One of the most radical artists of her generation, Ithell Colquhoun was an important figure in British Surrealism during the 1930s and 1940s. An innovative writer and practicing occultist, Colquhoun charted her own course, investigating surrealist methods of unconscious picture-making and fearlessly delving into the realms of myth and magic.

Colquhoun explored the possibilities of a divine feminine power as a path to personal fulfilment and societal transformation. Her understanding of the world as a connected spiritual cosmos brought her to Cornwall, where she deepened her creative explorations, inspired by the region’s ancient landscape, Celtic traditions, and sacred sites.

This landmark exhibition of over 200 artworks and archival materials traces Colquhoun’s evolution, from her early student work and engagement with the surrealist movement, to her fascination with the intertwining realms of art, sexual identity, ecology and occultism. It culminates in a room dedicated to Colquhoun’s interpretation of the Tarot deck – her most accomplished fusion of her artistic and magical practice.

Explore Colquhoun’s enthralling, multi-layered universe through writings, drawings, paintings, early theatre projects and mural designs, many of which have never been shown publicly before.

The exhibition will debut at Tate St Ives in February 2025, journeying to Tate Britain from June to October 2025.

Ithell Colquhoun is in partnership with Lockton. With additional support from the Ithell Colquhoun Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council and Tate Members.

INTRODUCTION

Ithell Colquhoun was one of the most radical artists of her generation. An important figure in British surrealism during the 1930s and 1940s, she was also an innovative writer and practicing occultist who charted her own course between the worlds of art and magic. Her work was multi-layered and boundary defying, responding to profound social change, shifting belief systems and technological advancements in the twentieth century. It proposed an expanded spiritual and natural universe, while introducing complex ideas about gender and sexuality.

Colquhoun turned to magic in her search for divine self-fulfilment and societal renewal. Born in Shillong, India to a British military family, but raised in Cheltenham, UK, she looked to a range of philosophies from across the world. Informed by modern occult movements seeking spiritual truth, she used and reinterpreted ideas from ancient wisdoms such as the Jewish Kabbalah, Christian mysticism, Egyptian mythology and Indian Tantra.

Colquhoun was also attracted to surrealism’s focus on the unconscious, dreamworlds and taboo subject matter. She recognised overlaps between surrealist methods of automatic picture-making and occult divination rituals seeking knowledge of unseen spirit worlds. Her chance experiments often led to imagery suggesting erotic bodies and landscapes infused with sacred feminine power. From the 1940s, her interest in myth and magic brought her to West Cornwall, where she was inspired by ancient sacred sites and Celtic folklore.

This exhibition details Colquhoun’s evolution from her student work and engagement with surrealism to her fascination with the intertwining realms of art, sexual identity, ecology and occultism. It draws on the artist’s personal archive of writings, automatic drawings and magical exercises, the majority of which have never been shown publicly before.

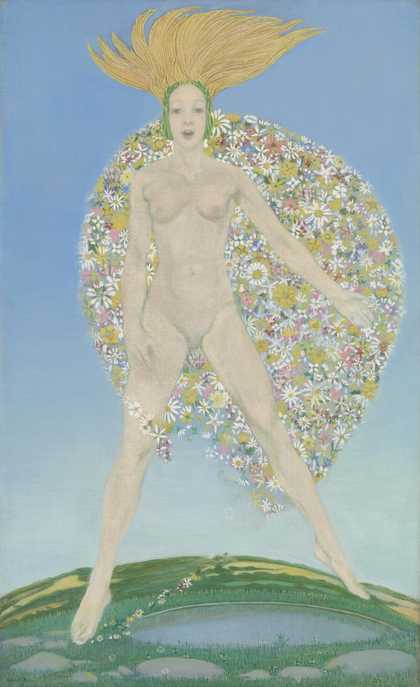

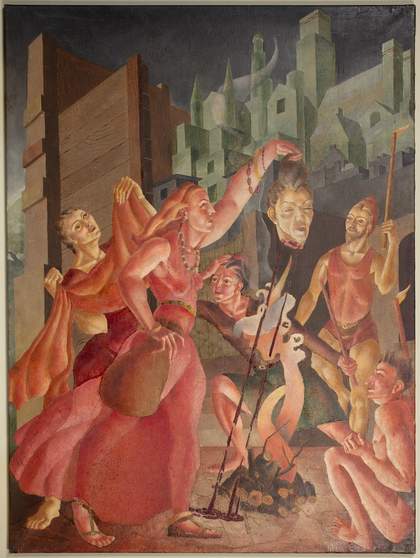

Ithell Colquhoun Judith Showing the Head of Holofernes, 1929 © UCL Art Museum, © University College London, © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans

EARLY YEARS

Colquhoun’s formative years coincided with the aftermath of the First World War, a period of growing resistance to colonial power and shifting gender roles. Living in Cheltenham, away from her birthplace in Shillong where her father had worked in the British Raj’s Indian Civil Service, she wrote of her longing for Hindu traditions. She made sense of her position through artistic expression and alternative spirituality, taking advantage of new opportunities for women to access art schools and magical societies.

