Sir Don McCullin CBE

Shell-shocked US Marine, The Battle of Hue (1968, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Introduction

Since his photograph of 'The Gu’vnors’ was picked up and printed by the Observer in 1959, British photographer Don McCullin has been working continuously both at home and abroad. Spanning sixty years of photography and world events, this exhibition begins in and around the London neighbourhoods where McCullin was raised. It moves into his coverage of conflict abroad, interspersed, as his life has been, with sections covering his trips back to the UK. The exhibition ends with his current and longstanding engagement with traditions of still life and landscape photography. Through this area of his practice, McCullin finds some peace from memories of the cruelty and inhumanity he has witnessed throughout his life.

Unusually for an exhibition of contemporary photography, McCullin has printed every work himself. He is an expert printer, working in his darkroom at home, returning time and time again to produce the best possible prints. In doing so, however, he is forced to revisit painful memories of people and places it is impossible to forget.

Though McCullin is widely known as a war photographer, this title haunts him. He has never been content with the impact made by the images he has produced. He feels they have had an insufficient role in ending the suffering of the people they depict. For McCullin, photography is about feeling. ‘If you can’t feel what you’re looking at’ he says, ‘then you’re never going to get others to feel anything when they look at your pictures’.

Room 1

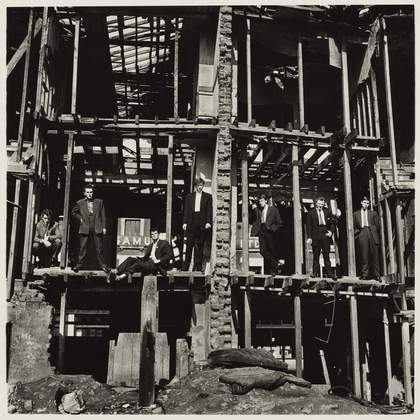

Don McCullin, The Guvnors in their Sunday Suits, Finsbury Park, London 1958 © Don McCullin

Early work

‘I started out in photography accidentally. A policeman came to a stop at the end of my street and a guy knifed him. That’s how I became a photographer. I photographed the gangs that I went to school with. I didn’t choose photography, it seemed to choose me, but I’ve been loyal by risking my life for fifty years.’

Don McCullin grew up in Finsbury Park in north London. At the time, the neighbourhood was still in partial ruins after being bombed in the Second World War. McCullin remembers a childhood of poverty, bigotry and violence. His father died of chronic illness when McCullin was fourteen. His father’s death affected him deeply and he was forced to leave school in order to work to support his family.

McCullin’s life was transformed by his first camera, a Rolleicord bought while on national service with the RAF in north Africa. Much of his early work was made in and around the streets in which he grew up. These scenes included members of a north London gang known as ‘The Guv’nors’ posing in the shell of a bombed-out house. The gang were indirectly implicated in the murder of a policeman and as a result McCullin’s photographs were picked up by the press. It was these photographs which first alerted magazine editors to his intuitive photographic style, securing him his first contract.

From the start, his photographs were unflinching but full of curiosity and empathy for his subjects. Later, when asked why he chose to photograph those who have been harshly treated in life, he said, ‘It’s because I know the feeling of the people I photograph. It’s not a case of “There but for the grace of God go I”; it’s a case of “I’ve been there".

Room 2

Sir Don McCullin CBE

Near Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin (1961)

Tate

Berlin

‘I went straight down to Friederichstrasse and started working with my Rolleicord. Of course, I was sitting on the biggest story in the world, I saw the East Germans drilling the foundations and building the Wall breeze block by breeze block.’

