Harold Gilman 1876–1919

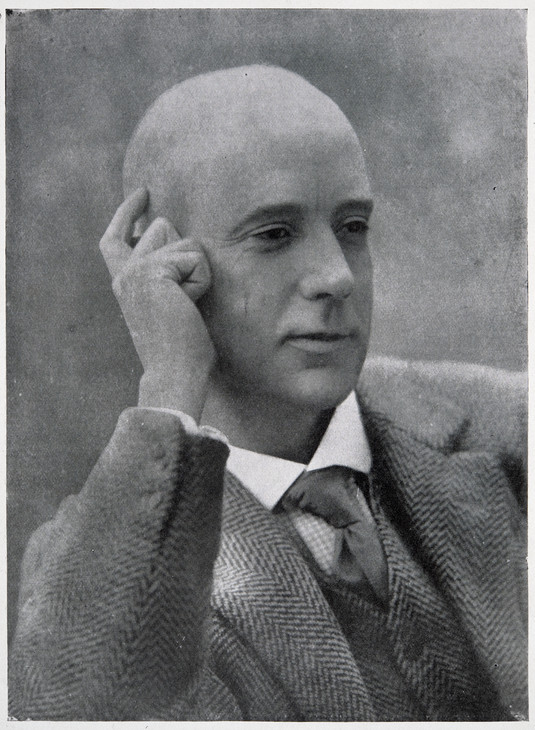

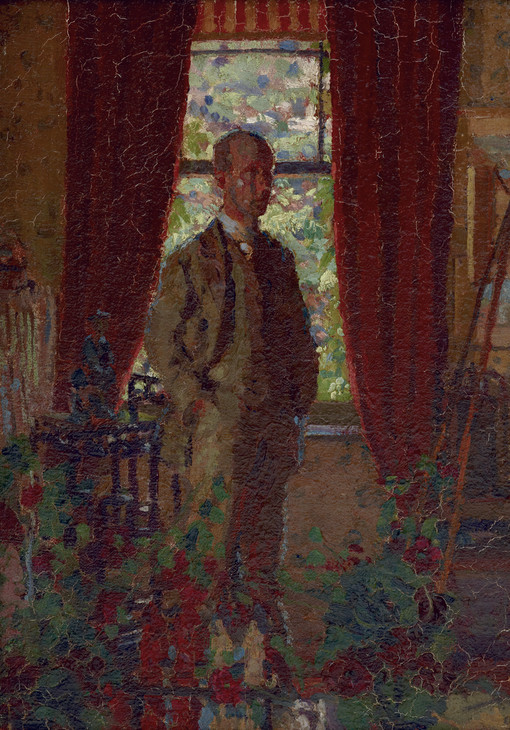

Harold Gilman was one of the main instigators in the formation of the Camden Town Group (figs.1 and 2). As the art critic Frank Rutter later recalled, Gilman was ‘an incorruptible puritan, who would have no half-measures, no bargaining, but stood solid for root-and-branch reform’ and so ‘consistently advocated the formation of a new society’.1 Despite dying at the age of forty-three in 1919, his strong-minded and ardent personality, as revealingly displayed in Walter Sickert’s portrait of c.1912 (Tate T00164, fig.3), meant that he made a lasting impact on the British art world at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Harold John Wilde Gilman was born on 11 February 1876 at Rode in Somerset. He was the second of seven children of the curate of Rode, John Gilman (1840–1917), and Emily Purcell Gulliver (1850–1940). In 1890 Gilman began boarding at Tonbridge School, north of Royal Tunbridge Wells in Kent, after his father secured the living of the villages of Snargate with Snave in Romney Marsh, near the south-east coast (fig.4). It was at Tonbridge School that Gilman badly injured his hip in 1891, leaving him incapacitated for nearly three years, during which time he discovered his love of art.2

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Self-Portrait c.1908–9

Oil paint on canvas

357 x 257 mm

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Purchased 1946

Fig.2

Harold Gilman

Self-Portrait c.1908–9

Art Gallery of New South Wales. Purchased 1946

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Harold Gilman c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 457 mm; frame: 795 x 652 x 100 mm

Tate T00164

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1957

© Tate

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

Harold Gilman c.1912

Tate T00164

© Tate

After attending Oxford University for just a year in 1894–5, Gilman left either owing to ill-health or because he decided to tutor the children of an English family in Odessa, where he stayed for about a year.3 In 1896 he enrolled at Hastings School of Art in Sussex, and from 1897 to 1901 he attended the Slade School of Fine Art. His contemporaries there were Spencer Gore, Albert Rutherston, Wyndham Lewis, Augustus John and William Orpen, and he was taught by Frederick Brown, Philip Wilson Steer and Henry Tonks.

