Paul Cezanne. The Basket of Apples, c. 1893. The Art Institute of Chicago, Helen Birch Bartlett Memorial Collection.

Introduction

Paul Cezanne (1839–1906) is one of the most highly regarded and enigmatic artists of the late 19th century. By approaching painting as a process and investigation, where uncertainty plays an integral role, he gave this medium a new lease of life. Cezanne linked the formal process of art-making he called ‘realisation’ to his personal experiences, or ‘sensations’. His work has always strongly resonated with other artists, and this legacy continues into the present day.

The exhibition opens with one of Cezanne’s early self-portraits. In his 30's, he depicted himself as a mature, self-assured and sophisticated modern man. He then spent the following 30 years wrestling with what it meant to be a modern painter. At the same time, he remained deeply sceptical about the world he lived in, from political unrest in France to a continually accelerating way of life. This study of the self is displayed alongside a still life of apples, Cezanne’s most celebrated subject, through which he investigates our relationship with the object world.

The first half of the exhibition looks at Cezanne in the context of his time, exploring his life, relationships and the creative circle that surrounded him. The second half presents groups of works that focus on particular themes, including his radical still lifes and studies of bathers. Some labels include the names of artists who owned the paintings. You can also look out for captions written by artists working today, responding to Cezanne’s influence.

Becoming Cezanne

In 1861, 22-year-old Cezanne’s future lay at a crossroads. His father wanted him to remain in his home town Aix-en-Provence in southern France and pursue a career in law. His school friend, the writer Émile Zola (1840–1902), who had established himself in Paris, encouraged Cezanne to join his avantgarde creative circle and pursue an artistic career. Cezanne chose the latter, but he would never truly settle in Paris. Living between Provence and Paris became a lifelong habit that strongly influenced his working practice, style and career.

Paris was in the midst of a turbulent social and urban transformation. As the cultural centre of France, the city gave Cezanne access to the resources he needed to thrive as an artist. He made studies of sculptures and paintings in the capital’s museums, and sketched life models at the independent art school Académie Suisse. Here he met his friend and mentor Camille Pissarro (1830–1903). Together with a group of other young ambitious artists they developed new techniques, approaches to composition, and ways of using colour. This change, known as the impressionist revolution, dramatically modernised painterly practice in Europe, which had remained broadly unchanged since the 15th century.

Cezanne’s relationships with Zola and Pissarro were key in developing his style and subject matter. Their influence saw his paintings evolve from dark, violent, thickly painted compositions such as Sugar Bowl, Pears and Blue Cup (on display nearby), to the more colourful and considered style of Still Life with Fruit Dish (on the opposite wall).

Once in Paris, Cezanne cultivated a reputation for himself as an outsider from Provence, opposed to fashionable metropolitan tastes. In tandem with Zola’s gritty realistic style of writing, and reflecting the turbulent times, Cezanne painted modern scenes of violence and degradation. The sexualised imagery he often included alludes to society’s discrimination against women as well as a preoccupation with their changing roles in public life.

Violence in the world called for a violent painting technique. Cezanne would describe his early style as ‘ballsy’. He viewed this as a virile antidote to the stale traditional approach to painting taught at the prestigious art school the Académie des Beaux-Arts, or the officially approved works displayed at the annual state sponsored Salon competition. While many of Cezanne’s works took their cues from the traditional genre of history painting, the combination of his raw style, contemporary settings and a disregard for bourgeois morality set the artist apart.

Cezanne and Pissarro met in 1861 at the Académie Suisse. Though Cezanne continued to spend time in the south, between 1872–82 the two often lived near each other in Pontoise and Auvers-sur-Oise, just outside Paris. Here they worked side-by-side, learning by watching each other paint. Pissarro was nine years older than Cezanne, who once wrote Pissarro ‘was like a father to me’. Cezanne adopted a lighter and more colourful palette from Pissarro. He also learned how to treat proximity and distance with care on a two-dimensional picture plane. By the early 1880's Cezanne developed his signature technique of considered parallel brush strokes that permitted him to render his sensations. Cezanne’s unpopulated landscapes and pensive, intricately constructed still lifes would remain central to his art throughout his life.

Radical Times

Cezanne was never as politically outspoken as his friends. Pissarro was a committed anarchist, and Zola wrote in support of the republican movement. However, recent research has unveiled elements in Cezanne’s early work that question his remoteness from issues of modernity. This room reveals his interest in popular visual culture and political topics. We look at three works in focus, exploring how he carefully considered the subjects he chose to depict. In Scipio we look at the possible influence of abolitionism on Cezanne, while The Eternal Feminine addresses imagery from the popular press, and The Conversation subtly hints at Cezanne’s political views.

