Lubaina Himid Six Tailors 2019 Rennie Collection, Vancouver © Lubaina Himid

Audiences as Performers

What is my plan

What will I learn about myself here

What would I do in this situation

How is my life the same as this one

What does this setting offer me today

Which questions am I asking

How fast do I want to go

Who do I want to be

What can I hear

What do I want to say

Who could I work with

What would a sharing of space mean

Can we do this together

What makes me happy

What am I frightened of

How much power can I have and what will I do with it

Where shall we go together

What does love sound like

What do I really want

Is this enough

How much time do I need

What difference can I make

What can an understanding of language do

Is this really what I want to do

How should it endLubaina Himid 2021

Introduction

The stage is set. None of us know exactly what happens next. The galleries before you are arranged with the hope you will find them useful – a stage for considering the personal and the political.

Lubaina Himid’s powerful and poetic work has made her an influential figure in contemporary art – from her pivotal role in the British Black arts movement of the 1980s to winning the Turner Prize in 2017. Throughout her career, Himid has explored and expanded the possibilities of painting and storytelling, drawing attention to invisible aspects of history and extraordinary moments of everyday life.

This exhibition reflects Himid’s interest in opera and her training in theatre design. Unfolding as a sequence of scenes we, the audience, are welcomed as active participants. She says:

The audience member is in the paintings … The experience should be similar to entering a room and deciding what you’re going to do, how you will react and interact.

Her work asks us questions. Flags hanging in the exhibition’s entrance are designed like East African Kanga fabrics which include phrases of wisdom and affirmation, expressed here through lines of poetry. Together, they are titled, How Do You Spell Change?

With a series of questions placed throughout the exhibition, Himid asks us to consider how the built environment, history, personal relationships and conflict shape our lives. In the leaflet, they are presented alongside texts by the curators, and quotes from the artist. Together, they are envisioned as starting points for conversation, for taking action, and for making changes.

[ENTER STAGE RIGHT]

We live in clothes, we live in buildings – do they fit us?

Installation view from the exhibition Lubaina Himid: Our Kisses are Petals, BALTIC Centre for Contempory Art, Gateshead, 2018 © Lubaina Himid

Himid’s work challenges the rigidity of the architectural structures we inhabit. She paints homes for women with curving walls that suggest movement and growth over time. Would our lives feel different if the built environment was tailored to our needs and desires?

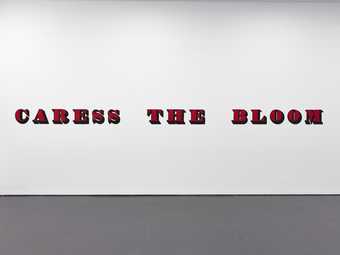

Walls come alive with messages, such as in Our Kisses are Petals, Our Tongues Caress the Bloom, wrapping around us like a textile as we enter the gallery. Metal Handkerchiefs, a series of nine vibrantly painted sheets of metal, reference the language of health and safety guides that dictate the ways in which buildings are constructed and used.

Himid’s questioning of structural rules and regulations reminds us that we ought to have agency to create and alter our own spaces. She invites us to consider what kinds of spaces could nurture our creativity, and what tools and materials we need to imagine and make freely.

What kind of buildings do women want to live and work in?

Has anyone ever asked us?

What are monuments for?

Lubaina Himid Jelly Mould Pavilions for Liverpool 2010 © Lubaina Himid

Lubaina Himid Jelly Mould Pavilions for Liverpool 2010 © Lubaina Himid

Jelly Mould Pavilions for Liverpool is an imagined architectural competition to design public monuments for the city. They commemorate the contributions of people of the African diaspora to Liverpool’s wealth, history and culture. Himid pretended that she had invited leading architects from all African nations to submit models. The submissions, made by Himid herself, repurpose Victorian jelly moulds as the architectural models.

Originally used to make decorative sweet treats, the ceramic moulds are often ornately shaped on the inside while their exteriors were kept plain. Her interventions reflect on the entanglement between the consumption of sugar, the transatlantic trade in captured Africans, and the economic development of British cities. They were displayed in 2010 in multiple locations across Liverpool, such as museums and shop front windows.

The Jelly Mould Pavilion project takes commemoration and cultural contribution as its themes and seeks to provoke debate about how a range of future shifts in the cultural landscape could accommodate the possibility of happiness. How can laughter and togetherness be depicted? … Can we devise strategies for an architecture of pleasure?

What does love sound like?

There is a physicality to sound that you may not see, but you may feel. Since the 1980s, Himid has produced sonic works that extend the theatricality and themes of her paintings. In recent years, she has worked closely with the artist Magda Stawarska-Beavan.

We felt like composers, you know. When we were running sound tests in the gallery it felt like Magda and I, with the museum team, had managed to weave together all of the sound ... So the whole exhibition is now a composition.

This exhibition includes five sound works:

Reduce the Time Spent Holding

In this work by Stawarska-Beavan, Himid recites from health and safety manuals, as rhythms of machines and tools convey intimate aspects of making

Blue Grid Test

Patterns from around the world are woven with memories related to the colour blue, spoken in three languages

Old Boat/New Money

Sounds of the sea and a creaking wooden ship flood from a wave-like sculpture

A Fashionable Marriage

In a room of cut-out figures, baroque and taarab music play periodically, suggesting divided and overlapping worldviews

Naming the Money

Himid narrates stories about the lives of 100 African slave/servants – their former free lives and their current positions in European households – attesting to Black creativity and presence across history

How do you distinguish safety from danger?

