Edgar Degas

Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1880–1, cast c.1922)

Tate

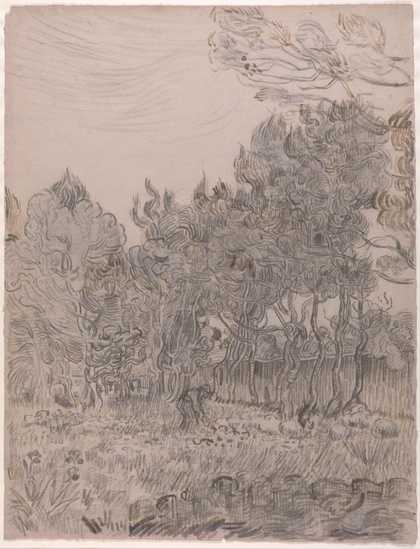

Above all other artists of his time, Degas was able to express himself and his intentions with clarity; that was his aim, and he achieved it by means of the superb draughtsmanship that he so rightly insisted was the essential factor in forming any work of art.

There is no necessity to explain the works of Degas, they are self-explanatory. They show all he wishes us to see and to understand about himself. The influence of Italy, of a classical background, with sound drawing and ordered, serene construction, can be felt from the copies he made of Renaissance masters and from the Young Spartans which, with Semiramis constructing a Town in the Louvre, is the largest and most ambitious of his historical works.

Degas’ masters were in fact the ‘Old Masters’, the painters whom he studied in the Louvre and in his own collection that he formed during his lifetime. He possessed works by El Greco, Cuyp and Tiepolo as well as by Delacroix, Corot, Cezanne, Van Gogh, Whistler, Gauguin and the Impressionists.

The word ‘classical’ recurs constantly in any appreciation of Degas’ work since in some form or other, whether architecturally, sculpturally, constructionally or physically, this quality can be found in almost the slightest scribble left by the artist. He was influenced by Japanese art and by photography in his method of composition, but there is always a grandeur in the achievement, an ordered serenity, that must take the spectator back to a traditional past.

The ‘architecture’ of a picture by Degas with its lines of perspective, of intersection or of mass delineation, in floor boards beneath dancers, in angles of mirrors, panels of doors, pillars and railings in rehearsal rooms, are all as care fully calculated and proportioned as in a has-relief by Ghiberti or a façade by Alberti. Even in the last pastels there is the same nobility as is found in Titian or in Rembrandt or in the late Donatello, when he, like Degas, was almost blind.

The bronzes also cover the whole period during which Degas worked as a modeller. The beauty of these works makes it impossible to say he was not a sculptor in the fullest sense of the word; yet he did use, with the exception of the superb Dancer of Fourteen Years, Dressed, these exercises primarily as aids to his drawing and painting when his sight was failing. When his eyes no longer saw, his fingers could still feel; and most of the bronzes were cast from the wax models of dancers and women washing that he made during the last years of his life.