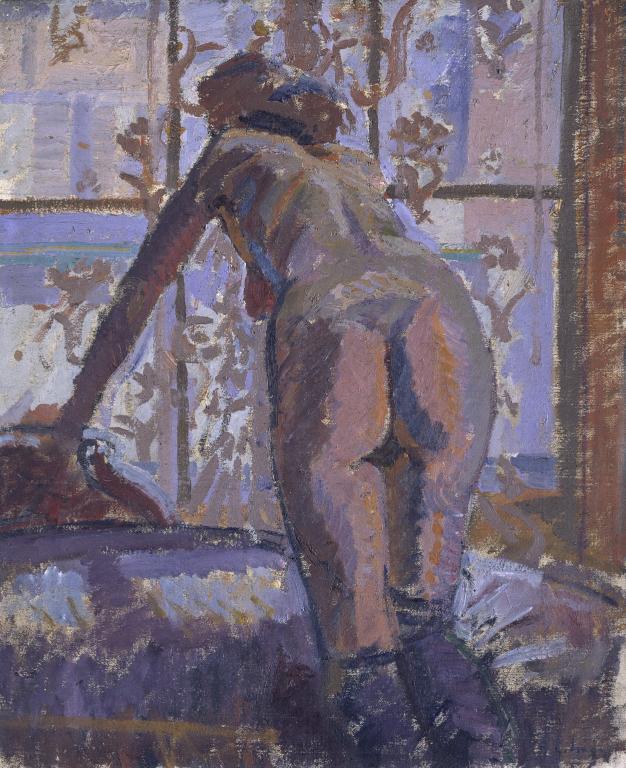

Harold Gilman Nude at a Window c.1912

Harold Gilman,

Nude at a Window

c.1912

Bent over towards a window, the model in this painting provocatively presents her naked body to the viewer. The spontaneous feel of her pose and Gilman’s loose brushwork in complementary purples and oranges gives the work an atmosphere of sexual freedom.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Nude at a Window

c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 508 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010

T13227

c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 508 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010

T13227

Ownership history

Acquired from the artist by Spencer Gore (1878–1914), ?from whom acquired by Robert Bevan (1865–1925); by descent to the artist’s son, Robert Alexander Bevan (1901–1974), and thence by descent to his wife Natalie (1909–2007); accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010.

Exhibition history

1913

?Paintings by Spencer F. Gore and Harold Gilman, Carfax Gallery, London, January 1913 (?39, as ‘Nude (No.4)’, 20 guineas).

1954–5

Harold Gilman 1876–1919, (Arts Council tour), Arts Council, London, January–December 1954, Manchester Art Gallery, November–December 1954, Tate Gallery, London, May–June 1955 (17, as ‘Nude Figure Against a Window’).

1967

The Camden Town Group & English Painting 1900–1930’s, William Ware Gallery, London, March 1967 (37, as ‘Nude at Window’).

1975

The R.A. Bevan Collection from Boxted House, The Minories, Colchester, July–August 1975 (70, as ‘Nude at Window’).

1979–80

Post-Impressionism: Cross-Currents in European Painting, Royal Academy, London, November 1979–March 1980 (295, as ‘Nude at Window’, reproduced).

2008–9

A Countryman in Town: Robert Bevan and the Cumberland Market Group, Southampton City Art Gallery, September–December 2008, Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, January–March 2009 (no number).

2008–10

From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, March–June 2008, Brighton Art Gallery and Museums, April–September 2010 (23, reproduced).

References

1913

‘Pictures. The Carfax Gallery’, Times, 24 January 1913, p.10.

1954

J. Wood Palmer, ‘Introduction’, in Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1954, p.4.

1977

Christopher Neve, ‘Pioneer Collection in a Vivid Setting: Camden Town Pictures at Boxted House’, Country Life, vol.161, no.4170, 2 June 1977, p.1506.

1981

Andrew Causey and Richard Thomson (eds.), Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981, nos.18, 25 and 27.

