Born 1940 in Belgrade, Serbia (former Yugoslavia), where he lives and works.

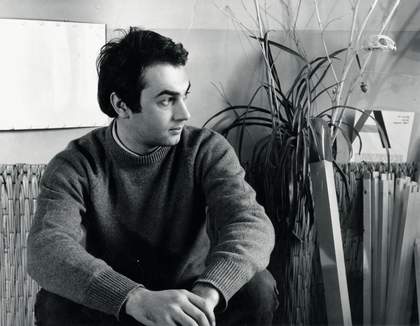

Dušan Otašević in 1967

Courtesy the artist

Dušan Otašević graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade in 1966. In the same year his work was included in the exhibition New Figuration of the Belgrade Circle at the Cultural Centre Gallery. While still a student, he turned away from the lyrical abstraction and tonal painting taught at the academy, instead finding his inspiration in Belgrade’s everyday life and in the popular culture of the rapidly developing ‘utopian consumerism’ in the country. Given Yugoslavia’s turn to the West, a unique hybrid of Western-style consumerism and socialist self-management – the Yugoslav ‘socialism with a human face’ – emerged. Keen to shed the romantic myth of the artist, Otašević chose to refer to himself as a craftsman rather than a painter or sculptor, using non-art tools and materials such as wood, glue, a chisel and industrial paint. Like many Western pop artists, he addressed consumer culture by appropriating its signs and visual language in his sculptural objects. Sharing much with American pop in his aesthetics and methods, in particular the oversized objects of Claes Oldenburg, Robert Indiana’s signs, and Warhol’s ‘before and after’ images, Otašević’s turn to the vernacular looked to comic strips and advertisements, traffic signs as well as hand-painted artisan shop signs. His ironic and humorous quotations often depict mundane processes and actions – such as smoking, eating and cutting – often shown in several stages, in comic-book-like frames with white backgrounds.

Frequently referring to the political situation in Yugoslavia, Dušan Otašević’s controversial work Comrade Tito, White Violet, Our Youth Loves You 1969, named after a patriotic song expressing the people’s love of the Yugoslav leader, depicts Tito as a pop icon – an act perceived as dissident given that any unofficial representation of the leader would automatically be read as a critique of the system. Towards Communism on Lenin’s Course 1967, a work made as a result of a student trip to Moscow, similarly reflects on Yugoslavia’s 1948 split from the USSR. The triptych shows the socialist red star, part of the Yugoslav flag, an image of Lenin and a traffic sign forbidding a right turn.

Lina Džuverović

September 2015