My ambition is to stretch open the moment at which the paintings are sensed physically and visually, and delay the speed at which they are captured and devoured.

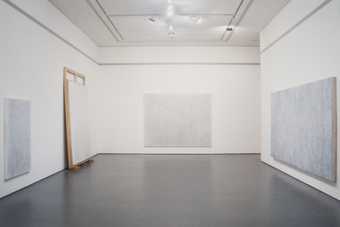

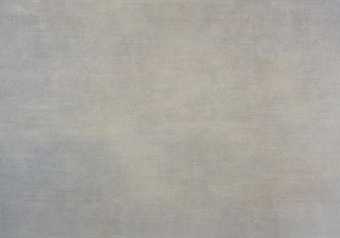

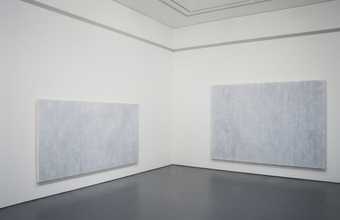

Simon Callery does not want his paintings to be understood, rather he wants them to be perceived, sensed in the same way that the play of light or a textured surface is sensed in the world beyond the gallery. He is driven by a desire to slow down the way we look at paintings, so that the experience of looking takes the form of a genuine physical response. Typically using muted colour, line, rhythm, luminosity and scale, he produces quiet paintings, which he hopes will delay the connection between eye and brain. For Callery, if the paintings are succeeding, they stall, even for just a fraction of a second, the mediated way in which we respond to a painted surface, and hold in check a convention of looking that can dull our senses. This moment is ‘a very special moment, a very particular kind of state to be in. We are absorbing an experience rather than consciously ordering it. This appears to be close to the way I respond when I am outside in the world. Standing in front of art, we are determined to comprehend and process the experience. The more sophisticated we get the quicker we are able to do this. What I am trying to do is negate this kind of processing’.

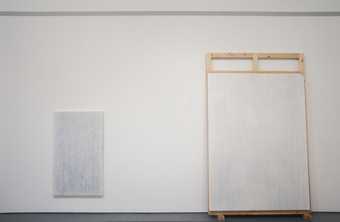

For Callery, the process of making and of looking at a painting are intimately related. Early on, he establishes a physical relationship with his materials. The dimensions of the canvas, for example, usually start from his body height and then expand or contract until the scale is right. He works close to the surface, applying layers of paint and lines drawn in oil pastel with a hand-held straight edge. Then he works the paint and the line with a scalpel. This is repeated until Callery feels the painting begins to have ‘gravity’. His actions are furious, even violent, as he makes conscious adjustments to the ‘faults’ which he sees on the surface of the canvas. This process involves a constant movement to and from the canvas, which for the artist causes a form of amnesia: ‘During the few seconds it takes to walk to the canvas, between deciding what needs to be done and knowing how to do it, I forget. The paintings become an attempt to counteract amnesia. They are the result of countless conscious decisions’. Callery feels that if the painting is working the viewer is also subject to the same ‘amnesia’. He hopes that as the painting gradually unfolds, the viewer’s experience will echo that of the artist in realising the work.

Simon Callery © Tate Photography

Simon Callery © Tate Photography

Callery has always been influenced by his environment. His paintings of the early 1990s were loosely related to the city as viewed from his then fifth floor flat overlooking the Limehouse Basin. They were not depictions of cityscapes, but generalised evocations of the fabric of the city, their luminosity suggesting the effects of light. In 1997 Callery’s interest in light was brought into focus during a six-week Khoj workshop in North India. Participating artists were asked to rely solely on materials from the immediate surroundings. Using local pigments Callery produced a wall painting outside, in the shadow of a large tree. The makeshift paint created a rich, dark surface, but for Callery, the work became the slow, shifting play of light and shadow cast by the tree over the area he had demarcated, light that could be perceived for its own sake.

The experience of working in India also led Callery to explore the question of how to convey the excitement of the studio in the formalised context of a gallery. For example, Spy, an installation exhibited at the British Council in New Delhi, invited the viewer to consider the tension between the private and public nature of making art in a city where the density of the population renders European notions of privacy absurd. The work comprised a constructed room containing the contents of his studio, which could only be viewed through a tiny peephole. The works were placed informally, as if the viewer were witness to the work in progress. For Callery, this piece points to how an awareness of process, the act of making, is central to understanding his intentions.

Callery has often looked beyond the realm of painting to develop and broaden the references of his visual language. In 1997 he took part in the Segsbury Project, supported by The Laboratory at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, Oxford. Callery, in association with photographer Andrew Watson, conducted a systematic survey of an archaeological excavation at Segsbury Camp on the Ridgeway. The survey comprised 378 black and white photographs taken over a period of forty-eight hours, recording the surface of the dig at a particular moment. The images were exhibited in an archive of seven plan chests in the Great Coxwell Barn, Faringdon (Fig. 4), and also assembled to give an overview of the site. The terminology and practice of archaeology connected with Callery’s interest in pacing the flow of information in painting. Horizontality and verticality are key delineators in archaeological practice. A horizontal excavation reveals a layer of one period, whereas a vertical dig uncovers activity over a longer passage of time. Callery was interested in using line to slow down the pace of his work, which at the time was emphatically horizontal. His exposure to the tangible way in which time is perceived on the archaeological site led him to an awareness of how it can function in painting. His increasing use of vertical lines provided a means of slowing the viewer’s experience of the work. Callery has observed: ‘The horizontal line always creates a desire to find depth in a painting. The vertical line draws attention to what is happening on the surface.’ At a certain point in the process of looking, the artist hopes that the eye might take a secondary role. He concludes: ‘In our search to understand, it is ultimately the body that is able to convince us whether or not the subject of our perception is real’.

Text written by Virginia Button (All quotes are taken directly from the artist).

Biography

Born 1960. Lives and works in London.