This major retrospective is the first Warhol exhibition at Tate Modern for almost 20 years. As well as his iconic pop images of Marilyn Monroe, Coca-Cola and Campbell’s soup cans, it includes works never seen before in the UK. Twenty-five works from his Ladies and Gentlemen series – portraits of black and Latinx drag queens and trans women – are shown for the first time in 30 years.

Exhibition Tour

Join curators Gregor Muir and Fiontán Moran as they discuss Warhol through the lens of the immigrant story, his LGBTQI identity and concerns with death and religion.

Popularly radical and radically popular, Warhol was an artist who reimagined what art could be in an age of immense social, political and technological change.

Explore the artist's life and career in these 12 rooms.

ROOM 1: ANDREW WARHOLA

Andy Warhol

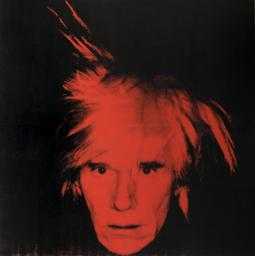

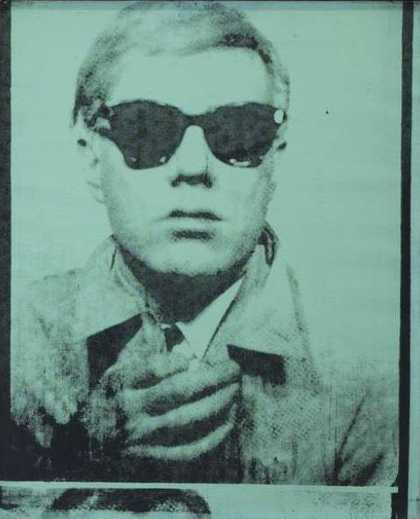

Self-Portrait 1964

Private Collection

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

Andy Warhol produced art at a time of immense social, political and technological change. This exhibition examines Warhol’s subject matter, his experiments in media and the way he cultivated his public persona. It draws attention to Warhol’s personal story and how his view of the world shaped his art.

Born in 1928 in the industrial town of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Andrew Warhola was the third son of Andrej and Julia Warhola. His parents were Carpatho-Rusyn, and had emigrated from Miková, a mountain village in what is now Slovakia. Warhol was brought up Ruthenian Catholic, attending church throughout his life. Religious imagery and the glamour of Hollywood movies interested him from a young age. He would draw with his mother and took art lessons at his local museum. When Warhol’s father died in 1942, he left his savings for his youngest child to go to college, where he studied pictorial design. In 1949, at the age of 21, Warhol moved to New York to work as a commercial illustrator. During this time, he permanently dropped the ‘a’ from his surname. His mother joined him in New York a few years later. She helped with his illustrations and lived with him until shortly before her death in 1972.

As a gay man growing up at a time when sex between men was illegal in the United States, Warhol embraced New York’s queer community of designers, poets, dancers and artists. Warhol’s first exhibitions in the 1950s featured line drawings of young men. Abstract expressionist art dominated the US art world. Warhol was considered too camp, or what some referred to as ‘swish’, and overly connected to the commercial world of advertising illustration to be a serious contender. It would take another decade before he found success as an artist

ROOM 2: SLEEP

Andy Warhol

Sleep 1963

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

From the start of his career, Warhol used his intimate personal relationships with people to create new ways of looking at the world. His first serious art film was Sleep, made over several nights in summer and autumn 1963 with a 16mm camera. The film shows 22 close-ups of the poet John Giorno, who was briefly Warhol’s lover, as he sleeps in the nude. Warhol was fascinated by the ability of his friends to stay up for days on end while using drugs and wondered whether sleep would soon become obsolete.

Warhol shot around 50 reels of film for Sleep, each one lasting only three minutes. He edited them with Sarah Dalton, who recalled, ‘he asked me to edit it, taking out bits where John moved too much – he wanted the movie to be without movement. I protested that I hadn’t a clue how to edit, but he fished out an old moviola editing machine, showed me how it operated and so to work I went.’ The final version repeats many scenes and lasts over five hours. It is projected in slow motion, giving a dream-like feel.

By documenting a single action with no dramatic narrative, Warhol turned film into something that could be treated like a painting hanging on the wall. John Giorno said that Warhol got round the homophobia of the art world ‘by making the movie Sleep into an abstract painting: the body of a man as a field of light and shadow.’