Early style and inspiration

After leaving the Slade, Gilman spent over a year in Spain, much of the time copying the work of the great Spanish masters Diego Velázquez (1599–1660) and Francisco Goya (1746–1828) in the Prado in Madrid. Gilman later wrote an article in 1910 on ‘The Venus of Velasquez’, in which he repudiated claims that The Rokeby Venus in the National Gallery was not by the artist.4 Velázquez was of great importance to many of Gilman’s Slade contemporaries. This was partly due to the publication of an important monograph on the Spanish artist by R.A.M. Stevenson in 1895, where Stevenson described him as ‘the prophet of the new schools’ and saw him as the forerunner of impressionism.5 Stevenson sought to legitimise the work of English impressionist artists, such as the London-based American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler, by drawing parallels with what he called Velázquez’s ‘truth of impressionism’.6 Whistler’s smooth tonal handling was also of great importance to Gilman in the development of his style at this time.

Gilman was in Madrid at the same time as Gore and Lewis, although it is not known whether they saw each another. It was there too that he met his first wife, Grace Cornelia Canedy (c.1864–c.1957), who was the daughter of a wealthy Chicago industrialist and was also there to copy Velázquez. On 2 February 1902 they married in the garden of the United States consulate in Toledo.7

The couple returned to England towards the end of 1902 and on 19 January 1904 their first daughter Elizabeth was born at 128a Lancaster Road, Notting Hill.8 Gilman showed at the spring exhibition of the New English Art Club that year, where his address is given as The Rest, The Moors, Pangbourne, Berkshire,9 indicating that the family had already decided to move out to the countryside. Later on in the year Gilman was in Ottawa working on some murals, now lost, for a Canadian government building, before joining Grace in Chicago where their second daughter Hannah was born on 4 February 1905. Grace’s father reputedly tried to persuade Gilman to join his business, but the artist refused.10

In February 1907 Gilman and Sickert were introduced. Shortly afterwards saw the formation of the Fitzroy Street Group, of which Gilman was a founder-member. Gilman’s friend Louis Fergusson recalled that at this time he was

a figure of dignity in snuff-coloured suit and black neckerchief. He impressed you with his transparent earnestness. Painting meant ever so much to him. He told you with the utmost conviction that Freddie Gore was going to be a very great painter, that the next important art-movement would certainly emanate from the room in which we were standing.11

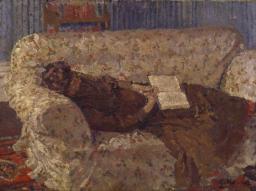

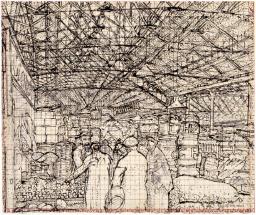

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

In Sickert’s House at Neuville 1907

Oil paint on canvas

587 x 457 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.5

Harold Gilman

In Sickert’s House at Neuville 1907

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

were very intimate – very smoothly painted – without impasto – without excrescences. Degas, who disliked anything growing out of a canvas – any thrust of pigment into the third dimension – would have passed his hand over the surface with entire satisfaction. The attitudes of the people represented at their domestic avocations were gravely rendered in an illumination both subtle and subdued; the tones harmonized with impeccable taste.12

Gilman and his family stayed in Sickert’s house at Neuville outside Dieppe from the summer of 1907 (fig.5).14 In March 1908 he exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris for the first time, showing there again in 1909, 1910, 1912 and 1913.15 Back in England he was part of the group that helped Rutter to form the Allied Artists’ Association, which was inspired by the non-jury Salon. He showed at the first exhibition in July 1908 at the Royal Albert Hall. It was at the AAA in 1910 that Gilman and Gore met Charles Ginner – that year all three were on the Hanging Committee owing to their surnames beginning with the letter ‘G’.16

Post-impressionist influence

On 20 September 1908, Gilman’s son David was born at Letchworth Garden City in Hertfordshire. The family address at this time was 15 Westholm Green, Letchworth,17 close to the designer William Ratcliffe who lived at number 10, whom Gilman befriended. As the art historian Wendy Baron observes, ‘It tells much of the power of Gilman’s personality that he persuaded Ratcliffe, at the age of fifty, to take up painting again by studying part-time at the Slade in 1910 and by spending his Saturday afternoons in the Fitzroy Street Group studio.’18

