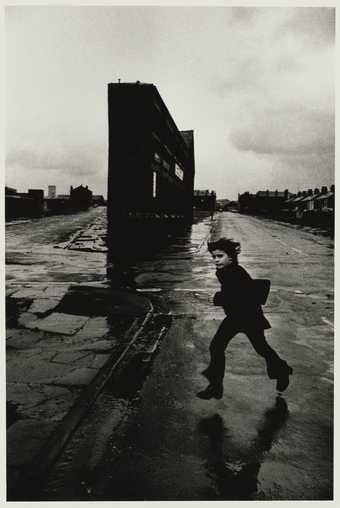

Don McCullin Consett, County Durham 1976 © Don McCullin

Introduction

What I hoped I had captured in my pictures was an enduring image that would imprint itself on the world’s memory.

Don McCullin

For over sixty years, Don McCullin has been continuously working both at home and abroad. It began in 1959, when a bold young McCullin strolled into the offices of the Observer with his photograph of London gang ‘The Guvnors’. His instinctive ability with the camera and his nose for a story were immediately recognised. He walked out having sold his picture, and with a commission to take more.

McCullin became one of the world’s leading photographers of conflict. He has spent his life covering war, famine and displacement around the world. Much of this work was done for the Sunday Times, where he spent almost twenty years. His photographs raised awareness of atrocities as they were happening, but they also have a long-lasting influence, continuing to shape perceptions of historical events such as the Vietnam War or the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

McCullin is known for his empathetic approach, informed by his own challenging childhood. Often following his own initiative, he worked to shine a light on social injustices in the UK. This included photographing London’s homeless communities, as well as making many trips to Liverpool and across the north, documenting the harsh living conditions for those dealing with deindustrialisation and poverty.

Unusually for an exhibition of contemporary photography, every photograph in this exhibition has been printed by McCullin himself. He is an expert printer, working in his darkroom at home, returning time and time again to produce the best possible results. In doing so, he revisits painful memories of his assignments; of people and places that are impossible to forget.

As a respite from conflict and suffering, McCullin has a longstanding interest in landscape photography. The surroundings of his home in Somerset are a subject he continues to return to, as a source of peace and comfort. Even here, the darkness makes its presence felt.

Titles

McCullin has always considered himself strictly a photographer, not an artist. As such, the titles of his images should be considered as photo captions. His intention is to provide necessary information, such as when and where an image was taken. At times, McCullin expands on this, giving an interpretation of events he witnessed first-hand, from his perspective as a Western journalist.

Photojournalism in the Gallery

When presented outside of the pages of print journalism, McCullin’s images are no longer consumed with the immediacy of ‘news’. Instead they become records of past events. In exhibiting these photographs, McCullin provides new audiences with evidence of some of the worst atrocities of the past sixty years. While acknowledging the difficulty of showing such subjects in a gallery setting, McCullin believes that ‘as newspapers won’t publish these images, they must have a life beyond my archive’.

Early Work

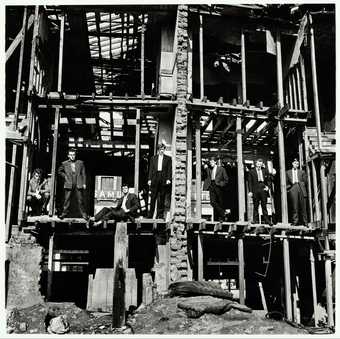

Don McCullin The Guvnors 1958 © Don McCullin

They published the photograph of the Guvnors a few weeks later and gave me fifty pounds, a king’s ransom to me… That was the beginnings of my humble roots in photography. Sadly this start was based on the death of a policeman and capital punishment for the man convicted. He was called Ronald Harwood and was hanged in Pentonville Prison, not far from Finsbury Park. The jumping-off point for my whole life was based on a terrible act of violence and its consequences.

Don McCullin

Don McCullin grew up in Finsbury Park in north London. At the time, the neighbourhood was still in partial ruins after being bombed in the Second World War. McCullin remembers a childhood of poverty, bigotry and violence. His father died of chronic illness when McCullin was fourteen. This affected him deeply and he was forced to leave school in order to work to support his family.