ROOM 3: POP

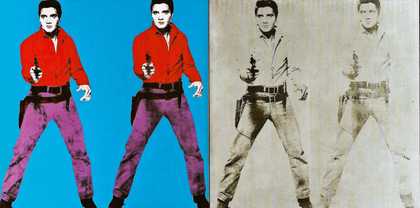

Andy Warhol

Elvis I and II 1964

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift from the Women's Committee Fund, 1966

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

Although he was a successful illustrator, Warhol still wanted to be taken seriously as an artist. Inspired by the new wave of art he saw in New York galleries, in 1960 he started making hand-painted pictures combining advertising imagery with expressive painting. This soon gave way to a clean graphic style now known as Pop Art. Warhol grew up eating watered-down ketchup with salt for soup. His images of consumer items such as Campbell’s soup cans are rooted in his experience of an emerging aspirational culture, selling a dream of economic and social progress.

Warhol was eager to speed up the process of replicating his images, so in 1962 he adopted the commercial production technique of screenprinting. He began to use photographs from newspapers and magazines, often depicting traumatic scenes. Screenprinting meant he could reproduce photographs onto canvas multiple times. While the printing process removed the artist’s hand, Warhol often allowed his screen to be over or under-inked. This created effects that disrupted the images. The face of film star Marilyn Monroe became almost mask-like, while the emotional impact of the news images in his Death and Disaster series was both emphasised and undermined. Some images, such as Pink Race Riot (Red Race Riot), which depicts peaceful civil rights campaigners being attacked by police, connected his work to broader social struggles and forced viewers to look at the world around them.

Warhol said creating pop art was ‘being like a machine’, as the process was often machine-like or mechanised. He then said, ‘everybody should be a machine’, as machines don’t discriminate. If we were all machines then ‘everybody should like everybody’, whatever their gender. Warhol’s open and fluid approach to his subject matter, to people, and the relationships between them, spoke to a decade of social change.

ROOM 4: The Factory

Andy Warhol

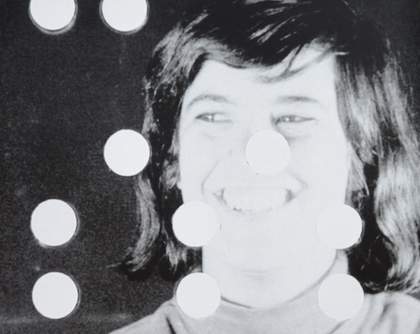

Screen Tests [selection] 1964-1966

Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh, USA)

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

An important part of Warhol’s fame was built through ‘the Factory’, which was an experimental art studio and a social space. Warhol set up the first Factory in 1963. After seeing his collaborator and former lover Billy Name’s silver apartment, he asked him to cover the Factory with silver paint and foil. It was the setting for the mass production of his paintings and sculptures, and the site of Warhol’s new interest in underground film making.

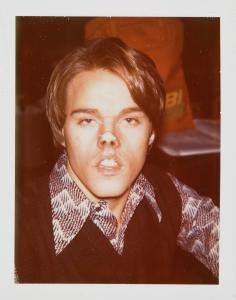

Warhol documented the people who passed through the Factory in his Screen Tests from 1964–6. Intended as film portraits, they emerged out of Warhol’s Most Wanted Men series of paintings (on display in room 3). The title refers to the Hollywood convention of filming new faces to test their ‘screen presence’. Warhol’s subjects were simply left to be themselves. They sat in front of the camera with nothing to do but endure its gaze for the duration of the film reel.

Warhol and his collaborators made more than 500 films between 1963 and 1972. They ignored traditional methods of film making and were often unscripted. The films usually featured his ‘superstars’, a group of personalities who spent their time at the Factory. By the mid-1960s, the Factory scene had become a form of living artwork, as famous and as controversial as Warhol’s paintings. Reflecting on this period, Warhol recalled how his 1965 exhibition in Philadelphia was so crowded the art had to be removed from the walls. He said it had become ‘an art opening with no art! We weren’t just at the art exhibit. We were the art exhibit.’

