Pop Art serves to remind us … that we have fashioned for ourselves a world of artefacts and images that are intended not to train perception or awareness but to insist that we merge with them as the primitive man merges with his environment. The world of modern advertising is a magical environment constructed to produce effects for the total economy but not designed to increase human awareness … Pop Art is the product of drawing attention to some object in our own daily environment as if it were anti-environmental.

Marshall McLuhan, ‘The Relation of Environment to Anti-Environment’1

It is difficult to exaggerate the invasion of commercial brands, billboards, photographs, magazines and packaging designs that overwhelmed culture beginning in the 1960s. Advertising and its viral propagation on the street, in the home, through print and celluloid, presented an unprecedented aesthetic challenge, marked by its proliferation around the world. If consumer culture was branded quintessentially American, it was in fact indelibly global. While Marcel Duchamp had responded to the explosive production of materiality in the latter stages of the industrial revolution with the readymade, the next generation of artists had to contend with not just the object but a whole environment. Pop art, we know, was an inevitable rejoinder to the flow and dissemination of images of products (as much as the objects themselves). These images were no longer created after reality, but after icons pre-coded by the media.

Ever prescient, Marshall McLuhan identified in 1966 how pop, in contrast to the ‘disinterest’ expressed by Duchamp’s readymade, contended directly with the product or image and expressed an active interest in breaking through its passive consumer landscape, advertising attention to that very place from which it was born. Post-readymade, but pre-simulacra, pop was still concrete. It built its desired socio-economic and commercial meaning into the figuration of the object in a manner reminiscent of Roland Barthes’s famous formulation, in Mythologies (1957), of the sign that flickers between signifier and signified, so that the image or text, icon or logo denotes a real object but also stands as a simultaneous representation of a code. Whether that code was complicit or critical has been the story of pop art’s reception and, in particular, that of its first generation of US-based artists. But that very question meant different things in different contexts.

Thus far, the history of pop has reaffirmed the notion of its dissemination from founding hubs in New York and London to other parts of the world. Arriving in the wake of a socially and politically revised global landscape that placed the USA in a central position, pop was of course irrevocably associated with the emerging dominance of America. Due largely to its commercial appeal and success, pop’s narrative was subject to a forceful, gallery-driven marketing that resulted in narrow parameters being set from its first appearance, and the consequent exclusion of numerous, mostly female, artists from entering the arena in the USA.2 Simultaneously, a (largely New York-based) pop history was being written in John Rublowsky’s Pop Art (1965), Mario Amaya’s Pop as Art (1966) and Lucy Lippard’s Pop Art (1966), and through dealers such as Leo Castelli and curators such as Lawrence Alloway. This was a process that edited out alternative pops – and pop in other places – before they were even understood to exist. Indeed, this process of exclusion can be read as a direct or deliberate echo of the convergence of critics, market and exhibitions that established abstract expressionism as the dominant art movement in the post-war USA.

Yet around the world, ‘pop’ did not just signify North American popular culture. Pop arose in singular forms and designations, but in no singular lineage. Many pops emerged simultaneously, and often imbued with an ambivalence, if not outright hostility, to the notion of American economic (and implicitly artistic) dominance. While television, newspapers and magazines proved efficient conduits for transmitting the product of American culture globally, US-branded advertising was still largely absent in many regions of the world where such goods were not imported at all, or were too expensive. Instead, regional pop and film stars, local fashion houses and car manufacturers were dominant, and other home-grown visual messaging such as street signage, comics, banners and posters provided alternative inspiration and platforms for pop activity. This was global yet specific pop.

What do we talk about when we talk about pop? For one, pop style or a pop spirit encompassed graphic techniques that mimicked popular, commercial and media art, with flattened, simplified and cut away imagery, bright artificial colours, and the combination of text with image. Achieved through projecting an image onto a flat surface and tracing it, or through various types of printing processes – although serigraphy was not always available – the resulting abridged figuration also drew from street signs a universal and yet localised language. Mass media, desire, culture: the most iconic terms associated with pop art must be reconsidered in its global contexts, where ‘the masses’ and ‘culture’ had no single hegemonic definition.

