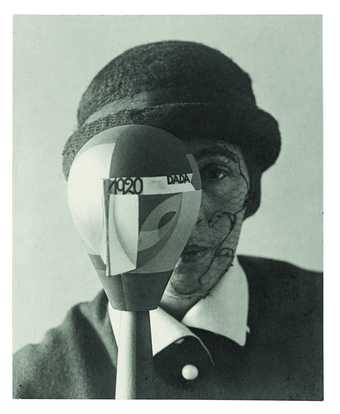

Nic Aluf Sophie Taeuber with her Dada Head 1920 Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin

Introduction

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943) was a crafts professional, teacher, architect, interior designer, painter, sculptor, performer, jewellery-maker and editor of an international art magazine.

Working first in Switzerland, then France, she developed her distinctive visual style during the First World War. Her practice continually challenged the boundaries between art and design. Unlike other modernist artists of the time, whose path to abstraction came through the breaking down of figurative forms, Taeuber-Arp worked from the geometric grid structures of textile. The colours and forms of crafts and textile making, as well as dance, continued to inspire her throughout her life. Through her engagement with crafts, design, graphic arts and exhibitions, Taeuber-Arp expressed her commitment to abstraction as an aesthetic model suited to everyday life. This can be traced from her crafts projects of the 1910s, through the architectural commissions of the 1920s, to her paintings in the 1930s.

Taeuber-Arp always stood apart from other modernist artists. Combining a successful crafts practice with boldly experimental painting, her work challenges the historically constructed boundaries separating art, craft and design.

Zurich - First World War

Sophie Taeuber was born in 1889 in Davos, Switzerland. She studied in Switzerland and Germany at schools that emphasised the interrelationship of fine art, craft and design. She took classes in drawing, design, woodwork and textiles.

At the outbreak of the First World War (1914–18), Taeuber moved to Zurich. She taught at the Trade School and established herself as a commercially successful crafts professional, resolving to ‘make the things we own more beautiful.’ She also enrolled at Rudolf von Laban’s School of the Art of Movement, one of the early centres for modern, expressive dance.

Switzerland remained neutral during the war. Artists, writers and thinkers from across Europe who wanted to escape from the conflict settled in Zurich. Among them was fellow artist Hans (Jean) Arp, who would become Taeuber’s lifelong partner. They married in 1922, after which she took the name Sophie Taeuber-Arp.

Throughout the war years Taeuber was developing her own non-figurative artistic language. She produced a series of vertical-horizontal compositions as both works on paper and cross-stitching embroideries. While other artists reached abstraction through a gradual process of breaking down and simplifying figurative forms, Taeuber drew directly on the grid structures of textiles.

Dada

The influx of artists and performers fleeing the war made Zurich a centre for the avant-garde. One of the most radical movements to emerge as a result was dada. This group of artists, poets and performers challenged the rationalism and social conventions that they believed had led to the war. Taeuber joined the group, embracing dada’s absurdist, playful, radical practices. She was a pupil of, and friends with, the leading contemporary dancers Mary Wigman and Katja Wulff. A single photograph from the time shows her performance at the opening of Galerie Dada in 1917, dancing to Hugo Ball’s sound poems in an avant-garde costume and mask. Ball called it ‘a dance full of flashes and edges, full of dazzling light and penetrating intensity.’

When Tristan Tzara invited Taeuber to submit a photograph for Dadaglobe, an anthology of the dada movement in 1920, she chose to appear with her Dada Head. This was a sculpture made using traditional woodturning technique. The carefully staged photograph presents Taeuber as an artist who challenged the established hierarchy of fine art.

In 1918, Taeuber was commissioned to make a series of marionettes for an adaptation of Carlo Gozzi’s 18th-century play King Stag. The project uniquely combined her interest in performance, her understanding of body movement aesthetics and her practical experience with woodworking.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp Angela (marionette for King Stag) 1918 Museum für Gestaltung, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Zurich. Decorative Arts Collection

Applied Art

As a student at the von Debschitz school in Munich in 1911, Taeuber told her sister: ‘furnishing rooms for an architect – wallpaper, rugs, upholstery, curtains and lamps, and perhaps even designing furniture – is what appeals to me most.’

This use of artistic principles to design practical objects, furnishings and fashion is known as applied art. Taeuber taught at the Applied Arts Department of Zurich’s Trade School for 13 years. In her 1922 publication, Remarks on Instruction in Ornamental Design, the artist argued that objects should have ‘a simple and functional form’.

Taeuber’s own output included cushion embroideries, beaded jewellery and accessories, as well as designs for rugs and textiles. Rejecting the idea that applied art was less important than fine arts such as painting, she signed some of her textile works, the beaded bag and a Dada Head with the initials ‘sht’ for Sophie Henriette Taeuber.

The first exhibitions of her work were within a crafts context. They were displayed at the museums of applied art and with the Swiss Werkbund, an association of artists, architects and designers. From 1918 she showed her works with the New Life association, which aimed to integrate abstract art into everyday life. Here her beaded necklace was shown alongside her turned-wood object. Similar works appeared in modernist publications such as Der Zeltweg magazine (1919) and El Lissitzky and Arp’s The Isms of Art (1925).