1992

Tate Report: Tate Gallery Biennial Report 1990–92, London 1992, p.92.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: The Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, no.19, reproduced p.125.

2008

Alice Strang, ‘Bobby and Natalie Bevan and the Art at Boxted House’, in From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2008, p.13.

2008

Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, London 2008, pp.87–8, reproduced p.87.

Technique and condition

Nude at a Window is painted in artists’ oil colours on a commercially prepared fine, plain-weave linen canvas that retains an original unprimed selvedge along the left side. The textile support consists of one piece. The priming has the appearance of an off-white ground applied evenly over the canvas sized with animal glue. It extends to the cut edges of the canvas and retains the canvas structure. The primed textile is attached onto its original four-member stretcher with tacks which appear to be the original fixing.

The initial sketch, which sets out the figure and the structure of the space, is done in dark blue oil paint and remains visible between brushstrokes of the upper layers. Blocks of oil colour have then been laid in with rapid, dry brushstrokes which are broken with glimpses of the luminous white of the ground. The artist has used opaque but medium-rich oil paint, which is stiff enough to retain the shape and definition of the brushstrokes. He uses the pattern and direction of the brushstrokes to enhance the three-dimensional form of the nude. Within the outline the artist has blocked in the flesh with flat areas of colour before employing strategically placed, directional brushstrokes in thicker, opaque colour.

The unvarnished paint is leanly bound and matt. There are areas of blanching, predominantly in blue or purple paint areas which wet out temporarily but reblanche when dry.

Annette King

September 2004

How to cite

Annette King, 'Technique and Condition', September 2004, in Helena Bonett, ‘Nude at a Window c.1912 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, November 2010, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Description

In this painting a female figure, seen from behind and wearing only stockings, leans towards a window supporting herself with her left arm and right knee on a piece of furniture. It is a casual pose: the figure seems to be trying to reach forward to catch a glimpse of something outside while dressing. It is also a picture of remarkably relaxed and frank sexual allure.

The light from the window creates a contre-jour effect with deep purple shadows down the figure’s left arm and side. A blue and mauve register has been used throughout, punctuated with complementary orange and yellow highlights. Semi-abstract patterns appear to float around the body; these undoubtedly indicate the design of a net curtain, but the gestural quality of their handling lends a dreamlike and private aspect to the scene.

The artist often worked slowly and methodically from squared-up drawings to create his paintings. In this case, however, he loosely sketched the scene directly onto the canvas using dark blue oil paint. The rest of the brushwork is freely handled with the ground showing through in many places, indicating that much of the painting might have been executed with the model in front of him.