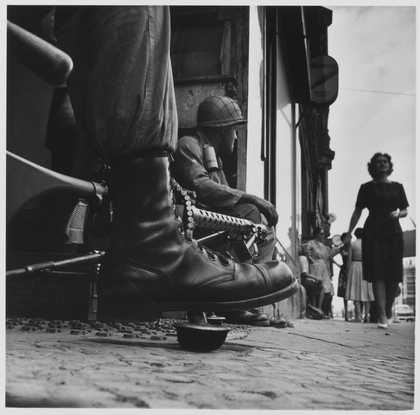

McCullin travelled to Germany in 1961 to photograph the building of the Berlin Wall. After the Second World War, Europe had become a divided continent formed of capitalist countries in the west and communist regimes in the east. The economic situation was significantly poorer in Eastern Europe, with food and housing in short supply, as well as restrictions on individual freedoms. Germany was split into four zones, controlled by Britain, the US, France and Russia. The three western areas formed West Germany. The Soviet-controlled zone became East Germany. The capital city, Berlin, located within the Soviet zone, was similarly divided.

When the border between East and West Germany was officially closed in 1952, it was still possible for some to cross over in Berlin. In 1961 McCullin saw a photograph of an East German border guard jumping over the border to West Berlin. He felt compelled to document the construction of the wall designed to prevent further defections. Without being sent by a newspaper, McCullin was left to pay his own travel costs. The images he took capture the uneasy coexistence of military occupation and everyday life. McCullin’s photographs won him a British Press Award and a permanent contract with the Observer.

Room 3

Sir Don McCullin CBE

Cyprus (1964, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Cyprus

‘Cyprus left me with the beginnings of a self knowledge, and the very beginning of what they call empathy. I found I was able to share other people’s emotional experiences, live with them silently, transmit them.’

In 1964 the Observer Magazine sent McCullin to Cyprus to cover the ongoing violence on the island. It was his first international assignment and the photographs he took were his first images of conflict. His pictures documented a period of violent political conflict between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. There was a long history of both Greek and Turkish rule over the island which had resulted in warfare between the two groups. This conflict became known as a civil war, lasting from 1955 until 1964. Many atrocities were committed and McCullin put himself at personal risk while taking these photographs. He credits the experience as giving him the beginnings of selfknowledge as a photographer, as well as the powerful sense of empathy for which his images are known.

Republic of Congo

‘I first went to the Congo in 1964… The fighting I encountered was vicious and cruel, and on the whole, evil men prevailed.’

Working as a freelance photojournalist for the German magazine Quick, in 1964 McCullin travelled to the Republic of Congo, now the Democratic Republic of Congo. He was tasked with photographing the rebellion which followed the murder of the country’s first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. Lumumba was murdered on 17 January 1961, allegedly with help from the US and Belgium. The assassination took place during a period of unrest following independence from Belgian colonial rule in 1960. The country had fallen under four separate governments: the central government in Léopoldville (which became Kinshasa in 1966); a rival central government by Lumumba’s supporters in Stanleyville (later Kisangani); and separatist regimes in the mineralrich areas of Katanga and South Kasai. Journalists had been banned from Stanleyville, where rebellions were taking place, so McCullin disguised himself as a mercenary working for the Congolese government. Coups and seizures of power followed, resulting in military dictator Mobutu Sese Seko leading the country from 1965 until 1997

Sir Don McCullin CBE

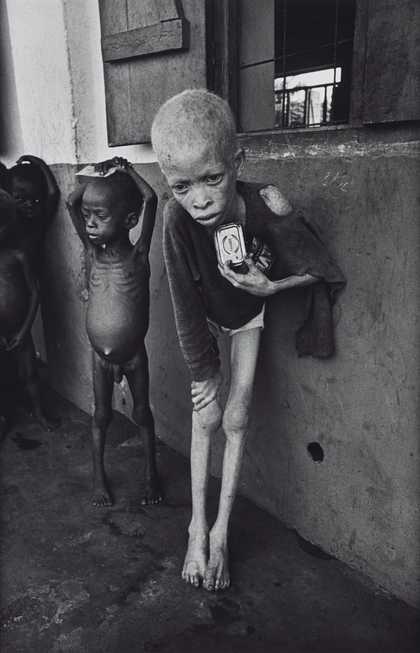

Biafra (1968, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Biafra

‘It was beyond war, it was beyond journalism, it was beyond photography, but not beyond politics… We cannot, must not be allowed to forget the appalling things we are all capable of doing to our fellow human beings.’

