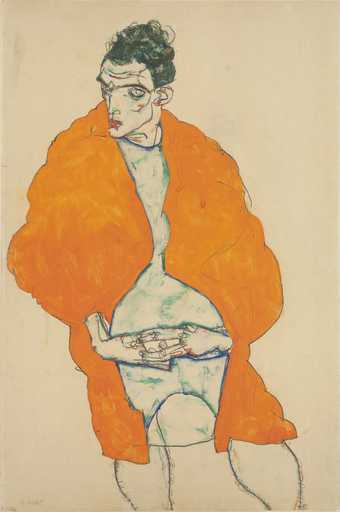

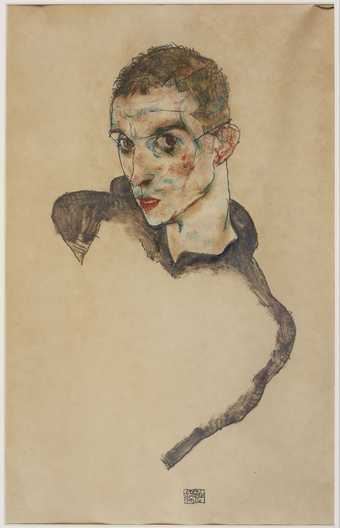

Egon Schiele, Standing Male Figure (Self-Portrait) 1914.

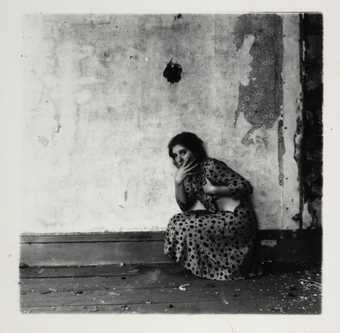

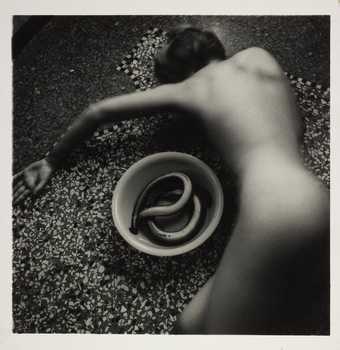

Francesca Woodman

Untitled, from Polka Dots Series, Providence, Rhode Island (1976)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© Woodman Family Foundation / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

Life in Motion brings together works by renowned expressionist artist Egon Schiele and photographer Francesca Woodman. The exhibition highlights and interrogates the instability of identity, the transitional nature of psychological states and the expression of this through dynamic bodily movement. The artists' works explore moments and passages of time, revealing the quick, intuitive mark-making of Schiele, and the technical flair of Woodman's compositions.

The precocious ability of Egon Schiele (1890–1918) was nurtured by Gustav Klimt, Vienna's leading artist. Although Schiele initially drew great inspiration from his mentor, he quickly developed his own distinctive style. A master draughtsman, he is known for his erotic depictions of women and himself. He depicted his subjects in unconventional poses, with expressive faces – ranging from anguished to climactic – and with an emphasis on the hands, which were often greatly exaggerated. When he died of the Spanish flu, he was among Austria's leading artists.

Francesca Woodman (1958–1981) grew up in an art-loving family, taking up photography aged 13. Showing unusual aptitude, she became interested in interactions of the body within space, depicting herself merging with her surroundings, or employing a long camera exposure to appear as a blur, suggesting bodily presence as fleeting or uncertain. Dedicated and prolific, she once said: 'I have a lot of ideas cooking, simply need to get started working before they stick to the bottom of the pan.'

Presenting Schiele and Woodman together for the first time on this scale, Life in Motion explores their enduring relevance, showing how these sublimely innovative artists connect across time and medium.

