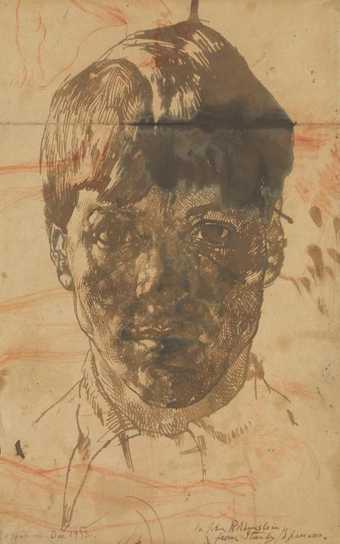

Stanley Spencer (1891–1959) was one of the most original British painters of his generation. His art had two high points: a very early flowering in the years just before the First World War, culminating in his masterpiece Zacharias and Elizabeth 1913–14 (no.14), completed at the age of twenty-two; and the strange, complex period of the mid–1930s, when marital and stylistic crisis propelled Spencer into a flow of extraordinary paintings. Most previous accounts, including Spencer's own, have tended to interpret all the work after 1915 as a quest for some lost wholeness; but it was only through a 'loss of Eden' that Spencer was able fully to participate in the experience of the inter-war years, as well as to embark on an exploration of sexuality and selfhood unparalleled among his British contemporaries.

Sir Stanley Spencer

Zacharias and Elizabeth (1913–14)

Tate

© Estate of Stanley Spencer. All Rights Reserved 2023 / Bridgeman Images

The exhibition is drawn from the whole range of Spencer's achievement. Juxtaposing paintings and drawings, it presents Spencer not as a merely eccentric or provincial English oddity, but as a major twentieth-century artist whose work is linked thematically and stylistically to the painting of his time, and closely engaged with the changing nature of modern experience. There are early religious pictures included here, and works depicting Spencer's military service in Macedonia – an experience that would also generate the great murals painted between 1927 and 1932 for the Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere. However, the images at the heart of the exhibition (rooms 3, 4 and 5) show how a prolonged crisis of the 1930s produced an enormous yet fruitful tension between the once-harmonised visionary and realist strands in Spencer's imagination.

Closing with late works, including Spencer's famous paintings of ship-building in Port Glasgow during the Second World War, and with autobiographical masterpieces such as Love Letters 1950 (no.109), the exhibition charts the insights of an artist exploring and developing across five decades, in what he himself called 'a wonderful desecration'.

Timothy Hyman, artist and writer

Patrick Wright, cultural historian