Who is he?

Wifredo Lam was a Cuban-born artist, best known for his large scale paintings which reference modernist aesthetics and Afro-Cuban imagery to explore themes of social injustice, spirituality and rebirth.

Born in the small town of Sagua la Grande at the turn of the century, his father was a Chinese immigrant and his mother a descendent of both Spanish conquistadors and African slaves. Lam’s distinctive style and exploration of Afro-Cuban visual culture, alongside his knowledge of European modernism, made a huge impact on the art world. Through his work, Lam was able to challenge assumptions about non-European art and examine the effects of colonialism.

Having pursued a successful career within avant-garde circles on both sides of the Atlantic, he can be considered one of the most important artists to come out of the twentieth century.

Wifredo Lam Self-Portrait 1926 Private collection, Paris © SDO Wifredo Lam

How did he start his career?

In 1916 Lam moved to Havana, initially to pursue a career in law and later studying art at Havana’s School of Fine Arts. He quickly began to exhibit in annual salons and establish himself as a young artist, specialising in a traditional realist style and mostly painting landscapes and still lifes.

Showing signs of artistic promise, Lam received a scholarship to study at the Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid. There he became part of a vibrant cultural circle, training under the portraitist Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor. During this time, Lam became greatly motivated by his trips to the Prado Museum, where he encountered the works of Diego Velázquez, Hieronymus Bosch and Francisco de Goya. Inspired by Goya’s studies of political corruption, Lam went on to use his own work as a way of condemning the horrors of war.

Wifredo Lam Hanging Houses, III 1927 The Rudman Trust © SDO Wifredo Lam

What are the common themes within his early work?

In 1931, after only two years of marriage, Lam lost both his first wife and infant son to tuberculosis. Overwhelmed by this personal tragedy, he later stated ‘my grief deprived me of all enthusiasm for life’. This sorrow is reflected in some of Lam’s early work.

In 1936, Lam fought for the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. The turmoil of this experience also became a frequent theme within his paintings, which concentrated on dynamic groupings of figures.

Who was he influenced by?

Lam relocated to Paris in 1938. While there he befriended Pablo Picasso, who introduced Lam to leading artists, including André Breton, Joan Miró and Óscar Domínguez, and writers such as Benjamin Péret and Pierre Mabille. During this time Lam’s work moved towards a modernist style, as he began to experiment with cubist techniques and showed an interest in the surrealists’ exploration of the subconscious and automatism.

While Lam became an active member of the surrealist movement, he also stated that ‘surrealism gave me an opening, but I haven’t painted in a surrealist manner’. For this reason Lam has become difficult to define as an artist.

Wifredo Lam Untitled 1939 Private collection (The Rudman Trust) © SDO Wifredo Lam

Wifredo Lam Young Woman on a Light Green Background 1938 Private collection, Paris © SDO Wifredo Lam

How did Cuba impact his work?

After eighteen years away, Lam returned to Havana in 1941 as part of the exodus of refugees fleeing the German occupation. Upon his return after years in Europe, he was dismayed to still see racial inequality and political corruption in his home country. As such, Lam used art to explore Cuban culture and identity.

Lam increasingly made reference to Cuba within his work, stating ‘I wanted with all my heart to paint the drama of my country’. Rediscovering the natural landscape, he often depicted Cuba’s vegetation and used an earthy colour palette as well as vibrant greens, reds and oranges of the Caribbean isles. Lam continued to develop this signature style, incorporating elements of Afro-Cuban imagery.

At this time, Lam also became fascinated with the Santería religion, in which rituals and beliefs from West Africa are overlaid with aspects of Catholicism. During both Santería and Vodou rituals, the latter of which he encountered on an extended visit to Haiti, the worshipper is allegedly possessed or ‘ridden’ by a spirit. The influence of these ceremonies is evident within Lam’s work, which commonly depict mask-like faces and hybrid figures including the ‘horse-headed woman’. These figures can be interpreted as poetic references to the sex workers present in pre-Revolutionary Cuba, as Lam commented on his homeland’s poverty and corruption.

Impressed by the social ideals of the Cuban revolution, Lam returned to Cuba periodically. His final visits to Havana were for medical treatment following a stroke in 1978.

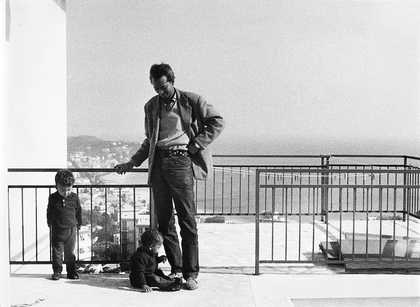

© Archives SDO Wifredo Lam

What are his key works?

Wifredo Lam Self-Portrait, II 1938 © The Rudman Trust

Self-Portrait II 1938

Lam made only a small number of self-portraits throughout his career. This self-portrait from 1938 signifies his bohemian status as an artist. Shown in the colourful interior of his studio, Lam holds himself purposefully, yet he avoids direct eye-contact with the viewer. He would later go on to present himself in a much more abstract style.

