Marie Smith during the Capturing the Moment workshop in front of Njideka Akunyili Crosby

Predecessors (2013) at Tate Modern, 2023 Photo © Tate

Artist Marie Smith and the Tate Interpretation team held a workshop in the Tate Modern exhibition Capturing the Moment. A group of Tate staff and friends were invited to relate to artworks in sensory and counterintuitive ways.

You are invited to listen to their conversations below. Take the insights that arise and run with them. What can you see and sense? What frequencies can you tune into?

You’ll hear the voices of Marie, Melba, Vasundhara, Hannah, Toni, Deborah, Elliott, Jelena, Alessia, Sofia, Tanya, Hannah, and Stary.

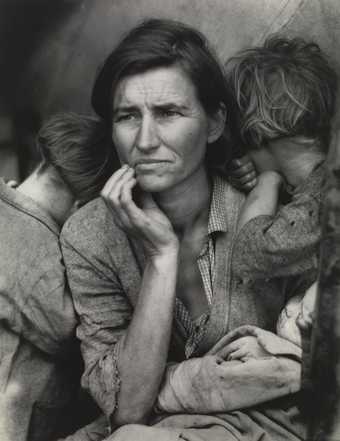

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California

Dorothea Lange

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936, printed c.1950)

Tate

Lange took this photograph in the 1930s while working for a US government agency called the Resettlement Administration (RA). The RA wanted to demonstrate the hardship suffered by impoverished White US farm workers to raise public support for their work and the policies of President Roosevelt’s administration. This led to practices such as naming photographs after the ‘type’ of person featured in them, rather than the individual sitter. Migrant Mother is a very famous example and was soon reproduced in newspapers across the country as the defining photograph of the US Great Depression.

When the sitter Florence Owens Thompson was later identified in 1978, she stated: ‘I wish she hadn’t taken my picture … [Lange] didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.’ It was also revealed that Thompson was of Cherokee heritage, while the RA had historically overlooked the plight of Indigenous North American people. Looking at the portrait today allows us to question the ethics of photographic representation, and what happens when an individual is made to stand in for a multitude.

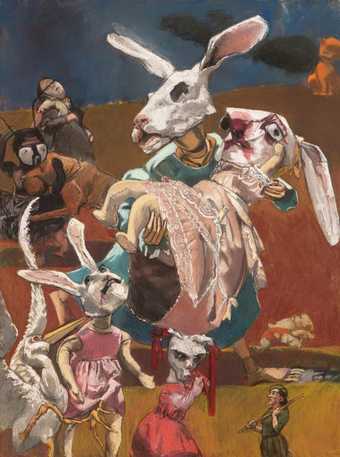

War

Paula Rego

War (2003)

Tate

War is based on a newspaper photograph of Iraqi civilians in the aftermath of a bomb explosion during the Iraq War. Rego was shaken by the image of a mother carrying a baby, seemingly frozen in fear, and a girl screaming next to them. Here, she gives the figures mask-like rabbit heads. A disfigured children’s toy on the ground makes the horror more intense. As in Rego’s other work, the figures reference the subversive and psychologically troubling traditions of folk and fairy tales which explore themes of violence and sexuality.

A Sudden Gust of Wind

Jeff Wall

A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) (1993)

Tate

Jeff Wall's work explores the boundary between truth and fiction, everyday life and fantasy, challenging the traditional notion that photography faithfully records reality. A Sudden Gust of Wind captures what seems like an instant frozen in time. It depicts four figures caught in a sudden gust that has swept across the open landscape. The photograph is, however, meticulously staged. The composition is based on a woodcut by Japanese painter and printmaker Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), and it took Wall over a year and more than a hundred separate shots to complete.

Musée du Louvre

Thomas Struth

Musée du Louvre, Paris (1989)

YAGEO Foundation Collection, Taiwan

© Thomas Struth

In Musée du Louvre, Struth depicts visitors viewing The Raft of the Medusa 1818–9 by French Romantic painter Théodore Géricault (1791–1824). Struth’s museum photographs invite us to consider how Western historical artworks are collectively experienced in museums, churches and palaces. Struth has been described as an ‘objective’ photographer, one who faithfully records reality. However, by portraying the behaviour of people in the act of looking, and the codes that underpin cultural institutions, Struth puts into question the neutrality of those spaces and viewpoints.

