Courtesy Petrit Halilaj. Photo: Angela B. Suarez

It seems as if something is burning inside. The stress never sleeps, it’s cold outside, but it is raining warm rain inside. Very volcanic over this green feather.

Petrit Halilaj

In April 1999 Petrit Halilaj made thirty-eight drawings using coloured felt-tip pens on paper. He was thirteen years old and living with his family at the Kukës II refugee camp in Albania, displaced by the Kosovo War. Halilaj has revisited these childhood drawings in his new installation at Tate St Ives. The images are magnified and rearranged as monumental hanging cut-outs in the gallery, combining poignant images of rural landscapes and animals with scenes of war and violence. Very volcanic over this green feather is Halilaj’s act of reshaping painful fragments of memory into a new understanding. This presentation of his personal history aims to make visible the collective trauma of the Kosovar Albanian people and other survivors of war. From the injustices of violence and conflict, Halilaj brings forward human resilience, courage and hope for healing and reclaiming the future.

The installation retells Halilaj’s traumatic experience of the Kosovo War, wrapped with his dreamlike visions of escape. His hallucinatory landscape with soaring birds, animals and symbols of places far away is entangled with fragments of conflict. Towards the centre of the space, a figure of a child is enlarged from a picture that Halilaj created for Kofi Annan who visited Kukës II as Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN). Hallilaj hoped his drawing could broadcast what was happening and help to stop the war.

From the way a child draws, we can get important information about their feelings and state of mind: from the size of the objects, people, themselves, a tree, the choice of drawing it up, down, left or right, the fact that all the members of the family are there or that some are absent and others added, their position, the space they leave empty

Giacomo Poli

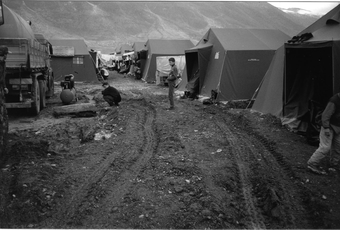

Petrit (centre left) presenting his drawing to Kofi Annan at Kukës II, Albania. 20 May 1999 Source: https://bit.ly/3BxoXcc

I prepared this drawing for Kofi Annan’s visit, believing that it could show what we all had experienced through the war and that he could stop it. My grandfather, Osman Halilaj, was convinced that Kofi Annan’s visit was too late, or even just a ‘theatre play’, and that it would not change anything. Because of his skepticism, I ultimately decided to keep the drawing, although I had planned to give it to Kofi Annan in the first place.

Petrit Halilaj, 2021

REALITIES AND FICTIONS

Halilaj’s thirty-eight drawings were made under the guidance of Giacomo Poli, an Italian Psychologist of Emergencies. In April 1999 Poli distributed art materials to Halilaj and other children at the Kukës II refugee camp. Through drawing, Poli supported the children to process experiences that could not be expressed in words. He encouraged the children to imagine alternative futures and resolutions to the conflict they witnessed, as a method for coping and healing from trauma. In 2020 Halilaj rediscovered the drawings he made at the camp, now preserved in Poli’s archive. He also revisited the picture he drew for Kofi Annan, cared for by artist Ymer Metalia in the archive of the Lezhë Art Gallery, Albania. Together, Halilaj and Poli selected, cut out and rearranged elements from Halilaj’s childhood drawings. The images hanging in the installation are clustered around their shared memories of the Kukës II camp.

Fictions are also sometimes part of our inner world and help determine both our emotions and our behaviour. Each of us interprets reality in a personal way ... so, what is real for one, is not real for another.

Giacomo Poli

CONFLICT AND THE KOSOVO WAR

Kukës II refugee camp, Albania, April 1999. Photo: Giacomo Poli

Kosovo’s independence as an Autonomous Province was diminished during the 1980s. Peaceful mass protests rejected the increasing losses of self-rule that were imposed under Serbian sovereignty. In 1989 Serbia abolished Kosovo’s autonomous status and increased the presence of Yugoslav forces in the region. Protests escalated into armed conflict in Kosovo across the following decade. In 1997–8 a campaign of destruction and violence by Serb police and Yugoslav military forces killed an estimated two thousand ethnic Kosovar Albanian people, inciting the Kosovo War. The Kosovo War is recorded as beginning between January and March 1998 and ending in June 1999. The Kosovo Liberation Army fought forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in an uprising against the persecution of Kosovar Albanians. During 1998–9 Petrit Halilaj and his family sheltered in cities across Kosovo as they travelled to Albania to find refuge at the Kukës II and Lezhë-Shëngjin camps.

