I have been visiting the Tate Gallery – now Tate Britain – for over fifty years. Sculpture has always been the main attraction for me. Witnessing the shifts and changes in what can be identified as sculpture has been a compelling influence on my relationship with this uncompromising and obstreperous fine art discipline.

From the beginning I was keen to keep pace with the rapidly changing art debates and dynamic influences. As the influence of Marcel Duchamp claimed the intellectual high ground during the late 1950s and onwards, the status of invented form and the hand processes of sculpture became symptomatic of old-fashioned and moral attitudes towards producing art. Questions as to what sculpture could or might be came under rigorous scrutiny. The culmination of those debates was the idea that there was no such thing as sculpture: art was art, and that was that.

From the late 1960s I focused on experimenting with materials and processes, but I could not forsake my ways of making initiated in the early 1960s, based on traditional sculpture processes and where clay was my primary resource.

Dame Barbara Hepworth

Spring 1966

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

View the main page for this artwork

Henry Moore OM, CH

Animal Head 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. This image must not be reproduced or altered without prior consent from the Henry Moore Foundation.

View main page for this artwork

At the time, however, there were issues about sculpture that perplexed me. The ‘hole’ in sculpture, as in Hepworth’s sculptures, and Moore’s, and its idealisation, did not make sense to me. It was claimed that the ‘hole’ changed how the sculpture behaved in space. Maybe, but in the end, for me, it was just a hole. I was more interested in the excavated object where breaking through the surface of its materiality had the potential to destroy the very thing being made. And it is this act of destruction and construction, working together, which has made me re-look at the works I was so captivated by from the 1940s to the early 1960s, and which I encountered when I was first at art school, but then so vehemently rejected.

The sculptural object blocks, interrupts, intervenes, straddles, perches, and above all, occupies the space we might otherwise occupy ourselves. Despite its usually static identity, the sculptural object is restless and unpredictable in how it can use space. It is not necessarily a comfortable or comforting experience.

In the Duveen Galleries I intend to generate a physically demanding encounter which can excite questions about experiencing sculpture – how, why, where, what and when.

Tate’s collection

Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain

© Tate

Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain

© Tate

I am fascinated by the space of the Duveen Galleries, especially the high vaulted roof and the natural light from the windows in the roof and along one side of the galleries.

Martin Creed

Work No.850 2008

Duveen Galleries, Tate Britain

The pounding feet of Martin Creed’s runners combined with the emptied out space of the Duveens created a powerful sculptural experience. The space behind the runners – the space they had just vacated – was as potent as the space they were fleetingly occupying. This ‘emptying out’ is key to how I want to activate the Duveen Galleries’ floor space.

Trojan Asteroid Patroclus

Credit: Lynette Cook and W. M. Keck Observatory

This image of asteroids could have shown boulders, dough, earth or shit for that matter, anything lumpen, but asteroids are ungrounded, which distinguishes them. It is the lumpen form transformed into an ungrounded sculptural ‘lump’ that is important in my proposal.

Bernard Meadows

Armed Bust IV 1963

© The estate of Bernard Meadows

View the main page for this artwork

Hubert Dalwood

Large Object 1959

© The estate of Hubert Dalwood

View the main page for this artwork

I have included in my proposal images of works by British sculptors from the late 1950s and early 1960s such as Meadows and Dalwood who at the time were highly venerated. The Meadows work, in particular, identifies the kind of ugly sculptural form which dominated at the time, and which many an aspiring (British) sculptor then wished to emulate. In contrast, the Dalwood ‘lump’ sculpture has endured for me since I first encountered it in the 1960s.

Jean Arp (Hans Arp) Pagoda Fruit 1949

© DACS, 2002

View the main page for this artwork

Louise Bourgeois Avenza 1968–9, cast 1992

© The estate of Louise Bourgeois

View the main page for this artwork

There were other sculptures from that time, and earlier, which although they also deployed organic, rounded, sometimes ugly shapes succeeded in contradicting the dark, ugly forms as exemplified by the Meadows’ work, and the strict codes of making which came with it: Arp, Richier, Gabo, Hepworth, Moore, Fontana, Bourgeois, Brancusi, David Smith – all of which I acquainted myself with when I was beginning to make sculpture, and all of which revealed a lighter, more visceral, more raw and more spontaneous version of the invented, rounded, ‘lump’ form.

During the 1960s new influences from the USA and Europe percolated into British art. Sculpture begged, borrowed and stole from the welter of possibilities, inundated from across the Atlantic and from across the Channel. The excitement of being unleashed from the rules and regulations of what constituted sculpture (British sculpture) was all embracing – anything and everything was possible.