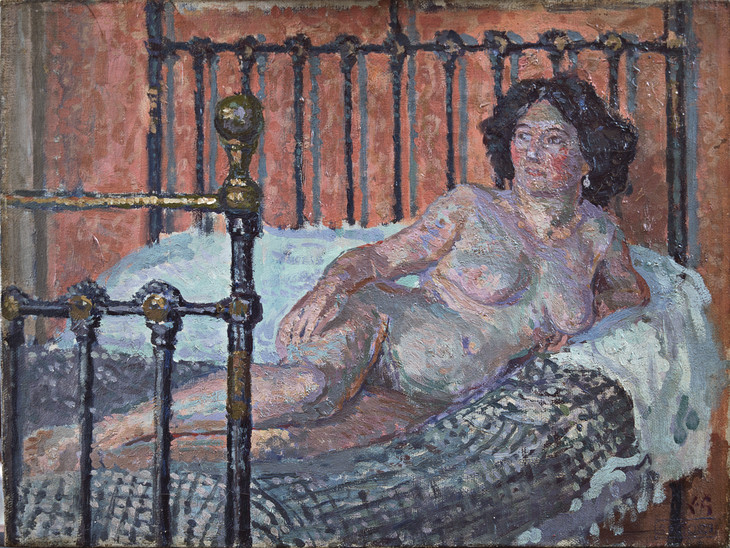

It is not known who the model is; she looks to be the same woman depicted in Nude on a Bed c.1911–12 (fig.1),1 while in their 1981 catalogue Andrew Causey and Richard Thomson note that the same setting and possibly the same model were used for Woman Combing her Hair c.1912 (Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter).2 She could be a professional model or possibly the person described by Ethel Sands as being Gilman’s ‘chère amie’ at this time, who also modelled for Walter Sickert; Sickert, likewise, remarked that Gilman kept a ‘superfluous’ woman after his marriage break-up in 1909.3 Although it cannot be known for certain who the model is, the impression given in this painting of the figure’s ease in her nakedness can be seen as suggesting that the scene is one of reciprocal sexual freedom. However, the work is also part of a series Gilman executed at this time that engage with the nude as a subject for modern painting.

The nude

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Nuit d'été c.1906

Oil on canvas

450 x 380 mm

Private collection, Ivor Braka Ltd

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ivor Braka Ltd, London

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Nuit d'été c.1906

Private collection, Ivor Braka Ltd

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Ivor Braka Ltd, London

Inspired by French impressionist artists such as Edgar Degas, Sickert broke with academic tradition in the early 1900s, painting nudes from unusual viewpoints,6 and in sexually explicit positions (fig.2). His La Hollandaise c.1906 (Tate T03548, fig.3) obscures the model’s features, allowing the viewer to focus simply on her body, in a manner similar to Gilman’s frank view of a woman from behind. Gilman’s friend Spencer Gore also explored the subject, presenting comparatively unidealised unclothed figures in domestic settings in such works as Nude 1910 (fig.4).

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

La Hollandaise c.1906

Oil paint on canvas

support: 511 x 406 mm; frame: 722 x 630 x 104 mm

Tate T03548

Purchased 1983

© Tate

Fig.3

Walter Richard Sickert

La Hollandaise c.1906

Tate T03548

© Tate

Spencer Gore 1878–1914

Nude 1910

Oil paint on canvas

515 x 610 mm

Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery

Fig.4

Spencer Gore

Nude 1910

Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery

Photo © Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery

The amount of critical attention given to Sickert’s paintings of nudes in the first Camden Town Group exhibition held in June 1911 may have inspired Gilman to take up the subject. Gilman exhibited two paintings of naked females at the group’s second exhibition in December that year, and went on to produce a series in 1911–13, including Nude 1911 (Mayor Gallery, London),7 Nude on a Bed 1911–12 (York City Art Gallery),8 Nude Seated on a Bed 1911–12 (Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester),9 The Model. Reclining Nude 1911–12 (Arts Council, London)10 and Nude on a Bed c.1911–12 (fig.1). He is not known to have returned to the subject after this period.

Diego Velázquez 1599–1660

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus') 1647–51

Oil paint on canvas

1225 x 1770 mm

National Gallery, London

Photo © National Gallery, London

Fig.5

Diego Velázquez

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus') 1647–51

National Gallery, London

Photo © National Gallery, London

In one of the few articles he ever published, Gilman contributed to the debate surrounding The Toilet of Venus by verifying that it was a work by Velázquez. He stated in the Art News in 1910:

In the controversy about the Venus of Velasquez perhaps I may be allowed to give evidence of identification. I am as one who has been hospitably entertained by a man, and has learnt to know his every attitude and characteristic so that I can recognize him at a distance with his back turned, or by the sound of his footsteps. For I spent more than a year almost constantly in the museum of the Prado, and made several copies.13

He goes on to confirm the authenticity of the work: ‘The red curtain, which I know as well as I know my own overcoat, figures in two or three of his other masterpieces.’14

Gilman’s sequence of nudes should, then, be viewed in the light of his enthusiasm for Velázquez.15 The Toilet of Venus and Nude at a Window share the defining feature of presenting a back view of a woman in an erotic, inviting and naturalistic way. A strong advocate of realism, Gilman stated in 1910: ‘Almost every picture painted, or at any rate hung on the walls of the galleries, is nothing but an impudent criticism of Nature.’16 The model in Gilman’s work is not a passive figure with gaze averted for the benefit of the viewer, but a real woman actively moving to look out of the window, gazing on to the street below or houses opposite.

