Paul Nash’s pictures divide themselves fairly easily into groups. Each group centres round a germinating theme.

Each theme is the outcome of a new and fructifying experience, so that his works can be fairly easily dated. The impact of the seashore at Dymchurch in 1923, or of the monoliths at Avebury ten years later, are obvious instances of those new stimuli that were always absorbing him, each one giving him not only new subject matter but also new depth and understanding.

It would be untrue to say that the First World War was the beginning of these stimuli. In a charcoal drawing of 1911, of pine branches against a night sky streaked with the tracks of falling stars, he had already shown that he was romantically aware of the queerness of nature.

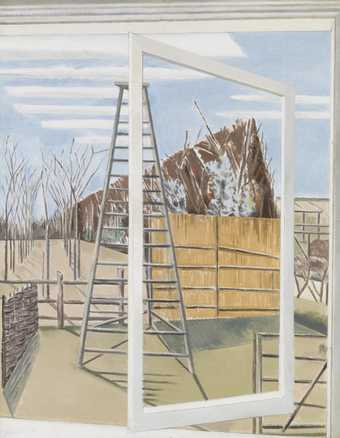

The years between 1918 and 1928 were occupied in a quiet, rather Cezannesque study of English landscape. In this decade he painted his solidest, least spectacular pictures, though suddenly, in the middle of it, the harsh melancholy of the sea front and waves at Dymchurch provoked a memorable series of paintings dominated by a new kind of geometry, a kind of romantic cubism.

But whatever the subject matter there is one constantly recurring obsession which Nash was always trying to reduce to pictorial terms, namely the obsession of the mind’s voyage through space.

It was the same interest in the flight of the mind that led him in 1943 to produce a series of drawings of Aerial Flowers and a remarkable essay explaining their genesis.

During this period, between 1928 and the outbreak of the last war, Paul Nash approached most nearly to Surrealism, though he was never a Surrealist.

In the later stages of the war he returned once more to his own private world: here the parallel with Turner. Turner’s late watercolours have the same confidence and the same elusiveness as Nash’s.

Finally, just before his death, he had planned a series of sunflower pictures in the same mood, only two of which he completed.

Eric Newton