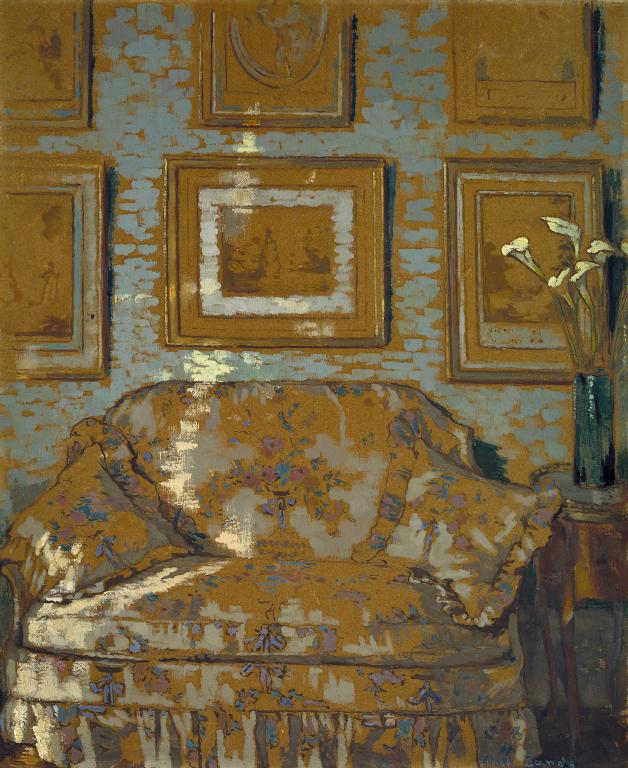

Ethel Sands The Chintz Couch c.1910-1

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Ethel Sands,

The Chintz Couch

c.1910-1

© The estate of Ethel Sands

Ethel Sands inherited a fortune that enabled her to live an independent life, painting, travelling and socialising. In this painting she depicts the interior of her home in Belgravia, London, richly decorated with a number of framed landscapes and a delicate arrangement of long-stemmed white arum lilies beside a large chintz sofa. The objects presented combine both old-fashioned and modern tastes, reflecting the personality of the artist.

Ethel Sands 1873–1962

The Chintz Couch

c.1910–11

Oil paint on board

465 x 385 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Ethel Sands’ in blue paint bottom right

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

N03845

c.1910–11

Oil paint on board

465 x 385 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Ethel Sands’ in blue paint bottom right

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

N03845

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to the Contemporary Art Society 1911, by whom presented to Tate Gallery 1924.

Exhibition history

1911

Loan Exhibition of Modern Pictures, Drawings, Bronzes, Etchings and Lithographs, Municipal Art Gallery, Kingston upon Thames, July–September 1911 (28).

1911–12

Loan Exhibition of Works Organised by the Contemporary Art Society, Manchester City Art Gallery, December 1911–January 1912 (49).

1912

Loan Collection of Modern Paintings Organised by the Contemporary Art Society, Laing Art Gallery and Museum, Newcastle upon Tyne, October 1912 (224).

1913

Contemporary Art Society: First Public Exhibition in London, Goupil Gallery, London, April 1913 (15).

1914

Twentieth Century Art, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, May–June 1914 (332).

1923

Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings held at Grosvenor House, Contemporary Art Society, London, June–July 1923 (153, as ‘An Interior’).

1946

The Contemporary Art Society: An Exhibition of a Selection of the Acquisitions of the Contemporary Art Society from its Foundation in 1910 up to the Present Day, Tate Gallery, London, September–October 1946 (63, as ‘Interior’).

1960

Contemporary Art Society 50th Anniversary Exhibition, Tate Gallery, London, April–May 1960 (64).

1976

Camden Town Recalled, Fine Art Society, London, October–November 1976, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, November–December 1976 (122).

1977

Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, Fine Art Society, London, April–May 1977 (3).