Exhibition and reception

The reviews of Gilman’s two nudes at the second Camden Town Group exhibition in 1911 were mixed. The Daily Telegraph critic Sir Claude Phillips claimed:

‘Nude, No.1,’ is not only needlessly repellent but pictorially uninteresting, while ‘Nude, No.2’ – the same model with the same imperfections less cynically exhibited – is made attractive by a flicker of fitful sunlight on the undraped body that seems to crave indulgence from the spectator for its ugliness.17

The critic of the Queen found that ‘Mr H. Gilman shows perhaps more sympathy with colour than some of his companions, but his nude studies are not particularly pleasant’.18 It is unlikely that Nude at a Window was shown in this exhibition, as the Times critic stated that the depicted figures were seated:

Mr. H. Gilman, who shows the influence of Mr. Sickert, does not produce quite the same impression with his two very able nudes (20 and 22). They look as if they were sitting to be painted, not as if the artist had surprised them at some characteristic moment. You scarcely notice Mr. Sickert’s colour, it belongs so entirely to his subjects. But Mr. Gilman’s colour seems rather to be imposed upon his subjects, though it surprises with its freshness and ingenuity. His pictures are very well made, but they are made, whereas Mr. Sickert’s seem to have grown.19

However, fellow Camden Town Group member James Bolivar Manson writing in Outlook enjoyed Gilman’s work:

I admire Mr. Gilman’s robust, frank, courageous way of looking at life. He has an extraordinary power of seeing a thing as a whole, with a quite remarkable appreciation of all sorts of values. He has a profound knowledge of values of tone, colour, light, and interest, and consequently his pictures are finely lucid and have a rare quality of unity. Everything keeps its place, and there is no confliction of intentions. His brilliant expression is entirely through the medium of separation of tones. His pictures are virile pieces of life, not collections of objects, as in pictures painted after the Royal Academic recipe, where every detail is equally important, or rather unimportant.20

Gilman went on to exhibit more paintings of nudes in his joint show with Spencer Gore at the Carfax Gallery in January 1913. Analysing the layout sketch for this exhibition,21 the art historian Wendy Baron argues that Nude at a Window is Nude (No.4), as the plan ‘shows Nude (No.1) as a small painting, Nude (No.2) and Nude (No.3) as slightly larger, upright, paintings and Nude (No.4) as larger still and of pronounced vertical format. This last was inscribed on the plan “Back View” and priced at £20, whereas the other three were £15.’22 The only known back views are the Tate work and the Fitzwilliam’s Nude on a Bed (fig.1).

In a review of this exhibition, the critic of the Times exclusively focused on Gilman’s nudes:

Mr. Gilman remains an Impressionist who attempts the difficult task of seeing the nude with an Impressionist innocence of vision. By that we do not mean a moral innocence, for that is common to all good art, but the innocence which can see a nude figure as if it were merely an object in a landscape, which can forget its human interest in the play of light upon its delicate surfaces and in all the subtleties of colours that result from that play. Mr. Gilman paints, not the permanent facts of the human body, the facts which are learnt in a drawing school, but only those which are revealed at a particular moment and in particular circumstances of lighting. Or, rather, that is what he tries to do. For underneath all his precise and alert observation of those momentary facts we are still aware of a rather commonplace and even photographic drawing which is incongruous with the artist’s impressionism. The colour is always original in that it is a rendering of what he has actually seen, but the design is not equally original, for it is partly based upon what he knows to be there. The least photographic of his four nude studies is the first (7); but here he has painted the light on one side of the body as Segantini painted light upon a snowy peak, and the violence of the execution distracts our attention from what is represented, and indeed smothers all facts in a mess of paint. Still, this picture is charming and original in colour, and there is also much beauty of colour in all the other nudes. Mr. Gilman is still in the stage of eager curiosity; but an artist cannot discover the nature of his own talent without that.23

