Anna Hope Hudson Chateau d'Auppegard After 1927

© The estate of Anna Hope Hudson

Anna Hope Hudson,

Chateau d'Auppegard

After 1927

© The estate of Anna Hope Hudson

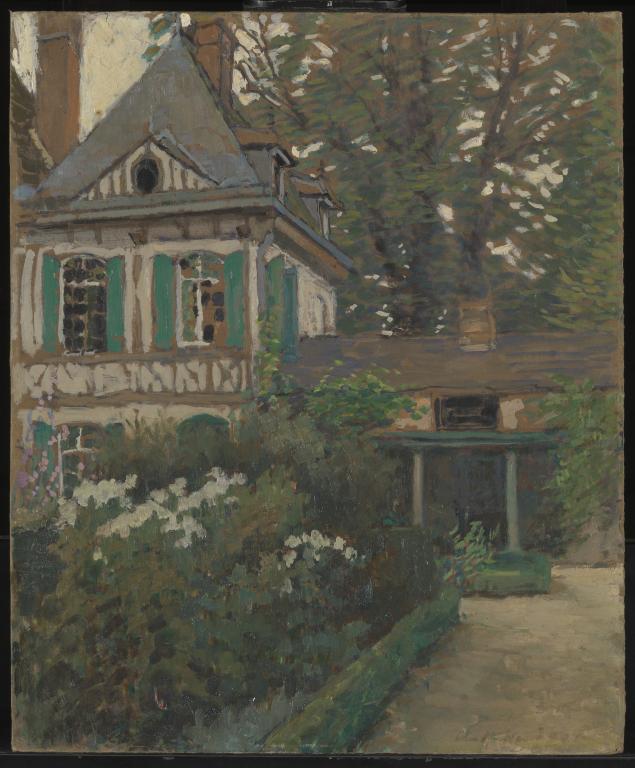

The subject of this painting is the Château d’Auppegard, a large seventeenth-century house with a grey slate gabled roof located ten miles inland from Dieppe in the Normandy countryside, where Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands spent summers together from the 1920s. The two women renovated the dilapidated dwelling, even commissioning murals from the Bloomsbury artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant for the loggia. In this painting, Hudson’s typically restricted palette of cool tones is applied to paper board.

Anna Hope Hudson 1869–1957

Château d’Auppegard

After 1927

Oil paint on board

462 x 382 mm

Inscribed by the artist in brown paint ‘Anna Hope Hudson’ bottom right and on reverse ‘Darling Ethel, from Nan’

Bequeathed by Colonel Christopher Sands 2000, accessioned 2001

T07810

After 1927

Oil paint on board

462 x 382 mm

Inscribed by the artist in brown paint ‘Anna Hope Hudson’ bottom right and on reverse ‘Darling Ethel, from Nan’

Bequeathed by Colonel Christopher Sands 2000, accessioned 2001

T07810

Ownership history

Given by the artist to Ethel Sands; by descent to her nephew Christopher Sands 1962, by whom bequeathed to Tate 2000.

Exhibition history

1977

Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, Fine Art Society, London, April–May 1977 (29).

References

1977

Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1977, p.182.

2004

Alicia Foster, Tate Women Artists, London 2004, p.161.

Technique and condition

Château d’Auppegard is painted in artists’ oil colours on a stout paper board. The board is one piece of 4 mm-thick grey paper millboard with a smooth surface that may have been lightly sized before painting but has no pigmented priming layer. The edges of the board have been unevenly cut and are now dented and the board itself has developed a slight concave warp. There are creases on the front where it has been bent, and on the back are ruled knife marks and losses where it had been used as a cutting board. It is also covered in grime and glue or paste marks from preparing other boards. All of these features appear to predate the painting.

Preliminary and subsequent drawing is loosely carried out in thin blue paint applied directly onto the board with a soft-tipped brush. The main opaque colour areas are applied rapidly in fluid paint as flat thin films to impasted brushstrokes. The building and path are mainly executed in extended brushwork describing the surface planes and architectural details while the foliage of the trees and garden are created with lively dabs of the brush, sometimes smearing wet paint into wet. Some areas are left unpainted leaving the board exposed to function as a neutral mid-tone, notably in the building and background trees. Touches of red and pink in the flora provide accents of colour and are probably made from a colour containing a traditional madder dyestuff. The paint appears to have sunk a little, losing medium into the absorbent board, necessitating the addition of an uneven, thin surface film like a ‘retouching varnish’ to re-saturate the colours. This surface film and any initial sizing have darkened the exposed board face to a warm brown, which will have slightly altered the original tone and colour relationships with the paint.