McCullin travelled to Biafra in 1968 and 1969 to photograph the humanitarian crisis caused by the Biafran War (now known as the Nigerian Civil War). His work was published in the Sunday Times Magazine. The War was fought between the government of Nigeria and the separatist state of Biafra. It was the result of the deep-rooted political, ethnic and religious tensions in Nigeria. Military coups and control of oil production also played a role. A blockade set up by the Nigerian government meant that food and medical supplies were restricted, causing widespread famine and disease. The federal Nigerian army has also been accused of the deliberate bombing of civilians, mass slaughter with machine guns, and rape.

Reports of starvation and genocide led other countries to call for aid for the people of Biafra. McCullin’s images, and those by other photographers, did much to raise awareness of the situation. However, in December 1969, with increased support from the British government, Nigerian federal forces launched their final offensive. The Biafran state surrendered and was reintegrated into Nigeria in 1970. In three years of war, between 500,000 and 2 million civilians died, many of them children.

Room 4

Sir Don McCullin CBE

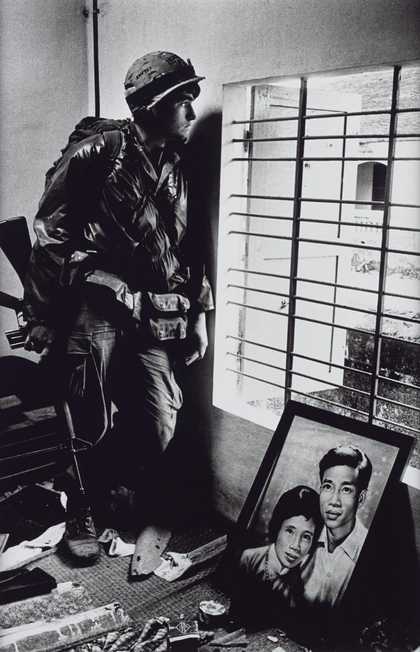

The Battle for the City of Hue, South Vietnam, US Marine Inside Civilian House (1968, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Vietnam

‘Seeing, looking at what others cannot bear to see, is what my life as a war reporter is all about.’

McCullin visited Vietnam sixteen times over the course of his career. Working on assignment for the Sunday Times he covered both the Vietnam War (also known as the American War) and its aftermath. The War was a protracted conflict running from 1954 to 1975. It pitted the communist government of North Vietnam and the Viêt Công, their allies from South Vietnam, against the government of South Vietnam, including the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and its principal ally the US. The Viêt Công fought a guerrilla war against anti-communist forces in the region, while the North Vietnamese Army engaged in more conventional warfare. The US and South Vietnamese forces relied on aerial warfare, including the use of napalm, which resulted in many civilian deaths. It is estimated that between 1 and 3.8 million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians were killed during the conflict. 58,220 US service members also died.

The majority of the works in this room were taken in 1968 when McCullin spent eleven days with American troops. Many of the American soldiers were young, inexperienced and ill-prepared for the horrors they encountered. Their experiences in Vietnam damaged the reputation of the US. McCullin took some of his bestknown images as these men were fighting their way into the citadel during the Battle of Huê, a city in South Vietnam. These photographs were taken the same year North Vietnam launched the Tet Offensive, marking the beginning of the end of the war. In 1973 American troops were withdrawn, and in 1975 South Vietnam fell to a fullscale invasion by the North. Images by photographers such as McCullin helped to draw attention to the war and inspired widespread demonstrations against US involvement.

Cambodia

‘You have to bear witness.

You cannot just look away.’

The Sunday Times Magazine sent McCullin on several assignments to cover the Cambodian Civil War. The military conflict ran from 1967 to 1975. It primarily pitted the forces of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (the Khmer Rouge), their communist allies in North Vietnam and the Viêt Công, against the government forces of the Kingdom of Cambodia.

