Natalia Goncharova, Peasant Woman from Tula Province, 1910 State Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow, Russia) © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Room 1

The Countryside

Natalia Goncharova produced an astonishing variety of work, crossing the boundaries between art and design. Living first in Russia, then in France, she was a painter, print-maker, illustrator and fashion designer, as well as a set and costume designer for the Ballets Russes.

Goncharova was born in Russia in 1881. She grew up on her family’s country estates in Tula province, 200 miles from Moscow. Her family were impoverished aristocrats, who made their fortune through textiles. From early childhood, Goncharova witnessed the demands of the farmers’ lives – working the land, planting and harvesting. She was also familiar with all the stages of textile production, from shearing sheep to weaving, washing and decorating the fabric.

The first room in the exhibition includes a traditional costume from the region alongside paintings that show Goncharova’s identification with the people and culture of rural Russia. She often returned to the family estate. In her early years as an artist some of her most productive and inspired work was created there. Throughout her life she drew inspiration from the colours and stylised forms of traditional Russian arts and crafts. She collected and exhibited icons, popular prints and tray-paintings, and actively campaigned for the preservation of traditional art forms.

In Imperial Russia, social roles and behaviour were dictated by rigid class structures. Goncharova didn’t fit easily into the accepted categories. As an aristocrat’s daughter, a radical artist and a woman she always stood apart.

Room 2

Moscow

When Goncharova was eleven, her father moved the family to Moscow. At the age of twenty, she enrolled at the School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. It was here that she met fellow artist Mikhail Larionov, who would become her lifelong partner.

Early twentieth-century Moscow was one of the best places in the world to see modern European painting. Two industrialists – Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin – built up and displayed extensive art collections that included works by Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Pablo Picasso and André Derain. Their family collections started with Russian icons and included traditional arts and crafts, such as wood and stone carvings and popular prints. These works shared many of the characteristics of early modernist art, such as bold colours, minimal forms and flattened surfaces. Learning to appreciate these qualities helped Shchukin and Morozov to recognise the talent of avant-garde artists in both Europe and in Russia. Goncharova and Larionov were among the young Russian artists whose works were acquired for the Morozov collection.

Room 3

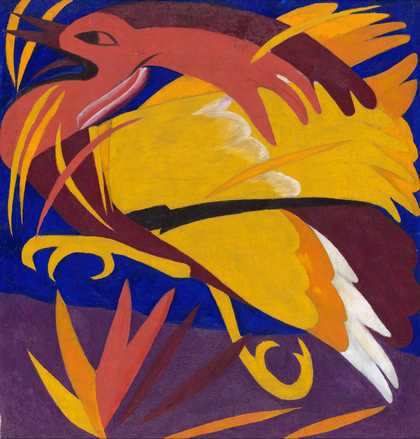

Natalia Goncharova Harvest: The Phoenix 1911 State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Bequeathed by A.K. Larionova-Tomilina, Paris 1989 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

1913 Exhibition

In September 1913 a vast retrospective of work by Goncharova opened at the Mikhailova Art Salon in Moscow. Including more than 800 works, it was the most ambitious exhibition by any Russian avant-garde artist to date. Goncharova was thirty-two years old.

The term ‘everythingism’ was coined by Larionov and the writer and artist Ilia Zdanevich to describe the diverse range of Goncharova’s work and her openness to multiple styles and sources. The exhibition included paintings, works on paper, designs for theatre, textiles and fashion, wallpaper and popular prints. There were early works that showed the influence of French impressionism as well as paintings inspired by Russian icons and folk art. Scenes of village life and rural landscapes appeared alongside depictions of the city. For the first time Goncharova could install large-scale works such as the nine-part Harvest.

Goncharova was thrilled by the response. In a letter she described ‘Bundles of newspapers featuring articles one contradicting another… There were public scandals and receptions in restaurants, three editions of the catalogue, commissions for portraits, for a carpet, for stage decors; and three works were purchased for the Tretyakov Gallery’.

