Lucian Freud

Woman with an Arm Tattoo (1996)

Tate

INTRODUCTION

I've always wanted to create drama in my pictures, which is why I paint people. It's people who have brought drama to pictures from the beginning. The simplest human gestures tell stories. – Lucian Freud

German-born artist Lucian Freud (1922–2011) was among the leading figurative painters of the twentieth century. Throughout his seventy-year career, Freud mantained a life-long interest in the human face and body and relentlessly explored the possibilities of portraiture. His work was deeply rooted in the continuous and uncompromising observation of any individual who posed for him. Always painting from life, Freud was drawn to people he was familiar with, like family and friends. His works often recorded the cycles and transformations of his relationships. He expected a significant commitment from his sitters, requiring them to pose for several hours at a time, over a period of weeks or months, and in some cases even years. Freud also regularly turned his gaze inward, applying the same unsparing level of scrutiny to his self-portraits. His works demonstrate the unrelenting intensity of his observation and his deep commitment in revealing the sense of individuality in each person, animal or object.

A deeply private and guarded person, it is through his work that we get to know Freud the man. The exhibition explores the different aspects of his practice alongside his complex relationships with some of the people who modelled for him. Lucian Freud: Real Lives spans seven decades, from Freud’s early explorations of the self-portrait up to his large nudes completed in the last twenty years of his life.

Lucian Freud: Real Lives is curated by Laura Bruni, Assistant Curator, Tate Liverpool

Early Works

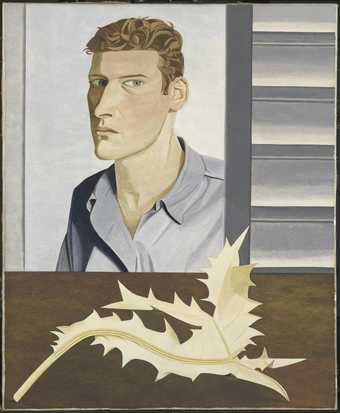

Lucian Freud

Man with a Thistle (Self-Portrait) (1946)

Tate

Learn more about Freud’s work with our free audio guide. Tate conservators Rachel Scott and Natasha Trenwith explore the techniques and materials in Freud’s paintings and etchings.

Freud’s first subjects included himself, his friends and neighbours, and a handful of still life compositions. In his early works, Freud painted while seated at close proximity to his subjects, paying an almost forensic attention to every detail, capturing everything from the subtle tonalities of flesh to individual locks of hair. The works from this period were usually psychologically charged portraits, demonstrating a distinctive vision and linear approach. In 1956, Freud adopted a standing position which he maintained for the rest of his career. This shift in position resulted in high viewpoints that often emphasised the voluminous presence of a body. Freud also began to paint full figures and naked portraits more regularly.

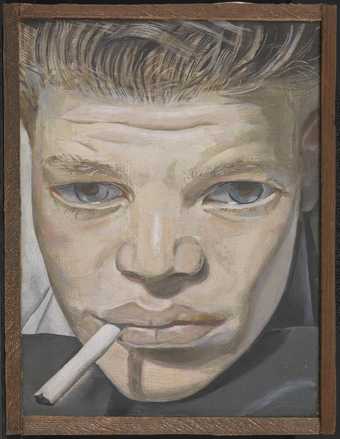

Charlie Lumley

Lucian Freud

Boy Smoking (1950–1)

Tate

In 1944, towards the end of the Second World War, Freud moved into a flat on Delamere Terrace in Paddington. The Lumley family lived next door, including fourteen-year-old Charlie. The Lumley’s considered Freud to be rich, as he lived alone, while they – a family of seven – shared one flat. Recounting how they met, Freud commented that Charlie ‘wandered along the balconies, along the terrace, into my room. There was one of these bombing raids and then he suddenly seemed to sort of belong to me.’