McCullin’s life was transformed by his first camera, a Rolleicord bought while on national service with the RAF in north Africa. On his return to the UK, McCullin was in need of money and pawned his camera. Luckily, his mother quickly bought it back. McCullin said that ‘What happened as a result of that generous act was to have a dramatic effect on my life.’

Berlin

Sir Don McCullin CBE

American Troops Looking across the Wall, Berlin (1961)

Tate

I came across a striking picture of Vopos (East German military) jumping over some barbed wire. It was the beginning of the Berlin crisis and the Wall. Suddenly I saw the direction in which my photography had to go. I said out loud: “I have absolutely GOT to go to Berlin.”

Don McCullin

In 1961 McCullin travelled to Germany to photograph the building of the Berlin Wall. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Germany was split into four zones, controlled by Britain, the US, France and the Soviet Union. The three western areas formed West Germany. The Soviet-controlled zone became East Germany. Berlin, located in the east, was similarly divided. The city, and the Wall in particular, became a striking symbol of the Cold War between the US, the Soviet Union and their respective allies, as both sides struggled for global supremacy. The fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 signalled the end of the conflict, and Germany was reunified less than a year later.

Although McCullin requested the assignment, the Observer was not initially interested in photos from Berlin. McCullin ultimately decided to pay for his own travel, a month’s earnings at the time. Upon arrival he went straight to the crossing point that would later become known as Checkpoint Charlie. This is where the tension was most palpable, with US forces facing off with East German and Soviet soldiers. The images he took capture the uneasy coexistence of military occupation and everyday life. McCullin’s photographs won him a British Press Award and a permanent contract with the Observer, who soon realised the historical significance of the images. From here on, McCullin became more confident in requesting assignments, and editors would learn to trust his instincts.

Cyprus

Cyprus left me with the beginnings of a self-knowledge, and the very beginning of what they call empathy. I found I was able to share other people’s emotional experiences, live with them silently, transmit them… That I had a powerful ability to communicate.

Don McCullin

In 1964 the Observer sent McCullin to Cyprus, where he had previously been stationed with the RAF during his national service, to cover the fresh outbreak of violence. The photographs he took were his first images of live conflict.

Cyprus is the site of a centuries-long, ongoing dispute between Greece and Turkey, and their respective ethnic groups living on the island. McCullin’s pictures document a period of fighting between the Greek and Turkish Cypriots that erupted in the aftermath of the island gaining its independence from British colonial rule in 1960. Britain and the US allegedly stoked this violence in order to maintain a strategically valuable military presence on British sovereign territory that remains in place today.

As an inexperienced newcomer, McCullin was excluded from the official RAF-led tour of the island. He, and another correspondent from the Observer, were ultimately left to their own devices. Driving around the city of Limassol, they found themselves in the midst of gun battle as 5,000 armed Greeks surrounded a small Turkish quarter. While other journalists were prevented from gaining access, McCullin was arrested and spent the night in the safety of a Turkish police cell and was able to document the panic on the streets the next day, after he was released. He credits his experiences in Cyprus for helping him to develop the powerful sense of empathy for which his images are known.

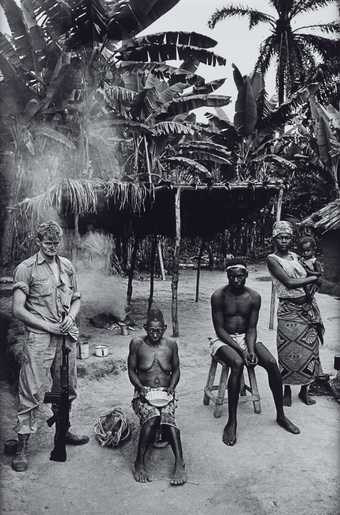

Congo

Sir Don McCullin CBE

Mercenary with Congolese Family, Paulus, Northern Congo (1965, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

I first went to the Congo in 1964… The fighting I encountered was vicious and cruel, and on the whole, evil men prevailed.