Harold Gilman's house, 100 Wilbury Road, Letchworth Garden City

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Fig.6

Harold Gilman's house, 100 Wilbury Road, Letchworth Garden City

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Hampstead Road B.D.V. c.1910–11

Oil paint on canvas

254 x 305 mm

Private collection

Photo © The Fine Art Society, London / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.7

Harold Gilman

Hampstead Road B.D.V. c.1910–11

Private collection

Photo © The Fine Art Society, London / The Bridgeman Art Library

Gilman commissioned a larger family home to be built at 100 Wilbury Road (fig.6), but less than a year later Grace left for Chicago with their three children and did not return, perhaps owing to irreconcilable differences and pressure from her family.19 Following their separation, Gilman spent more time in London (fig.7) and became increasingly outspoken at 19 Fitzroy Street.20 Rutter wrote that after his marriage break-up:

Roughly handled by life, Gilman began to think for himself and take little or nothing on trust. In politics he became a Socialist with a profound dread and distrust of Society; while in art his loyalty to a ‘safe’ painter like Velazquez began to be undermined by a growing interest in the work of such ‘rebels’ as Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh.21

As a result of these growing interests, Gilman began to use brighter colours and thicker paint – a new style epitomised in The Blue Blouse: Portrait of Elèni Zompolides c.1910 (Leeds City Art Gallery).22 More than any of the other Fitzroy Street members, who were already familiar with modern continental work, Gilman was especially inspired by Roger Fry’s exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists at the Grafton Galleries from October 1910. A trip he took to Paris around this time with Rutter and Ginner where they saw modern paintings in the Pellerin and Durand-Ruel collections and at the Vollard and Sagot galleries also stimulated a new direction in Gilman’s art.23

According to Rutter, the ‘immediate sequel of this visit [to Paris] was Gilman’s production of a series of admirable “dot” drawings in emulation of those of Van Gogh’.24 Rutter felt that ‘Van Gogh particularly appealed to him, partly because Gilman himself had in him a good deal of the Dutchman’s fanatical humanitarianism, partly because he was fascinated by van Gogh’s technique, and partly because van Gogh was the special idol of his friend, Charles Ginner’.25 As the artist Wyndham Lewis described, van Gogh was in fact so important to Gilman that:

If you went into his room, you would find Van Gogh’s Letters on his table: you would see post cards of Van Gogh’s paintings beside the favourites of his own hand. When he felt very pleased with a painting he had done latterly, he would hang it up in the neighbourhood of a photograph of a painting by Van Gogh.26

The allegiance to van Gogh was something that stayed with Gilman throughout his life.

The Camden Town Group and ‘Neo-Realism’

Gilman’s conviction that, as Walter Bayes remembered, ‘nobody really counted as a painter who was outside his own group’,27 led to his perseverance with the formation of the Camden Town Group. Ginner wrote that Gilman was the ‘prime mover’ in the formation of the group because the New English Art Club had been rejecting his and his friends’ works, so that ‘Something had to be done, and when possessed with the idea that some wrong needed redressing he was not one to let the matter rest until something had been done’.28 Rutter recalled that not everyone was keen on breaking away from the NEAC, but ‘Gilman was tooth-and-nail against any compromise with the enemy, and was definitely in favour of founding a new exhibition body’, so that ‘Eventually the persistence of Gilman triumphed’ and the Camden Town Group was formed.29

Gilman exhibited at all three of the Camden Town Group exhibitions, and also held joint exhibitions with Gore in 1913 and Ginner in 1914.30 By the time of Gilman and Ginner’s exhibition in April, they had already announced themselves as ‘Neo-Realists’ in an article Ginner wrote for the New Age in January of that year and in the Allied Artists’ Association exhibition in July the previous year. Gilman had always been a keen realist, as his statement of 1910 attests:

No flower is better placed than where it grows, or in a vase by one not thinking of expression. The teacup filled shows best the thought that filled it; when it is emptied another pattern on the table will be formed. Life dictates the shapes. The artist only holds them. If forms don’t please, look for another motive. Nothing but life can imitate the real. The natural inclination of a head or its aversion shows the intention and the subtlest thought. This is composition.31

In ‘Neo-Realism’, Ginner stated that:

Greco, Rembrandt, Millet, Courbet, Cézanne – all the great painters of the world have known that great art can only be created out of continued intercourse with nature.32