1994–5

Archive Acquisitions 1990–1994, Tate Gallery, London, November 1994–March 1995 (no number).

References

1920

Contemporary Art Society Report for the Years 1914–19, London 1920, p.7.

1924

Contemporary Art Society Report for the Years 1919–24, London 1924, pp.8, as Interior, 12, as The Chintz Couch.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.585–6.

1977

Wendy Baron, Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1977, p.85.

1991

Alan Bowness, Judith Collins, Richard Cork et al., British Contemporary Art 1910–1990: Eighty Years of Collecting by the Contemporary Art Society, London 1991, p.20.

1991

Maud Sulter, Echo: Works by Women Artists 1850–1940, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, Liverpool 1991, pp.10–11, reproduced.

2001

David Peters Corbett, Walter Sickert, London 2001, p.44, reproduced p.43.

2004

Alicia Foster, Tate Women Artists, London 2004, p.161, reproduced.

Technique and condition

The Chintz Couch is painted on laminated mixed-fibre grey paper board, which was cut on all four sides before painting to form its current dimensions. There are a number of scuffs and cut marks in the surface but these appear to have been present before painting. The board has been sized but has not been primed.

The artist drew directly onto the board in a graphic medium, faint traces of which remain in areas such as the framed pictures at the left-hand side. She strengthened this drawing with pen and ink, establishing the main compositional elements. Sands used the colour of the board as the basis of the colour of the main forms, the sofa, the wall and the pictures, applying paint sparingly in patches or as touches of coloured detail and ruled lines to delineate edges, such as the frame mouldings. In the later stages, bright tints are touched in over existing colour as well as unpainted board, such as the flecks of sunlight on the left side of the sofa and wall, and lights and shadows marked in with a fairly dry brush providing lively contrast with the smooth flat surface of the board. Single touches of one colour retain distinctive brushworking, where the oil medium has sunk into the board leaving a dark halo around each brushstroke. The overall loss of medium to the board has also resulted in the paint drying to a consistently matt surface, which has never been varnished. A handwritten inscription on a historical commercial packing label attached to the back identifies the work as ‘Interior’.

Roy Perry

September 2004

How to cite

Roy Perry, 'Technique and Condition', September 2004, in Nicola Moorby, ‘The Chintz Couch c.1910–11 by Ethel Sands’, catalogue entry, September 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Many of the interiors painted by artists of the Fitzroy Street and Camden Town circles reflected the humble and financially straitened reality of their own lives, for example Spencer Gore’s The Gas Cooker 1913 (Tate T00496). The Chintz Couch by Ethel Sands, however, depicts an unashamedly elegant and fashionable interior representing a life of leisure and material wealth. The painting shows one part of a room with a small couch covered in chintz material, standing against a wall hung with a number of framed pictures and prints, none of which has been identified. To the right of the couch there is a side table upon which is placed a tall blue glass vase holding an arrangement of white arum lilies. A band of white light streaks across the left-hand side of the couch and continues up the wall, suggesting a window with curtains partly open on one side. Sands has used a sparing, dry application of paint, and the colour of the largely uncovered board plays a major part in the colour and tonal relationships of the painting.

Sands inherited a comfortable fortune after the premature deaths of both of her parents which enabled her to live an independent life, painting, travelling, socialising and entertaining. Women who wished to pursue a professional artistic career at the turn of the century often faced the practical difficulty of finding sufficient funds to finance a decent artistic education. At the Académie Julian in Paris, for example, the fees for women were double those charged to male students.1 Sands’s private income gave her the economic resources to practise art and the subjects of her paintings reflect her experience as an affluent and intelligent woman at the beginning of the twentieth century, unhindered by the pressures of earning a living or raising a family. Like many of her contemporaries, she chose to paint subjects drawn from everyday life but, in her case, not an everyday life which was accessible to many. It was the reality of her own privileged existence which provided the inspiration for her art and she frequently depicted scenes set within her various homes, in Oxfordshire, London and later in France.