INTERNATIONAL INTERVENTIONS

Photo: Andrew Testa 1999

After contentious negotiations and failed international diplomacy, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) intervened in the Kosovo War in early 1999. The NATO airstrikes on Serbia’s military targets remain controversial. The campaign commenced without approval by the United Nations (UN) Security Council and caused a recorded 488 deaths, including many refugees. During the 78 days of sustained NATO air bombardment, retaliation by Yugoslav forces killed an estimated 10,000 Kosovar Albanians and displaced 850,000 civilians.1 Withdrawal from Kosovo was agreed on 9 June 1999 by the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the Republic of Serbia, to allow an international military and civilian presence. The UN was tasked to establish a protectorate and administrate the ‘substantial autonomy and self-government’2 of Kosovo.

Here I was, in line with the others at the Kukës II refugee camp, waiting for food. I didn’t notice Andrew Testa taking this picture and I didn’t see it until over a decade later, when I found it accidentally on the website of the New York Times.

Petrit Halilaj, 2021

POST-WAR INDEPENDENCE

Map: Peter Fitzgerald 2009. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Kosovo declared independence from Serbia on 17 February 2008, coordinated with NATO’s decision-making ‘Quint’ group, consisting of France, Germany, Italy, the UK and the US. Over half of the 193 UN member states recognised the proclamation, including 3 permanent members of the UN Security Council: France, the UK and the US. Map: Peter Fitzgerald 2009. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0The United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo transferred authority to the established Kosovo government in 2008. Kosovo also became a member of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, the International Olympic Committee, and FIFA. The independence of Kosovo is recognised by 117 of the 193 UN member states in 2021.

The Kosovo War and its aftermath caused the estimated displacement of over one million Kosovar Albanian people. A Humanitarian Law Centre database documents the names of 13,535 victims of the war, including 10,812 Kosovar Albanians; 2,197 Serbs; 526 Roma, Bosniaks and non-Albanians; and a further 1,603 missing people whose war-victim status is unconfirmed. Most were civilians.

WAR CRIMES AND CONVICTIONS

The Hague International Court of Justice established that Yugoslav forces had attempted to ‘remove’ the Albanian population of Kosovo in a ‘deliberate campaign of ethnic cleansing’. In 2011, it convicted Serbian Police General Vlastimir Đorđević for the ‘Forcible Transfer, Deportation, and Murder’ of Kosovar Albanians ‘on the basis of their ethnicity’, and for his leadership of a ‘campaign by Serbian forces, which included the systematic damage and destruction of cultural monuments and Muslim sacred sites of the Kosovo Albanian population.’ The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) indicted 161 individuals and convicted 90 ‘for serious violations of international humanitarian law’ committed in former Yugoslavia during the 1990s. This included Slobodan Milošević (then President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia), the first sitting head of state to be charged with war crimes by an international tribunal. Trials for war crimes perpetrated in Kosovo during the 1980s–90s continue at The Hague and in state courts. In 2021 the government of Kosovo stated its intent to sue Serbia for crimes of genocide, through the International Court of Justice.

THEN TO NOW

Petrit Hailaj and Giacomo Poli, Kukës II refugee camp, Albania. April 1999 Courtesy of Giacomo Poli

Giacomo Poli is a psychologist, psychotherapist and psychodramatist. In 1999 he took part in the Lombardy Region’s ‘Missione Arcobaleno’ (Rainbow Mission) to help the Kosovar population during the war. He studied the Psychology of Emergencies, joining the NGO ‘Psicologi per i Popoli’ (Psychologists for People) during the 2009 earthquake in Abruzzo, Italy. Petrit Hailaj and Giacomo Poli, Kukës II refugee camp, Albania. April 1999 Courtesy of Giacomo Poli Petrit Halilaj and Giacomo ‘Angelo’ Poli remain in contact. Poli has supported Halilaj to pursue his artistic career, including helping him to secure scholarships to study and live in Italy.

Poli continues to live in Lombardy, northern Italy, where he welcomes Halilaj’s visits. They regard each other as family.

PETRIT HALILAJ

Petrit Halilaj (born 1986 in Kostërrc, Kosovo) lives and works between Germany, Kosovo and Italy. He is a Studio Professor at l’École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, France. Emerging from his personal experiences, Halilaj’s work is deeply connected with the recent history of Kosovo and the political and cultural tensions in the region. His practice instrumentalises museum exhibition-making to reflect on individual and collective memories, freedoms and identities, and the re-evaluation of private and public histories.