How can we support our living worlds?

Gathering Ground explores threatened ecologies. It reflects on what cultivating relationships can look like when they are built on principles of equity. The exhibition brings together artistic practices that defend and embrace interconnectedness in our current ecological crisis.

Ecology refers to the relationships between living beings and their environments. It encompasses the delicate web of connections that sustain us all. Situated in the decommissioned oil and coal power station that is now Tate Modern, Gathering Ground offers a space to share the contradictions and tensions that arise when we think and act ecologically.

Looking at the ground on which we gather, the artworks ask:

How can we live with and make sense of destruction and loss?

How can we develop connections grounded in reciprocity?

What does it mean to be a good custodian for future worlds?

The artists’ practices are firmly grounded in land and place. Their works deal with issues such as displacement, alongside the destruction of waterways and land due to economic and military interests. Some honour Indigenous knowledges, while others highlight strategies for resistance in a precarious world.

At the heart of the exhibition is a year-long series of talks and workshops, including a new participatory commission by Abbas Zahedi. The programme invites visitors to explore these questions collectively. The shared discussions will form part of Tate’s research, reflecting on how to evolve as a sustainable and equitable museum in the 21st century.

CAROLINA CAYCEDO, YUMA, OR THE LAND OF FRIENDS II

GAURI GILL & RAJESH VANGAD, THE EYE IN THE SKY

Gauri Gill, Rajesh Vangad

The Eye in the Sky (2016)

Tate

The works in this room consider their environments as living beings. Carolina Caycedo, Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad highlight the experiences of land defenders and water guardians. They invite us to reflect on Indigenous knowledge and kinship with the land that are often lost through large-scale industrial developments.

Caycedo combines satellite images of the El Quimbo Dam in Colombia, during its construction, with aerial photographs and maps of the region before the dam was built. Repurposing images, typically used for military and extractive purposes, the artist resists exploitative ways of seeing and categorising land and waterways. In doing so, Caycedo creates a portrait of the land across time, drawing our attention to the impact that mega infrastructure projects have on river ecologies.

The dam’s construction displaced local communities, caused extensive environmental damage and redirected Yuma, Colombia’s largest river. Caycedo, who grew up by the river’s basin, explains: ‘I began to understand that the river is a political subject with agency to change the course of events and with a spirit and feeling that becomes an extension of the community that coexists with a river.’

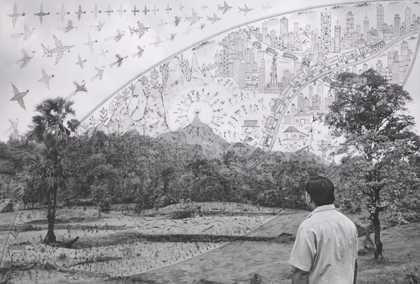

The collaborative work, The Eye in the Sky, shows Warli artist Vangad looking out over a revered mountain in the Dahanu area of the state of Maharashtra, in western India. This is a site sacred to the Warli, one of the many Indigenous Peoples in the Indian subcontinent (collectively known as Adivasi). Vangad added detailed drawings to the surface of the photograph – taken by Gill – including pictograms of birds and flying creatures, Warli gods and airplanes. He describes this as ‘the story of civilisation, the eye in the sky.’ The work depicts the Warli worldview of evolution across time, with the circle of gods and goddesses seated around the peak of the mountain, which forms the pupil of the eye.

Adivasi ways of life and of protecting the land are often at odds with extractive state and corporate powers. In this way, the work hints at surveillance and control. It foregrounds rich knowledge systems that are sometimes ignored today.

ABBAS AKHAVAN, STUDY FOR A MONUMENT

Made in the tradition of funerary monuments, the work commemorates plants instead of people.

Abbas Akhavan, 2022

Study for a Monument is an ongoing body of work that archives plant species native to the ancient region of Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in present-day Iraq. Decades of war and state intervention – such as the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88), the First Gulf War (1991) and the Invasion of Iraq (2003) – have had devastating consequences on the ecology of this area.

Akhavan has hand sculpted and enlarged each plant out of wax then cast them in bronze. The casts, resembling burnt fragments, are shown on white bed sheets on the ground. They recall pages from botanical studies, confiscated goods or objects laid out for examination. Akhavan’s choice of material is significant, as bronze is linked with ancient Mesopotamian weaponry as well as historical memorials and monuments. The horizontal display on the floor is unlike the traditional vertical orientation of commemorative sculptures. Instead, it evokes makeshift funerary displays, sites of mass burial or piles of shrapnel.

The work draws on research that Akhavan has carried out at Kew Gardens in London and at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. Drawing on the botany and history of Iraq, the work reconsiders monument-making by shifting away from traditions of human-centric memorialisation.