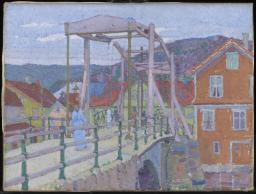

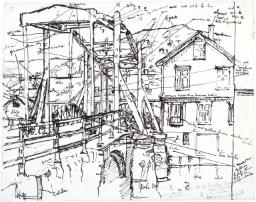

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

In Gloucestershire 1916

Oil paint on canvas

597 x 463 mm

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.8

Harold Gilman

In Gloucestershire 1916

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Gilman’s new alliance with Ginner signalled his eventual breach with Sickert. Lewis described the rift comically:

After his break of what was more or less discipleship with Walter Sickert and his plunge into the Signac palette and a brighter scheme of things ... He would look over in the direction of Sickert’s studio, and a slight shudder would convulse him as he thought of the little brown worm of paint that was possibly, even at that moment, wriggling out onto the palette that held no golden chromes, emerald greens, vermilions, only, as it, of course, should do. Sickert’s commerce with these condemned browns was as compromising as intercourse with a proscribed vagrant.36

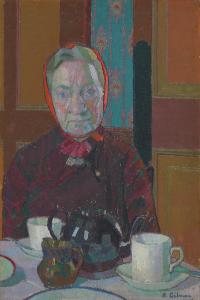

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 406 mm; frame: 808 x 605 x 93 mm

Tate N05317

Purchased 1942

Fig.9

Harold Gilman

Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table exhibited 1917

Tate N05317

Sickert reinforced the divide between himself and his former Camden Town Group colleagues when, in response to Ginner’s ‘Neo-Realism’ article, he mischievously labelled Gilman and Ginner as ‘The Thickest Painters in London’.37 Gilman was also hurt and put in financial difficulty when in 1915 Sickert took back a teaching post at the Westminster School of Art that Gilman had assumed after Gore’s death.38

Gilman and Ginner formed their own exhibiting society, the Cumberland Market Group, with Robert Bevan amongst others (figs.10 and 11), which showed only once at the Goupil Gallery in 1915.39 After Gilman lost his post at Westminster, he and Ginner set up their own art school at 15–16 Little Pulteney Street in Soho in January 1916 where they would deliver their own particular views on art. As their student Marjorie Lilly recalled:

On one side of the room was a reproduction of Toulouse Lautrec’s picture ‘A la Mie’ and on the other wall a print of the famous Van Gogh self portrait with pipe in mouth and bandaged ear. Before he began to paint, Gilman would wave his brush in the air and bow towards the portrait, crying, ‘A toi, Van Gogh!’ ... Everyone followed in the steps of the master and I found this orgy of rainbow hues confusing ... As for spreading the thick paint, of the consistency of clay, on the canvas, I soon decided that Sickert was right; it was like walking across a ploughed field in pumps. Although we were not encouraged to use any medium I longed to smuggle in a little turpentine when no one was looking to thin this stiff mixture.40

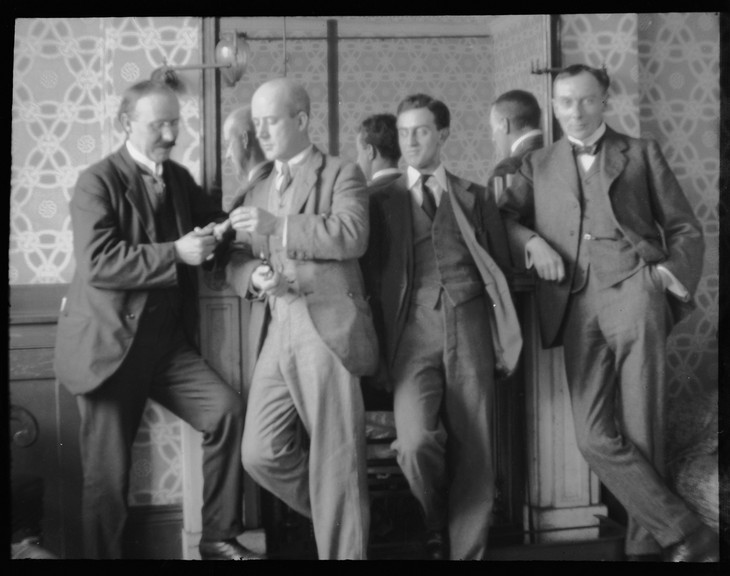

Alvin Langdon Coburn 1882–1966

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, John Nash, Robert Bevan and Harold Gilman

