Frances Hodgkins

Loveday and Ann: Two Women with a Basket of Flowers (1915)

Tate

This exhibition commemorated three distinguished women artists: no claim was made for any similarity of style, outlook or intention; each, however, in her own sphere has made decisive contribution to the history of British painting in the first half of the twentieth century.

In her youth Ethel Walker, who was born in Edinburgh on June 1861, felt no attraction to an artist’s career. She was, indeed, taught drawing and painting in watercolours as necessary accomplishments of a young lady of the time, only to entertain a disinclination to the theory of slavish imitation then prevalent. Not until she was in her twenties did she make the deliberate choice to become a painter, after visiting in Edinburgh a private collection of oriental art, an experience whose force of revelation remained potent with her to the end. It was the Chinese paintings which impressed her most, and their influence, when she was firmly set on her own way, was not displaced by that of the European masters with whose achievement she had in the meantime made acquaintance.

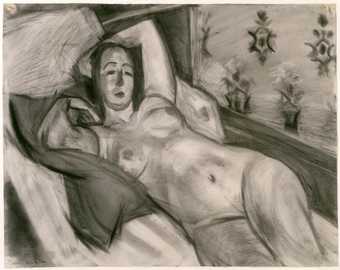

From the start, her drawing was marked by the swift decision of its line, its freedom of gesture tempered with a taut resilience; but in painting she did not immediately reach what is now regarded as her characteristic manner. Her early work comprises many interiors with figures, Rembrandtesque in the dark richness of their tones.

This was heralded by a series of large decorative works, of a kind to which she returned at intervals throughout her career and represented by Nausicaa, The Zone of Love and The Zone of Hate. Dreamlike in their realization of the subject, indeterminate in time and place, they are tinged with a suggestion of orientalism even when dealing with a Homeric theme.

Nature on a more expanded scale she treated in the landscapes and sea pieces mostly painted in the neighbourhood of Robin Hood’s Bay, between which locality and Chelsea she spent the greater part of her working life. Robin Hood’s Bay in Winter, with its distinct tang of weather, well displays her mastery of atmospheric effect.

In her later years, the desire to enlarge yet further her means of expression led her to study sculpture under Professor Havard Thomas. She produced a number of bronze figures, graceful in their deft modelling and of rare plastic quality.

Frances Hodgkins was born in New Zealand in 1869 and died in England in 1947.

When she left New Zealand aged thirty, she had earned enough money to get to Europe partly by giving piano lessons (she had been intended for a musical career) and partly by selling watercolours and doing black-and-white illustrations for the news papers. She had avowedly worked to make money quickly and these illustrations gave little indication of what she was to do later. She left England almost at once and spent her first European summer with a watercolour class in Brittany. But France, too, found her unsettled and uneasy. The freedom that she sought in Europe was difficult to accept because she was still not sure of her own direction. She went to Morocco and, from Tangier, with a native caravan to Tetuan where few white women had ever been. Years later that experience enabled her to turn from Monet, Sisley and Renoir to painters such as Gauguin and Matisse and to interpret their worlds with first-hand vision and originality. She herself regarded the Moroccan visit as the true beginning of her painting career.

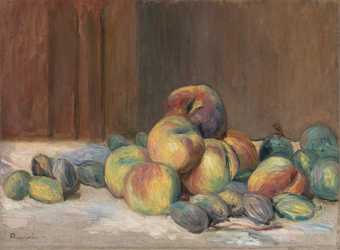

When she first settled in England she began to do portraits, but what was of more interest than the portraits was that she began to develop a free, singing palette and an expressive form of composition that depended on her own imagination for its reality and not upon a clever summing-up of natural appearances. The difference can be seen in the Two Women with a Basket of Flowers, 1915, and the Double Portrait of 1922. The first belongs much more in kind to her work of the first decade of the twentieth century, the second to the beginning of her development after the war, when it became possible to see French pictures again, and when, under the influence of young English artists, she assessed and renewed the impressions that she had got before but had not begun to exploit.

Gwendolen Mary John was born on 22 June 1876 at Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire.

Two events transformed her private life: her long intimacy with Rodin, and her adoption of the Catholic Faith.

Her art has a serenity which was not shaken, but rather enriched, by the various spiritual crises through which she passed.

Not that her work failed to develop. She moved in fact from a technique of painting in glazes or else thin fluid paint, gradually and delicately correcting as she went along, to a use of thick paint applied direct, without reworking.

Nothing could be more restricted than her subjects: her sister-in-law, Dorelia, a few nuns, a few orphan children, herself, some cats, a view from a window. Nor was her treatment of them various: her figures are represented singly and in simple poses; all (except the cats) are chaste and sad. Yet within this range of exceptional narrowness, she produced work that is not only highly original, but capable, no matter how small its scale, of evoking an impression of grandeur and radiance.