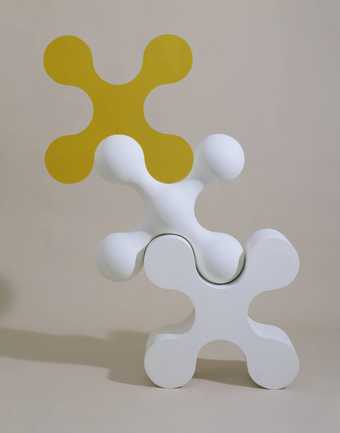

William Tucker

Anabasis I (1964)

Tate

William Tucker occupies an important position in the history of late twentieth century sculpture. His investigation into the nature of sculpture and its relationship to the viewer has led him to use a range of processes and materials. In the early 1960s he played a vital role in changing the face of British sculpture through his experimentation with abstraction and construction. During this time he wrote extensively on sculpture. He moved to the USA in the late 1970s, where he continued to make abstract constructions in wood and steel; since the early 1980s he has modelled directly in plaster for casting into bronze. His return to the representation of the figure reaffirms him as one of the most challenging and enquiring artists of his generation. This display brings together early works from Tate Collection and more recent sculpture from private collections.

William Tucker studied History at Oxford between 1955 and 1958. During these years, he attended life-drawing classes at the Ruskin School of Drawing. Encouraged by fellow students there, such as RB Kitaj, he began to take an active interest in contemporary art. A visit to the Holland Park sculpture exhibition in 1957 led to his first attempt at sculpture, and he subsequently studied sculpture at the Central and St Martins Schools of Art from 1959 to 1961. The late 1950s and early 1960s were a period of great excitement for young artists in London, largely inspired by a series of exhibitions of American painting, not only of the work of the leading Abstract Expressionists, but of younger artists such as AI Held and Jasper Johns.

Although the liberating effect of American abstraction was more direct on painting, it was also influential on Tucker and his contemporaries. In their move away from the figuration of Henry Moore and his followers they looked to European modernism, as well as the work of American sculptors such as David Smith, to guide them towards a new abstraction in sculpture. When Tucker arrived at St Martin's the sculpture department was attracting students from all over the world, under the dynamic leadership of Frank Martin.

In the early 1980s Tucker turned to modelling, a process he had strongly rejected. Working in America, a place with little or no tradition of carving and modelling, made him 'aware of what Modernism had left out', and he was encouraged to look afresh at this now unfashionable tradition. For an artist once adamant that the human image had been 'contaminated by what I perceived as the facile and rhetorical posturing of the followers of Rodin', it seemed paradoxical that he should turn to the figure and indeed to Rodin, for inspiration. Tucker remarked that modelling was 'the most direct way of understanding the human body, but not from outside, from the observed contours of the model's body, but from within, from the consciousness of being one's own body'. Plaster provided Tucker with the ideal modelling material because its quick setting properties allowed the spontaneity of the artist's hand to be captured.

Though despite the seemingly radical change in Tucker's practice, this display traces the development of his work from the 'prolonged anatomy lesson' of construction to its natural conclusion in modelling.