Room 4

Natalia Goncharova Design with birds and flowers. Study for textile design 1925–8 State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Bequeathed by A.K. Larionova-Tomilina, Paris 1989 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Fashion

Photographs and personal accounts from those who met Goncharova testify to her unique approach to self-presentation. This included parading in the streets of Moscow with her face painted and wearing extravagant outfits. According to Sergei Diaghilev, the founder of the Ballets Russes, her style was imitated by bohemian society in Moscow: ‘It was she who made the shirt dress fashionable – black and white, blue and ginger’.

Capitalising on this reputation, the fashion designer Nadezhda Lamanova commissioned Goncharova to create designs for her Moscow-based fashion house. Goncharova worked on embroidery patterns and designed ornamental needlework and textiles, combining bold floral motifs with the striking colour palette seen in her paintings. A selection of designs was included in her 1913 exhibition.

Later in her career, when she was living in Paris, Goncharova collaborated with Marie Cuttoli, whose design house Myrbor showcased carpets and fashion designs by famous contemporary artists. The repeating floral motifs look back to the vibrant local costumes and printed textiles from her childhood in rural Russia.

Room 5

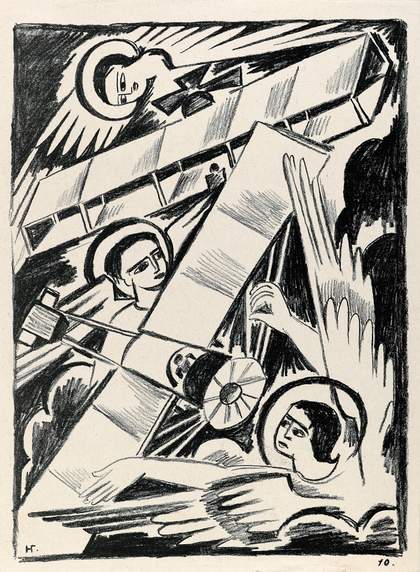

Natalia Goncharova Angels and Aeroplanes from Mystical Images of War 1914 Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Purchased 2004 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

War

In April 1914, Goncharova and Larionov arrived in Paris. They were invited by Diaghilev to work on designs for his opera-ballet Le Coq d’or (‘The Golden Cockerel’), which was performed to great acclaim in both Paris and London. The two artists then staged a joint exhibition in Paris. In August, however, the outbreak of the First World War forced them to return to Moscow. Larionov was called up for military service and sent to the front line. Within weeks he was wounded, hospitalised and later demobilised as not fit for combat.

Goncharova’s series Mystical Images of War was published in autumn 1914, picturing the war as both patriotic and catastrophic. The national symbols of the Allied Powers (Britain, France and Russia) are brought together with images from the Book of Revelation and Russian medieval verse. Blending contemporary warfare and ancient prophecy, Goncharova portrayed angels wrestling biplanes, the Virgin Mary mourning fallen soldiers, and the Pale Horse that Death rides in the Apocalypse.

This portfolio was Goncharova’s first series using lithography, a technique for printing using metal or stone. She hoped that producing a series of prints would enable her to distribute her work more widely.

Room 6

Natalia Goncharova, from The Evangelists 1911 The State Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Gift of A.K. Larionova-Tomilina, Paris 1966 © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Art and Religion

The tradition of devotional religious painting – the icon – is central to the development of Russian art. When Goncharova produced her own approach to religious imagery, she was knowingly engaging with the heart of Russian culture. She believed that contemporary artists could draw inspiration from the direct imagery and simplified forms of icons as well as from popular prints – known as luboks – which often included religious subject matter.

By reinterpreting icons in her own work, Goncharova entered challenging territory. For the devout, icon painting was an exclusively male practice. In 1912 the authorities had removed The Evangelists from a group show organised by Goncharova and Larionov on the grounds that an avant-garde exhibition was an inappropriate setting for sacred imagery. For her 1913 exhibition Goncharova placed her religious paintings in a separate room, and they were acknowledged as among the strongest works. When the exhibition reached St Petersburg, however, they were again removed by the censors.