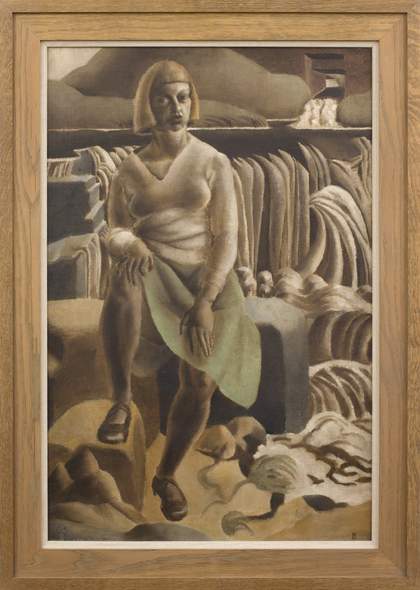

Colquhoun attended Cheltenham School of Arts and Crafts from 1925–7, focusing on painting, architectural design and theatre. From 1927–30, she studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. There she made paintings of classical or biblical subjects, yet also incorporated occult themes. Many emphasise feminine power and include self-portraits, signalling her own subversive agency as a female subject.

Colquhoun used her academic training to give her spiritual ideas a public presence, showing work in group exhibitions and participating in a revival of mural and decorative painting. In parallel, she joined alternative spiritual groups such as the Quest Society. She was also inspired by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, an influential order that taught ritual magic to men and women equally.

Following her studies, Colquhoun travelled in France and the Mediterranean. In Greece she became infatuated with a woman named Andromaque Kazou, capturing her desire in the unpublished story ‘Lesbian Shore’.

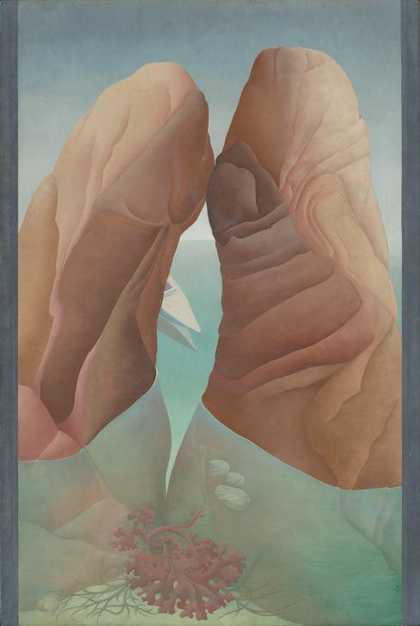

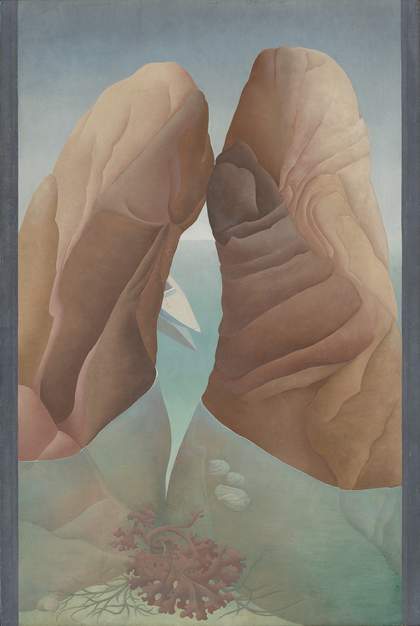

Ithell Colquhoun Scylla 1938. Photo: Tate

INTO SURREALISM

This section charts Colquhoun’s development as she engaged with surrealist groups in the UK and France in the 1930s. Surrealism was a transnational artistic, literary and philosophical movement that explored the workings of the mind, championing the irrational, the poetic and the revolutionary.

Colquhoun was drawn to surrealism for its radical deconstruction of societal norms, coupled with the incorporation of occult concepts advocated by André Breton, a poet and chief spokesperson of the movement in France. She visited Paris in 1931, where she was inspired by Salvador Dalí’s use of illusionary realism and dream-based imagery. Colquhoun was reacquainted with Dalí’s paintings in 1936 at the International Surrealist Exhibition in London, organised by critic and artist Roland Penrose and poet David Gascoyne.