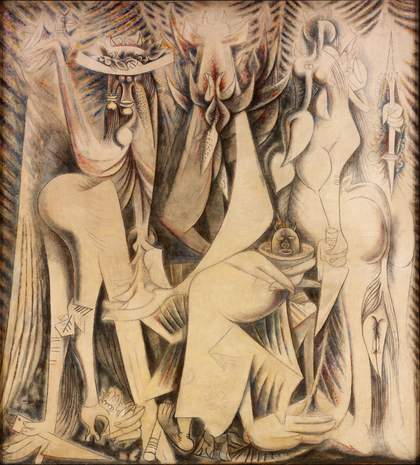

Wifredo Lam The Jungle 1943 Museum of Modern Art, New York © SDO The Estate of Wifredo Lam

The Jungle 1943

Completed in 1943, The Jungle is considered Lam’s breakthrough piece of art. The large scale painting depicts hybrid male and female figures within a crowded Cuban jungle, their bodies merging between human, animal and plant. The faces appear mask-like, while their breasts, buttocks and genitalia are exaggerated and eroticised. The artist explained that ‘in The Jungle and in other works I have tried to relocate Black cultural objects in terms of their own landscape and in relation to their own world’. Unfortunately, as the work was painted onto large pieces of kraft paper, it is too fragile to travel.

Wifredo Lam The Eternal Present (An Homage to Alejandro García Caturla) 1944 Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design (Providence, USA) © SDO Wifredo Lam

The Eternal Present (Homage to Alejandro García Caturla) 1944

Lam considered this work a direct comment on his home country and its corruptions. He later explained that the woman on the left represented ‘the paradise that foreigners seek in Cuba, a land of pleasures and sickly-sweet music’. Others have interpreted the figure as Oshun, the Orisha of love, depicted alongside warrior deities Elegua and Ogun, the Orisha of war. Together they come to represent resistance to the corruption of Cuba by imperialist powers.

Alejandro García Caturla was a Cuban composer and judge, who was murdered in 1940 by the defendant in a trial he was to oversee that same afternoon.

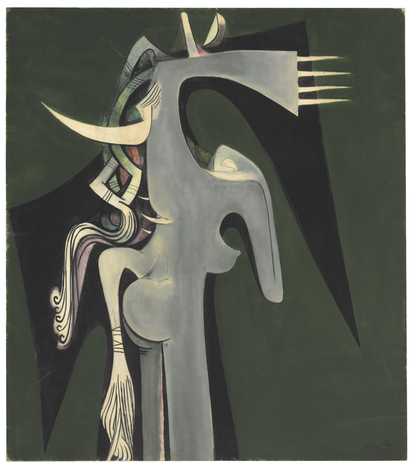

Wifredo Lam Horse-Headed Woman 1950, The Rudman Trust © SDO Estate of Wifredo Lam / Photo: Joaquín Cortés y Joaquín Lores, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

Horse-Headed Woman 1950

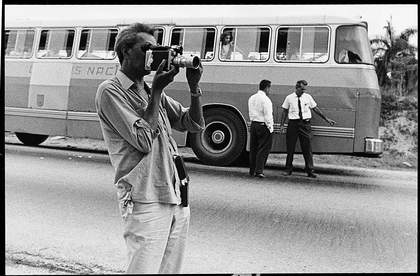

In 1950, Lam was visited by Art News journalist Geri Trotta and photographer Mark Shaw. Together they documented Lam creating this work, gaining a unique insight into the artist’s practice and home life. Unpublished photographs show that Lam’s initial design for the painting was on a scrap of paper. The artist then applied multiple washes of paint, thinned with turpentine, onto a canvas. The article suggests that Lam found this a torturous process, stating ‘all art is tragedy…for me, painting is a torment’.

What the critics said …

Lam is one of the most fascinating figures in the history of modern painting.

Alastair Sooke, Art critic

Lam has an Oriental facility for design. He composes as naturally as he breathes.

Gerri Trotta, Art critic, 1950

We can appreciate how these symbols … are arranged together with such rhythmic skill and clarity, that their rational organisation almost exorcises their terror.

John Berger, Art critic

His art is the last tarot of surrealism and a tropical wonder of modern painting.

Jonathan Jones, Art critic

Wifredo Lam in quotes …

Mark Shaw Wifredo Lam, Havana 1950 © Mark Shaw mptvimages.com

- ‘As I work, I do everything intuitively’.

- ‘When I arrived in Paris, after the fall of the Spanish Republic to the fascists, I began to paint what I felt most deeply […] this strange world started to flow out of me’.

- ‘Africa has not only been dispossessed of many of its people, but also of its historical consciousness … I have tried to relocate Black cultural objects in terms of their own landscape and in relation to their own world’.

- ‘My painting is an act of decolonization not in a physical sense, but in a mental one’.

Visit The EY Exhibition: Wifredo Lam at Tate Modern, 14 September 2016 – 8 January 2017.