During the Vietnam War, the Cambodian government had allowed communist North Vietnamese guerrillas to use Cambodia as a supply route to their troops fighting in South Vietnam. But in 1970, this government was overthrown, and a new anti-communist regime took control. The new government forces had support from the US. They fought against the communist North Vietnamese troops in Cambodia and the emerging Khmer Rouge, but gradually lost territory and weakened. In 1975, the Khmer Rouge, led by dictator Pol Pot, mounted a victorious attack on the capital city Phnom Penh. They set up a communist government to rule Cambodia and Pol Pot became prime minister. During their four violent years of power, from 1975 to 1979, the Khmer Rouge tortured and killed those they accused of being enemies of the regime. However it was not until 2001 that a tribunal heard genocide charges against the Khmer Rouge leaders.

During McCullin’s first visit to Cambodia in 1970 he was hit by a mortar bomb. He was seriously injured and others were killed. Returning to Pnom Penh in 1975, the Sunday Times instructed him to leave and he evacuated a week before the city fell to the Khmer Rouge. The regime ended in 1979 with Pol Pot forced to flee.

Room 5

The East End

‘There are social wars that are worthwhile. I don’t want to encourage people to think photography is only necessary through the tragedy of war.’

From the late 1960s to the early 1980s, McCullin photographed communities of men and women living on the streets of Aldgate and Whitechapel in east London. Located at the edge of the wealthy financial centre of the city, the area is unrecognisable today, following extensive gentrification. McCullin began photographing people who he believed had been left living on the streets of following the closure of psychiatric institutions. He lamented the fact that capitalism works against people at the bottom of the social ladder who are unable to fight against its powers. McCullin believes that capitalism led to the closure of these unprofitable institutions which, in turn, left many residents homeless. Far from reflecting objectively on this social crisis, McCullin instead worked closely with the people he photographed. He took several images of a woman called Jean, and his study of her hands is both a testimony to the harsh reality of her living conditions and to McCullin’s connection to his subjects.

Room 6

Don McCullin, Local Boys in Bradford 1972 © Don McCullin

Bradford and the North

‘I wish I’d been born in Bradford, and had its beautiful dialect and its warm, relaxed attitude… Bradford’s full of energy and enthusiasm – an exciting, giant, visual city.’

McCullin was deeply affected by the trauma of reporting from some of the most violent conflicts of the second half of the twentieth century. When he returned home from conflict assignments, he often turned his attention to the tough lives of people in Britain. He photographed communities living in northern cities like Bradford and Liverpool, focusing on areas that had been neglected and left impoverished by policies of deindustrialisation. McCullin saw similarities between their lives and his own childhood. Although he was indeed ‘reporting’ on poverty and social crisis, he also identified deeply with his subjects; picturing the lives of others as a means of learning more about himself.

British Summer Time

‘I couldn’t do without the magnetic head-on collision I keep having every time I go out with my camera in England. It’s become a crusade – just walking for hours, day in, day out, with the camera bag over my shoulder.’

Throughout his career McCullin has spent time capturing the humour, eccentricity and resilience of British people. His images of daily life in England reveal the personalities of the people he photographs, something he achieves through his ability to connect with his subjects. The photographs in this section include images of knobbly knees competitions and persevering sunbathers. Despite their everyday subject matter, like most of McCullin’s work these images continue to highlight social inequalities.

Sir Don McCullin CBE

Northern Ireland, Londonderry (1971, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Northern Ireland

‘One day a sniper, hidden among the stone-throwers, killed a soldier with one bullet… Now it was serious. Returning to my hotel, I had to cross the military lines and suffer the hostile accusations of British troops for aiding and abetting the rioters and ultimately the IRA terrorists. It was inconceivable at the time that the carnage would continue unabated for another twenty five years.’

In 1971 the Sunday Times Magazine sent McCullin on one of many assignments to Northern Ireland. His photographs were published as part of a photo-story entitled ‘War on the Home Front’. They document a period of intense political violence during the thirty-year conflict known as the Troubles.

In the late 1960s, civil rights campaigns to end discrimination against the minority Catholic population of Northern Ireland resulted in accusations of police brutality. Subsequent rioting and violence led to the deployment of the British army and an escalation in the violence in the region. The resulting armed conflict became known as the Troubles. It was fought between republican paramilitaries such as the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), who wanted the six counties of Northern Ireland to be ruled by the Republic of Ireland, unionist paramilitaries such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), who remained loyal to the union of the United Kingdom, and British state security forces, including the British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). The conflict was mostly fought on the streets, with violence often flaring up in residential areas where segregated Catholic and Protestant communities met. More than 3,500 people were killed and up to 50,000 were injured during the Troubles, the majority of whom were civilians.