Negative, gelatine on nitrocellulose roll film

90 x 120 mm

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Fig.10

Alvin Langdon Coburn

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, John Nash, Robert Bevan and Harold Gilman

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Alvin Langdon Coburn 1882–1966

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, Harold Gilman, John Nash and Robert Bevan

Negative, gelatine on nitrocellulose roll film

90 x 120 mm

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

Fig.11

Alvin Langdon Coburn

The Cumberland Market Group c.1915 from left to right: Charles Ginner, Harold Gilman, John Nash and Robert Bevan

Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

© Estate of Alvin Langdon Coburn

For health reasons, Gilman did not serve in the war. However, he was commissioned by a committee in London headed by Lord Beaverbrook to paint Halifax Harbour in Nova Scotia in 1918,43 which had been devastated in a massive munitions explosion late the previous year in which nearly two thousand people died and thousands more were injured or left homeless.44 As Wendy Baron notes, ‘he worked with unrelenting dedication, in all weathers’ to fulfil the commission,45 producing the largest work of his career, Halifax Harbour at Sunset 1918 (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa),46 which tells very little about the recent devastation, as the viewpoint is set back so that the harbour appears undisturbed.47 Lewis said of this:

If you are to seek for anything dramatic in his death, it is that his last picture (that of Halifax Harbour), on exhibition during his last illness, was in many ways the best he had done.48

Memorials

Gilman died on 12 February 1919 in the French Hospital on Shaftesbury Avenue, a victim of the postwar influenza epidemic, catching the illness from nursing his friend Ginner.49 Lewis and Fergusson were quick to publish Harold Gilman: An Appreciation in the summer. Fergusson regarded ‘His premature death ... a great misfortune for English independent art’,50 and Lewis said of his former Slade contemporary:

He had a great capacity for friendship, a poor and third-rate gift for hatred, every virtue of middle-class England, and, in fact, was one of the most amusing, genuine, equable, sensitive individuals I have met. And all his contemporaries agreed that he was a good painter.51

Rutter later wrote that Gilman died ‘just as he was entering on a last phase of supreme technical mastery and individual distinction’.52 That summer Ginner also wrote an article on his friend in Art and Letters, the journal they had set up with Frank Rutter, which was reproduced in the catalogue for Gilman’s memorial exhibition held in October 1919 at the Leicester Galleries. Ginner wrote that Gilman’s death, ‘coming so few years after that of Spencer F. Gore, is a great loss to the modern art movements in this country’, which ‘owe much to the efforts of ... Gilman, whose achievements in painting and whose keen interest in all attempts to bring artists together will long be remembered’.53

Notes

Wendy Baron, ‘Gilman, Harold John Wilde (1876–1919)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/37457 , accessed 4 February 2010.

Andrew Causey and Richard Thomson (eds.), Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981, p.37 and Baron 2004, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/37457 .

Louis Fergusson, ‘Souvenir of Camden Town: A Commemorative Exhibition’, Studio, February 1930, p.112.

Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Harold Gilman’, in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London 1919, pp.19–20.

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, no.7.

Frank Rutter, ‘The Work of Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore: A Definitive Survey’, Studio, vol.101, no.456, March 1931, p.207.

Wyndham Lewis, ‘Harold Gilman’, in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London 1919, pp.12–13.

Frank Rutter, ‘The Camden Town Group: A Fragment of History’, in The Camden Town Group: A Review, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1930, p.8.

Paintings by Spencer F. Gore & H. Gilman, Carfax Gallery, London, January 1913. An Exhibition of Paintings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1914.

Arts Council 1981, p.38. It was at Westminster that Gilman met his second wife in 1914, (Dorothy) Sylvia Hardy, formerly Meyer (1892–1971), who was a student at the school. After marrying in 1917 they lived briefly with Sylvia’s parents at Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, before moving to 53 Parliament Hill Fields, Hampstead.

An Exhibition of Works by Members of the Cumberland Market Group, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1915.

Willem A. Blom, National Gallery of Canada: Illustrated Guide to the Collections, Ottawa 1964, p.88, reproduced p.89.

James H. Marsh, ‘The Halifax Explosion’, The Canadian Encyclopedia, http://thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=ArchivedFeatures&Params=A295 , accessed 4 February 2010.

Catalogue entries

How to cite

Helena Bonett, ‘Harold Gilman 1876–1919’, artist biography, October 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www