Ed Atkins Pianowork 2 2023 © Ed Atkins. Courtesy: the Artist, Cabinet London, dépendance, Brussels, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins Pianowork 2 2023 © Ed Atkins. Courtesy: the Artist, Cabinet London, dépendance, Brussels, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

My life and my work are inextricable. How do I convey the life-ness that made these works through the exhibition? Not in some factual, chronological, biographical way, but through sensations. I want it so the more you see, the richer, more complex, less authored, less gettable things become.

Ed Atkins

Ed Atkins is best known for his computer-generated videos and animations. Repurposing contemporary technologies in unexpected ways, his work traces the dwindling gap between the digital world and human feeling. He borrows techniques from literature, cinema, video games, music and theatre to examine the relationship between reality, realism and fiction.

This exhibition features moving image works from the last 15 years alongside writing, paintings, embroideries and drawings. Together, they pit a weightless digital life against the physical world of heft, craft and touch. Atkins uses his own experiences, feelings and body as models to mediate between technology and themes of intimacy, love and loss.

Repetition and deviation act as structural devices throughout the exhibition. Atkins splits artworks across rooms, repeats them or alters their format. He wants to induce a sense of the familiar made strange, of digression, mistake, confusion, incoherence and interruption. For him, the exhibition represents a reimagining of the messy, unravelling realities of life. The artist introduces rooms and artworks in his own words.

Ed Atkins was born in Oxford, England in 1982. He lives and works in Copenhagen, Denmark.

The first work you encounter is a machine-embroidered patchwork of stained linen stretched over acoustic foam. The barely visible text is a diary my Dad kept while undergoing cancer treatment, bluntly alphabetised into dispassionate nonsense. Throughout the show, embroideries act as material counterweights to the digital videos. Found fabrics, spoiled by use, are stretched to video aspect ratios and covered with unfathomable lists. Where the videos project, the embroideries absorb, putting out silence.

The videos in this room, Death Mask II and Cur, are two of my earliest experiments. I made them right after finishing art school at The Slade. As soon as I started editing footage and sound together on my laptop, I fell in love with the process – what it could contain and the feelings it could express.

I wanted the subject of the camera to recede, allowing the editing, sound, and effects to come to the fore. I started making videos that explored how they were made and how they structured sentiment, confessing their artificial nature while remaining oddly ignorant of it. Slickly edited digital footage is interrupted by messy reality in the form of excess, frustration and accident. These are fragments of unknowable sensation.

I was thinking a lot about the material and emotional extremes of death when I made these videos, as well as the texture of grief. My Dad had recently died, which suffused my life with loss. I wanted to find a vessel and a language to contain these feelings. I began to think of high-definition digital videos as corpses – vivid, heavy and empty. These early short videos are more or less horror films.

Hisser is one of my first entirely computer-generated videos. It was inspired by reading a news story about a man in Florida who went to bed one night only for a sinkhole to open under his bedroom. The earth swallowed him up, and his body was never recovered. I started to fantasise about every story ending like this. Sinkholes opening up abruptly under beds throughout history, throughout literature and cinema. This idea attracted and consoled me.

The video is repeated across three screens of different sizes. The bedroom’s dimensions are modelled to a 16:9 ratio, so it fills the screens perfectly. There’s a confusion of scale: the scene appears like a theatre stage, or an elaborate dolls house with one wall removed. The plasticity and reproducibility of digital video is underscored by the scaled repetition.

The computer-generated character is a customised stock figure from the online 3D marketplace Turbosquid. The character’s facial movements and speech are mine, recorded and mapped using rudimentary performance capture technology. So I am in there too, performing, wearing the figure like a mask or a skin.

Hisser brims with things I wanted to exorcise. Feelings I wanted to see, ordeals I wanted to put the character through. I wanted him to apologise and to be punished, to suffer. It’s around this time that I started calling the characters in my videos ‘surrogates’ or ‘emotional crash-test dummies’. They can cope with things that I cannot. Although our relationship isn’t literal or 1:1, this surrogate is a version of me. The things that happen to it are rehearsals of the unimaginable. O, to be swallowed by the earth and never retrieved.

Refuse.exe is a piece of software that runs across two screens. This is the lower screen, the upper is in a later room of the exhibition. Here, a litany of junk and weather falls onto a stage, accumulating in a great mound of crap. The work is generated live using a modified version of the video game engine Unreal. It’s a physics simulation as proposition – a rudimentary video game that plays itself. Importantly, it is not a recording. Each run-through is scripted but fundamentally different.

I think of Refuse.exe as stripped-back theatre. It was originally conceived as such. I wanted to reduce drama to a grim concentrate. Bin juice. A sequence of things would drop down to an empty stage at dramatic intervals, forming a big pile. I got quite far with these plans – talking with theatres about the load-bearing capacity of their stages, how to stop shards of glass flying into the audience, etc. – but my ideas were ultimately too expensive and impractical. Dramatising a simulation felt like a fantastical alternative.