Many pop artists, not just in the USA but all over the world, emerged from a design background, and the convergence in pop of graphics, design, architecture and art is a direct result of this crossover. The emerging force of media – television, photojournalism and a new culture of ‘breaking news’ – drew pop artists to bold forms used for laconic effect: re-appropriating (in many instances illicitly) the plates or moulds from printing presses and the photography commissioned for journalism. In locations where censorship was editorial policy, artists were acutely aware of the potential in disrupting intended meaning. The desire for an immediacy of impact was often directed towards political rather than profitable ends in global pop, where serial imagery and duplication became central for the production of an easily distributable mass art form comparable to popular printmaking (operating outside of a commercial context) rather than limited to a commentary on commercial practices.3 Pop style also appropriated the advertised object itself through sculpture, often made with new consumer materials: inflatables, malleable soft sculptures and brightly coloured plastics, which offered human associations tinged with the sinister threat of the unnatural, or even, in the omnipresent shadow of war, dismemberment.

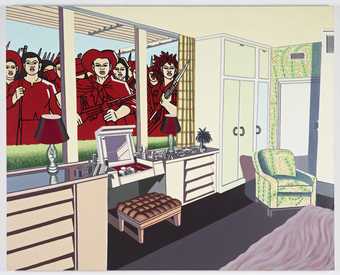

Fig 1.

Erró

American Interior No.1 1968

Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015

Just as ‘pop style’ encompasses various strategies of composition and process, so there is not one universal pop art but rather hundreds of iterations around the globe that share a populist concern. Numerous artists and movements with a pop strategy developed, including nouveau réalisme, neo-dada, Otra and Nueva Figuración, Saqqakhaneh or Spiritual Pop, and Equipo Crónica, as well as such singular figures as Öyvind Fahlström, Keiichi Tanaami and Erró. These tendencies differed from one another due to their origins in countries as various as Argentina, Brazil, France, Iceland, Japan, Peru, Poland and Spain, and were necessarily informed by their respective traditions and socio-political situations. Countering the mainstream impression that pop art operated as a simple adaptation of the techniques and images of consumer culture, global pop mined the media as a critical, material source for artists investigating the effects of everyday culture. Pop – and this can of course also be said of the more ambivalent work of Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol too – was rarely just an affirmative aestheticisation of commodity culture or consumer behaviour but employed the language of advertisements and marketing, the language of the magical commercial environment as identified by McLuhan, to turn established communication strategies into political opposition, satiric critique, subversive appropriation, and utopic explorations of collective and individual identity. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the multiple global permutations of pop. Tactics of pop appropriation could be made to have completely different meanings. Anti-imperialist critique clothed itself in the signifiers of dominant commercial ideology in order to outstrip it, while situating itself firmly and joyously within contemporary culture.

Given that global pop was largely a response to diverse strains of local and international commercial media rather than specifically American pop art, and reflected a desire to create a truly populist art form, it is unsurprising that its many manifestations, even in adjacent countries, could be developed in relative isolation. Despite this lack of transnational communication or dissemination, shared themes and concerns can be observed across the globe, indicative of contemporary socio-economic realities, but also an understanding of the operations of mass media itself. In particular ways, pop iterations throughout the world deformed, extended or inverted certain strategies of American pop, and developed tactics wholly different from American pop, in dialogue with specifically vernacular consumer environments.