Strasbourg - Abstraction in Three Dimensions

After the war Taeuber-Arp travelled around Europe. Her photographs reveal a growing interest in architecture. As other international artists gradually left Zurich, Taeuber-Arp also considered working outside of Switzerland.

In 1926, she and Arp were invited to redesign a wing of the Aubette building in Strasbourg as a modernist entertainment complex. Given the scale of the project, they asked the Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg to join them. Taeuber-Arp took sole charge of the design concept for the Five o’Clock Tea Room, the Aubette Bar and the Foyer Bar, while collaborating with Arp and van Doesburg on other elements. The dynamic abstract environments she created immersed the viewer in geometric shapes and vibrant colour. Her work on the Aubette brought her international acclaim.

From 1926 to 1928, Taeuber-Arp took on various interior design projects for private homes and at the Hôtel Hannong. Collector André Horn commissioned Taeuber-Arp to design stained glass windows for his apartment. Here she combined traditional techniques with her modernist vertical-horizontal compositions.

Taeuber-Arp and Arp were granted French citizenship in 1926. For the next three years, however, Taeuber-Arp commuted from Strasbourg to Zurich, where she continued to teach.

Clamart - In the Artist's Studio

Taeuber-Arp’s success with the Aubette commission enabled her to buy a plot of land in the town of Clamart, near Paris. She designed a house for herself and Arp, which combined living quarters with studio spaces. It was her first architectural project, demonstrating her continuing dedication to practicality and functional detail.

In 1929, the artists moved into the studio-house, which became a mixing ground for the couple’s different artistic circles. Taeuber-Arp was closely involved with international abstract and constructivist artists, and occasionally exhibited with the surrealists.

In the years following her move to Clamart, Taeuber-Arp worked on furniture and interior design commissions. Her business card advertised her as an architect. The furniture she created for the studio-house uses a modular approach with interchangeable parts, showing a similar economy of form to her applied art work.

Parisian Abstraction

Living in Clamart brought Taeuber-Arp closer to the Paris art scene. She joined the abstract artists’ group Cercle et Carré and took part in exhibitions alongside Franciska Clausen, Sonia Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, Le Corbusier and Piet Mondrian.

In Strasbourg in the late 1920s, Taeuber-Arp had worked on paintings inspired by the Aubette. Briefly venturing into figuration, Café showed the crowd at a restaurant. In Paris, this shifted into a top-down perspective for the non-figurative Composition with Circles-with-Arms (1930). The circles and angular shapes became independent of one another in the series Animated Circles. In parallel, she adopted her modular approach to spatial paintings such as Six Spaces with Four Small Crosses (1932). Her abstract painting, like her dada projects, were characterised by playfulness, where improvisation was as important as structure and order.

Taeuber-Arp began to show her work internationally. She also exhibited in Paris with the Abstraction-Création group, founded in 1931. Through Arp, she continued to engage with surrealist artists while promoting broader approaches to abstraction, beyond geometric non-figuration.

Painting in Two and Three Dimensions

Visiting Munich in 1931, Taeuber-Arp witnessed the rise of the Nazi Party first hand. ‘These people are willingly narrowing their horizons and churning up a truly war-like atmosphere’, she wrote. ‘It was utterly depressing’. She took part in international exhibitions, venturing into graphic design and editorial work. Through these activities, she intensified her commitment to an open, broader creative practice through abstraction.

From the mid-1930s, Taeuber-Arp’s work began to move from modular structures towards freer organic forms. Her interest in form perceived through movement, resulted in a group of circular works. Drawing on her early experiments with woodturning, she created objects that challenged the division between applied art and sculpture. Some reliefs were illustrated and exhibited in a variety of positions, revealing the possibility of multiple perspectives.

Their dynamic qualities were noted by the abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky. He wrote of her reliefs, ‘To the beauty of the volume… is added the mysterious moving power of colour.’ Taeuber-Arp displayed these works at the 1937 Constructivists exhibition in Basel. Featuring 24 of her works, it was the largest display of her studio practice in her lifetime.

Second World War - The Artist in Exile

In June 1940, German troops entered Paris. Taeuber-Arp and Arp left their home in Clamart, seeking refuge in the unoccupied South of France. Moving frequently, staying with friends and lacking necessary equipment, Taeuber-Arp could only work with light, portable materials – often just paper and coloured pencils.

Many of the works created in 1940–42, foreground the importance of line to Taeuber-Arp. She experimented with monochromatic curving lines and compositions animated by planes of colour. These meandering lines evoke the continual movement and uncertainty that defined this period in Taeuber-Arp’s life.

Just before the outbreak of the war and during her exile, Taeuber-Arp collaborated on artist books. With Arp, she published two volumes of poetry, Shells and Umbrellas (1939) and Poems without Names (1941). She contributed to a graphic portfolio assembled by Max Bill (1941) and one by Arp, Sonia Delaunay, Alberto Magnelli and herself (1942/50).

Taeuber-Arp and Arp were granted visas to travel to Switzerland in 1942, where they stayed with family and friends. On the night of 14 January 1943, Taeuber-Arp passed away from accidental carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a faulty stove. She was 53. Taeuber-Arp was one of the most successful and innovative artists of her time.