Cornelia Parker War Room 2015 © Cornelia Parker

Cornelia Parker’s widely celebrated immersive installations have become significant presences in Britain’s cultural landscape. Transforming everyday objects into extraordinary works of art, she pushes the boundaries of what we understand sculpture to be. Rather than carving, modelling or casting like traditional sculptors, Parker collects familiar items which she then squashes, explodes, shoots, burns or turns inside out. The made becomes unmade or remade, and this conversion releases not only a new reading of the object, but in its immersive reassembly, a sense of wonder and awe.

The exhibition brings together almost 100 works, spanning the last 35 years. Revealing the breadth of Parker’s experimental and wide-ranging career, it includes sculptures, film, photography, embroidery and drawing as well as installations.

Parker explores the important social and political issues of our time with wit and a lightness of touch. She uses visual metaphors and storytelling to investigate the nature of violence, ecology, national identity and human rights. The processes by which Parker makes her art are as important as its physical form. She has collaborated with the British Army, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist, the police, a celebrated actor, school children, Texan snake farmers and many others. A key characteristic of her work is the element of chance and lack of control that each alliance brings.

More of Parker’s works spill out beyond the exhibition into Tate Britain’s collection rooms, where they are presented alongside the historical works they reference.

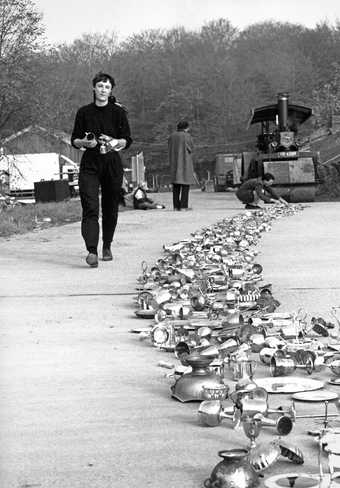

1. Thirty Pieces of Silver

Drawn to broken things, I decided it was time to give in to my destructive urges on an epic scale. I collected as much silver plate as I could from car-boot sales, markets and auctions.

Friends even donated their wedding presents. All these objects, with their various histories, shared the same fate: they were all robbed of their third dimension on the same day, on the same dusty road, by a steamroller.

I took the fragments and assembled them into thirty separate pools. Every piece was suspended to hover a few inches above the ground, resurrecting the objects and replacing their lost volume.

Inspired by my childhood love of the cartoon ‘deaths’ of Roadrunner or Tom and Jerry, I thought I was abandoning the traditional seriousness of sculptural technique. But perhaps there was another unconscious reason for my need to squash things. My home in east London was due to be demolished to make way for the M11 link road. The sense of anxiety lingers even now.

The title was borrowed from the Bible. Thirty pieces of silver was the amount of money Judas received for betraying Jesus.

Cornelia Parker

2. Avoided Objects and Textile Works 1990s–2015

For the small objects I wanted something that was more like a haiku or poem. These works, which might be just as labour intensive as the installations, describe something that was ‘not quite’ an object.

Cornelia Parker

This room offers a glimpse into the rich materiality, processes and inventiveness of Parker’s small sculptures. It brings to light important themes in her work, especially around notions of violence. As well as the subject matter, her processes are also violent: she pulverises, cuts and shoots the objects to make her work. In contrast, the textile pieces appear more ethereal. Constant themes in Parker’s work include references to figures from history, such as in Stolen Thunder, or to the White Cliffs of Dover, as in Inhaled Cliffs.

3. Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View

Cornelia Parker Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View 1991 Tate Presented by the Patrons of New Art (Special Purchase Fund) through the Tate Gallery Foundation 1995 © Cornelia Parker

We watch explosions daily, in action films, documentaries and on the news in never-ending reports of conflict. I wanted to create a real explosion, not a representation. I chose the garden shed because it’s the place where you store things you can’t quite throw away.

The shed was blown up at the Army School of Ammunition. We used Semtex, a plastic explosive popular with terrorists. I pressed the plunger that blew the shed skywards. The soldiers helped me comb the field afterwards, picking up the blackened, mangled objects.

In the gallery, as I suspended the objects one by one, they began to lose their aura of death and appeared reanimated. The light inside created huge shadows on the wall. The shed looked as if it was re-exploding or perhaps coming back together again.

The first part of the title is a scientific term for all the matter in the universe that can’t be seen or measured. The second part describes a diagram in which a machine’s parts are laid out and labelled to show how it works.

Cornelia Parker

4. Abstraction

If I could somehow plumb their depths, tap into their inner essence, I might find an unknown place, which by its very nature is abstract... both representational and abstract at the same time.

Cornelia Parker

Parker consistently works with abstract forms, but she undermines the idea of the non-representational character of abstraction by instilling it with narrative content. Each of the abstract works displayed in this room tells a human story, referring to a particular incident or chance encounter.