Eduardo Chillida

Modulation of Space I 1963

© DACS, 2002

View the main page for this artwork

Claes Oldenburg

Giant 3-Way Plug Scale 2/3 1970

© Claes Oldenburg

View the main page for this artwork

And for myself, the freedom to explore different materials and processes not associated with the sculpture I had previously so respected was both invigorating and difficult. There are now works in the Tate collection which exemplify the diversity of sculpture of that time: Chillida, Man Ray, Flanagan, Oldenburg, Robert Morris …

Jean Fautrier

Head of a Hostage 1943–4

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2002

View the main page for this artwork

Lynda Benglis

Quartered Meteor 1969, cast 1975

© Lynda Benglis

View the main page for this artwork

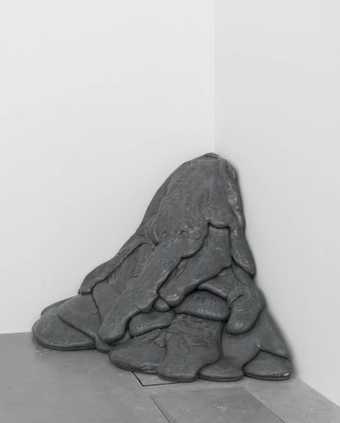

I have also included images of ‘lump’ objects that are of an entirely different order. These are fragile, materially curious objects, lending themselves to transformation and gesture. Fautrier’s scarred and ruined head, Fischli Weiss’s black rubber tree root and Benglis’s poured polyurethane mound, all offer the ‘lump’ in a renewed and re-invented form which is inspirational for its future reincarnations.

Marisa Merz

Untitled (Living Sculpture) 1966

© Marisa Merz

View the main page for this artwork

Rebecca Horn

Concert for Anarchy 1990

© DACS, 2002

View the main page for this artwork

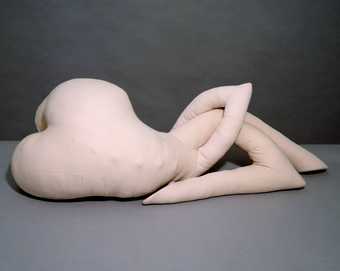

My final images from the Tate collection show some of the suspended sculptures I have seen there. They were instrumental in demonstrating to me how suspended sculpture can be more ambivalent than grounded or plinthed works. The suspended sculpture enables circulating air space above, below and through the works, as if toying with gravity which confuses the identity of what we are looking at. These works can claim to achieve what the much idealised ‘hole’ claims: as well as the Oldenburg and the Morris already referenced, the Nauman, Marisa Merz and the Rebecca Horn take us by surprise, enabling us to be physically active in how we look at both the object and the space in which it is located … and to be witnesses to an altered state of both. (The Dorothea Tanning is, for me, like a collapsed Nauman, and I can also imagine it suspended).

Dorothea Tanning

Nue couchée 1969–70

© DACS, 2002

View the main page for this artwork

Conclusion

I considered that I had rejected the 1940s–1950s and early 1960s sculpture I had been introduced to when I was first at art school. However, looking back, it is clear to me that large forms and awkward structures have persisted throughout my fifty years of making sculpture and their origins lie in my early encounters with those sculptures from the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

My Duveen Galleries proposal is an opportunity to return to that early experience of sculpture. I want to re-claim the ‘lump’ in a revitalised form, to suspend it, to have space circulating around it in an attempt to manipulate its weight and gravity. I want to reconsider the language of the ‘hole’ in relationship to invented form and the ‘lump’, where it is an inevitable result of the processes of making – where the uncompromising ‘lump’ form can be excavated to destruction, expanded, contracted, fractured, poured, drenched, smoothed, roughened, and can be left half finished, polished, burnt, re-built. It can be coming or going, an object about to be or an object that has been. It allows a state of flux and for an unpredictable engagement in the processes of making, uncompromisingly and openly.

In addition, my questioning of how sculpture is viewed and experienced can be represented through the theatricality of the follies of fake balconies, staircases and a stadium-styled seating structure. But most importantly, the ‘lump’ forms, suspended at different heights will be freed from their usual, gravity bound role of floor and plinth where half of their ‘bodies’ remain unseen. These ‘lumps’ will be hung in such a way that, as a group, every aspect of them will be revealed – top, bottom, inside, outside, front, back.

The Duveen floor space, the usual territory for sculpture to be located, will be empty. It will become the audience’s territory, and as such, they will become protagonists on equal terms with the works suspended and hung above them.