From 1898 Sands owned the lease on a large seventeenth-century manor house at Newington in Oxfordshire where she lived, in between sojourns in France with Nan Hudson, until 1920. It was at Newington that Sands established a reputation as one of the most important society hostesses of the day, entertaining not only family and close friends but some of the great intellectual and artistic figures of the day such as Henry James, Roger Fry, Augustus John and Lady Ottoline Morrell. Despite the regularity of these weekend gatherings, her love of interesting company and cultural entertainment was not fully satisfied by the quiet local village life and she craved the exciting diversions and stimulating society of London. In 1906, when her younger brother Morton announced his intention to enter politics, Sands decided that this was the necessary justification for owning a residence in the capital and she duly purchased a large town house at 42 Lowndes Street in exclusive Belgravia.2 In 1958, in response to an enquiry, she wrote to the Tate Gallery that it was at this address that she painted The Chintz Couch, in around 1910.3

Throughout her life, Sands combined a broad-minded acceptance of modern tastes and innovations with an anachronistic love of old-fashioned refinement and modes of conduct. The interior décor of her various residences favoured traditional period schemes but she also had an experimental interest in contemporary design. For example, in 1913, after she moved from Lowndes Street to a house in the Vale, Chelsea, she commissioned her friend Walter Sickert and the Russian mosaic artist Boris Anrep (1883–1969) to execute decorative commissions for her. The interior seen in The Chintz Couch represents both aspects of her individual style. The formal layout of the room and the close multiple hanging of small framed pictures on the wall behind the couch is reminiscent of an eighteenth-century drawing room, while the relative simplicity of the arrangement of tall, white lilies is a modern touch. The pictures themselves look to be a selection of historic landscape engravings and figure subjects, although Sands was also known to collect works by modern artists such as Sickert and Augustus John and Japanese panels which were then in vogue.4 The eponymous chintz couch is both contemporary and traditional. Chintz had been popular in Britain for over two hundred years and was still the choice of well-to-do households prior to the First World War.5 It was also a very fashionable style in wealthy homes in the United States at this time.6 Sands may possibly have picked up a liking for the fabric from her American mother, Mary Morton Sands, who was herself a well-known and fashionable society hostess in New York and London in her day.

Chintz is a heavy cotton material characterised by distinctive, colourful patterns, usually based upon floral motifs and the glossy, sheened surface texture of the cloth. In previous centuries it was one of the most popular and versatile furnishing fabrics. Despite its quintessentially English reputation, it was first imported to Europe from India during the seventeenth century and its name derives from a Hindi word, ‘chitta’, meaning variegated or many coloured. Initially an expensive luxury item, chintz became the decorative choice for aristocratic country homes in the eighteenth century and it went on to enjoy widespread popularity during the nineteenth century following advances in mass manufacturing.7 At the beginning of the twentieth century, there was a particular vogue for re-upholstering reproduction furniture with loose chintz covers and large comfortable cushions to create a look combining eighteenth-century elegance with a modern desire for comfort.8

Many of the chintz designs available on the market at the beginning of the twentieth century were roller or block-printed fabrics based upon traditional historical patterns and featured soft, faded colours and eighteenth-century motifs such as garlands, swags and bouquets of flowers, ribbons and classical urns.9 The couch in Sands’s painting features a repeated design composed of a spray of pink and blue flowers, possibly roses, in a tall shallow vase festooned with a ribbon. This has been identified by the Warner Archive as a fabric manufactured and sold by the prestigious furnishings company Warner & Sons and designed by Hazel Wray Davey, a freelance designer for the firm from 1908–35.10 Warner & Sons had been founded in Braintree, Essex in 1870 and specialised in traditional patterns based on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sources although the company also employed a number of contemporary designers such as Owen Jones, Walter Crane and E.W. Godwin.11 It is likely that Sands purchased the fabric from one of London’s large department stores such as Liberty & Co. and Debenhams & Freebody to whom Warners were a supplier.12 Evidently Sands was genuinely fond of chintz since it appears as a feature in other paintings of her domestic environment such as Tea with Sickert (Tate T07808).