In the 1990s a series of negotiations took place between the British and Irish governments, and the unionist and republican political parties. Temporary ceasefires and attempts to decommission weapons followed. In 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was finally signed, marking the end of the Troubles.

Room 7

Projection Room

The other rooms of the exhibition feature black and white gelatin silver prints, printed by McCullin in his darkroom at home. But his work was most widely shown to the public in the Observer and the Sunday Times magazines. McCullin worked at the Sunday Times Magazine for eighteen years. The magazine accompanied the Sunday Times newspaper and was the first colour supplement to be published in the UK. From the early 1960s until the early 1980s, photographers like McCullin helped the magazine develop a reputation for the way it combined journalism with high-quality images.

This room shows some of these magazine spreads which include examples of McCullin’s colour photography, and stories not featured elsewhere in the exhibition. Organised chronologically, these fifty-two magazine covers and articles provide a sense of how his work was originally seen, at Sunday morning breakfast tables across Britain.

Room 8

Sir Don McCullin CBE

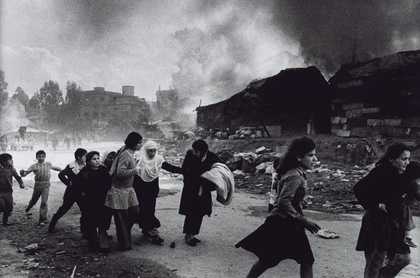

Palestinian Refugees Fleeing East Beirut Massacre (1976, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Bangladesh

‘No heroics are possible when you are photographing people who are starving. All I could do was to try and give the people caught up in this terrible disaster as much dignity as possible. There is a problem inside yourself, a sense of your own powerlessness, but it doesn’t do to let it take hold, when your job is to stir the conscience of others who can help.’

In 1971 McCullin travelled to Bangladesh and India. He covered the Bangladesh War of Independence, which was fought over nine months that year. At the time, Bangladesh was known as East Pakistan and was under a joint administration with West Pakistan. By 1971, Bengali people from East Pakistan were demanding increased autonomy and later, independence for East Pakistan. Following demonstrations, thousands of troops arrived from West Pakistan. On 26 March, civil war erupted, pitting the West Pakistani army against the uprising East Pakistani people.

The Pakistani government launched Operation Searchlight, a military campaign which forced an estimated 10 million East Pakistani civilians to flee to India or face death. These refugees were temporarily housed in camps which were inadequately prepared for the vast influx of people seeking sanctuary. As well as suffering from wounds sustained during attacks in East Pakistan, people died of starvation. With the onset of the monsoons, a cholera epidemic swept through the camps causing further devastation. On 3 December, India invaded East Pakistan in support of the East Pakistani people, which led to surrender by the Pakistani army. On 16 December 1971, East Pakistan became Bangladesh. Over the course of the War it is estimated that more than 3 million people were killed, and thousands of women were raped. The violence affected almost every family in East Pakistan.

Beirut

‘The photographic equipment I take on an assignment is my head and my eyes and my heart. I could take the poorest equipment and I would still take the same photographs. They might not be as sharp, but they would certainly say the same thing.‘

The Lebanese Civil War was a complex conflict which lasted from 1975 until 1990. It resulted in many fatalities and displaced people. Before the Civil War, Lebanon was made up of and ruled by a culturally and ethnically diverse group of people. Most of the people in the coastal cities were Sunni Muslims and Christians, with Shia Muslims in the south and east, and Druze and Christian populations in the mountainous regions. However, the country’s proWestern parliamentary structure was biased towards Christians. When the state of Israel was established in 1948, vast numbers of Palestinian refugees fled to Lebanon. This resulted in a shift in the country’s majority religion from Christianity to Islam. Left-wing pan-Arabist and Muslim Lebanese groups, who already opposed the pro-Western government, allied themselves with the Palestinians. Tensions had been rising for some time and, in 1975, fighting began between the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and Maronite Christians. Later the same year, Palestinian civilians travelling on a bus in Beirut were killed by Christian Phalangists.