Don McCullin

In 1964 McCullin travelled to the Republic of Congo (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) working as a freelance photojournalist for the German magazine Quick. He was tasked with photographing the Simba rebellion in the east, which followed the 1961 murder of the country’s first independent prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. The assassination took place, allegedly with help from the US and Belgium, during a period of unrest following independence from Belgian colonial rule in 1960. During this time, the country felt the influence of the Cold War, as Lumumba and his followers had gained support from the Soviet Union, while the US wanted to prevent communism from spreading across central Africa.

Journalists had been banned from Stanleyville (now Kisangani), the Simba rebels’ base. To gain entry, McCullin disguised himself as a member of 5 Commando, a mercenary unit working for the Congolese government. Belgian paratroopers had reached the region earlier and McCullin was shocked by what he saw, describing it as ‘a most hideous large-scale set-up, with no rights or rules or immunities, with some of the most violent, cruel people in the world.’ When it was discovered that he was a photographer, McCullin was initially threatened with being handed over to the Congolese authorities. However, he was eventually allowed to join the troops on a rescue mission of missionaries and nuns who had been kidnapped by the Simbas. The rebels were ultimately defeated, but further instability followed, resulting in military dictator Mobutu Sese Seko leading the country from 1965 until 1997.

Biafra

Was I of any use at all to the Biafran people? Or was I simply aiding a war that was not in their interests, a secession generated by power-hungry zealots with no thought of the anguish and deprivation they left behind when they moved their weapons of destruction on?

Don McCullin

McCullin travelled to Biafra in 1968 and 1969 to photograph the humanitarian crisis caused by the Biafran War (now known as the Nigerian Civil War). The conflict was fought between the government of Nigeria and the separatist state of Biafra in the aftermath of Nigeria gaining independence from the UK in 1960. It was the result of the deep-rooted political, ethnic and religious tensions in Nigeria. These tensions originated in the 1914 British amalgamation of culturally and ethnically distinct areas into one centrally governed colony, forcing different groups into competition for resources and power. The 1966 massacres of Igbo people, the largest Biafran ethnic group, were further inciting events. A blockade set up by the Nigerian government meant that food and medical supplies were restricted, causing widespread famine and worsening disease. The federal Nigerian army has also been accused of the deliberate bombing of civilians, mass slaughter with machine guns, and rape.

Upon arrival in Port Harcourt, McCullin was immediately arrested by Biafran police. He was eventually released and allowed to go on a special mission with the army, who captured prisoners and executed them in front of McCullin. He refused to photograph the incident, not wanting to be complicit in killings that were staged for the media. The famine left a lasting impression on McCullin. On one outing he encountered 800 starving children in a Biafran school complex. His images, and those by other photographers, raised awareness of the situation. However, in December 1969, with increased support from the British government, Nigerian federal forces launched their final offensive. The Biafran state surrendered and was reintegrated into Nigeria in 1970. In three years of war, between 500,000 and 2 million civilians died, many of them children.

The East End

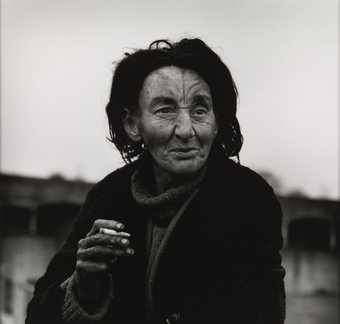

Sir Don McCullin CBE

Jean, Whitechapel, London (c.1980)

Tate

Many people send me letters in England saying “I want to be a war photographer,” and I say, go out into the community you live in. There’s wars going on out there, you don’t have to go halfway around the world… I don’t want to encourage people to think photography is only necessary through the tragedy of war.

Don McCullin

From the late 1960s to the early 1980s, McCullin photographed communities of men and women living on the streets of Aldgate and Whitechapel in east London. Located at the edge of the wealthy financial centre of the city, the area has since become unrecognisable due to extensive gentrification. McCullin believes that capitalism led to the closure of many unprofitable psychiatric institutions, leaving many of its residents homeless. He lamented the fact that the system works against people at the bottom of the social ladder who are unable to fight against its powers. To document this social crisis, McCullin set aside journalistic objectivity to work closely with the people he photographed. He took several images of a woman called Jean, and his study of her hands is both a testimony to the harsh reality of her living conditions and to McCullin’s connection to his subjects.