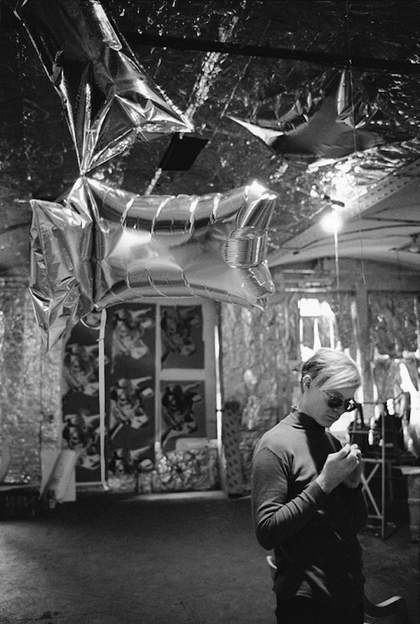

ROOM 5: SILVER CLOUDS

Andy Warhol

Silver Clouds 1966

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh IA1994.13

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

In 1965, at the height of his fame as an artist, Warhol announced his retirement from painting in favour of film making. He staged his farewell with an installation in a New York gallery the following year. One room consisted of nothing but wallpaper featuring a fluorescent pink cow. In the other, metallic silver balloons filled with helium floated through the gallery space and could be interacted with by the viewer. Titled Silver Clouds, they continued Warhol’s association with silver: in the silver Factory, his silver paintings, and his silver-grey wig.

Warhol described Silver Clouds, made with engineer Billy Klüver, as ‘paintings that float’. He wanted to upset conventional thinking about sculpture, specifically the dominance of minimalist art in the New York art scene at the time. This was an art based on order, mathematical precision and industrial materials. Instead, Warhol’s installation emphasised fluidity, movement and participation.

In 1968, the avant-garde choreographer Merce Cunningham asked to feature Silver Clouds for a performance of his dance piece RainForest. Warhol suggested that the dancers perform nude. Cunningham did not adopt this idea and asked the artist Jasper Johns to make the costumes instead.

Warhol’s Cow Wallpaper is installed in the exhibition café on this floor and in the Tate Kitchen on level 6.

ROOM 6: EXPLODING PLASTIC INEVITABLE (CURRENTLY CLOSED)

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable 1966, reconfigured 2013

Courtesy the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

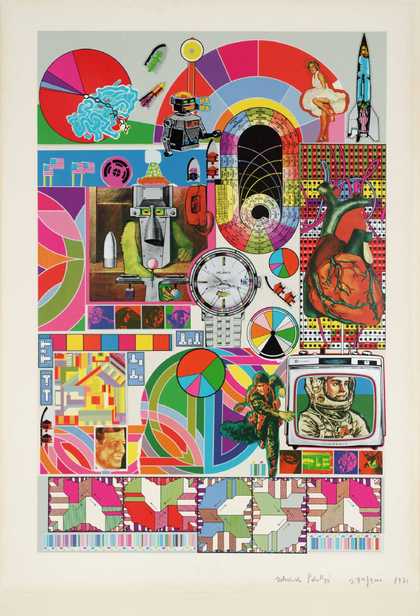

Working with members of the Factory, Warhol became interested in combining film with performance and music, expanding the idea of what cinema could be. In 1966 and 1967, he co-organised multimedia shows known as Andy Warhol’s Uptight and later as the Exploding Plastic Inevitable or EPI. The shows used new technology that has now become standard practice in live music gigs.

EPI featured musical performances by the Velvet Underground and Nico. Warhol’s films and still images were projected on top of each other. Coloured gels and strobe lights overlaid the projections, while Factory superstars, including Gerard Malanga and Mary Woronov danced with whips. The show managed to fascinate and alienate its audience. Velvet Underground singer Lou Reed described it as ‘a show by and for freaks’. It went on to tour music venues and college campuses around the US, and reinforced Warhol’s association with the counterculture.

Warhol also achieved his first commercial success in film at this time, with the release of The Chelsea Girls in 1966. This follows various ‘characters’, including ‘Pope’ Ondine, in and around New York’s Chelsea Hotel, and is presented as a double-screen projection. The final section of the film was shot in colour at the Factory and features layers of coloured light projected over Warhol’s superstars, which was also used for the EPI shows.

This room was designed by The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh to give an evocation of the EPI shows.

ROOM 7: THE SHOOTING

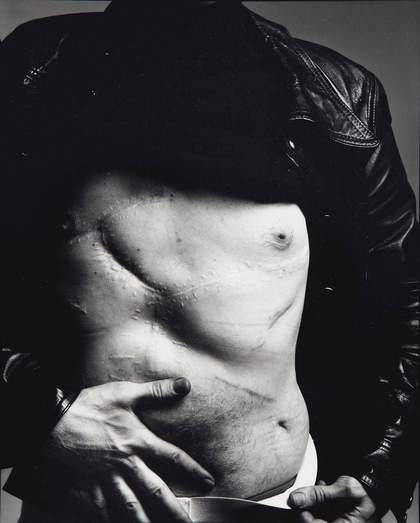

Richard Avedon

Andy Warhol, artist, New York, 20 August 1969

Nicola Erni Collection

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

As well as being fascinated with new media, Warhol used printed matter as a promotional tool and a space for experimentation. He published magazines, posters, books and designed record covers. At the beginning of 1968, the Factory moved to a new site on Union Square, as the original building was to be demolished. Warhol said the ‘silver’ period was over, and ‘we were into white now’. The new Factory had spaces dedicated to his magazine Interview and his film production.

