Anni Albers in her weaving studio at Black Mountain College, 1937. Photo by Helen M. Post Modley. Courtesy of Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina.

1. Take the opportunity and run with it

I was told that there wasn't a chance to get into that [stained glass] workshop because there were so very few chances to execute a stained glass window. And there was one man that was already there; that was all. So the only thing that was open to me was the weaving workshop. And I thought that was rather sissy.

Anni Albers, 1968

Life at the Bauhaus, 1928 Photographer unknown © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann was born in Berlin in 1899 to an affluent family. She studied drawing and painting which went against her family’s expectation to follow a traditional lifestyle. She tried to study painting under Oskar Kokoschka’s supervision but he discouraged her to continue. Later she decided to study at the innovative Bauhaus school. Though her first application was rejected, she finally got accepted into the school. She took some basic instruction for the first two terms and then chose weaving as her specialism. This was not her first choice but one of the few options available to women.

2. Challenge the norms

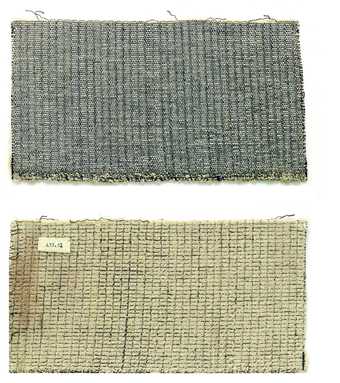

Anni Albers Front and back of the wall-covering material for the auditorium of the Trade Union School in Bernau, Germany 1929 © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Galleries and museums didn’t show textiles, that was always considered craft and not art. […] When it’s on paper it’s art.

Anni Albers, 1984

Anni Albers played an integral role in framing textiles as an art form. With her career as a teacher, a designer and an artist she put textiles on the map. Her approach towards textiles was inspired by ancient textile traditions. At the same time, she made work designed for functional and practical use.

Albers designed a wall-covering for a Trade Union School’s auditorium. She later submitted this as her final diploma project at the Bauhaus. In this early work, she used cellophane, a new material at the time, as well as plain cotton and chenille to create a fabric that is sound-absorbing and light-reflecting. While making her material and formal choices for this work, she paid great attention to its purpose. With this fabric, Albers avoided complicated patterns or bold colours which could distract from its function.

3. Travel as much as you can

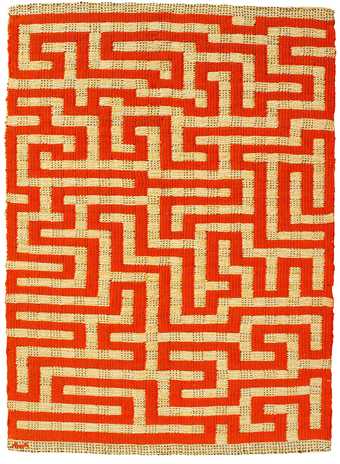

Anni Albers Red Meander 1954 Private Collection © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

To my great teachers, the weavers of ancient Peru.

Anni Albers, 1965

In 1933, Anni Albers and her husband Josef Albers left Germany to seek refuge from the rise of Nazism. They moved to the United States and started teaching at Black Mountain College. During her time in America, she travelled to Mexico, Cuba, Chile and Peru. She also travelled frequently to Europe to design, make prints and to lecture.

Travel played an important role in Albers's life and career as an artist. Her trips to South America had a profound influence on her work. She became fascinated with ancient South American weaving methods. One of her most important works, Red Meander (1954) is inspired by an ancient labyrinth and the Peruvian patterns she studied so closely. This work was later recreated as a series of screenprints.

4. Learn from the past

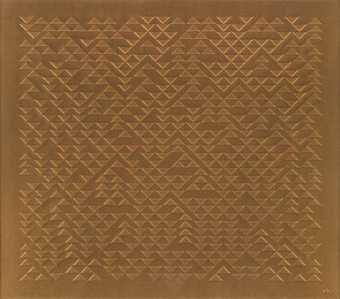

Anni Albers Ancient Writing 1936 Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of John Young © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Wonderful ancient art, frequently almost unknown, hardly excavated even when it is known.