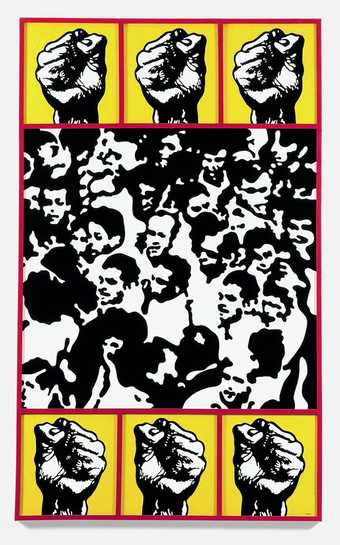

Fig.2

Claudio Tozzi

Multitude 1968

Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo, Brasil

© Claudio Tozzi

What became of subject formation under this advertising invasion, particularly as the individual was both mass media’s prize possession and its victim? While pop’s canon replicated the image of the isolated consumer, reinforcing the hyper-individualisation under capitalism that burgeoned in the second half of the twentieth century, global pop artists brought the crowd crashing back into the living room, bursting from the contained safety of the television screen and disrupting the hygienic atmosphere of the singular figure or discreet shopper. Think of Erró’s American Interiors from 1968 (fig.1), with its globally diverse crowd of proletarians, culled from socialist realist Chinese artwork, who appear to be invading with intent bourgeois interiors collaged from a household magazine. The demonstration or crowd provided fertile terrain for a miscellaneous group of artists and artists’ collectives who recognised and hijacked the image of the masses, which stood for, on the one hand, the hidden populace that made possible the consumer society being sold through an apparently subjective, individual appeal, and on the other, an assembled, and on occasion underground, political opposition to the status quo. Within the graphic arts – arguably one of the most media-appropriate realms for pop – ‘pop’-style was marshalled productively for political posters from the Situationists to the Black Panthers, Sister Corita and the Viet Cong. Representations of mass events – Claudio Tozzi’s Multitude 1968 (fig.2), Gérard Fromanger’s Album The Red 1968–70, Henri Cueco’s The Red Men, bas-relief 1969, and Equipo Crónica’s Concentration or Quantity becomes Quality 1966 – reassert collective action and communality, in opposition to such remote pop icons as Marilyn or Elvis, based on publicity stills. Whether left-leaning graphic poster production (including the work of Paris-based New Figuration artists for the 1968 protests) or artist-designed flags for the demonstrations in São Paulo and Rio that same year (made by Nelson Leirner, Tozzi, Rubens Gerchman, Carmela Gross, Hélio Oiticica and Antonio Manuel among others), collaborative, public production aimed to bring pop-influenced work into the realm of art made for mass consumption, if not agitation. Global pop represented and framed the crowd, while also orchestrating and unifying it.

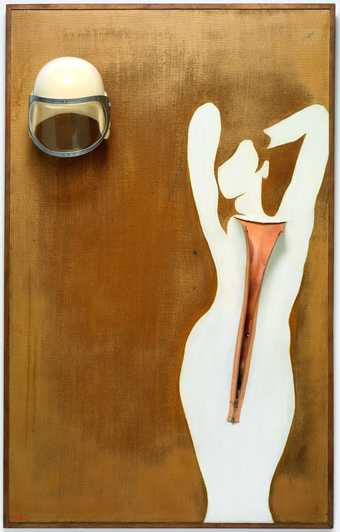

Fig.3

Evelyne Axell

Valentine 1966

Private collection

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015

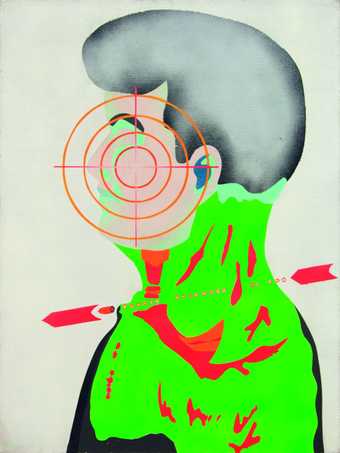

At the same time, global pop was also instrumental in representing individual subjectivity, even if only to emphasise its erosion and loss under tabloid conditions. Just as in Warhol’s work, this led to image manipulations that denote celebrity or popularity, but also the traces of defamation that linger even in the most apparently elevated portrait.4 For example, Raúl Martínez’s numerous laudatory images of Fidel Castro (Listen America c. 1967) and Evelyne Axell’s portrait of the astronaut Valentina Tereshkova (fig.3), the ambiguous portrait of Robert Kennedy by Joav BarEl (fig.4), and Dušan Otaševíc’s portrait of General Tito, which was intended as a congratulatory laudation but was severely received by the Communist party of Yugoslavia as an unauthorised portrait of the leader.5 We see the illicit instrumentalising of pop’s effect by Cornel Brudaşcu in his portraits of friends and artists in Cluj, Romania, whose visages are transposed onto the appropriated pop bodies of figures that the artist extracted from imported Western magazines featuring album covers by bands such as The Doors. Understanding the elevating effect of the brightly coloured airbrushed effect but knowing nothing of the music or context for this pop culture, Brudaşcu manipulated the icon-effect to celebrate friends such as a recently deceased fellow artist in Guitarist 1970.