An escaped convict in Prison Wall Abstract, the poet William Blake in Black Path, or a battle between life and death in Poison and Antidote provide captivating background and counterpoint to the formal restraint of abstraction, connecting it to everyday life.

5. Perpetual Canon

I was invited to make a work for a circular space with a beautiful domed ceiling. I first thought of filling it with sound. This evolved into the idea of a mute marching band, frozen breathlessly in limbo.

Perpetual Canon is a musical term that means repeating a phrase over and over again. The old instruments had experienced thousands of breaths circulating through them in their lifetime. They had their last breath squeezed out of them when they were squashed flat.

Suspended pointing upwards around a central light bulb, their shadows march around the walls. This shadow performance replaces the cacophonous sound of their flattened hosts. Viewers and their shadows stand in for the absent players.

Cornelia Parker

6. Films

Parker has been making films since 2007. Whether using her iPhone or a drone, single or multi-channel projections, sound or silence, all her films engage with politics in different ways.

Made in Bethlehem is a subtle response to the complexities of politics in the Middle East. On a visit to Palestine just before Easter in 2012, Parker filmed a Muslim man, Muhammad Hussein Ba-our and his son weaving crowns of thorns for Christian pilgrims. War Machine 2015 shows the production of Remembrance Day poppies in a slow reveal, the mechanical process reminiscent of old film reels. The four-channel projection American Gothic, shot on iPhones in New York in October 2016, focuses on the street Halloween celebrations and a rally outside Trump Tower a few days before Donald Trump’s election. The following year, Parker became the UK’s first female official Election Artist. She followed the campaigns with daily observations in over 1,500 images and films on her Instagram feed, which turned into Election Abstract. She also used an eerie night-time House of Commons as the location for Left Right & Centre and Thatcher’s Finger. Parker created FLAG, shot in a Swansea flag factory in February 2022, especially for this exhibition.

Parker’s first film, an interview with the acclaimed philosopher and activist Noam Chomsky about ecological threats and US politics, Chomskian Abstract is shown outside the exhibition in the 1780 room.

7. War Room

I was invited to make a piece of work about the First World War. I had always wanted to go to the poppy factory in Richmond, London. Artificial poppies have been made there since 1922. They are sold to raise for money for ex-military personnel and their families.

When I visited the factory, I saw this machine that had rolls of red paper with perforations where the poppies had been punched out. The fact that the poppies are absent is poignant, because obviously a lot of people didn’t come back from the First World War, and other wars since. In this room there’s something like 300,000 holes, and there’s many more lives lost than that.

I decided to make War Room like a tent, suspending the material like fabric. It’s based on the magnificent tent which Henry VIII had made for a peace summit with the French king in 1520, known as the Field of the Cloth of Gold. About a year later they were at war again.

Cornelia Parker

8. Politics

This is the time we all need to politically engage. We need art more than ever because it’s like a digestive system, a way of processing.

Cornelia Parker

In addition to film, Parker’s commitment to politics and social justice is shown through her photography, sculpture, drawing and the act of collective embroidery, as shown in this room.

Collaboration is central to Parker’s working process. In the Blackboard drawings she worked with school children of different primary school age groups, and Magna Carta (An Embroidery) involved over 200 people, each stitching different key words particular to their situation. They include Baroness Doreen Lawrence, who stitched the words ‘justice’, ‘denial’ and ‘delay’; Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales who stitched ‘user’s manual’ and Edward Snowden who stitched the word ‘Liberty’.

9. Island

When I was a child, we had a market garden and grew large quantities of tomatoes in greenhouses. To protect them from the harsh summer sun we would whitewash the windows.

Later, as an artist, I wanted to find a meaningful material to make whitewash with. The chalk from the White Cliffs of Dover has figured significantly in my work over the years. I love it as a classic drawing material and its role as a patriotic feature of our coastline. It literally marks the edge of England.

For Island I’ve painted the panes of glass of a greenhouse with white brushstrokes of cliff chalk, like chalking time. So the glasshouse becomes enclosed, inward looking, a vulnerable domain, a little England with a cliff-face veil. The Island in question is our own. In our time of Brexit, alienated from Europe, Britain is emptied out of Europeans just when we need them most. The spectre of the climate crisis is looming large: with crumbling coastlines and rising sea levels, things seem very precarious.

The greenhouse sits on a foundation made from worn encaustic tiles (from the Houses of Parliament) that once lined the corridors of power. Their patterns have been rubbed away by cumulative footfalls made by MPs and Lords in the years since 1847.

The light inside the greenhouse slowly pulses, breathing in and out like a lighthouse. The white chalk strokes throw dark shadow moirés on the wall. What is white becomes black, and what was stable is now uneasily shifting.

Cornelia Parker

Cornelia Parker is at Tate Britain from 19 May – 16 October 2022.