Lists of things are everywhere in the show. Lists are my favourite kind of literature: flat, objective and pragmatic while remaining abstract, personal and withholding. Refuse.exe is a list of waste. It relates to the ordering of material and psychological things as data, an organising principle that can feel both violently crude and deeply satisfying.

Old Food is a group of looping computer-generated animations among racks of costumes. It stages a pseudo-historic world of peasantry, bucolic landscape and eternal ruin. The characters weep continuously, their lives devoid of dramatic redemption. I had the title Old Food long before I made any of the work. Food seems at such profound odds with the digital. The tears in these videos have the same weird feeling.

I think of these animations and the figures that populate them as things that yearn. They long for the inarticulacies of life – experiences that the technology cannot reproduce. The baby, the boy and the man weep constantly, without cause. They try and fail to speak, gawping imploringly from their screens. They’re me. The costume racks stand between in their thronged masses. I got them from the Deutsche Oper, an opera house in Berlin. The costumes are heavy, soiled husks, absent their animating actors. The audience completes the work as the only living bodies in the room.

Old Food is significant because it’s almost completely devoid of my voice: there’s no speaking or overt lyricism. It marks the beginning of a deliberate impoverishment in my work – the feeling of wanting to speak but not knowing what to say. A universe of foley, sound effects and field recordings blooms in place of speech, a world reported through sound. Eyelids slap and peel, heavy leather creaks and buckles tinkle in caricature. And then the music begins.

Ed Atkins Pianowork 2 2023 © Ed Atkins. Courtesy: the Artist, Cabinet Gallery, London, dépendance, Brussels, Gladstone Gallery, New York and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

Pianowork 2 is an animated recording of me playing Jürg Frey’s ‘Klavierstück 2’ at Mimic Productions in Berlin on 22 June 2023. It was a very hot, early summer’s day. Mimic created a ‘digital double’ of me, scanning my head and hands. It was the first time I’d used a computer-generated figure with my own likeness. I played the piece at an upright piano, wearing a sensor-filled Lycra onesie with a head-mounted rig holding an iPhone a short distance from my face.

I tried very hard to do what Frey’s score asks. I counted the beats in the vast rests, the 468 instances of the same fourth, the precisely instructed micro-shifts of tempo. I worried about and tried to depress the keys with the correct pianissimo dynamic to follow the previous decayed chord played 40 seconds prior. This agonising pace makes for a terrific mounting of anxiety.

My love of pianos comes from my Mum. She plays beautifully, and her repertoire accounts for much of my sentimental taste. Pianos are machines, too, but my identification with them is empathic. My own roboticness, when alone, is often an excuse for instinctive interactions with technology. Performing ‘Klavierstück 2’ is a gorgeous crisis, a worrying that operates between my roboticness and my trembling humanity.

I wanted Pianowork 2 to be as stripped back as possible, to refocus on what I felt was important in my use of digital video. However lifelike the fake, there will always be an irrecuperable remainder. This works both ways: I want to rediscover the human in the most inhuman places.

Nearby are two more machine-embroidered lists. They’re ‘samplers’, spaces of literature. I took two historical lists as my starting points. The first was written by the French artist Antonin Artaud around 1943, scrawled in a notebook while he was interred in a psychiatric hospital in Rodez. The second is by the Japanese author Sei Shonogon, a list of squalid things from around 1000 CE.

I extended both lists using GPT 3, the artificial intelligence language model. This was a relatively early version of the AI – one that felt feral, unpredictable, and slightly frightening. The entries written by GPT 3 are by turns hilarious, impossible and mind-bogglingly violent.

Embroidered, the lists become almost illegible, but I like to think their effects still filter through, like enchantments. My full lists are available to read in the exhibition catalogue, in the reading area outside of the show.

Voilà la vérité is a short video that reworks a single sequence from the 1926 silent film Ménilmontant, directed by Dimitri Kirsanoff. It was digitised from a knackered, toned print lent to me by an archive. I’ve been obsessed with this scene for years – its unaffectedness, the perfect combination of acting and the impossibly real.

I cleaned, colourised, upscaled, smoothed, frame-interpolated, focus-pulled, and re-rendered the footage using a raft of artificial intelligence-employing software. I feel like the resulting video is haunted. It’s a short essay on the history of the moving image as illusion. The title, Voilà la vérité (This is the truth), is the only discernible text in the film: a fragment of a headline on the newspaper that wraps the food.

The foley artist David Kamp performed and recorded a new soundtrack of naturalistic sound – along with less naturalistic elements from me. Two voice actors, Rivka Rothstein and Héctor Miguel Santana, provide the screen characters with new voices. They don’t speak but do sob and sigh and eat. Of course it’s sacrilegious, this forensic, compensatory, fake restoration. It’s a dupe, even if the dupe is a sincere attempt at reanimation.