Anni Albers, 1936

Albers was interested in the ancient uses of threads as means of visual expression and communication. In her publication On Weaving she discusses how Peru has one of the greatest and most intricate traditions of expressive weaving. She mentions that this country did not develop a written language up until the 16th century. On the other hand, she was not interested in textile traditions that were trying to copy painting, such as Renaissance or Gothic textiles. She believed these western traditions had played a role in bringing textiles down to being a decorative and minor art form.

Albers was captivated by ancient methods of weaving. At the same time, she was keen to employ these methods in a way that is compatible with modern modes of production. She believed that even in modern mass production, problems usually require simple solutions that can be learned from the past. Slowness and experimentation characterised her best work.

In Ancient Writing Albers used weaving as a tool to convey abstract thoughts. She did not want her works to be easily decoded. In her own words, the formal arrangement of a work needed to have “that quality of mystery that we know in nature”.

5. Make useful art

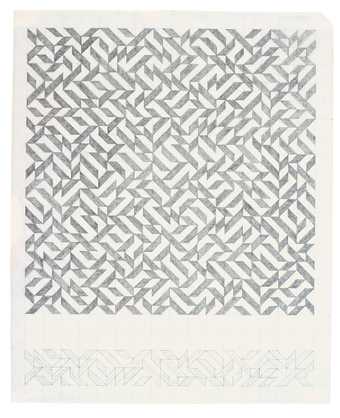

Anni Albers Untitled c.1974 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

The conscientious designer, does not himself design at all but rather give the object-to-be a chance to design itself.

Anni Albers, 1958

Albers believed design has elements of usefulness, planning and organisation. Design has to be combined with sensitivity and imagination to become art. The Bauhaus ideology of ‘art for everyone’ inspired Albers's artistic career. In 1951, she started a collaboration with Knoll textile department that led to a 30-year partnership. She designed a range of furnishing fabrics that are still in production. Created for Knoll in the 1970s, Eclat is one of her most-copied designs that still looks very contemporary.

6. Get your hands dirty

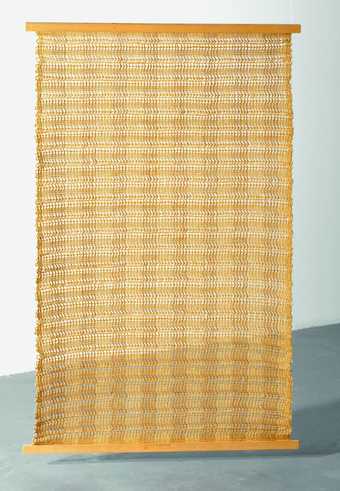

Anni Albers Free-Hanging Room Divider circa 1949 Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of the designer © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

All progress, so it seems, is coupled to regression elsewhere. We have advanced in general, for instance, in regard to verbal articulation — the reading and writing public of today is enormous. But we have grown certainly increasingly insensitive to our perception of touch — the tactile sense.

Anni Albers, 1965

Albers championed modernity. However she was concerned that modern humans had lost their sensitivity to touch. She saw the rise of ready-made products as a reason for this. As an artist and a designer she was conscious of creating works that appealed to our sense of touch.

Free-hanging room divider, a woven partition, is one of her most innovative designs. In this work, tactile qualities of the surface and structural qualities, such as choice of material, come together. She used materials such as jute and Lurex -a synthetic thread made from a metallic film. Use of rigid material allowed for an open-weave arrangement.

7. Embrace emotion

Anni Albers Six Prayers 1966-1967 The Jewish Museum, New York, Gift of the Albert A. List Family, JM 149-72.1-6 © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Well you all know how great art can affect you, you breathe differently.

Anni Albers, 1982

In 1965, The Jewish Museum in New York approached Anni Albers. They wanted her to produce a memorial to the six million Jewish people who died in the Holocaust. Six Prayers, was the work that resulted from this commission. She spent the majority of her career developing a language of abstraction that could express emotions without the use of words. The work is composed of six beige, black, white, and silver vertical- woven panels. Her choice of colours and patterns is simple and graceful. This is a memorial that is far more meditative than monumental.