Cezanne lived through times of extreme political and social upheaval. Paris had been subject to a cycle of violent power struggles since the French Revolution in 1789. Different groups fought between competing visions of France: as a monarchy, a republic, or an empire. In the provinces, regionalist movements for cultural self-determination were gaining force. In the capital, sweeping urban modernisation caused displacement and further social unrest. In 1870–1 Prussia invaded and defeated France after the long brutal siege and subsequent fall of Paris. Months later, the Paris Commune, a workers’ uprising against the French government, was brutally suppressed. Globally, tensions and debates around slavery continued following the American Civil War, while France and other European colonial empires were reaching the peak of their exploitative powers

The Conversation

Cezanne was an avid reader of contemporary media. His interests spanned from left-wing press and popular broadsheets to illustrated magazines. During the FrancoPrussian War, Cezanne worked on three paintings based on fashion plates from the Parisian magazine La Mode Illustrée. In two of them, his approach was to create a painterly version of the lithograph. But in The Conversation he copied the magazine image then added two male figures on the right, and the French tricolour flag on the centre left. Later, a plaque was attached to the frame which suggests the work has been seen as a portrait of Cezanne’s sisters, Rose and Marie, and his friends, Anthony Valabrègue and Antoine-Fortuné Marion. Cezanne’s interest in popular imagery and politics has not often been discussed. His inclusion of the flag might represent a rare political or patriotic assertion made during a time of great turmoil.

The Eternal Feminine

Like many of his works, Cezanne did not title this painting and watercolour. They were later titled The Eternal Feminine – a phrase used in Europe at the time to describe idealised qualities attributed to women. Cezanne surrounds the female nude in the centre with figures representative of French society, including clerics, merchants, lawyers, entertainers, bankers and an artist depicting the scene.

The composition may be inspired by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Cezanne’s favourite 19th-century artist. Recent scholarship suggests the content reflects political cartoons from the 1870s popular press. In the image reproduced here, the female allegorical figure represents Paris. Cezanne’s female nude with disturbing red eyes, crowded by men, might be read as a comment on the political and social state of modern French society.

Scipio

Scipio 1866-8

This large-scale and ambitious early portrait depicts the Académie Suisse model known as Scipio. Despite extensive research, not much information survives about him. The painting was made just after the American Civil War and 20 years after France ended slavery across its Empire. From friends such as Pissarro, raised in the Danish colonies of the Caribbean, and Puerto Rican painter Francisco Oller (1833–1917), a firm abolitionist, Cezanne was aware of debates around enslavement. Scholars argue that Scipio could be a nickname taken from the anti-slavery book Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, published in France in 1853.

This work was owned and treasured by Monet and more recently researched by contemporary artist Ellen Gallagher. She writes here about connections she makes between the painting and a photograph of an enslaved man, known as Gordon, whose story was told by abolitionists through widely circulated photographs that appeared in the 1860s, including in Harper’s Weekly (illustrated here).

Family Portraits

Cezanne and Marie-Hortense Fiquet (1850–1922) met in 1869. Like Cezanne, Fiquet’s family had moved to Paris from the provinces. Fiquet worked as a bookbinder in her father’s shop. Defying the social conventions of her middle-class upbringing, she moved in with Cezanne while they were not married, and remained his life-long companion and model. Known as ‘Madame Cezanne’, Fiquet and the artist eventually married in 1886, although by this time they were mainly living apart. There are 29 known portraits of Fiquet, painted over the next 25 years, more than any of his other models. This body of work testifies to the continuous closeness, rapport and partnership between the artist and his favourite, most patient model.

Also displayed in this room are portraits of Cezanne and Fiquet’s son, Paul. He was born in 1872 and brought up largely by his mother. For years Cezanne tried to hide his young family from his overbearing father, worried that he would remove the struggling artist’s much-needed allowance.

Cezanne rarely worked with professional life models, preferring those he knew well. His careful repeated study of sitters’ features and poses over the years allowed him to give presence to his models without commenting on their character. The artist’s close relationship with family members was key in affording him the time to experiment, hone and master his portraiture practice.