Egon Schiele

1908–1910

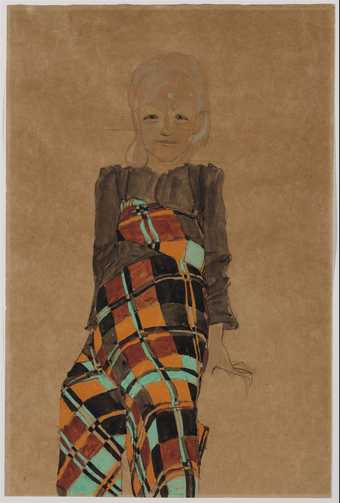

Egon Schiele, Seated Girl 1910. © Szépművészeti Múzeum / Museum of Fine Arts Budapest, 2017.

Egon Schiele was born on 12 June 1890 and lived in Vienna with his parents and two sisters, Melanie and Gertie. His father Adolf succumbed to syphilis when the artist was 14 years old, which had a significant impact on his depictions of both parenthood and sexuality. After his father’s death, Schiele’s uncle Leopold Czihaczek, took on guardianship of the boy and financed his attendance at the Academy of Art in Vienna where at 16 he was the youngest pupil in his class. Schiele found the Academy’s approach old fashioned and sought the advice of Gustav Klimt, one of the leading expressionist artists of the time, who became his mentor and continued to support the young artist throughout his career.

In 1909 Klimt invited Schiele to take part in the ‘Kunstschau’. This was the second iteration of an exhibition conceived by a number of artists who advocated for the freedom of art from traditional conventions. Here he exhibited four works alongside established names such as Munch, Matisse and van Gogh.

Throughout 1908 and 1909 Schiele’s work clearly emulated the style of his mentor depicting elongated bodies cloaked in long drapery. However, from 1910 he swiftly developed his own distinct style, creating works in an expressionist manner using quick, sharp lines, favouring blank backgrounds as opposed to Klimt’s more decorative approach. Throughout his brief career, Schiele experimented with colour using both watercolour and gouache, and rendered his figures in an increasingly defined three-dimensional manner.

1911–1913

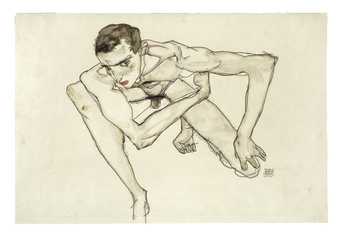

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait in Crouching Position 1913. Photo: Moderna Museet / Stockholm

From an early age, Schiele had a fascination for the human body, primarily depicting female models in often revealing, erotic poses. In the early 20th century, Viennese society was conservative and the artist’s works were frequently criticised and labelled as pornographic. However, he felt that obscene readings of his works were down to the viewer, and stated: ‘I do not deny that I have made drawings and watercolours of an erotic nature. But they are always works of art. Are there no artists who have done erotic pictures?’

Despite being best known for such depictions, Schiele’s practice was much more varied, including more formal portraits, landscapes, and many self-portraits. Having dropped out of the Academy in 1909, followed by the subsequent withdrawal of financial support from his uncle, Schiele struggled to make ends meet. Unable to afford to hire models, the artist created many self-portraits using a mirror to draw himself. Schiele also often featured children in his work; relatives and family friends as well as street children. He was interested in what he saw as their unbridled energy, having not yet been influenced by societal pressures. But living in Neulengbach, a small town west of Vienna, the artist was arrested for abducting and seducing a minor. These charges were dropped but Schiele was prosecuted for public immorality, as his young models would have been exposed to images in his studio deemed indecent at that time.

Returning to Vienna in 1913, Schiele largely stopped drawing children, while his portrayal of female models changed too; in these later works women are depicted with averted faces rather than making direct eye contact with the artist and the viewer, often concealing their identity. One model who appeared frequently in Schiele’s work of this period is Walburga (Wally) Neuzil. It is thought that Wally was introduced to the artist by Klimt, for whom she had supposedly been posing nude, and the two developed an intimate relationship.

1914 – 1916

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait 1914.