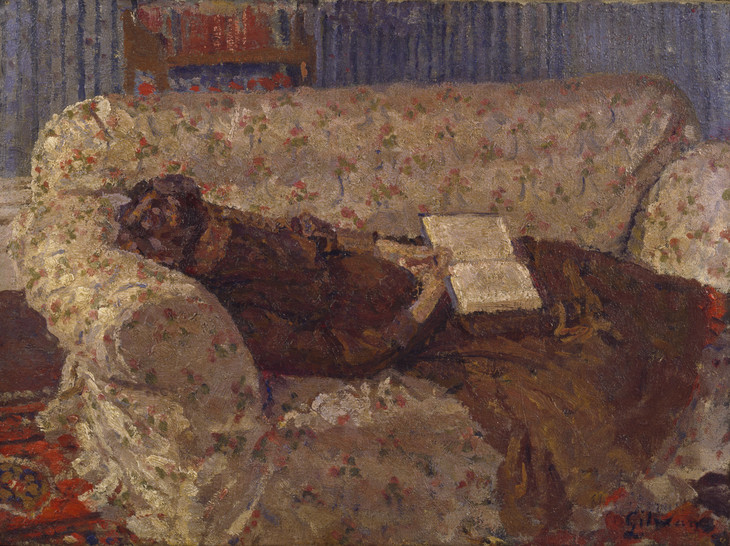

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Lady on a Sofa c.1910

Oil paint on canvas

support: 305 x 406 mm; frame: 475 x 578 x 100 mm

Tate N05831

Purchased 1948

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

Lady on a Sofa c.1910

Tate N05831

Jacques-Emile Blanche 1861–1942

Le Divan en chintz 1908

Oil paint on canvas

50 x 61 cm

Unknown private collection. All rights reserved

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2010

Fig.2

Jacques-Emile Blanche

Le Divan en chintz 1908

Unknown private collection. All rights reserved

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2010

Chintz was particularly used to furnish rooms traditionally under the jurisdiction of the lady of the house, such as the sitting room or drawing room where visitors would have been received and entertained. Just as flower painting had long been considered a suitable genre for women artists, the ornamental floral patterns and light, attractive colours of chintz became characteristic of feminine interior space and a decorative, passive sort of domesticity. The fabric was perceived to represent a set of values synonymous with genteel middle-class refinement and comfort, an English love of nature and an appropriately feminine taste for prettiness and adornment. A contemporary article in Everywoman’s Encyclopaedia even recommended that women should coordinate their chintz with the colour of their eyes,13 suggesting that the domestic decorative scheme should provide a suitably personalised space within which the routine rituals of respectable middle-class life are played out. Many artists painted portraits which featured women against appropriately feminine, chintz-covered backdrops, for example The Blue Dress 1911 (Tate N04099) by Sir Walter Russell (1867–1949), Rosamund and the Purple Jar exhibited 1900 (Tate N03717) by Henry Tonks (1862–1937), and Harold Gilman’s Lady on a Sofa exhibited 1910 (Tate N05831, fig.1). Sands may also have found a precedent for the subject in the work of the French painter Jacques-Emile Blanche (1861–1942), whom she had known as a friend for many years. He painted at least two pictures dating from 1907–8 titled Le Divan en chintz (fig.2).14 The paintings assume the same viewpoint as Sands’s later composition, with the sofa viewed square-on and a set of framed pictures arranged on the wall behind. Sands and Blanche knew each other well and were frequently houseguests at each other’s residences so it is extremely likely that she was familiar with his work. The interior of The Chintz Couch is undoubtedly intended to represent a space that belongs particularly to a woman, similar to that of Lady on a Sofa but without the physical appearance of a female figure. The woman in question is, of course, standing to paint the picture but her presence is nevertheless explicitly evident through the material objects of her everyday environment.