Roy Perry

November 2003

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', November 2003, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Château d’Auppegard After 1927 by Anna Hope Hudson’, catalogue entry, July 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Anna Hope Hudson, known as Nan, was an expatriate American who had studied painting in Paris and exhibited her work in France and in London. Hudson became friendly with Walter Sickert after he saw and greatly admired one of her paintings, Le Canal de la Giudecca (untraced), exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1906. She was subsequently invited to participate in the Saturday ‘At Homes’ of the Fitzroy Street Group. Although excluded from joining the Camden Town Group owing to the ban on women, she was once again drawn into the circle of London’s avant-garde when the group reformed in 1913, with additional members, as the London Group.

Few examples of her work now survive. Château d’Auppegard, Tate’s only painting by her, was bequeathed by Christopher Sands, the nephew of Hudson’s lifelong friend and partner, Ethel Sands. It is characteristic of the landscapes the artist produced in later life. Although she did on occasion paint interiors and figure studies, her preference always tended towards landscapes with an element of architectural interest. From 1926 she almost exclusively produced French landscapes, choosing subjects found in the area surrounding Auppegard and Dieppe, or viewed while touring other regions of France during the spring or early autumn.

The painting is a typical example of Hudson’s use of a restricted palette with cool tones. The paint has been applied in broken patches on a cardboard ground with areas of the board left untouched, which serve as an integral part of the pictorial structure. Walter Sickert, who boasted that he was ‘sent from heaven to finish all your educations’,1 and who from around 1907 had appointed himself as artistic mentor to Hudson and Sands, repeatedly tried to coach the former away from this style of painting which he called a ‘flicker of gaps’.2 As in his instruction of all his pupils, Sickert advocated only his own method of painting directly from squared-up drawings, away from the subject, and he counseled Hudson not to paint on any other surface but canvas. Although some of Hudson’s paintings do show evidence of an assimilation of Sickert’s lessons, for example The Violin Solo c.1913 (private collection),3 she never abandoned her liking for painting on board. In this she was probably influenced by the work of the French painter Edouard Vuillard, whom both Hudson and Sands knew personally.4 In about 1890 Vuillard had begun to produce small-scale studies using flat notational touches of pigment on an absorbent cardboard base with the grey or buff of the ground used as a colour in its own right. Hudson’s technique also involved building up the image through broad, choppy brushstrokes of fairly dry paint with the untouched areas incorporated into the overall composition. However, her work is more reminiscent of a relaxed late impressionism, for example, Claude Monet’s paintings of his garden at Giverny, than of Vuillard’s highly decorative and symbolic paintings of interiors.

It is impossible to describe the life and career of Hudson without reference to Sands. The two American women met in Paris in 1894 while they were both art students and maintained a very close relationship for over sixty years. The art historian Wendy Baron described them as ‘two independent, individual women with many tastes and interests in common, whose mutual love and understanding rescued them from the loneliness of spinsterhood’.5 Throughout their lives they found it hard to be apart, yet their preference for different lifestyles necessitated periods of separation. As Sands described it, ‘although we love each other so dear, we don’t like the same places, or the same things, or the same people’.6 Hudson was a Francophile. Having left the United States during her twenties she rarely returned to her native country, preferring throughout her life to live, work and travel in France. Conversely, Sands loved England and owned two houses there, a country house at Newington, Oxford, and from 1913 a house in the Vale, Chelsea. The two women adopted the habit of spending months alternating between residences in France and England and, following the First World War, Hudson decided to find a permanent residence in France with the idea that she and Sands could spend the summers there together.7 In the summer of 1920 she leased, and then bought, the Château d’Auppegard, a large seventeenth-century house situated about ten miles inland from Dieppe, near Offranville in the Normandy countryside. It became her principal home until her death, thirty-seven years later, in 1957. She and Sands tended to live there together each year between May and September, holding weekend salons for interesting guests including writers, politicians and artists.8 During the winter Sands returned to England and their letters testify to their unhappiness at being apart. Hudson’s painting Château d’Auppegard is inscribed on the back of the canvas, ‘Darling Ethel, from Nan’, and was perhaps intended to hang in Sands’s house in London and remind her of Auppegard and her friend when the two were separated. Probably owing to its personal nature, the painting seems never to have been exhibited during either woman’s lifetime.