Although perceived as controversial, Schiele and his work slowly began to gain recognition; progress, however, remained slow. In 1913, his first international solo exhibition took place in Munich, organised by dealer Hans Goltz, who ended their relationship due to a lack of commercial success. Schiele’s second Viennese solo exhibition took place in the following year. It was around this time that the artist’s work started to mature, his subjects being drawn with greater certainty, finding a balance between more realistic physicality, the capturing of movement and state of mind.

In his personal life too, Schiele made significant changes. In 1914 he met Edith Harms who lived nearby the artist’s studio in Vienna. Despite disapproval from the Harms family, the artist married Edith the following year. Though Schiele intended to maintain a relationship with Wally, proposing a yearly vacation together, she immediately rejected this idea and they did not see each other again. On 20 June 1915, three days after his wedding to Edith, he was conscripted into the army, the First World War having broken out the previous year. Though he never saw action, his time in the army led to a decline in artistic output. Initially stationed in Prague, the couple returned to Vienna in January 1917 when he was assigned to the Imperial and Royal Military Supply Depot, and life largely returned to normal.

1917–1918

Upon his return to Vienna, Schiele’s artistic production increased significantly. By 1917 he was becoming increasingly commercially successful receiving private commissions for more formal portraits. His earlier style favoured the use of pencil to create sharp, angular lines to depict emaciated, tortured figures. Towards the end of his career this was replaced by rounded lines rendered in black crayon, suggesting a larger degree of volume and more realistic representation of his models. Despite the financial benefits that came with formal portraits, Schiele stayed true to his interest in the expressive nature of the human body and continued to create explicit drawings.

During this time the artist also explored other professional avenues, proposing a Vienna Kunsthalle with the support of Klimt, composer Arnold Schönberg, and architect Josef Hoffmann, who co-founded the Wiener Werkstätte, a group that aimed to integrate art and design into everyday life. Despite funding for a building being secured, the plans ultimately failed. Klimt died aged 55 in February of 1918, while his former protégé Schiele rose to prominence. The following month he organised the 49th exhibition of the Vienna Secession, a radical group of artists who had broken away from the traditionalism of the previous generation (of which he had become a member the previous October). An indication of his standing and confidence, he set aside the central room for a large presentation of 50 of his own works.

Having already claimed the life of Klimt and killing an estimated 50 million people world-wide, later that year the Spanish flu ruthlessly took its toll on the Schiele family. Edith, six months pregnant with the couple’s first child, succumbed to the disease on 28 October 1918, while Egon died three days later at just 28 years of age. Deeply innovative, Schiele left a profound legacy, influencing his peers in the Austrian expressionist movement, and subsequent generations of artists alike.

Francesca Woodman

Section one

Francesca Woodman

Space², Providence, Rhode Island (1976)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© Woodman Family Foundation / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

Francesca Woodman was born in Denver, Colorado, on 3 April 1958. Her parents, George and Betty, taught at the University of Colorado and were both artists – a painter and a ceramicist, respectively. Art was a way of life in the Woodman household, and Francesca and her older brother Charles were exposed to creativity from an early age. On their regular visits to galleries and museums, they were always given sketchbooks, and encouraged to draw what they saw and develop their talent.

The family often travelled to Italy during Woodman’s teenage years, living in Florence for a year in 1965. In 1968, her parents bought a farmhouse in nearby Antella, where they spent their summers. Italy became a long-term source of inspiration for Woodman, her work often referring to aspects of the classical art that she was exposed to during her childhood, in-particular the nude, and its status as a longstanding symbol in art history.

Woodman became interested in photography in high school and received a camera from her father aged 13, which she continued to use throughout her career. Best known for her black and white photographs, her work often features the human body merging with its surroundings, becoming blurred due to movement during long exposure times. Woodman often depicted herself as both subject and object in her work, addressing concepts of self, gender, body image and identity.

Section two

In 1975, aged 17, Woodman moved to Providence to study at the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design. Among the oldest art schools in the United States, innovative photographers such as Aaron Siskind taught Woodman during her time there. During her studies, she used an old unheated studio where she explored and developed her practice.

