Fiona Banner is fascinated by the near impossibility of containing action and time in a prescribed form. She is best known for making hand-written and printed texts 'wordscapes' or 'still films', that retell in her own words entire feature films or sequences of events[fn]Only the Lonely: Fiona Banner, Bridget Smith exh. cat. Frith Street Gallery, 1997, p.13[/fn]. These personal transcriptions, which began in 1994 with the film Top Gun, also highlight the way in which actual or imagined events are fictionalised and mythologised. In a recent body of work based on Vietnam war films, Banner has deliberately posed questions about the fictionalisation of historical events.In 1997 she published THE NAM 1997, a one thousand-page book comprising her own frame by frame descriptions in continuous text of the Vietnam war movies Apocalypse Now, Born on the Fourth of July, The Deer Hunter, Full Metal Jacket, Hamburger Hill and Platoon. Her texts, representing eleven unbroken hours of harrowing film, hint at the excessive nature of imagery in our culture. When Banner asked a friend to read THE NAM he concluded that in its entirety it was 'unreadable'. This prompted Banner to makeTrance, a twenty-hour, twenty-two cassette unabridged reading of the book in which the action movies unfold in an hypnotic stream of words.

The format of Banner's work is always carefully considered in relation to its content. For example, The desert 1994/95, Banner's retelling of David Lean's epic film Lawrence of Arabia, suggests the panoramic scale of a cinema screen, as well as the vast horizontal expanse of the desert.

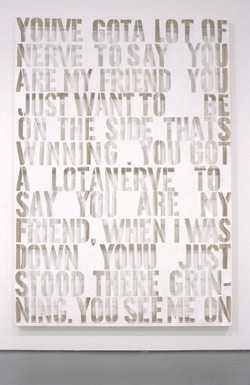

You gota lot of nerve 1998 is inspired by Bob Dylan's classic song Positively 4th Street. With their accusatory use of the word 'you' Dylan's lyrics seem designed to address specific individuals on a widespread scale. The monumental scale of Banner's canvas, and the proximity of its confrontational words to the viewer, suggests that the 'you' in her text is directed personally to each visitor. Banner's rendering of the acrimonious words are incised into the canvas.[fn]Banner's text begins, for example, with the lines:

You gota lot of nerve to say you are my friend, you just wanna be on the side that's winning. You gota lot of nerve to say you got a helping hand to lend, when I was down you just stood there grinning'.[/fn] Ironically this leaves the canvas fragile and vulnerable – the biting words, which bear down on the viewer, are strangely hollow, existing only as negatives or shadows. In this way the artist alludes to what she perceives as the constant power struggle between words and their meaning. Banner is also interested in such seminal and iconic figures as Dylan, who never seem comfortable with celebrity and fail to live up to their own mythic image.

In a series of works based on the genre of the car chase, Banner succeeds in giving visual and literary form to a genre virtually found only in films. The most recent work in this series, Break Point, is based on the chase scene in Kathryn Bigelow's cult film Point Break (1991). The slogan featured in the advertisement for the film was, perhaps accurately in this case, '100% pure adrenalin'. Banner transforms and contains the nail-biting and seemingly endless chase into an arresting landscape of words. As the distance between pursuer and pursued closes, the space between the letters and lines of text stencilled on to the canvas in hazard red correspondingly collapses, until the climax of the chase ends in a crash of words at the bottom of the canvas. But significantly, the chase does not reach completion - when the pursuer finally catches his human quarry, he lets him get away.[fn]Banner describes this moment as follows:

He shouts something and it echoes across, the guy still running jumps at the wire fence, up there he's hanging off it. He turns round and his face is close and breathless, he wants him so badly. Can't shoot, staring the bullet right out, he stares through the crack in his face. He's still down there clutching the gun, he falls onto his back, holding the gun like it's everything. He glances at the other guy high on the fence, then he stares straight up and the bullets volley into the sky.'[/fn]

In 1997 Banner exhibited a neon work in the shape of a full stop, 'the smallest neon in the world'.[fn]op cit Only the Lonely[/fn] Following this she has made a group of enormously enlarged full stops carved in polystyrene. Although varying in size from about two to four and a half foot high they are all enlarged to scale from a variety of such fonts as Courier, Nuptial, Garamond, Blippo, Zapf Chancery, Century and Wing. They each have the same point size but the expanded scale reveals the curious anomalies latent within an apparently universal and uniform symbol.

These sculptures evolved from a group of large-scale pencil drawings of full stops in which Banner attempted to investigate the supposed immateriality or insignificance of a full stop. Sanded down, the white polystyrene sculptures have an illusory surface, their distorted ovoid shapes humorously mimicking the perfect forms of the sculptures of Brancusi. Placed on the floor rather than on plinths, the full stops have to be negotiated as physical objects. The artist has referred to the floor as 'the bottom line'. In this sense visitors might be seen to function as letters mingling amongst the punctuation marks, giving meaning to the spaces between.

The full stop represents an ending but also signifies a beginning, an in between or a gap. Like the polystyrene, which is used as a packing material or 'space-filler', the full stop is transient. The names of the fonts are displayed on accompanying packing boxes, providing a possible titling system for the sculptures. The boxes also reinforce the idea that the full stops are transportable and multilingual.

A full stop denotes the end, and in this sense these works relate to Banner's enduring fascination with the framing or definition of a subject. They also draw attention to the intelligent yet playful investigation of various forms of mark-making, which underpins much of her work.

Text written by Virginia Button

Biography

Born 1966. Lives and works in London. 1986–9 Kingston Polytechnic 1992–3 Goldsmiths College of Art