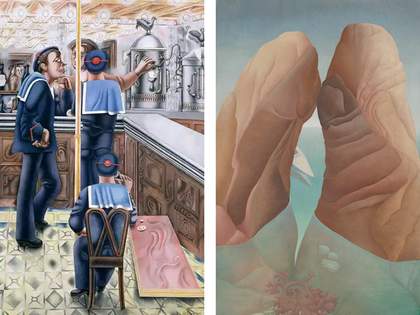

In 1939, she joined the Surrealist Group in England. She also produced Bonsoir, a collage series designed as a storyboard for a surrealist film. She held a joint exhibition that same year with Penrose at the Mayor Gallery in London, showing many of the paintings in this section. They feature architectural, botanical and bodily motifs carried forward from earlier works, now reinterpreted through the lens of surrealism. Reflecting the notion of the ‘double image’, natural forms become uncanny and fantastical, holding multiple symbolic meanings. Many works explore alternative narratives of sexual power, centring on female liberation but also male disempowerment and societal decay.

Ithell Colquhoun, Gorgon, 1946, Private Collection © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans

THE MANTIC STAIN

A turning point came in 1939 when Colquhoun travelled to Chemillieu, France for a gathering of international surrealists including British artist Gordon Onslow-Ford and Chilean-born Roberto Matta. There they expanded the idea of ‘psychic automatism’, the creation of art without conscious thought described by Breton in his First Surrealist Manifesto (1924). Their new ‘psychological morphology’ aimed to chart mystical aspects of the external world as well as the human psyche.

This shaped Colquhoun’s artistic and occultist practice through the 1940s. Moving beyond ‘double images’ of the natural world, her works began to explore inner landscapes and the possibility of a multi-dimensional universe. In her essay ‘The Mantic Stain’ (1949), she compared automatism to forms of divination – the idea of perceiving future events or things beyond our earthly senses – such as crystal ball reading. She embellished many of the chance compositions shown here with conscious adaptations, developing an ‘interpreted’ automatism from which erotic and mythical figures emerge.

Colquhoun’s first experiments in automatism corresponded with a crisis in surrealism triggered by the Second World War. In Britain, the Surrealist Group narrowed its focus and prohibited members from joining other societies including occult orders, which led Colquhoun to break with them in 1940. She continued to interact with international surrealism, identifying particularly with Breton, who saw myth and magic as pathways to humanity’s redemption in the wake of global conflict.

MAGICAL WORKINGS

Colquhoun was influenced by the ‘Occult Revival’, a subcultural movement in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries that looked to ancient practices and modern science in pursuit of spiritual evolution. She was informed by the Theosophical Society, which advocated that all religions are connected by a core spiritual truth. She also followed the teachings and practice-based rituals of the Golden Dawn, embracing the Jewish Kabbalah, Christian mysticism, ancient Egyptian religions, and Tantric doctrines in Hinduism and Buddhism.

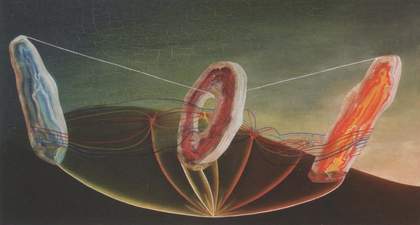

This section compiles Colquhoun’s ‘magical workings’, drawings and diagrams that creatively reinterpret these ideas. While many were likely made for personal spiritual progression, some were exhibited publicly, indicating her intention to share her discoveries. In Diagrams of Love (c.1939–42), shown with her poem of the same name, Colquhoun illustrated ideas of sacred sexual union, or ‘sex magic’. She drew on alchemy, which in spiritual terms refers to divine transformation. Some drawings focus on ‘alchemical union’, the joining of masculine and feminine sexual energies into a perfected whole transcending gender. She also explored same-sex desire and women’s sensual pleasure as paths to achieving enlightenment.

Other drawings reference the Tree of Life, a symbol from Jewish mysticism outlining hidden correspondences between human life, nature and the spirit world. For Colquhoun, divine energy was not limited to physical bodies but also existed as colours and shapes. This is expressed in drawings of the tesseract – the geometrical concept of a four-dimensional cube – which she felt represented access to alternative planes of existence.

Ithell Colqhoun The Sunset Birth, c. 1942 Paul Conran Collection © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans

EARTH ENERGIES

Colquhoun understood the universe as a unified whole, seeing interconnections between animal, vegetable and mineral worlds all infused with divine energy. She wrote about nature as a living being, inscribed with traces of sacred rituals enacted by ancient civilisations attuned to a spiritual conception of ecology.