Deserted architectural spaces teeter on the edge of the sea. Images and texts speak of difficult migrations and possible moments of refuge. Sea and sky appear in familiar and unfamiliar patterns. Conjuring trick diagrams and shifting architectural perspectives show both inside and outside, the visible and invisible.

Himid produced a series called Plan B in the late 1990s, many of which present different depictions of water – both naturalistic and coded into pattern. Some panels include written narratives telling of exile and escaping conflict. The testimonies double and vary like musical refrains. Through the sea, memories, history and thoughts of displacement linger.

The ambiguity between safety and danger recurs in Himid’s work. The planks of Old Boat/New Money seem both precarious and sweeping. She says the cowrie shells painted on them represent currency and reference the beach, a site of both pleasure and trauma.

In reality, my method was to sit and ask: ‘What would it be like if this happened to me? How terrifying would this be … in a moving, stinking space, not knowing that it’s a wooden sailing ship, on this stuff that I don’t know is the sea?’ I try to work out how on earth I could actually survive as a human being if I ever got to the other side of the ocean … you’d hang on to those little talismans, if you could. Of course, that’s why the strategy is always to strip people of those things, but we still try to hang on and look forward.

What is the strategy?

Strategising and debates between women are frequently depicted in Himid’s paintings. As a tactic, Himid sometimes takes compositions from historic paintings and positions women in them as decision-makers who, she says, ‘are working out complicated futures together.’

In some paintings from the 1990s women are ripping up maps and navigation charts. They are seeking new, fairer methods of moving through landscape, life and conflict. Himid does not introduce resolutions. Rather, she leaves space in her artworks, around tables and places of gathering, for us to enter the scene and join the debate.

The women are always talking, sometimes to each other. The women do things together not always in the same way, but usually for the same reasons. The space they occupy is filled with them and expands with their ideas. They have several strategies, they expand to fit the situation. The women take revenge; their revenge is that they are still here they are still artists, that their creativity is still political and committed to change, to change for the good.

Scenery lift

Lubaina Himid A Fashionable Marriage 1984–6, partly reassembled 2017, 2021 (detail) © Lubaina Himid

We stand before a lift, usually used for transporting art objects into the gallery. Himid recasts this space as the backstage area of a theatrical performance.

She is known for her wooden painted cut-outs, particularly A Fashionable Marriage, first shown in 1986. The installation revises William Hogarth’s Marriage A-la-Mode: The Toilette – a satirical painting about the moral corruption of the elite in the 1700s. Himid adapts the scene to create a ‘furious caricature of the day’, focusing on the worlds of politics and art.

… in my reconstruction, one half of the room is all about the art world – the castrato is the critic, the flautist is the dealer, all these random people are artists … there’s the feminist artist, who’s the eager listener, listening to the critic, ignoring everything else, and being energised, if you like, by the young Black women artists.

The other half of the room is the political world of Margaret Thatcher, Reagan, the National Front, British fascists. And on the floor is a little girl who doesn’t do things in the same polite way as the Black woman artist… she’s saying to the artist: ‘Stop negotiating and being polite. We have to fight. We’re part of a big political battle.’

What happens next?

The work is not meant to comfort you or me, but it might sometimes remind us about what we already know, what might be useful to have remembered about the last crisis in order to avoid too much devastation in the midst of the next.

Himid’s paintings act as stages, inviting us into different worlds. She presents us with characters who are in the midst of difficult negotiations in their own lives. We are able to witness moments that are simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary, where cycles of tension from the past are still felt, where people are compelled to build and retain intimate relationships, despite the unknown.

A series of paintings called Le Rodeur features multiple figures in ambiguous interactions. The series is named after a French slave ship where, in 1819, a contagious illness caused blindness for nearly all who were aboard. The captain ordered 39 captured African men and women to be thrown overboard. Himid’s paintings do not show this history directly, but instead present us with unstable situations. She says we are seeing overlapping moments of past and present, and that some figures in the scene may be imagined by others.

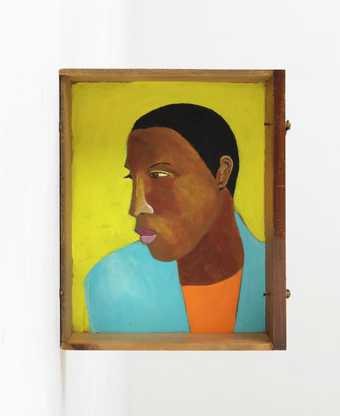

Many of Himid’s recent paintings show young men, well dressed and standing awkwardly with each other. They are in a moment of indecision, about to decide what to do next. Some figures are outlined in charcoal – the traces suggest they are in states of transition or on the verge of appearing.

I often refer to the men in these works as pastry chefs. This is to imply that they have worked all day to make something exquisite which someone else will admire and eat. The moment of the painting is at the end of the day, the moment of ‘in between’: the liminal time/space which could later be described as between now and then, today and tomorrow or a state of being alone and being together.

Lubaina Himid CBE RA

Man in A Shirt Drawer (2017–18)

Tate

© Lubaina Himid, courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London

Men in Drawers are portraits of men within furniture; their placement presents a sudden encounter through which the artist evokes ‘memories of people whose names no one had bothered to write down.’ Himid paints poetry and images on found objects, suggesting they are containers of history and memories. Old carts that were used to transport belongings and support livelihoods might help in an escape; they are painted with insects and animals that we often perceive as threatening.

Can we overcome our fears of the unfamiliar? Life is teeming around us. The carts themselves suggest a journey underway. How do you decide what to take with you?