Georges Braque was born on 13 May 1882, at Argenteuil, a small town on the banks of the Seine near Paris where many of the great Impressionist painters found inspiration during the 1870s.

After he had completed a year’s military service, Braque persuaded his parents to allow him to renounce the career of peintre-décorateur and to devote all his time to studying art. So, provided with a modest allowance, he settled in Montmartre at the end of 1902 and for the next two years studied at the ‘free’ Académie Humbert, and also briefly (autumn 1903) at the Ecole des Beaux Arts.

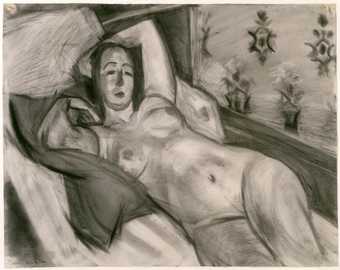

In what he has since referred to as his ‘first creative works’, that is to say his first Fauve pictures, Braque (unlike Picasso) was, therefore, basically concerned with the painting of light. But, through his association with the Fauve movement, Braque (in this, too, unlike Picasso) also fell for a short while under the sway of a more consciously aesthetic conception of painting which was defined at the time (1908) by Matisse in these words: ‘Composition is the art of arranging in a decorative manner the various elements at the painter’s disposal for the expression of his feelings. In a picture every part will be visible and will play the role conferred upon it, be it principal or secondary. All that is not useful in a picture is detrimental. A work of art must be harmonious in its entirety; for superfluous details would, in the mind of the spectator, encroach upon the essential elements.’

It is thus all the more understandable that he should have been ready for the fuller revelation of Cézanne which, when it came (fifty-six pictures by Cézanne were shown at the Salon d’Automne of 1907, and in the same year seventy-nine of his watercolours were shown in the galleries of Bernheim Jeune) opened Braque’s eyes.

After the revelation of Cézanne came the meeting with Picasso and the shock of seeing the Demoiselles d’Avignon. From that moment Braque realised intuitively that his purpose in painting should not be ‘to try and reconstitute an anecdotal fact, but to constitute a pictorial fact’.

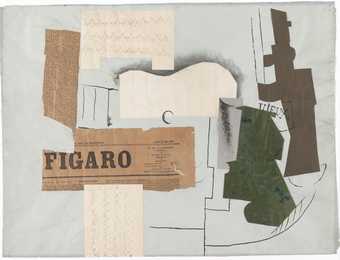

Braque was led by instinct to take the first steps towards the creation of what was soon called Cubism, a manner of painting based on a more matter-of-fact and a less purely visual approach to nature.

Still-life has always been the speciality of Braque’s genius. Seldom has painting been used to confer so much enchantment on such ordinary things: loaves of bread, knives, packets of cigarettes, fruit, flowers, and innumerable domestic accessories.

To quote from the artist’s writings: ‘Without having striven for it, I do in fact end by changing the meaning of objects and giving them a pictorial significance which is adequate to their new life. When I paint a vase, it is not with the intention of making a utensil capable of holding water. It is for quite other reasons. Objects are re-created for a new purpose: in this case, that of playing a part in a picture... Objects always adapt themselves easily to any demands one may make of them. Is it not the poet’s role in life to provoke continual transformations of this, sort on everything around us? Once an object has been integrated into a picture, it accepts a new destiny and at the same time becomes universal. If it remains an individual object this must be due to lack of improvisation or imagination. And as they give up their habitual function, so objects acquire a human harmony. Then they become united by the relationships which spring up between them, and more important between them and the picture and ultimately myself. Once involved in this universality, they all draw closer together, because we have human eyes, and then they refer uniquely to ourselves.’

Douglas Cooper