Fig.4

Joav BarEl

Kennedy Assassination 1968

© Joav BarEl Estate and Tempo Rubato, Tel Aviv

Elsewhere, artists deployed a kind of ironic mimicry in order to address the forms of mass media as a specifically imperialist, capitalist, foreign structure. Take, for instance, Öyvind Fahlström’s Mao-Hope March 1966, a fake demonstration humorously and irrationally linking Bob Hope (the comedic star of US film and television) with the Chairman of the Communist Party of China (leader of the ‘Long March’, whose image reproduction and distribution outdid any Hollywood star or corporate logo). Recorded as a faux-documentary in which participants/demonstrators answer questions in a manner directly recalling the recent and ongoing civil rights marches or the demonstrations orchestrated against the Vietnam War, Fahlström’s work reshoots the latest televisual motifs and vacuous vox populi commentary for a distinctly non-didactic, anarchic critique of news-lite coverage. Similarly, in Eastern Europe, the delayed arrival of consumer culture was highly fraught, and met with suspicion as both a ‘liberator’ from and similar continuation of older systems of mass information as disseminated by the state. Poland’s relatively open economy (especially after 1972) allowed for greater access to foreign goods and exposure to advertising, both of which are critically deconstructed in such works as the film Rewizja Osobista Personal Search (1972) by Witold Leszczynski and Adrjez Kostenko. Actual advertisements are collaged into a story of a family’s failed attempt to import European goods to Poland from Switzerland; the absurdity of the aspirational fantasy – symbolised throughout the film by a mountain of packaging with its accompanying labels and logos – is set in contrast to the final moments in which the border guard and the matriarch of the family revert to nostalgic recollections of their youthful political commitment while the teenage son sets fire to the (imported) Fiat car and its contents in a conflagration of melting products. Natalia LL’s Consumer Art of 1972, 1974, 1975 similarly suggests a withering send-up of the excesses of sexualised marketing: her best known work in the series is a video in which a model provocatively consumes a banana (itself a rare import in Poland in the 1970s).

Earth was not pop’s only frontier: space exploration from the late 1950s brought the possibility and fantasy of new utopias. Interest was not confined to those countries with space programmes. The world was drawn along ideological lines: Sputnik versus Armstrong. The Cold War space race, the presence of female astronauts beginning in the 1960s, the notion of a territory un-bounded by the strictures of daily life, and a fascination with cutting edge technology and materials, resulted in a profusion of pop art around the planet that utilised the metaphors of space travel to explore novel realms of national and personal identity. Sculpture materialised these interests in aggressive, alien, robot-weaponry, among them the massive-scaled Machine No.7 1967–8 by Shinkichi Tajiri, constructed from steel, Plexiglas and aluminium, which made evident the underlying tensions – erotic, military and technological – within competitive space exploration. Taking a different perspective, numerous women artists, attracted by the lure of a radically equal society and by the androgynous clothing – helmets and space suits – explored space imagery within their pop works. Austrian Kiki Kogelnik frequently depicted herself and others in flat outline falling through space, and Nicola L devised oversized space costumes as sexless soft sculptures, both also offering an alternative to the hyper-sexualised female space traveller Barbarella in the comics of J.C. Forest and the subsequent eponymous 1968 film by Roger Vadim.

Fig.5

Delia Cancela

Broken Heart 1964

Private collection

© Delia Cancela

If space travel offered the body a weightless, genderless existence, artists also explored its abject potential, wrested free from advertising’s airbrush. The body in parts, dismembered and disembowelled, is a recurring motif among women artists’ work, such as Anna Maria Maiolino’s Glu Glu Glu 1966, a soft sculptural relief of the featureless (with the exception of the mouth) upper body and digestive organs using a bright pop palette, and Delia Cancela’s painting Broken Heart 1964 (fig.5), in which missing parts cut from a heart hang suspended below the canvas. For artists of both genders, the pronounced representation of desire was often commingled with political radicality, as well as an uncertainty with regard to the outcome of the seismic changes taking place in the gendered social order. Antonio Dias’s remarkable works, for example Note on the Unforeseen Death 1965, bring together soft sculptural relief elements that combine erotic impulses with a dark militaristic imagery, the environmental painting-sculpture of Wesley Duke Lee’s Trapeze or a Confession 1966 suggests both a male celebration of liberated female sexuality and the conflicting desire for a coexistence of traditional domestic life.