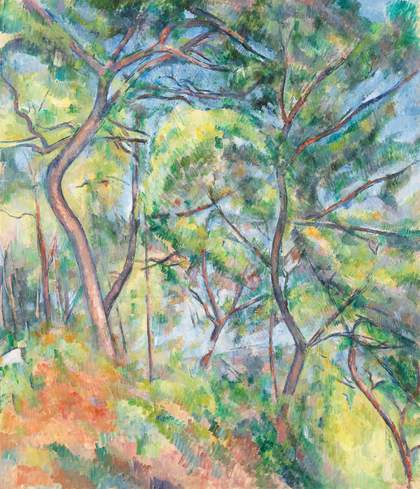

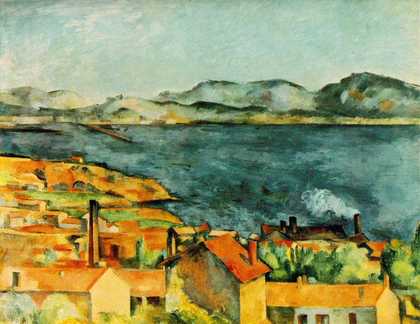

L’ESTAQUE: BETWEEN THE SEA AND THE MOUNTAINS

The Bay of Marseille, Seen from L'Estaque c.1885

In his youth, Cezanne holidayed in the southern coastal village of l’Estaque, located on the bay of Marseille, close to Aix. He would go on to visit with his partner and son, the village becoming a place of refuge. In relative isolation, away from the concerns of the outside world, the artist could concentrate on painting.

His first lengthy stay was in 1870–1, when he hid in l’Estaque to avoid military conscription in the Franco-Prussian War. Here Cezanne could also prevent his father from discovering his relationship with Fiquet. During many visits over the next 15 years, Cezanne painted more than 40 known paintings of the village and its rocky surroundings. The artist’s early paintings of the area show how he engaged with the local geology, adapting his brushstrokes to reflect the rugged surfaces of sunlit rocks.

During a visit in 1876, Cezanne wrote to Pissarro, describing the views as ‘like a playing card. Red roofs against the blue sea’. In comparison to northern French landscapes, Cezanne praised the light and unchanging vegetation which better suited the time he needed to complete his compositions. Through repeated observation and careful study of the same outdoor subject matter or ‘motif’, Cezanne began to realise his vision. Crucially, the artist discovered that his native region, Provence, contained the conditions and inspiration he needed to thrive. Commentators would later proclaim l’Estaque as the site where ‘Cezanne became Cezanne’.

Modern Materials

Cezanne engaged with a range of artistic media throughout his career. He worked with oil-based paint, watercolour, pencil, ink, charcoal and mixed media. He made works on canvas, on paper, and experimented with prints. He also adopted the same commercially produced tools and materials that had enabled the impressionist revolution – lightweight dismountable easels, primed (ready to paint) canvases of standardised sizes and in rolls that could be cut as required, tubes of oil-based paints and tins of watercolours. These enabled him to work quickly and outdoors.

Cezanne’s preference for a small range of colours, used in a particularly rich variety of shades, fascinated both his peers and art historians. According to the poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926), Cezanne used no fewer than 16 shades of blue that he mixed himself. Recent developments in conservation have shed light on the complexity of Cezanne’s technique and his engagement with specific media. We can also chart his changing financial circumstances, as this enabled or prevented his access to high-end materials.

Still Life: Continuous Research

Cezanne’s most focused and intense investigations took place in the highly controlled and isolated environment of his studio. Here he would experiment with and elevate the genre of still life painting, traditionally considered the least important of the art genres. In contrast to painting outdoors, in the studio Cezanne could control his subject – staging, arranging, propping and tilting the objects to his desired effect.

After inheriting his father’s estate, Jas de Bouffan, in 1886 along with his mother and sisters, Cezanne’s studio practice changed. He planned a group of paintings which followed a singular method, depicting the same objects repeatedly. In 1893–5 Cezanne painted a dozen canvases where his usual combinations of props – apples and pears, bottles, a ginger jar, sugar bowl, water jug – are connected by an intricately folded blue fabric. Produced locally in Aix until 1885 and known as l’indienne, the fabric takes centre stage in most of the works in this room.

Through repeating this narrow range of everyday, locally produced or readily available household objects, Cezanne reinforces the materiality of his still life compositions. The blues of the background flatten the picture space. Cezanne uses a rich and varied palette to define form with colour, emphasising the two-dimensionality of his painterly project. By producing these works together as a clearly defined group, Cezanne invites us to consider them as a whole, to look again, and to engage with his experimentation.

Mont Sainte-Victoire

Without doubt, Cezanne’s favourite and most emblematic landscape subject was Mont Sainte-Victoire, a limestone mountain that dominates Aix and its surroundings. Between 1882 and 1906 it appeared more than 80 times in his paintings and watercolours. In the 1880s Cezanne painted the mountain from the grounds of Jas de Bouffan. In the 1890s, he went on to depict it from the valley surrounding Aix and the town’s stone quarry, the Bibémus. Finally, he worked from a vantage point above his last studio in Les Lauves just north of Aix. Today, Cezanne’s paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire are his most internationally appreciated landscapes, featuring in collections from Japan to South America.