The North

Don McCullin Local Boys in Bradford 1972 Photo courtesy of Don McCullin

I wish I’d been born in Bradford, and had its beautiful dialect and its warm, relaxed attitude… Bradford’s full of energy and enthusiasm – an exciting, giant, visual city.

Don McCullin

McCullin was deeply affected by the trauma of reporting from some of the most violent conflicts of the second half of the twentieth century. When he returned home from these assignments, he often turned his attention to the tough lives of people in Britain. He photographed communities living in northern cities like Bradford and Liverpool, focusing on areas that had been neglected and left impoverished by policies of deindustrialisation. Often these trips were made on his own initiative, rather than being sent on assignment by a newspaper. McCullin saw similarities between their lives and his own childhood. Although he was ‘reporting’ on poverty and social crisis, he also identified deeply with his subjects, picturing the lives of others as a means of learning more about himself.

McCullin first visited Liverpool when he was fifteen years old, working on a steam train that travelled up from London three times a week. Later, as a young man, he returned as a photojournalist to document the changes that occurred in the city in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. This included the slum clearance that took place in Toxteth and surrounding areas, which gave the landscape the appearance of a warzone. Having grown up in similar circumstances, Liverpool felt familiar to McCullin and he became very fond of the city. Apart from photographing disadvantaged communities, he also spent time with artists and poets including Adrian Henri and Brian Patten for a 1967 Telegraph Magazine story written by Roger McGough, and documented the police for the Sunday Times in 1980.

Northern Ireland

Sir Don McCullin CBE

Catholic Youths Attacking British Soldiers in the Bogside of Londonderry (1971, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

I decided to... look more closely at conflict through civilian eyes. There was no need to travel the world to find what I wanted, for the situation was there on my own doorstep, in Northern Ireland.

Don McCullin

In 1971 the Sunday Times Magazine sent McCullin on one of many assignments to Northern Ireland. His photographs were published as part of a photo-story entitled ‘War on the Home Front’. They document a period of intense political violence during the thirty-year conflict known as the Troubles. The Troubles evolved out of almost one thousand years of British involvement and rule in Ireland. Despite the establishment of an independent Republic of Ireland in 1949, Northern Ireland remained a British territory and a site of conflict.

In the late 1960s, Catholic civil rights campaigns were met with police brutality. Subsequent unrest led to the deployment of the British army and an escalation of violence in the region. On one side of the resulting armed conflict were Catholic republican paramilitaries, such as the Provisional Irish Republic Army (IRA), who wanted Northern Ireland to be unified with the Republic of Ireland. They were opposed by Protestant unionist groups such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), who wanted the territory to remain part of the United Kingdom. British state security forces attempted to police the conflict, but covertly supported and colluded with unionist groups. The conflict was mostly fought on the streets, with violence often flaring up in residential areas where segregated Catholic and Protestant communities met. The conflict continued until 1998, when it was ended with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. However, political tensions and social divisions remain.

The situation left McCullin feeling torn. He empathised with the Catholic community, who often received him warmly. But he also felt he was betraying the British soldiers, who saw him as ‘consorting with the enemy’.

Magazines

McCullin’s work was most widely seen by the public in the Observer and the Sunday Times magazines. Prints, such as those featured here, have rarely been seen outside of gallery exhibitions. McCullin worked at the Sunday Times Magazine for eighteen years. The magazine accompanied the Sunday Times newspaper and was the first colour supplement to be published in the UK. From the early 1960s until the early 1980s, photographers like McCullin helped develop the magazine’s reputation for combining journalism with high-quality images.

This room shows some of these magazine spreads which include examples of McCullin’s colour photography, and stories not featured elsewhere in the exhibition. These magazine covers and articles provide a sense of how his work was originally seen, at Sunday morning breakfast tables across Britain.