Ownership

Nude at a Window was first owned by Spencer Gore, who may have acquired it after his and Gilman’s joint exhibition in 1913. It is generally assumed to have then come into the possession of their fellow Camden Town Group member Robert Bevan.24 Walter Bayes wrote of Bevan:

Bevan was rather the Mæcenas of the group whose subscription was always paid to date, and he was, I fancy, sometimes a help in time of trouble. His gruff voice and appearance of a fox-hunting squire was rather refreshing at Fitzroy Street, where some (of the visitors rather than the members) tended to be ‘arty.’ When respectable American ladies who were seeing ‘Yurrup’ came to Fitzroy Street, it was Bevan who used to fish out for display to them Gilman’s most realistic and intimate nudes.25

Bevan’s son, Robert A. Bevan, displayed the work in the library, his private study, in Boxted House in Boxted, Essex.26

Helena Bonett

November 2010

Notes

Andrew Causey and Richard Thomson (eds.), Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981 (27).

Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1977, pp.99, 134. Equally, Causey and Thomson think that the lover might be the model in both Nude on a Bed 1911–12 (York City Art Gallery) and Nude Seated on a Bed 1911–12 (Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester), where the woman looks up at the viewer/artist. This model’s hairstyle and body indicate that she is not the same person as in Tate’s painting. See Arts Council 1981, p.53.

Reproduced at the Whitworth Art Gallery, University of Manchester, http://www.whitworth.manchester.ac.uk/collection/advsearch/objdisp/?irn=4623&QueryPage=%2Fcollection%2Fadvsearch%2Fresults%2F&QueryName=BasicQuery&QueryTerms=nude+on+a+bed&StartAt=1&QueryOption=all&all=SummaryData|AdmWebMetadata&Submit=Search , accessed 27 November 2010.

Interview in the Star, 22 February 1952. Quoted in Lynda Nead, The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality, London and New York 1992, p.37.

Of the Arts Council’s The Model. Reclining Nude, Andrew Causey and Richard Thomson note that although the figure ‘faces the spectator, her torso, head and arms are arranged in a similar fashion to Velasquez’s nude’. Arts Council 1981 (26).

Sir Claude Phillips, ‘Art Exhibitions. The Camden Town Group’, Daily Telegraph, 14 December 1911, p.16.

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: The Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, fig.5, p.57.

This possibly might not be accurate as it is listed as ‘Lent by Mrs M.[ollie] Gore’, Spencer Gore’s widow, to the 1954–5 Arts Council exhibition. In which case, Robert A. Bevan would have acquired it from Mollie after this date.

A photograph of the work hanging in the library is reproduced in From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, exhibition catalogue, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2008, fig.31, p.69. A photograph of the painting hanging in the drawing room is reproduced in Christopher Neve, ‘Pioneer Collection in a Vivid Setting: Camden Town Pictures at Boxted House’, Country Life, vol.161, no.4170, 2 June 1977, p.1505.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Harold Gilman, ‘The Venus of Velasquez’ The Art News, 28 April 1910, p.198.

- Author unknown, ‘The Carfax Gallery’ Queen, 9 December 1911.

- Sir Claude Phillips, ‘Art Exhibitions. The Camden Town Group’ The Daily Telegraph, 14 December 1911, p.16.

- James Bolivar Manson, ‘The Camden Town Group’ The Outlook, 9 December 1911, pp.823–4.

- Author unknown, ‘Picture Shows. The Camden Town Group’ The Times, 11 December 1911, p.12.

- Harold Gilman, ‘Composition in Painting’ The Art News, 12 May 1910, p.218.

- Walter Bayes, ‘The Camden Town Group’ The Saturday Review, 25 January 1930, pp.100–1.

How to cite

Helena Bonett, ‘Nude at a Window c.1912 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, November 2010, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www