The two became close friends. Charlie showed Freud the local nightlife, while Freud often helped Charlie when he ran into trouble with the law. Freud enjoyed going out with Charlie, ‘especially clubs where Charlie’s friends met. Charlie was good with girls. I used to envy him’. Charlie regularly posed for works, including Boy Smoking 1950–1 and Narcissus 1948. This continued until 1960, when the two men lost touch following Charlie’s wedding.

Kitty Garman

Kitty Garman, the daughter of sculptor Jacob Epstein and Kathleen Garman, was Freud’s first wife. The pair married in 1948, when Kitty was heavily pregnant with their first daughter, Annie. They went on to have another daughter, Annabel, before splitting up in 1952. Domestic life was challenging for Freud, he struggled with sharing his space and losing his privacy. Infidelity was also constant, Annie commented that ‘Dad was spectacularly unfaithful’ to Kitty throughout their marriage.

While they were together, Kitty was a frequent model for Freud, and his evolving style can be seen in these works. Girl with a Kitten 1947 shows the muted colours and precise lines of his early work. Whereas Girl with a White Dog 1950–1 includes many of the elements Freud is best known for, such as nudity and an attentive focus on the different colours and tones of human skin. Girl with a White Dog also shows Kitty’s growing confidence in herself, and Annie recalls that ‘My mother was very very proud of this painting.’

Bella Freud and Kai Boyt

Bella Freud is the daughter of Lucian Freud and Bernadine Coverly. Freud and Coverly’s relationship began when she was around seventeen years old, and she soon fell pregnant with Bella, who was born in 1961. Freud was a distant father to Bella and her sister Esther, as well as his other acknowledged children, preferring to get involved once they were old enough to hold a conversation and pose for him. Bella enjoyed posing for her father, and the two of them eventually built a close relationship. She would cut his hair and give advice on food and healthcare. In the early 1990s, when Bella was starting her fashion label, Freud provided crucial financial support.

Freud was also close with Kai Boyt, the son of Suzy Boyt. Freud met Suzy at the Slade School of Fine Art when he was her tutor. She was considered a promising painter but did not continue after falling pregnant with her first child with Freud. Suzy had four children with Freud: Alexander, Isobel, Rose, and Susie. While Kai was not his son, Freud considered him as one. Kai often helped out around the house and studio, and regularly posed for Freud. In 2011, when Freud died, Kai was at his side.

Celia Paul

Lucian Freud

Girl in a Striped Nightshirt (1983–5)

Tate

In 1978, Freud was invited to be a visiting tutor at the Slade School of Fine Art, where he met eighteen-year-old painter Celia Paul. According to Paul, ‘Lucian said that he had come to the Slade to find a girl, and that girl was me.’ Freud quickly initiated a romantic relationship, inviting Paul to his home studio on the first day that they met. They remained together for ten years, and their son Frank was born in 1984.

Early on in their relationship, Paul had no way of contacting Freud, saying ‘Lucian hadn’t given me his phone number, so I often spent days in my room, too afraid to go out in case I missed his call.’ Paul was also aware of Freud’s other affairs, which were a popular subject of gossip among her fellow students.

Freud often asked Paul to pose for him, and this provided mixed experiences. She was pregnant while modelling for Girl in a Striped Nightshirt 1983–5, and the painting became a favourite of Paul’s, as she found Freud particularly loving and attentive during this time. However, she was uncomfortable posing nude, saying that in one sitting Freud ‘stood very close to me and peered down at me. I was very conscious of my flesh, and I felt myself to be undesirable.’

Lucian Freud

Head of a Woman (1982)

Tate

Lucie Freud

Lucian Freud

The Painter’s Mother (1982)

Tate

Freud had a complicated relationship with his mother, Lucie. Growing up, he was her favourite, which caused tension between Freud and his brothers. In response to this, he pulled away, saying ‘I certainly didn’t like my own mother as she was so affectionately, insistently, maternal. And because she preferred me: if it had been equal I wouldn’t have minded.’

This changed after Freud’s father, Ernst, died in 1970. Before this, Freud avoided spending time with his mother and she only posed for him on rare occasions. Ernst’s death heavily impacted on Lucie, and she went into a deep depression, becoming a much more subdued person. From this point she became one of Freud’s most consistent models, posing over a thousand times from 1972 until her death in 1989. These portraits are ultimately a study of aging, documenting the artist’s mother as she approached the end of her life.