In 1976, in the midst of vicious fighting between Christian and Muslim militias, McCullin travelled to Beirut. In January 1976 there had been massacres at Karantina, a mostly Muslim area, and Damour where PLO members attacked a Christian town. In 1982, McCullin returned to find similar scenes. Israeli troops had invaded southern Lebanon and surrounded Sabra and Shatila refugee camps, to prevent people from leaving. Right-wing Christian Phalangists carried out massacres which resulted in the deaths of thousands of mostly Palestinian and Lebanese Shiites.

Iraq

‘I don’t believe you can see what’s beyond the edge unless you put your head over it; I’ve many times been right up to the precipice, not even a foot or an inch away. That’s the only place to be if you’re going to see and show what suffering really means.’

McCullin went to Iraq in 1991. He was on assignment with the Independent, to cover the Kurdish exodus from Iraq in the wake of the Gulf War (1990–91). Iraq had been at war for much of the previous decade. On 22 September 1980, Saddam Hussein, president of Iraq, had led an invasion of Iran, starting a war that would last eight years. He wanted Iraq to replace Iran as the dominant state in the Persian Gulf. He took charge of oil-rich areas over which there had been a long history of border disputes. The UN brokered a ceasefire in 1988, but not before Saddam Hussein had used chemical weapons against the Kurdish town of Halabja, killing an estimated 5,000 civilians.

Following Saddam Hussein’s defeat in the Gulf War, he again turned his attentions to the Kurdish people living in Iraq. In March 1991, he crushed a Kurdish revolt in the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, in the north of Iraq. The Kurds had briefly held the city, before being brutally suppressed by Iraqi forces. Iraqi soldiers went from door to door, rounded up men who were marked as possible threats, then detained and tortured them. Between 1.5 and 2 million people in north Iraq, most of whom were Kurds, fled across the borders to Iran and Turkey.

Room 9

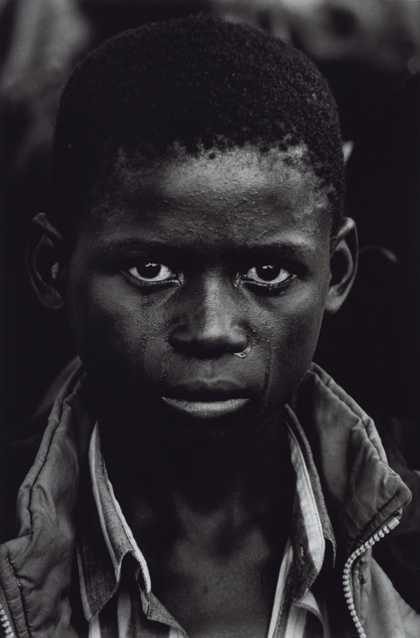

Sir Don McCullin CBE

A Boy at the Funeral of his Father who Died of AIDS, Ndola, Kawama Cemetery, Zambia (2000, printed 2013)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

The Aids Pandemic

‘I want people to look at my photographs. I don’t want them to be rejected because people can’t look at them. Often they are atrocity pictures. Of course they are. But I want to create a voice for the people in those pictures. I want the voice to seduce people into actually hanging on a bit longer when they look at them, so they go away not with an intimidating memory but with a conscious obligation.’

In 2000 McCullin travelled to Africa with Christian Aid to investigate the HIV/AIDS pandemic. His book Cold Heaven: Don McCullin on AIDS in Africa was the result of this visit. It includes portraits of communities and people living through this humanitarian disaster in South Africa, Botswana and Zambia.

India

‘It was so easy to fall in love with India; its ancient culture and long history… I have been back again and again many times since and never cease to wonder at the beauty to be found there.’