Tyrrhenian Sea, Conca

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Tyrrhenian Sea, Conca (1994)

YAGEO Foundation Collection, Taiwan

© Hiroshi Sugimoto

Sugimoto’s Seascapes capture the infinite: a universal image of the sea that has been encountered throughout generations. The series comprises 220 black-and-white photographs, developed over 30 years in different locations across the world. Somewhere between representation and abstraction, the works depict expansive views of the ocean against cloudless skies. They are punctured by a horizon line that dissects the compositions in half and delineates the limits of visual and mental perception.

The Seascapes convey the passing of time. Sugimoto refers to these works as ‘time exposed’, alluding to his technique of long exposure, where light gradually burns into the prints to produce an image. Unfolding endlessly beyond the horizon, Sugimoto's oceans position humanity in stark contrast to the vastness and persistence of nature. They ask us to reflect on the urgent need to protect our rapidly decaying planet, in Sugimoto’s words, to ‘think before destroying ourselves’.

Aunt Marianne

Gerhard Richter

Tante Marianne

Aunt Marianne (1965)

YAGEO Foundation Collection, Taiwan

© Gerhard Richter

Aunt Marianne was painted in 1965 from an everyday family snapshot, as part of a larger series of black and white photopaintings. It shows a four-month-old Richter with his young maternal aunt, who was later murdered by the Nazi eugenics programme in Dresden during the Second World War. The work has a hazy, smudged look, like a blurred frame from a film reel. By highlighting this photographic quality in paint Richter reminds us that the image may not be faithful – it is a copy of a copy. We are challenged to question whether images can ever capture objective truth.

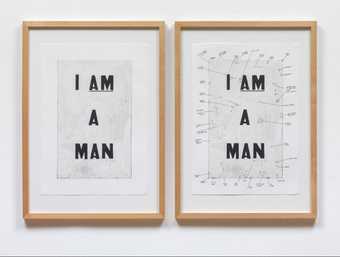

Predecessors

Njideka Akunyili Crosby

Predecessors (2013)

Tate

Akunyili Crosby creates her multi-layered work from family photographs and personal memorabilia mixed with cutouts from Nigerian popular magazines and newspapers. These disparate items reveal the multiple sources of influence on people’s experiences in our contemporary multi-cultural world. The female figure is the artist’s alter ego, a modern African woman who embodies a cosmopolitan African lifestyle. Akunyili Crosby refers to her as an ‘Afropolitan’, representative of a new generation of Africans who exist between multiple geographies and cultures, living a trans-cultural and trans-national life.

The Promised Land

Michael Armitage

The Promised Land (2019)

Tate

The Promised Land reflects on political demonstrations that followed the 2017 general election in Kenya. At least 45 people died disputing the elections outcome. The painting draws together media narratives with Armitage’s own views on contemporary Kenya. On the left, the banner held by a protester references the nude in European art history, connecting political ideas with aesthetic tastes. On the right, people’s bodies are transformed by encroaching tear gas. The work is painted on Lubugo, a bark cloth which is culturally significant for the Baganda people in Uganda, traditionally used as a burial shroud.

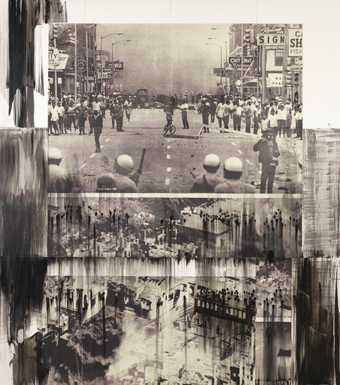

Then & Now

Lorna Simpson

Then & Now (2016)

Tate

Then & Now was made by screenprinting found photographic imagery onto clayboard panels, with black ink added by hand. The work appropriates an iconic photograph taken during clashes between Black residents and police in Detroit in 1967. The title suggests a dialogue between past and present, connecting the events of 1967 to the present where police brutality and disproportionate violence towards Black citizens continues. Masking the photographic imagery beneath, the black ink dramatises the violence of the event, while the fragmentation of the images mirrors the complexity of the narrative being represented.