The two developed a regular routine of breakfast at Maison Sagne’s in Marylebone High Street, followed by four-hour sittings for works such as The Painter’s Mother IV 1973. Commenting on his and Lucie’s changing relationship, Freud remarked that ‘If my father hadn’t died I’d never have painted her. I started working from her because she lost interest in me; I couldn’t have if she had been interested.’

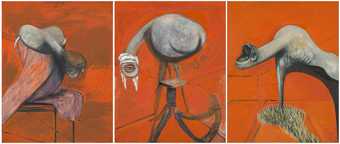

Self-portraits

Freud painted a self-portrait for every significant milestone in his life but destroyed the majority of them. Therefore, those that remain reveal how central they were to the development of his work. Freud painted his first major self-portrait in 1943 and went on to create many more. From the beginning he worked with a mirror, as opposed to photographs, which were preferred by his friend and fellow painter Francis Bacon. Freud would often leave mirrors around in his studio to find unexpected angles and perspectives. A number of drawings – including Narcissus 1948 on display nearby – show him experimenting in this way.

His use of a mirror also brings a sense of confrontation. Many of Freud’s sitters look away from the viewer and appear lost in their own thoughts. However, in his self-portraits Freud always looks directly at the mirror, and by extension the viewer. As art critic Sebastian Smee points out, Freud seems almost to be spying on himself ‘as if he were trying to catch his own reflection unawares. His expression is suspicious, challenging, sceptical. In others, his gaze is direct, frontal, unswerving.’

Freud's Studio

In the late 1970s Freud moved into a spacious, top-floor flat in West London. This was Freud’s first proper studio; he installed a skylight so that he could paint indoors in much brighter daylight than before. Once a painting began during daylight, he continued the sittings during daytime. Likewise, if a painting was started at night-time, he continued the sittings at night, using very high wattage light bulbs. Freud would work on several paintings concurrently, and the day and night pictures were never swapped. At night, the large electric lights would cast strong shadows. Sitters would come and go but were always kept separate from each other. They were well taken care of with gossip, poetry and good food. In return they had to be punctual and have, as Freud put it, ‘an inner life that’s ticking away’ to occupy themselves while he painted.

Characteristically for Freud’s work from the 1960s until his death in 2011, the studio was not only the site of production, but also the subject of the work itself. Human figures dominate most of Freud’s work, yet painting tools and furniture are also important elements of the compositions. Plants, in particular, played an important role in Freud’s practice. He often turned to them when his style was evolving or when his personal relationships were strained.

David Dawson’s photographs provide an intimate insight into a workplace that Freud kept secret, protected from unexpected visits. The images show us Freud’s work in progress, within the simple, sparsely furnished space he preferred.

Lucian Freud

David and Eli (2003–4)

Lent from the Schroeder Collection courtesy of the Faurschou Foundation 2014

Lucian Freud

Two Plants (1977–80)

Tate

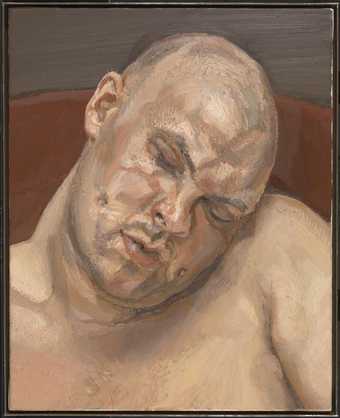

Leigh Bowery

Lucian Freud

Leigh Bowery (1991)

Tate

From 1990 until his death in 1994, Leigh Bowery was a regular model for Freud. Bowery was an Australian artist, club promoter and fashion designer, known for his elaborate costumes and controversial performances. Freud had seen Bowery perform in the late 1980s, developing a fascination with his physical presence, commenting that the way Bowery ‘edits his body is amazingly aware and amazingly abandoned.’