Vietnam

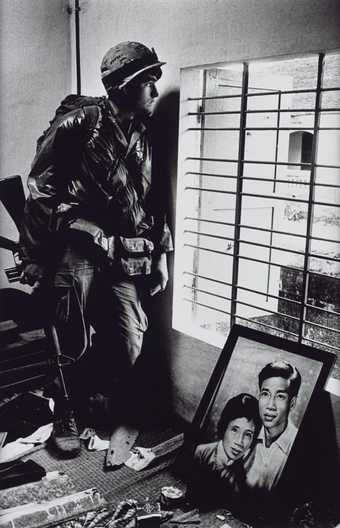

Sir Don McCullin CBE

The Battle for the City of Hue, South Vietnam, US Marine Inside Civilian House (1968, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Through sheer force of numbers and firepower, it seemed that the marines must eventually win, but at what cost? You could see that they were losing faith in the war. The swing of public opinion against the war at home in the States was also manifesting itself here in the front line as it was being fought.

Don McCullin

McCullin visited Vietnam sixteen times over the course of his career. Working on assignment for the Sunday Times he covered both the Vietnam War (also known as the American War) and its aftermath. The war was a protracted conflict running from 1954 to 1975. It pitted communist North Vietnam and the Viêt Công, their guerrilla allies in the South, against South Vietnam and their principal ally the US. The US and South Vietnamese forces relied on aerial warfare, including the use of the chemical weapon napalm, which resulted in many civilian deaths. It is estimated that between 1 and 3.8 million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians were killed during the conflict. 58,220 US service members also died.

In 1968 McCullin spent eleven days with US troops during the Battle of Hue. McCullin begged to be sent over on assignment and was approaching Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) just as North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive, a series of surprise attacks seizing southern territory, including Hue. McCullin took some of his best-known images as the Americans were fighting their way into the Hue citadel. Dressed in US Army clothing, he was at risk of being shot by snipers, while US Phantom bombers were dropping napalm nearby. There was no escaping the ongoing fighting as the opposing forces attacked using grenades and machine guns at close range. Eventually the US declared military victory, but the city was virtually destroyed. More than 5,000 civilians were killed and many soldiers lost their lives, which negatively affected the American public’s perception of the war. Images by photographers such as McCullin helped to inspire widespread demonstrations against US involvement and they have shaped Western perceptions of the conflict to this day. In 1973 American troops were withdrawn, and in 1975 South Vietnam fell to a full-scale invasion by the North.

Cambodia

Cambodia was regarded as no more than a sideshow to Vietnam, and, in consequence it received little attention. As Vietnam faded from the news, Cambodia disappeared almost without trace. Yet… the country was literally being torn apart.

Don McCullin

The Sunday Times Magazine sent McCullin on several assignments to cover the Cambodian Civil War. The military conflict ran from 1967 to 1975. It primarily pitted the Communist Party of Kampuchea (the Khmer Rouge), their communist allies in North Vietnam and the Viêt Công, against the Kingdom of Cambodia.

During the Vietnam War, the Cambodian government allowed communist North Vietnamese guerrillas to use Cambodia as a supply route to their troops fighting in South Vietnam. But in 1970, this government was overthrown, and an anti-communist regime took control. The new government forces fought against the communist North Vietnamese troops in Cambodia and the emerging Khmer Rouge. The US intervened with a bombing campaign targeting the communist forces. However, US bombs also killed large numbers of civilians and significantly contributed to the Cambodian refugee crisis, which saw 2 million displaced people.

During McCullin’s first visit to Cambodia in 1970 he was hit by a mortar bomb. He was seriously injured and others were killed. Returning to Phnom Penh in 1975, McCullin photographed the dire conditions in hospitals. The situation had also become extremely dangerous for journalists, and McCullin knew of at least twenty who had been killed. As the Khmer Rouge closed in on the city, the Sunday Times instructed him to leave and he evacuated a week before the city fell.

The Khmer Rouge, led by dictator Pol Pot, took control of the country in 1975. During their rule, the Khmer Rouge were responsible for the deaths of up to 2 million people. In 1979 the Khmer Rouge were overthrown, and Pol Pot was tried and found guilty of genocide. However, he fled and remained free until 1997, ultimately dying of natural causes in 1998 while under house arrest.