Although Hudson took her painting very seriously, she, like Sands, was a woman of independent means and therefore had no need to earn a living from her art. The two ladies lived very full and busy lives in which painting played a part but was not an all-consuming pursuit, interspersed as it was with travelling, socialising and a love of home decoration and fashion. Such partial commitment to painting proved irritating to Sickert, who wrote to them in 1907: ‘I am a little cross with you both. I thought you were both going to work daily & produce & improve. Otherwise what do you get out of helping to pay for our studio? I meant you to improve by leaps & bounds! What in heaven’s name do you do?’9 One of the things which occupied much of Hudson’s time from 1920 until the last years of her life was the restoration and decoration of the Château d’Auppegard. Although she did continue to paint during the 1920s and 1930s, the majority of her time and energy was devoted to improvements on her beloved home, some of which are recorded in the Tate painting.

When Hudson first arrived at Auppegard in 1920 the château was in a rather neglected condition, so with the help of Sands she threw herself into its complete but sympathetic renovation. Both the interior and exterior needed extensive restoration work for which local craftspeople were hired. All of the designing and decoration of the rooms inside the house were the creative inspiration of the two women. Letters written during 1921 from Sands in England to Hudson at Auppegard, now in Tate Archive, are full of comments about the improvements, advice on the decoration of the house and designs for the garden, domestic problems such as the employment of servants, and references to enclosed patterns for wallpaper and fabric.10 The result of their labours successfully combined period furniture and style with modern colours and taste, and was so remarkable that it merited an article in Vogue, November 1923, by the interior and textile designer Allan Walton (1891–1948). Walton, who was later to become director of the Glasgow School of Art, owned a successful business, manufacturing printed furnishing materials including designs by the Bloomsbury artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. His description of the décor of the rooms at Auppegard provides a thorough account of the château three years after Hudson and Sands had acquired it, and documents the care and attention which the two women had lavished upon it:

By knowledge, experience, and great taste they have added to the original character of the house a most personal flavour. Touches so slight as to pass almost unnoticed – the shaping of a pelmet, the use of some unusual toile, the fixing of a tiny rosette to hold back frilly organdie curtains, all give an air to the beauty of the old house. It is an example of successful characterisation, not merely reproduction. The old is all carefully preserved, the new brings out the flavour of the old ... It is by such touches that Miss Sands and Miss Hudson have given to the house its unique personality. The whole decoration has been kept in a light key: and ample windows, spacious views, muslin and organdie give the old house an airy, happy grace like the pictures painted at the time when it was built. Outside, the orchards and wood smells of Normandy, inside that delicacy and kindly charm which is real comfort.11

Walton would have also approved of further improvements carried out in the years following the Vogue article. In 1927, Sands commissioned Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant to decorate the walls of the loggia adjoining the main building with painted murals of figures in garden settings. These murals still survive today as one of the few extant complete decorative Bloomsbury schemes.12 Sands herself also completed some painted trompe l’oeil decorations for the house inside the bathroom and lavatory.13

In the Vogue article, Walton recorded the exterior of the Château d’Auppegard as ‘an enchanting house of exquisite proportion carried out in the manner of the countryside with steep roof and picturesque half-timbered walls’.14 The French painter Jacques-Emile Blanche, a regular visitor, described the south side with its ‘flower borders, the rock garden, the clipped yews and the lawns, where in former times the cattle belonging to the farm had pastured’.15 Both these descriptions are confirmed in Hudson’s painting of her beloved home, which shows a corner of the château from the south side with the loggia to the right and the garden with its small box hedge borders in the foreground. The shallow depth of the house, only the thickness of one room, is clearly evident, as is the steepness of the grey slate gabled roof, interspersed with dormer windows and tall chimneys. The white plaster and timbered façade of the house is relieved by the extensive fenestration of old Dutch glass windowpanes and rustic green shutters.