On 3 June, the writer Valerie Solanas came to the Factory and shot Warhol, damaging his internal organs. Warhol was rushed to hospital and was declared clinically dead, but doctors managed to revive him. Solanas had been part of the Factory scene for a short time. She appeared in Warhol’s 1967 film I, A Man and had given Warhol the script for her play Up Your Ass, which was mislaid. She told the police Warhol was stealing her ideas. Her SCUM manifesto called for an end to the male sex and to capitalist society.

The shooting brought increased scrutiny of Warhol’s lifestyle and affected his physical and mental health for the rest of his life. He stopped the open-door policy of the Factory. He had trouble eating, had to wear a surgical corset, and became nervous around people he didn’t know. Despite the trauma of the event, he agreed to pose for photographer Richard Avedon and once compared the stitches of his chest to a Yves Saint Laurent dress.

ROOM 8: BACK TO WORK

Andy Warhol

Mao 1973

Yageo Foundation Collection Taiwan

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

After the shooting, Warhol passed most of his directing on to Paul Morrissey, who had worked on Warhol’s films since The Chelsea Girls. His business manager Fred Hughes sourced new portrait commissions from wealthy clients. These helped fund Interview magazine, edited by college graduate Bob Colacello, and ideas for TV shows, produced by Vincent Fremont. Warhol’s studio turned from an open social space to one focused on what he called ‘business art’. Warhol explained that ‘making money is art, and working is art - and good business is the best art.’

Warhol also started a serious personal relationship at this time. Jed Johnson moved in with Warhol in 1968, and they lived together for twelve years. Johnson edited a number of the Warhol-Morrissey films and directed Bad 1977, the final film Warhol produced. Julia Warhola’s ill health led to her return to Pittsburgh, and she died in 1972.

Warhol returned to painting in the 1970s with large-scale screen prints featuring a more expressive painting style and new subjects. He began with the Mao series in 1972, and continued exploring iconography with the Hammer and Sickle and Skull series of 1976. Warhol also experimented with other art forms. He vacuumed a gallery carpet as a performance and started his Factory Diaries: videos of life in the Factory and at home, including this tape of his mother Julia.

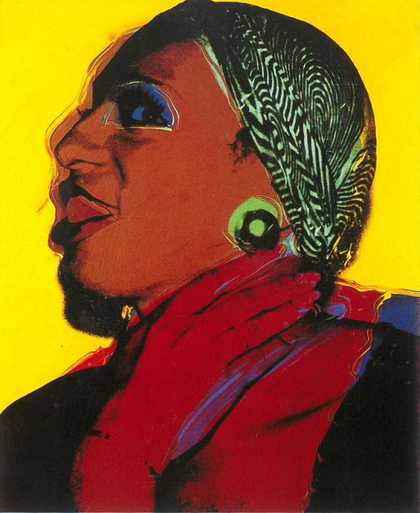

ROOM 9: LADIES AND GENTLEMEN

Andy Warhol

Ladies and Gentlemen (Iris) 1975

Italian Private Collection

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

Andy Warhol

Ladies and Gentlemen (Lurdes Wilhelmina Ross) 1975

Italian private collection

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

In 1975 Warhol produced a new series featuring anonymous Black and Latinx drag queens and trans women. Italian art dealer Luciano Anselmino commissioned the pictures and came up with the theatrical title Ladies and Gentlemen. This title implies Anselmino was less concerned with the lived experience of the models and more interested in the dramatisation of gender. The subjects were recruited via Warhol’s friends and from local drag bars and posed for a fee.

Warhol took over 500 photographs of 14 models. A selection of these were enlarged onto silkscreens. The result was a large group of paintings that deviated from the original proposal in favour of an exploration of performance, glamour and personality. In a similar manner to other works he created at the time, Warhol used expressive brushmarks and finger painting to explore the relationship between the silkscreen layer and the painted background. His films featuring the superstars Mario Montez, Holly Woodlawn and Candy Darling show Warhol was interested in depictions of gender expression. However, there are questions around the ethics of this series: he documented a community he was not part of, with the subjects having little agency in how they were depicted or where the works would be shown.