The two men quickly settled into a routine, sometimes working together five or six days a week, with Bowery posing for several hours at a time. Notably, Bowery appears nude throughout these works, free from the flamboyant costumes and make up that he was known for. Bowery enjoyed sitting for Freud, saying that it was ‘Nice having that level of attention, and a tension. The bonus is the quietness. You get a different sense of yourself.’ The experience was equally rewarding for Freud, he said of Bowery that ‘Someone who wasn’t a dancer couldn’t move and relax as he does. I’ve increasingly tried to get movement into my figures and he’s helped me very much.’

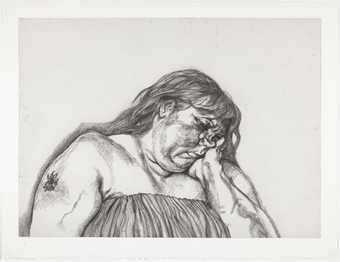

Sue Tilley

Sue Tilley, known as ‘Big Sue’, was a friend of Leigh Bowery’s and worked at his nightclub, Taboo. It was through Bowery that she was introduced to Freud, and she modelled for him on several occasions in the mid-1990s. Tilley was initially apprehensive about posing nude, saying that she ‘used to get a bit embarrassed’ and that ‘Leigh made me take my clothes off to practise’.

Freud did not have a sexual relationship with Tilley, but he nonetheless developed a brief artistic infatuation with her. He said that he’d become ‘aware of all kinds of spectacular things to do with her size. Like amazing craters and things one’s never seen before, my eye was naturally drawn round to the sores made by weight and heat.’ However, Freud ultimately moved on, feeling that he was limiting himself by focusing too much on Tilley.

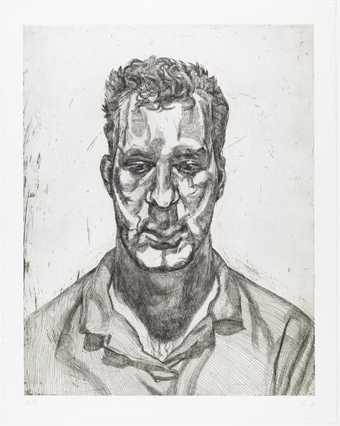

Nudes

Freud began focusing on full-length nudes from the mid-1960s onwards. From the 1980s onwards, he began producing larger and larger nudes, all staged within the confines of his studio. Standing by the Rags 1988–9 provides a notable example, showing the physicality of Freud’s work at this time, with the model’s body rendered in particularly thick layers of paint. Freud liked his sitters to find their own poses, often using the first few modelling sessions to try different options and find something suitable for the painting, but comfortable to maintain for hours at a time. Although his paintings show equal attention to inanimate objects – rags, furniture, plants – his etchings omit backgrounds entirely, focusing completely on the physical presence of the sitter.

A painter and draughtman of striking, sometimes disquieting, male and female nudes, Freud preferred to describe them as ‘Naked Portraits’. Rather than showing idealised bodies, his nudes are a frank scrutiny of the human form, ultimately revealing the universal nakedness of his subjects.

Humans and Animals

Animals, especially dogs, appear in many of Freud’s works. They could be portrait subjects in their own right, such as Pluto 1988, or in combination with people, as in Double Portrait 1985–6. Double Portrait shows Freud’s friend Susanna with her dog, Joshua, and their bodies share the same patterns. In his etchings and paintings featuring animals, Freud applied the same level of intense scrutiny and treatment both to the animals and human subjects and they are painted as equals.

In his final in his final years, the painter David Dawson was Freud’s regular model and companion, as well as his assistant from 1990 up until his death. Dawson was often painted alongside his whippet, Eli, showing Freud’s interest in the complicity of humans and animals. Freud has said that ‘I am really interested in people as animals. Part of my liking to work from them naked is for that reason.’

The audio guide was produced by David Clack. With thanks to David Dawson and William Feaver. Voiceover and research by Rachel Scott, Paintings Conservator, and Natasha Trenwith, Paper Conservator