The painting has previously been dated after 1920, although there are a number of factors to indicate a later date. The effort of renovating the house and garden absorbed Hudson totally in the early 1920s, and Wendy Baron has noted that it was not until 1926 that she revived an interest in painting when she rented a studio in Dieppe.16 There is also the presence in the painting of the half-timbering along the south face of the house. In 1920, when Hudson first purchased the house, this wall, like the north side, was completely plastered over. Local craftspeople were duly employed to strip the plaster away and reveal the original timber work underneath. The garden, upon which Sands in particular worked very hard and made many improvements,17 appears well developed and fully grown in the painting, suggesting the two women must have been in residence for some years. Furthermore, close inspection of the dark shadows inside the loggia adjoining the château reveals darker patches of paint on the central wall between the two plain Doric columns. These patches indicate the outline of the loggia’s fireplace and above it, a mural decoration by Duncan Grant painted as part of the scheme he executed with Vanessa Bell in 1927. The scene above the fireplace is described by the art historian Simon Watney as ‘an exotic bare-breasted lady with a tall powdered wig, seated as in a box at the opera, holding a pink rose’.18 Only the outline of the opera box and the suggestion of the figure are discernible, but this detail indicates that Hudson’s painting must date from after the completion of the mural scheme in September 1927. It was, however, almost certainly painted before 1940 when the German invasion of France forced Hudson and Sands to abandon Auppegard and flee to England. They were not able to return to Normandy until 1946, after which time Hudson did not paint a great deal.

It may be that no other paintings by Hudson of the château still exist, although there were presumably many others. Very few of her paintings survived the Second World War. A direct hit on Sands’s London home during the Blitz obliterated much of both of their work. Furthermore, Auppegard itself sustained extensive damage from bombing and looting when many drawings and paintings, including a collection of works by Sickert and Augustus John, were stolen, never to be traced. It is likely that paintings by the two owners were therefore lost too. The château does appear as the subject of a number of surviving works by Sands (see Tate T07809). The two women returned to Auppegard in May 1946 and faced the devastation left by the war. Vanessa Bell visited them in September and recorded that:

The house has been terribly damaged by a flying bomb which exploded near. They have managed to repair the worst things and when one drives up to it [it] is still very lovely. But inside only the dining room is usable, and they have hardly any furniture and just enough for themselves. Poor old things – as they say, they are too old to begin all over again and they certainly do look very aged and decrepit.19

Hudson, then in her seventies, devoted much of her time once again to restoring the house to its former glory and she and Sands continued to spend each summer there together. As they grew older it became more of a physical and financial struggle to maintain the château and they worried about its eventual fate.20 It was decided to give the house over to a young friend of theirs, Louis le Breton, on the understanding that it would eventually be bequeathed to the French nation. Le Breton, an amateur painter, had been introduced to the two women as a family friend of Jacques-Emile Blanche. Following active service in the war, he worked in the Department of Oriental Antiquities at the Louvre. He shared Hudson’s passionate love of the house and she was happy that under his care Auppegard would be preserved and cherished after she was gone. She and Sands continued to live at the château within a specially adapted self-contained apartment. Unfortunately, their careful planning was to no avail since Louis le Breton pre-deceased both of them, dying suddenly in the garden at Auppegard in March 1957. Hudson herself had by this time become too ill to live there and was cared for at a nursing home in Kilburn, dying just a few months later in September 1957 aged eighty-eight. Her funeral was held at Auppegard and she was buried in the churchyard facing her beloved château.

Nicola Moorby

July 2003

Notes

Reproduced in The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (112).

Jacques-Emile Blanche, More Portraits of a Lifetime: 1918–1939, trans. and ed. by Walter Clement, London 1939, p.109.

Allan Walton, ‘The Château d’Auppegard, a Louis Quatorze Country House’, Vogue, November 1923, pp.48–50.

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Château d’Auppegard After 1927 by Anna Hope Hudson’, catalogue entry, July 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www