Given the lack of representation of trans people in art, there has been renewed interest in the series and the identity of the sitters. This room features seven of the models across 25 paintings. It includes Marsha ‘Pay it no mind’ Johnson who was present at the Stonewall Uprising that ushered in the gay and trans rights movements, and Wilhelmina Ross. Both Johnson and Ross performed as part of the drag theatre company ‘Hot Peaches’, founded by Jimmy Camicia, in off-off-Broadway shows. Little is known about some of the other figures, perhaps a record of the discrimination faced by trans people, especially those of colour.

ROOM 10: EXPOSURES

Andy Warhol

Torso 1977

ZOYA Gallery, Slovakia

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

By the 1970s, Warhol was himself an international celebrity. He was regularly photographed and took photographs at places such as the nightclub Studio 54, alongside public figures such as Grace Jones and Debbie Harry. Warhol famously went out every night, a condition he referred to as his ‘social disease’. As well as giving his work publicity, Warhol’s exposure enabled him to reinforce his distinctive public identity. Some US art critics dismissed his socialising and lucrative business of producing commissioned portraits for the rich and powerful as ‘selling out’. However, such activities also helped finance his more experimental art practices.

These social networks of collaboration and bodily performance found their way into Warhol’s new works, which were more explicitly based around the body. His Oxidation series from 1978 used human urine to oxidise metallic paint. The Torso series features male bodies, with some of the models recruited in gay bath houses by friends of Warhol, and brought back to the Factory to pose.

Warhol’s experiments with video extended into television projects, co-produced with Vincent Fremont, where he could reach an even larger audience. In 1980, he premiered Andy Warhol’s TV on a cable television network. He followed this in 1986 with Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes on MTV. It played on the artist’s fame, his network of celebrities and his obsession with recording, which he had been doing since the mid 1960s. The programmes followed the format of his Interview magazine by presenting intimate conversations between stars.

ROOM 11: MORTAL COIL

Andy Warhol

Statue of Liberty (Fabis) 1986

The Broad Museum (Los Angeles, USA)

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

As the 1980s progressed, Warhol’s work featured more political and religious imagery. Although it wasn’t deliberate, it reflected some of the major concerns of the time, including the Cold War between the US and the USSR and the escalating AIDS epidemic.

Warhol created images of the Statue of Liberty many times. It could be seen as the ultimate celebrity portrait. In Statue of Liberty (Fabis), Warhol laid military camouflage over this well-known symbol of freedom. The statue had personal meaning for Warhol. His family landed at Ellis Island, near to where Liberty stands, when they immigrated to the US. In this version, Warhol used a French biscuit tin lid, designed to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the statue arriving in New York as a gift from France. The Lenin series, created for a German gallery, saw Warhol return to the subject of communism and its most recognisable symbols.

Warhol had always used his own image in his art. In the 1980s, he created what came to be known as his ‘fright wig’ self-portraits for an exhibition in London. In earlier works, his wig was an integrated part of his appearance. In these pictures, his wig takes on the status of art. In contrast to his early self-portraits where he appeared aloof, in these works his gaunt face and intense expression convey the pain that he routinely suffered from since the shooting.

ROOM 12: THE LAST SUPPER

Andy Warhol

Sixty Last Suppers 1986

Private Collection

© 2020 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

Faith, death and desire come together in Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers. This large-scale work forms part of a series commissioned in 1986 based on Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. This famous mural depicts Jesus the night before his crucifixion with the twelve disciples. A copy of the mural had hung in the Warhola family kitchen. Da Vinci’s depiction has been damaged and repaired many times over the centuries. Warhol purposely used a cheap reproduction based on a 19th-century copy for his work. Choosing to copy a copy of the original, Warhol evokes the re-enactment of the Last Supper that takes place during every Mass. It also plays on the authenticity of da Vinci’s Last Supper, with Warhol stating: ‘It’s a good picture… It’s something you see all the time. You don’t think about it.’

Unlike most of his paintings, Warhol’s Last Supper series focuses on a group scene. The repetition of an image showing collective activity between men adds to the work’s symbolism. It was created soon after the death of Warhol’s former partner Jon Gould from an AIDS-related illness, and at a time when the private lives of gay men were facing the glare of the media. While Warhol was not a queer activist, Sixty Last Suppers could be seen as a moving portrayal of endless loss, reminiscent of ‘columbarium’, the wall graves found in many cemeteries.

Sixty Last Suppers would turn out to be one of Warhol’s final works. After the first exhibition of the series in Milan, he returned to New York where he reluctantly checked in to hospital for gallbladder surgery. While the operation was a success, his long-term ill health led to his heart failing, and Warhol died on 22 February 1987, aged 58.

Andy Warhol is presented in The Eyal Ofer Galleries. This exhibition is in partnership with Bank of America. With additional support from the Andy Warhol Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members.