Ed Atkins, the worm, 2021 © Ed Atkins. Courtesy of the Artist, Cabinet London, dépendance, Brussels, Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, and Gladstone Gallery.

The worm is a computer-generated animation of a phone call between me and my Mum, Rosemary. She is on one end of the line, in England during one of the Covid-19 lockdowns. I’m in a Berlin hotel room, covered in motion capture sensors and monitored by two operators in the room next door. Our conversation is unscripted. We talk about Mum’s relationship with her mother and the inheritance of a perceived unlovability. Feelings passively instilled across generations. This lineage is a worm – Mum refers to it this way in passing, as if it were a creature we all knew and named as such.

I wanted the video to be an artificial documentary of something very much alive and utterly real. The digitally rendered TV studio and smartly dressed figure are references to the British screenwriter Dennis Potter’s last TV interview with Melvyn Bragg in 1994, two months before he died from pancreatic cancer. In it, Potter talks astonishingly about dying and how it italicises the world. Perhaps most famously, he describes the blossom on a tree seen from his window as the ‘blossomest blossom’.

The worm is projected onto an empty birch plywood box, an ominous piece of obscure modular furniture. The video is accompanied by an incidental soundtrack called Love, which plays in the neighbouring room of the exhibition. Sound is everything. The particular quality of Mum’s voice over the phone, the clunk of my mic as I shift position or scratch my nose. Absence and presence, weight, and touch are all reported. In my animations, sound is often a source of excessive, compensatory, confessional materiality.

Ed Atkins, Children 2020–ongoing, © Ed Atkins. Courtesy: the Artist and Cabinet Gallery, London.

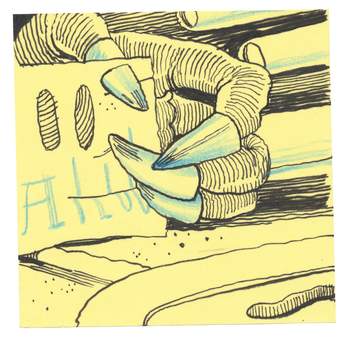

I began making these Post-it note drawings in 2020, during the Covid-19 pandemic. They started as daily additions to my daughter’s lunchbox. Little hellos, little irruptions of love into her day. They were also a way for me to achieve something. Everything I was working on had been cancelled or indefinitely postponed, so the drawings were often the only things I’d make in a day. Unburdened by pretty much anything, they accrued their own importance. I would retrieve them when my daughter got home – often blotched and warped by a satsuma or softened by proximity to a banana – and keep them in a little folder.

My daughter is not impressed or moved by projected significance; she is a child. Her sense of the drawings’ preciousness, or lack thereof, quickly made it apparent that they were mainly for me. I still make them for her, but as with so many gestures towards children, there is a latent unrequitedness I must accept and even enjoy. So much of parenting is sweet mourning – for each and every moment of a child’s life that leaves, never to return, replaced by something new.

I think the Post-it drawings are the best things I’ve ever made. The excuse for their production is unquestionable, founded as it is in love. Their reach towards a marred infinite is also utterly devotional. The designs are desirous, improvised, expedient and dreamy – allied with good dreams. They are divine to me, the cryptic legend at the bottom of the map of this exhibition, and of my life.

Nurses come and go, but none for me is a film in two parts. The first is a performative reading of my Dad’s cancer diary. The second is a reenactment of a role-playing game I play with my daughter called The Ambulance Game, in which she feigns illness and demands a series of fantastical medical treatments.

My Dad, Philip, called his diary ‘Sick Notes’. He wrote it in the six months before his death in June 2009. It’s an astonishing document. An account not only of his illness but also of the personal and public contexts that shape a body’s decline. Feelings of longing and self-pity, the loss of independence, the social life of the hospital, the bureaucracy and administration of terminal illness, and the discovery that he is and has been loved. It’s excruciating and funny, tedious and very sad.

In the film, Peter (Toby Jones) reads the diary to an invited audience of young people. After finishing, he lies down on the floor and pretends to be sick. His partner Claire (Saskia Reeves) treats him by feeding him magical concoctions, covering his face with Post-it notes, discovering diamonds in his vomit, and so on.

The diary and the game were both originally private creations, not subject to public consumption. Despite this, they presume the fantasy of an audience. The film literalises the fantasy by staging the creations as performances.

For Dad, the diary might have been a way to reclaim life through writing, letting go of the details of the world. Similarly, The Ambulance Game is a child’s way of play-acting control through illness and enjoying that control. Like the diary, it’s a rehearsal of the unimaginable. Unlike the diary, once the game ends, the question of recovery becomes irrelevant.