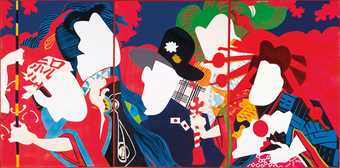

Fig.6

[ORIGINAL_CAPTION]

While lowbrow culture provided global pop with its most direct and obvious source, art’s own image archive was prime material for recoding history to the contemporary moment. ‘Pop-ing’ art history was a comparatively rarefied if resonant gesture around the world. Parroting the conservative criticism that pop style was superficial and commercial, artists used pop to debase or de-throne the artistic hierarchy or heritage from which they had emerged. Equipo Crónica, a group formed in Spain in 1964 by Manolo Valdés, Rafael Solbes and Juan Antonio Toledo, made frequent use of Pablo Picasso as a national myth, in particular applying a pop style to works such as Guernica 1937. The artists’ work of the same title from 1971 features a close-cropped image of the famous horse from Picasso’s mural exploded by Lichtenstein’s eponymous Whaam!. Equipo Crónica’s work politicises Picasso through its ambiguous connection to American popular culture’s iteration of violence while suggesting the ideological critique of the ‘cultura de la evasion’ that existed during Francisco Franco’s regime. Their collective stance was staked out in opposition to the notion of the individual genius or artwork; indeed, many of their works point to the ricocheting connections and dependencies between generations of artists. Elsewhere, both national and foreign heritage was also called into question. In Japan, Ushio Shinohara, following the visit to Japan of Robert Rauschenberg, began his Imitation Art series producing multiple duplicates of the artist’s Coca-Cola Plan 1958, and thereby mass-producing the handmade pop of Rauschenberg. Shinohara’s later Oiran series (including Doll Festival 1966 [fig.6]) was based on images of geishas from Edo-period woodblock prints. These fluorescent pop works used plastics as well as paint (flat cut-out figures against empty backgrounds) and transformed traditional prints into garish, faceless travesties of taste.

Pop’s criticality was often misconstrued as it was first developing, and the critique employed by its many artists seen as positively embracing US-influenced commercial media or indeed as an all too simplistic détournement. This is particularly true of women pop artists, who withstood the double exclusion of the movement’s almost exclusively male terrain and a rejection by other women artists for working in a mode that appeared contrary to feminism’s concerns.6 The dialectic of pop – its immersion into a commodified environment while at the same time providing a language of mass appeal with which to critique and negate it – was felt by contemporary observers to be complicit with dominant power structures, despite that very dialectic. It is true, of course, that pop art, even in its most politically utopic iterations, was necessarily cannibalistic, a kind of ouroboros, feeding off and destroying itself. Pop carried within it what Jürgen Habermas called a ‘performative contradiction’ (which, ironically, he also observed in the Frankfurt School critique of the culture industry): that the denunciation of an ideology employs in its critique the very language of that ideological power. For pop, this meant a dissolution of its own language and ethos within the banality of the everyday, an environment from which it could not always extract itself to mount a sustained critique. The negative conundrum implicit in this performative contradiction was turned into a methodological opportunity in global pop, to simultaneously champion populist expressions and disavow the media’s ideological coinage.

While the past few decades have witnessed a thorough re-examination of the role of global conceptual art, and a history of post-war abstraction beyond the parameters of the USA and Europe, pop’s intentionally equivocal position internationally has largely been passed over and dismissed as an (often belated) artistic influence rather than as a complex, ambiguous and self-reflexive response to contemporary culture. Pop’s compound relationship to conceptual practice must be mapped more definitively, as we gradually free ourselves from the convenient monikers that have proved to be ready accomplices in a linear continuum of Western art history.

As exhibitions on pop at the Fundación Proa in Buenos Aires and the Museum Het Valkhov in Belgium, as well as the solo exhibitions of work by Axell and Kogelnik demonstrate, any effort now to redress history’s imbalance of global pop coverage necessarily has to first perform acts of retrieval, followed by a consequent process of remapping its definition and potential. McLuhan’s argument in 1966, ascribing to pop the capacity to act as an ‘anti-environment’ and provide a critical enquiry into the image saturation of twentieth-century life, attains further relevance in a contemporary moment in which this condition has increased a hundredfold. While conceptual art’s ongoing significance is widely accepted, pop’s varied past, particularly outside of the Western canon, needs to be reassessed and its meaning as an agitator and disassembler recognised. We should, in other words, pay attention to what pop in its global context brings to our attention.