An ongoing study of the known and the familiar was at the core of Cezanne’s creative project. His landscapes, devoid of human presence, represent a decisive step away from 19th-century romantic and allegorical painting. They also mark a shift from impressionism’s ambition to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. Cezanne learnt about the geography and geology of the mountain ridge from his childhood friend, naturalist Antoine Fortuné Marion (1846–1900). This knowledge, together with his methodical observation of the mountain, enabled Cezanne to create a new sort of landscape that deeply engaged with the terrain of his homeland. Instead of capturing a passing moment, Cezanne strived to convey a geological embodiment of timelessness.

BATHERS: TRADITION AND CREATIVITY

Cezanne reportedly boasted to his young poet-friend Joachim Gasquet (1873– 1921) that he ‘wanted to make of impressionism something solid and enduring like the art of museums’. This informed the artist’s life-long engagement with the theme of bathers, which follows a long classical tradition of depicting nude figures in imaginary landscapes. Cezanne’s bathers were inspired by his sketching trips to the Louvre. They first appeared in early tense and violent works such as The Battle of Love 1879–80 (seen in room 2) and through the crudely painted male bodies of Bathers at Rest 1875 (in this room).

Cezanne’s bathers also reveal the very modern approach of working through appropriating other imagery. Instead of sketching from life models, he continuously studied paintings and sculptures in museums, drew from écorché figures (sculptures that reveal muscles and anatomy) and photographs of models. He began by depicting single figures, or groups of male and female bathers, freeing them from allegorical context or narrative. Over the years, curvaceous female forms and muscular male bodies turn into almost androgynous figures, set in non-specific outdoor surroundings.

The bathers are among the very few large-scale canvases Cezanne produced after the 1870s. For the last ten years of his life, he worked on three monumental Large Bather compositions, constantly changing the figures’ positions, shapes and outlines. He repeatedly extended the sizes of canvases, adding layers of paint, and experimenting with pigments, tonality and mark making. All three paintings were still in Cezanne’s studio the day he died – a testimony to his continuous research and experimentation through this theme.

CEZANNE: THE ARTIST’S ARTIST

Throughout his life, Cezanne turned to museums to study and draw sculptures and paintings from the past. Some of these drawings are displayed in this room. In his bather scenes, Cezanne inserted figures and poses he had carefully studied, adapting them within the new compositions. He once said: ‘We turn to the admirable works handed down to us through the ages, where we find comfort and support, like the plank for the [struggling] bather.’ The works of the 17th-century French sculptor Pierre Puget (1620–1694), also from Provence, were particularly meaningful for Cezanne, as we saw in room 7 and again here.

In turn, generations of artists have been drawn towards Cezanne’s bathers for ‘comfort’ and ‘support’ in their own practice. Proportionally, artists have since purchased more of Cezanne’s bather works than any other subject. British sculptor Henry Moore (1898–1986) once owned Three Bathers, which we encountered in room 2. Here, we see works from the collections of artists such as the Spanish Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), French Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and North American Jasper Johns (born 1930). Describing Cezanne’s influence, Matisse said: ‘In moments of doubt, when I was still searching for myself, frightened sometimes by my discoveries, I thought: “If Cezanne is right, I am right”; because I knew that Cezanne made no mistake.’

1899–1906: SLOW HOMECOMING

1899 was a watershed in Cezanne’s life, marked by irreversible change. Following his mother’s death in 1897, the family estate Jas de Bouffan was sold. Later that year the artist sold the contents of his Paris studio to dealer Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939) and reputedly destroyed many of his early works. By then Cezanne was diagnosed with diabetes and feeling increasingly frail. The artist’s concerns surfaced in moody dark landscapes and ominous compositions with skulls.

Despite this, during the last six years of his life Cezanne was pushing against mortality with bursting creativity. He designed his first purpose-built studio in Les Lauves. Here Cezanne explored the painterly possibilities of thick oils and delicate, luminous watercolour washes. For the first time in his career, he took the easel out of the studio to paint portraits of people bathed in direct sunlight. In works such as The Gardener Vallier he set solitary figures alongside lonely trees. He also created an increasingly atomised representation of the isolated summit of the mountain in Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves.

The last years of Cezanne’s life are documented in the most detail. He was visited by peers and younger artists keen to pay respects to the legendary painter. Their accounts, paintings and photographs (as seen in rooms 2 and 6) reveal Cezanne at his most revered, yet modest. Cezanne remains an innovator whose very personal engagement with the local, and endeavours to develop a new visual language, bridged tradition and modernity.