Room 7

Natalia Goncharova in her flat, rue Jaques-Callot, Paris, late 1920s. State Tretyakov Gallery Manuscripts department

Artist Books and Prints

Before the First World War, Goncharova was at the centre of creative activity in Moscow. She exhibited in Russia and abroad, and took part in debates, gatherings, cabaret performances and films. Artist manifestos, exhibition catalogues and other printed materials were commonly used to promote radical ideas and publicise artworks. Goncharova and Larionov produced a number of artist’s books. They collaborated with the writer Aleksei Kruchenykh to design volumes of zaum (transrational) poetry, which brought together images and handwritten text.

In Paris, Goncharova continued her experiments with book illustration, using lithographs and stencil prints. She worked on poetry, fairy tales, and texts on contemporary theatre design and medieval Russian verse. In the 1920s Goncharova also took part in preparations for a series of artist balls. For these flamboyant theatrical events she designed posters, tickets and programmes, and devised masks and puppets.

Room 8

Modernism

Around 1912–13 Goncharova began to address more urban subjects in her work. She portrayed machines and factories, placing a new emphasis on movement. Like other avant-garde Russian artists, she was responding to Italian futurism – a call for artists to reject the past and celebrate the dynamism of the modern age – as well as the fractured perspectives associated with cubism. This combined style was known as cubo-futurism. For Goncharova, this was not an abrupt break with her early work: ‘The principle of movement is the same in the machine and in the living being’, she remarked. Larionov followed these developments by publishing two manifestos to promote rayonism (also known as rayism). The ‘rays’ that shape Goncharova’s paintings from this time capture real forms, providing ‘skimmed impressions’ of landscapes, plants or people.

Rayonism suggested a world beyond the visible. Goncharova’s depiction of energies such as electricity and rays that intersected solid objects led her towards abstraction. Goncharova was one of the first artists to embrace non-figurative art.

Room 9

Goncharova in Paris

Goncharova and Larionov left Russia in June 1915 to tour with Diaghliev’s Ballets Russes through Switzerland, Italy and Spain. But the October Revolution in 1917 and the five-year Civil War meant that they were unable to return to Moscow. In 1919, Goncharova moved into a flat in Paris that would remain her home for the rest of her life.

During these years Goncharova showed her work in Europe and the United States. She received commissions for fashion, costume and interior design. Having a studio enabled her to return to large-scale works. She became fascinated by Spain, whose colourful outfits and vibrant culture reminded her of Russia. The figure of the Spanish Woman appeared in her paintings, prints and advertisements until the late 1930s.

Goncharova’s activity as an art tutor brought her a number of North American students, who helped to introduce her work to overseas audiences. She made standing floor screens for various collectors and institutions, including the Arts Club of Chicago.

Room 10

Theatre

This room brings together Goncharova’s sketches, costumes and set designs from several ballet productions.

Goncharova worked alongside a gifted array of Russian composers, dancers and artists recruited by Diaghilev to work for the Ballets Russes. Together they manufactured an ‘exotic’ vision of the east for captivated audiences in the west. The Paris production of Le Coq d’or in 1914 brought Goncharova international fame. The costumes and designs shown here are taken from a 1937 production in London.

The religious drama Liturgy was an ambitious collaboration between Goncharova, the choreographer Léonide Massine and the composer Igor Stravinsky. The project was never realised but it became famous after Goncharova produced and distributed a number of prints based on her designs.

Les Noces (‘The Wedding’), a ballet by the choreographer Bronislava Nijinska with music by Stravinsky, opened in 1923. As with her other productions such as Sadko, Goncharova’s understanding of the technical challenges of designing for erforming artists was combined with an imagination rooted in the popular culture of Russia.

After Diaghilev’s death in 1929, Goncharova continued to design for other companies and solo performers until the late 1950s. Her designs for The Firebird were reconstructed for the 2019 performance at the Royal Opera House.

Though her last years were plagued by ill health, Goncharova was still making work and taking part in exhibitions. She passed away in Paris in 1962, aged eighty-one.