Between 1977 and 78, after gaining a scholarship from RISD, Woodman spent a year in Rome as part of a student exchange programme. Her experiences in the city proved formative, soaking up influences ranging from classical to surrealist art. Along with fellow artists, she occupied an abandoned spaghetti factory which they used as a studio. She frequently visited the small Libreria Maldoror bookshop and gallery, which specialised in surrealist and other avant-garde writing. The Maldoror went on to host the first exhibition of her photographs in 1978.

During this period, she embarked on a sequence of photographs known as the Angel Series. In some of these works, she takes on the form of the ‘angel’, making wings out of white sheets, while in others the human figure appears shadow-like as if in the process of disappearing. The series evokes spectral figures and states of transition, and Woodman’s body features as delicate and ethereal. Photography and its ability to capture extended moments in time interested her, and she saw it as a medium through which she could reveal hidden energies within the body.

Section Three

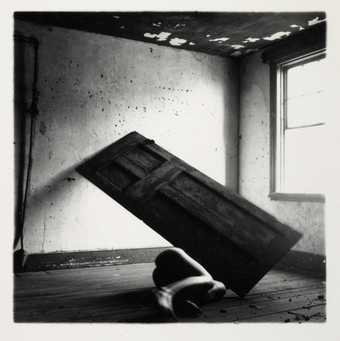

Francesca Woodman

Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island (1976)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

© Woodman Family Foundation / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

A recurrent theme in Woodman’s work is her use of props to dress, embellish and obscure the body. She frequently conceals the faces of herself and her other models, and obscures parts of the body behind furniture, wallpaper or plants. Often the figure disappears, subsumed by architecture or merging with the various objects she carefully selected. Mirrors, books, velvet chairs and even unhinged doors are employed, adding to the performative and mysteriously eccentric aspects of her compositions.

Woodman was adept at staging, directing, and acting in her photographs. Exploring the body’s relationship to architecture amid crumbling, and otherwise disused settings, she imbued in these works her flair for decay and romantic bohemia inspired by gothic 19th century literature. As noted by one of her friends, the artist ‘seemed to have been born in the wrong century’, a trait demonstrated in many of her works. Often devoid of modern objects, and with Woodman dressed in vintage clothing, they appear to belong to another age than those in which they were taken.

Woodman also uses more contemporary materials and props, such as Sellotape and clothes pegs, where they are employed as a means of experimenting with, and distorting the body’s pliant physicality. Intervening in her body’s symmetry, she tests how the human form inhabits spaces using herself as subject, enclosing herself within display cabinets and pressing glass against her naked form.

Section four

In 1979 Woodman moved to New York City, punctuated in 1980 with a month spent at the MacDowell Colony, in Peterborough, New Hampshire, the oldest artist colony in the US. While there, she worked on a series of photographs exploring the relationship between nature and her body. In this work, Woodman poses with taxidermied animals and uses bark from surrounding trees as sheaths for her arms, blending in with her surroundings. Her brother Charles has described it as ‘an attempt to come to grab the landscape at MacDowell’.

Interested in and inspired by fashion photography, Woodman hoped to earn an income in this field, and she sent her work to fashion publications and photographers, although she got little response. Over the course of the next year, she exhibited at several small galleries and introduced new techniques into her work, including colour photography and printmaking, with which she experimented on a monumental scale. Tragically, any further experimentations were abruptly cut short when she took her own life, aged just 22, on 19 January 1981.

From 1986, exhibitions of Woodman’s work began to appear, drawing a great deal of attention and acclaim. This ‘re-discovery’ of her work was accompanied by many different readings, including those from feminist theory. Although aware of this discourse, Woodman, approached female sexuality from a personal, rather than political point of view. Her photography has had a profound impact; her influence can be seen in the work of many contemporary artists, and her distinctive style continues to inspire the world of visual culture.