Bangladesh

No heroics are possible when you are photographing people who are starving. All I could do was to try and give the people caught up in this terrible disaster as much dignity as possible. There is a problem inside yourself, a sense of your own powerlessness, but it doesn’t do to let it take hold, when your job is to stir the conscience of others who can help.

Don McCullin

In 1971 McCullin asked to cover the Bangladesh War of Independence after reading about the possibility of a million refugees fleeing into India. At the time, Bangladesh was known as East Pakistan and was under a joint administration with West Pakistan. This was established during the 1947 Partition of India, which saw the end of British colonial rule and the creation of two independent Indian and Pakistani states, based on the religious majorities in both regions. Following a British plan, Partition was a violent act of separation that displaced 14 million people and killed up to 2 million. It set the stage for the Bangladesh War of Independence and continuing tensions between India and Pakistan.

By 1971, Bengali people in East Pakistan were demanding increased autonomy and later, independence. Following demonstrations, thousands of troops arrived from West Pakistan. On 26 March, civil war erupted with West Pakistan’s launch of Operation Searchlight, a military campaign which forced an estimated 10 million East Pakistani civilians to flee to India or face death.

McCullin recounts witnessing an endless flow of people on the road to Calcutta. These refugees were housed in inadequate camps and many people died from starvation as well as wounds from military attacks. With the onset of the monsoons, a cholera epidemic caused further devastation. McCullin photographed the refugees for four days, until his cameras suffered water damage. Despite the difficult conditions, he was determined to show those comfortably at home in Britain how these people were suffering.

On 3 December, India invaded East Pakistan in support of the East Pakistani people, which led to surrender by the Pakistani army. On 16 December 1971, East Pakistan became Bangladesh. Over the course of the war it is estimated that more than 3 million people were killed, and thousands of women were raped. The violence affected almost every family in East Pakistan.

Lebanon

Sir Don McCullin CBE

A Palestinian Mother in Her Destroyed House, Sabra Camp (1982, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Two local newspapermen had been tortured and killed… but the Western press escaped the worst. Even the most murderous factions were keen to impress the justness of their cause upon the world.

Don McCullin

The Lebanese Civil War was a complex conflict which lasted from 1975 until 1990. Following the Second World War the nation gained its independence from France, with the Maronite Christians assuming government control. When the state of Israel was established in 1948, vast numbers of Palestinian refugees fled to Lebanon. This resulted in a shift in the country’s majority religion from Christianity to Islam. Muslim political groups, who already opposed the pro-Western government, allied themselves with the Palestinians. Tensions had been rising for some time and, in 1975, fighting began between the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and Maronite Christians.

Later that year, McCullin travelled to Beirut, the Lebanese capital. Seeking the best access to the fighting, he initially embedded himself with the Christian Phalange militia, witnessing their massacre in the Muslim neighbourhood of Karantina. Shortly after, McCullin and Canadian journalist Martin Meredith were arrested while trying to return to Karantina. ‘I knew then all too well what I had done wrong. I had tried to get through a left-wing Muslim checkpoint by flourishing a Christian [Phalange] pass.’ They were nearly executed as suspected Christian spies, but luckily a senior officer freed them after accepting that they were legitimate journalists.

In 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon in a bid to eradicate the PLO. In September they ordered the right-wing Christian Phalangists to clear out PLO fighters from the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, leading to a massacre of many Palestinian and Lebanese Shiite civilians. The Israeli army had surrounded the camp, blocking exits to prevent people from leaving. As soon as he read about the massacre McCullin returned to Lebanon, arriving about a day later to photograph the aftermath.

Iraq

I don’t believe you can see what’s beyond the edge unless you put your head over it; I’ve many times been right up to the precipice, not even a foot or an inch away. That’s the only place to be if you’re going to see and show what suffering really means.

Don McCullin

After a ten-year break from war, McCullin went to Iraq in 1991. He was on assignment with the Independent, to cover the Kurdish exodus from Iraq in the wake of the Gulf War. Disputes over oil production and Iraq’s historical claims to Kuwaiti territory led to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990. A US-led coalition intervened and liberated Kuwait by February 1991, but stopped short of mounting a full-scale invasion of Iraq.

