Muntean/Rosenblum’s work appropriates adolescent figures from fashion or lifestyle magazines, transforming them into strangely compelling scenes which question the possibility of spirituality in contemporary society. Transferred to paintings, drawings and photographs, the affected stances of these youthful models echo the lines ‘She’s over bored, And self assured’ from the cult anthem Smells Like Teen Spirit by Nirvana. Yet behind their studied masks, the figures are full of latent emotions they dare not express: fear, longing, desire and despair. At the core of Muntean/Rosenblum’s practice is what Markus Muntean calls ‘precise ambiguity’. They explore contradictions inherent in the construction of identity and the contemporary notion of self, in works which simultaneously convey absolute banality and spiritual pathos.

Adi Rosenblum comments, ‘We are fascinated by, and investigate, how far you can go with the construction of the gesture of the figure. Because, we think the more artificial it gets, the more moving it is, even though, in the normal sense it is the natural that is the thing that moves you’. The archetypal static poses of these contrived figures are familiar from both contemporary popular culture and art history. Reminiscent of characters from Renaissance paintings undergoing a sublime religious experience, they reflect Christian iconography, much of which refers back to classical art. Yet the only God you imagine these teenagers to follow would be the idols of Carhartt, Converse, Nike, Nokia, Stussy…and so on. Muntean/Rosenblum are following a tradition of figurative painting, calculated to give ‘a certain aura and emotional impact’. But the desolate urban settings seem to negate the possibility of genuine emotion, leaving the viewer with an overwhelming impression of contemporary ennui.

Though Muntean/Rosenblum work in a variety of media, their practice stems from painting. They have been working in partnership since 1992 and have developed a unique joint signature style. Muntean comments, ‘This double authorship has the same function as the white frame or margins, which puts the painting into brackets. These white frames or margins of course have connotations in terms of comics or TV monitors. They allow us to deal with very painterly issues and iconographies, and questions of authorship’. The appropriation of a classical language for their painting distances the treatment of the figures by the artists from the original photographic source material.

Underneath these theatrical scenes run seemingly sophisticated texts which take us by surprise in their sincerity. As in comic art, or film subtitles, we expect the words to be explanatory, yet these disjointed phrases are simply placed alongside, relevant to the image only if we choose them to be. The statements appear to offer poignant commentary on contemporary existence, for example, ‘the certainty that humanity is marching towards a better earthly existence and that a radiant future is just on the horizon. This is well, kind of, mantra of modernism’. These lines of wisdom have also been literally cut and pasted from printed material, found phrases which have the semblance of philosophical statements, but when analysed are revealed to be nothing but jargon.

Somehow we expect the intimate medium of drawing to be characteristic of the individual hand of the artist, yet here the two hands are indistinguishable. The large-scale photographs on view at Gloucester Road tube station present a mise en scene for portrait drawings of teenage fashion models, which lie casually amongst the personal detritus of an artist’s studio. Once again this is a deliberate ploy by the artists to set up an artificial framework that questions notions of subjectivity. In other recent small scale drawings, Muntean/Rosenblum have turned to the language of Russian Constructivist graphics for inspiration with its bold colours and strong forms, finding to their surprise that it is already a strong influence in many contemporary lifestyle and fashion magazines. By referring to such a readily identifiable historic style they take on the political associations of this idealistic movement. An installation of a number of these works, juxtaposed with the portrait drawings, highlights how even the most revolutionary of art movements can be subsumed by mass consumerism, commenting on the futility of utopianism.

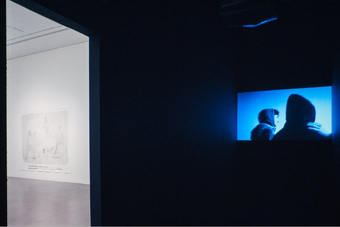

A video work, It Is Never Facts That Tell, made specially for the art now exhibition, takes further the idea of a dystopian vision. The bleak natural landscape, tainted with the intrusive signs of human civilization, contrasts sharply with the emotive classical music. The nostalgic mood of the film, shot in black and white, evokes the lost idealism of a bygone era. The protagonists of the film, the same good-looking young people in trendy outfits who inhabit Muntean/Rosenblum’s paintings and drawings, act out their roles as protesters in a half-hearted manner. They listlessly march along holding banners with cut-out slogans, aware that ultimately their actions will have little effect.

The bold shapes of another new sculptural work, At The Beginning…, also refer to the Constructivist movement. Two arrows direct the viewer around the space, connecting the different elements of the exhibition. The work also offers a resting point, somewhere to stop and contemplate the drawings and paintings on the walls. The phrase printed on the tall flag at the centre point of this three-dimensional work continually defers resolution to the questions raised by the images and text presented in the exhibition: ‘At the beginning we felt like we could change the world, but something happened, then something happened then something happened because something else happened’.

Though their work takes many different forms, Muntean/Rosenblum consistently explore universal themes. Collectively these striking works speak of the way in which longing for individual identity is often expressed through generic codes of fashion and behaviour promoted through the mass media. Ultimately the meaning of the works can never be pinned out, their ambiguity echoing the dilemmas of contemporary society.

Text by Katharine Stout

Biography

Markus Muntean, Born Graz, Austria, 1962

Adi Rosenblum, Born, Haifa, Israel, 1962

They live and work in London and Vienna.