Colquhoun divided her time between London and Cornwall from the 1940s, renting a studio in Lamorna from 1949 before moving more permanently to a cottage in nearby Paul in 1959. Here she was able to root her mystical ideas in a specific place. As recounted in her book The Living Stones: Cornwall (1957), she explored the region’s Celtic monuments, believing that Britain’s Druid ancestors had made them as outlets for subterranean power channels. Concerned with environmental preservation, she felt that modernisation was destroying the sensitive equilibrium between the mythic history and earth energies which defined the landscape’s restorative power. She joined various Celtic societies, including the Ancient Order of Druids, the Golden Section and the Fellowship of Isis.

This section centres on Colquhoun’s visionary interpretations of Neolithic monuments such as the Merry Maidens and Mên-an-Tol in Cornwall and others in Ireland and Brittany. They are shown alongside depictions of plant growth and eruptive forces, which reflect her interest in natural cycles as part of the universe’s wider spiritual system.

LATER YEARS

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Colquhoun balanced her artistic output with her literary career, publishing books including The Crying of the Wind: Ireland (1955), The Living Stones: Cornwall (1957), Goose of Hermogenes (1961) and Sword of Wisdom (1975). She still exhibited her drawings and paintings regularly in Cornwall, London and internationally, and also joined several occult societies. She adopted the magical name Splendidor Vitro (‘More Sparkling than Crystal’), which she developed into a symbol used to sign her artworks.

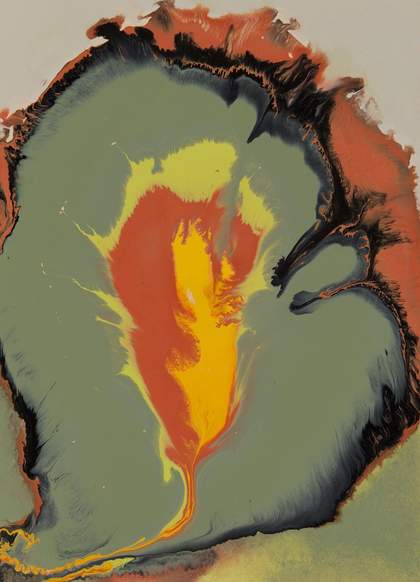

From the mid-1960s, Colquhoun often used an automatic process of dripping enamel paint to make ‘convulsive landscapes’. This concept was derived from André Breton’s earlier notion of ‘convulsive beauty’, which captured the blend of attraction and repulsion underlying much of surrealist art. The resulting works often show volcanoes, which in alchemy symbolise magical transformation. In the late-1970s, she used the same dripped enamel technique for her visionary tarot deck and The Decad of Intelligence, a book of paintings inspired by the Jewish Kabbalah. These abstract spiritual aids represent perhaps her most complete fusion of artistic and magical practice.

Ithell Colquhoun died in 1988 aged 81 of heart failure at the Menwinnion Country House Hotel, Lamorna. She bequeathed the contents of her studio to the National Trust and her occult works to Tate. In 2019, the majority of her works and archive materials were transferred to Tate, bringing together the world’s largest collection of this visionary artist, writer and occultist.

Ithell Colquhoun Volcano Fire, 1978. Tate Archive © Tate

TARO

In 1977, Colquhoun produced designs for a set of tarot cards, directly merging her artistic and magical practices. Tarot decks are typically used for fortune-telling or in games. They mostly include 78 cards split into the Major Arcana (trumps) and Minor Arcana (four suits), as with Colquhoun’s. She rejected the common spelling ‘Tarot’, believing ‘Taro’ was a truer reflection of its supposed Egyptian origins.

Colquhoun’s cards were made in response to the widely-used Rider Waite Smith pack. This was illustrated by artist and theatre designer Pamela Colman Smith, who used pictorial storytelling to interpret the cards’ mystical meanings. Colquhoun’s deck avoided figuration and narrative, instead using dripped enamel paint to create abstract compositions that were a significant evolution from the magical symbolism of her earlier works. They combine the spontaneity of surrealist automatism with colour theories and techniques promoted by the Golden Dawn, as well as ideas from the Kabbalistic Tree of Life.

Rather than providing direct instruction, Colquhoun’s deck was designed as a meditative tool which functioned as a visionary gateway to enlightenment. She exhibited it at the Newlyn Art Gallery in 1977, demonstrating her desire for it to be used widely as a spiritual aid. There the cards were presented as here, with the Major Arcana alongside the four suits representing the colour associations attributed by Colquhoun: yellow swords, blue cups, scarlet wands and indigo disks.

Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds at Tate St Ives 2025. Installation View © Tate Photography (Lucy Green)

Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds at Tate St Ives 2025. Installation View © Tate Photography (Lucy Green)

Ithell Colquhoun: Between Worlds at Tate St Ives 2025. Installation View © Tate Photography (Lucy Green)