Towards the end of the Gulf War, the US attempted to weaken Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein by making radio broadcasts encouraging Kurdish rebellion. The broadcasts implied that the US would support a campaign to overthrow Hussein. There was longstanding Kurdish desire for independence, and they had been attacked by Hussein in the 1986–9 Anfal genocide, which killed approximately 50,000 to 100,000 people.

In 1991, uprisings broke out in the south and the Kurdish-populated north. Despite initial success, anticipated support from the US did not materialise and Hussein was able to regain control. In the aftermath, between 1.5 and 2 million people in northern Iraq fled across the borders into Iran and Turkey. Hussein’s helicopter gunships deliberately attacked these fleeing civilians, while many more were killed or injured by landmines planted in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq War. McCullin joined the Kurds as they were fleeing north and were driven up the mountains by the Iraqi army. Three foreign correspondents, who were initially with the same party, were taken prisoner. One was killed on the spot by Iraqi soldiers, while the others were imprisoned for eighteen days. McCullin escaped with the Kurdish fighters and eventually returned to Iraq in 2003 to cover the invasion by a combined force of troops from the US, the UK, Australia, and Poland.

India

It was so easy to fall in love with India; its ancient culture and long history… I have been back again and again many times since and never cease to wonder at the beauty to be found there.

Don McCullin

McCullin first went to India in 1966. He returned throughout his career, taking pictures of the country he finds to be one of the most visually exciting in the world. For many years he made the annual pilgrimage to the Sonepur Mela, a cattle fair that takes place each November on Kartik Poornima, the day of the full moon. Sonepur is located where the sacred rivers Ganges and Gandak meet. Hindus regard it as a holy site. The town is associated with a Hindu festival that celebrates the mythological battle between an elephant and crocodile. The story goes that the elephant was tiring in his long struggle and about to drown. He called out to the Lord Krishna who appeared on an eagle and killed the crocodile. Each year, thousands flock to Sonepur to show their devotion to Krishna and visit the fair. As elephant numbers diminish, visitor numbers have risen. McCullin has photographed the supplicants and pilgrims who gather at similar fairs and holy festivals across India. These include Prayagraj (formerly Allahabad), Sagar Island, Pushkar and Kolkata (formerly Calcutta).

Southern Frontiers

Those colossal Roman stone structures from 2,000 years ago filled me with awe, then it dawned on me how they were achieved. Through cruelty. Through wickedness and slavery. The staggering accomplishment was the product of brutality.

Don McCullin

For many years McCullin has been engaged in an encyclopaedic project to photograph the ruined buildings on the southern borders of the Roman Empire. He has travelled through Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. His photographs document the ruins of a long-gone era, an empire that could only reach such heights through military conquest, slavery and injustice. Though McCullin had previously declared he would not photograph another conflict, he recently returned to Syria to continue to record these sites. He revisited the ruined temple of Palmyra to document the deliberate destruction of these ancient buildings by the so-called Islamic State (IS). Despite having made his earlier images in peacetime, they have become associated with conflict. McCullin’s photographs are now one of the only ways to see these sites as they stood for centuries.

Landscapes

Sir Don McCullin CBE

Woods near My House, Somerset (c.1991)

Tate

My landscapes have become a form of meditation. They’ve healed a lot of my pain and guilt. When I was injured in wars, I thought it was good for me to bleed, to hurt and have pain. Why should I stand over others and photograph their pain and see their blood? The landscape gave me a sense of balance.

Don McCullin

After a lifetime of war, McCullin says he has now ‘sentenced himself to peace’. In recent years, the landscapes of Somerset, Scotland and Northumberland have been McCullin’s focus. Though this photography practice gives him a sense of tranquillity, it is clear that memories of conflict are never far away. His photograph of wars have much in common with his images of the flooded Somerset Levels or Hadrian’s Wall. The jagged, torn earth and dark, metallic skies resemble battlefields rather than peaceful pastoral scenes. For McCullin, these landscapes are politicised too, a result of the constant closures of dairy farms and the development of green belt land.