 x 508 mm

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund

Fig.5

Spencer Gore

Ballet Scene from 'On the Sands' 1910

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

The Balcony at the Alhambra c.1911–12

Oil on canvas

485 x 355 mm

York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery) YORAG: 1384. Purchased with the aid of grants from the Museums and Galleries Commission / Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund, The National Heritage Museum Fund and the Friends of the York Art Gallery, 1983

Photo © York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)

Fig.6

Spencer Gore

The Balcony at the Alhambra c.1911–12

York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery) YORAG: 1384. Purchased with the aid of grants from the Museums and Galleries Commission / Victoria and Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund, The National Heritage Museum Fund and the Friends of the York Art Gallery, 1983

Photo © York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)

Ownership

In his letter to the Tate Gallery of October 1960, Sir Louis Fergusson described how he had been a friend of Gore, his exact contemporary, when they were at Harrow School. But they ‘drifted apart until we met by chance in the Café de l’Empire Leicester Square in about 1908 – a meeting which led to great friendship with other Camden Towners Gilman, Ginner and Bevan’.20 Fergusson became a strong supporter and patron of the Camden Town Group, and amassed an important collection of early modern British pictures which was exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in London in September 1948. He was Private Secretary to successive Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster (1909–21) and later Clerk of the Council of the Duchy of Lancaster (1927–45). A scrupulous diarist, elsewhere in his letter to the Tate, Fergusson described how he came to own Inez and Taki:

It was actually the first painting that I acquired. My diary reminds me that on the night of November 7th 1910 I met Gore by appointment at 19 Fitzroy St and purchased Inez and Taki for £10. We brought it back in a taxi to my small flat in Clement’s Inn, Gore hung it for me, and then we dined at Gow’s, took coffee at Rule’s and then returned to Clement’s Inn for an ‘artistic jaw’.21

The picture evidently appealed to Fergusson because of his own enthusiasm for the music hall. His obituary in the Times stated:

The old music-hall was another of his early and abiding delights. From his own experiences and the mass of material he had collected he privately printed in 1949 a short book, Old Time Music Hall Comedians, where he recalled in some detail with many quotations, the songs and personalities of famous stars, especially of the eighties and nineties.22

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Frederick Gore, ‘Spencer Gore: A Memoir by his Son’, in Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1974, pp.6–7.

Reproduced in Basil S. Long, Catalogue of the Constantine Alexander Ionides Collection, vol.1, London 1925, pl.11.

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (64).

Walter Sickert, ‘A Perfect Modern’, New Age, 9 April 1914, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.355.

Reproduced in Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1983 (1).

Related biographies

Related essays

- Leisure Interiors in the Work of the Camden Town Group Jonathan Black, Fiona Fisher and Penny Sparke

- Empire and the City: Early Films of London Maurizio Cinquegrani

- Questions of Artistic Identity, Self-Fashioning and Social Referencing in the Work of the Camden Town Group Andrew Stephenson

Related catalogue entries

Related archive items

Related reviews and articles

- Wyndham Lewis, ‘Frederick Spencer Gore’ BLAST, No.1, June 1914, p.150.

- Walter Richard Sickert, ‘A Perfect Modern’ The New Age, 9 April 1914, p.718.

Related audio

-

Violet Loraine (1886–1956) and George Robey (1869–1954) perform 'If you were the only Girl in the World' recorded c.April 1916© Windyridge Music Hall CDs

Related film

-

Performers at a theatrical garden party, including the comedians George Grossmith and Bobby Hales c.1910© British Pathé

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘Inez and Taki 1910 by Spencer Gore’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www