McCullin first went to India in 1966. He returned throughout his career, taking pictures of the country he believes to be one of the most visually exciting in the world. For many years he made the annual pilgrimage to the Sonepur Mela, a cattle fair that takes place each November on Kartik Poornima, the day of the full moon. Sonepur is located where the sacred rivers Ganges and Gandak meet. Hindus regard it as a holy site. The town is associated with a Hindu festival that celebrates the mythological battle between an elephant and crocodile. The story goes that the elephant was tiring in his long struggle and about to drown. He called out to the Lord Krishna who appeared on an eagle and killed the crocodile. Each year, thousands flock to Sonepur to show their devotion to Krishna and visit the fair. As elephant numbers diminish, visitor numbers have risen. McCullin has photographed the supplicants and pilgrims who gather at similar fairs and holy festivals across India. These include Prayagraj (formerly Allahabad), Sagar Island, Pushkar and Kolkata (formerly Calcutta).

Don McCullin, People of the Karo tribe 2004 © Don McCullin

Southern Ethiopia

‘When you go to a country, what do you go for? You go to learn, culturally, to absorb, because I left school at fifteen and didn’t have an education, travel and photography has been a blessing to me because it’s allowed me to educate myself and learn about the world.’

In 2003 and 2004 McCullin travelled to the Omo River Basin in south-western Ethiopia, near the border with southern Sudan. The Omo River flows from the central highlands of Ethiopia, home to Coptic Christian communities, until it reaches Lake Turkana in Kenya. Around the course of the river live the Kara (also known as Karo) and the Suri (also known as Surma) peoples. For the past twenty years, both groups have been subject to ethnic tensions and punitive governmental policies, which put their way of life at risk.

Men of both communities have been forced to invest in arms as a result of these hostile governmental policies. Land has been confiscated by the government, restricting people to smaller territories which are often split by newly built roads. With their economy mostly based on cattle, this loss of land means fewer areas for their livestock to graze. Under such pressures, conflict has arisen between different ethnic groups. The combination of these struggles mean that the Kara and Suri peoples’ ways of life are under serious threat of disappearing altogether

Room 10

Don McCullin, Woods Near My House, c.1991 Tate Purchased 2012 © Don McCullin

Still Life

‘So, there is guilt in every direction: guilt because I don’t practice religion, guilt because I was able to walk away while this man was dying of starvation or being murdered by another man with a gun. And that I am tired of guilt, tired of saying to myself: ‘I didn’t kill that man on that photograph, I didn’t starve that child.’ That’s why I want to photograph landscapes and flowers. I am sentencing myself to peace.’

Since the 1980s, McCullin has engaged with traditions of still life photography in order to escape his memories of war. McCullin assembles these still life scenes in the peace of his garden. He uses bronzes collected on assignments abroad, as well as mushrooms and plums grown nearby. He has described the process of putting these together as being ‘akin to receiving a transfusion’. The escapism of the process refreshes and renews him.

Landscapes

‘I dream of this when I’m in battle.

I think of misty England…’

After a lifetime of war, McCullin says he has now ‘sentenced himself to peace’. The landscapes of Somerset, Scotland and Northumberland have been his focus in recent years. Though this photography practice gives him a sense of tranquillity, it is clear that memories of conflict are never far away. His photograph of the Second World War battlefield of the Somme in France has much in common with his images of the flooded Somerset Levels or Hadrian’s Wall. The jagged, torn earth and dark, metallic skies resemble battlefields rather than peaceful pastoral scenes. For McCullin, these landscapes are politicised too – a result of the constant closures of dairy farms and the development of green belt land.

Southern Frontiers

‘Those colossal Roman stone structures from 2,000 years ago filled me with awe, then it dawned on me how they were achieved. Through cruelty. Through wickedness and slavery. The staggering accomplishment was the product of brutality.’

After a lifetime of war, McCullin says he has now ‘sentenced himself to peace’. The landscapes of Somerset, Scotland and Northumberland have been his focus in recent years. Though this photography practice gives him a sense of tranquillity, it is clear that memories of conflict are never far away. His photograph of the Second World War battlefield of the Somme in France has much in common with his images of the flooded Somerset Levels or Hadrian’s Wall. The jagged, torn earth and dark, metallic skies resemble battlefields rather than peaceful pastoral scenes. For McCullin, these landscapes are politicised too – a result of the constant closures of dairy farms and the development of green belt land.