Sands loved the process and preoccupations of projecting her taste and personality upon her surroundings and attempted to make her homes almost works of art in themselves.15 This desire, which was awakened at Newington, reached its fullest expression at the French château of Auppegard during the 1920s and 1930s (see Tate T07809 and Nan Hudson, Château d’Auppegard, Tate T07810). Vanessa Bell, who like many of the Bloomsbury circle was a regular visitor to Newington and Lowndes Street, remarked on the ‘excessive elegance and 18th century stamp’ of the lifestyle and environment of Sands and her partner, Nan Hudson. 16 Writing to Roger Fry in 1912 she voiced her opposition to their inclusion in the Omega Workshops project:

It isn’t what we want even for our minor arts is it? Won’t they import too much of that? Of course I know they’re useful, but I do think we shall have to be careful, especially in England where it seems to me one can never get away from all this fatal prettiness. Can’t we paint stuffs, etc., which won’t be gay and pretty? I see how easy it would be to turn out yards of very fanciful and bright and piquant things, and I don’t see what else that couple can do ... I must say that seeing them in their own chosen surroundings did give me rather the creeps, at least when I thought of bringing that into anything to do with art. Does that sound priggish?17

Despite Bell’s reservations about the suffocating effect of Sands’s ‘chosen surroundings’ upon her artistic abilities, The Chintz Couch should be understood as a statement of independent personality and a commitment to the values of modern living. In a famous essay of 1929, Bell’s sister Virginia Woolf argued that a woman’s creative and intellectual freedom depended upon a degree of financial independence and ‘a room of one’s own’.18 The Chintz Couch pre-dates Woolf’s text by almost twenty years but is a visual expression of a similar idea. Sands represents and celebrates the domestic interior as both the site and theme of personal and uninhibited creativity. There is a sense of pride and aesthetic pleasure in the tasteful arrangement of the furniture and choice of furnishings. Any overt prettiness or sentimentality suggested by the sofa’s chintz covering is played down by the artist’s careful use of a controlled, cool palette and the visual contrast of the stark white lilies standing in a vase nearby. The care with which Sands decorated and then pictorially represented her home is evidence, not of slavish and repressive conformity, but of individual expression and a confident modern interest in the domestic sphere.

Sands presented this painting to the Contemporary Art Society in 1911. Initially known as the Modern Art Association, the Contemporary Art Society was established in 1909 as an independent committee for the encouragement of modern artists through the purchase and exhibition of their works.19 As the art historian Wendy Baron has noted, it was probably no coincidence that the committee which accepted The Chintz Couch included a number of Sands’s close friends and acquaintances including Lady Ottoline Morrell and Roger Fry.20 Nevertheless, when the painting was presented to the Tate Gallery in 1924 it represented a notable addition to the collection, remaining the only example of the artist’s work until a bequest by her nephew, Colonel Christopher Sands, over seventy-five years later.

Nicola Moorby

September 2003

Notes

Information supplied by Lesley Hoskins, Curator, Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, Middlesex University, April 2003.

Hilary Hockman, Edwardian House Style: An Architectural and Interior Design Source, Newton Abbot 1994, p.98.

Mary Schoeser and Celia Rufey, English and American Textiles from 1790 to the Present, London 1989, pp.143–4.

The 1907 version is reproduced in Jacques-Emile Blanche, peintre (1861–1924), exhibition catalogue, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen 1998, p.154.

Vanessa Bell, letter to Roger Fry, 21 July 1912, in Regina Marler (ed.), Selected Letters of Vanessa Bell, New York 1993, p.121.

Related biographies

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘The Chintz Couch c.1910–11 by Ethel Sands’, catalogue entry, September 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www