Two jackets hang on the door to Balka's studio in Otwock, near Warsaw. Salvaged from a derelict site and no longer worn, they still denote a human presence, a domestic space. Indeed the studio itself was formerly the family home and was inhabited by Balka's grandmother until her death in 1992. There is no rigid border between Balka's life and his art, but there is always a threshold to be crossed. Here, the exhibition entrance is marked by two steel hooks. From hook to hook around the inside wall of the gallery runs a narrow steel bar at precisely 250 centimetres from the ground, the height to which the artist can reach. This is the horizon line above which is illumination, below which is clarity. Our horizon first becomes apparent at dawn and marks the limit of the night, the start of the day, when shadows first fall. Encounters at dawn are rare for most people but often moving. Awakened at dawn, we hear of extraordinary, private events, of births and deaths. Insomniacs, occasional or habitual, move quietly and without trace through rooms earlier left in repose. In the house in Otwock in which Balka's parents live, items of furniture arranged neatly along the walls bear no trace of yesterday. The carpeted floor, swept clean, is an arena waiting for the events of the day to come.

All is quiet. Elsewhere dawn unveils the trajectory - the tragedy - of the night. Next door to his parents' house is Balka's studio. Here, one morning two years ago, first light revealed the evidence of an accidental fire: mounds of ash and cinders, scorched timbers, blackened wall coverings. Fire, like human life, begins with a spark, a moment of promise, but unlike human life, it is a form of energy which will rage with increasing momentum unless checked. Balka first explored the metaphorical resonance of fire in an early figurative piece called Fireplace, 1987. There the 'fire' was the warmth of the hearth, contained, controlled and welcoming, at the centre of the home. But it was also dangerous, a consumer of flesh after death and, in the context of Polish history, an agent of genocide. Otwock, Balka's native town, was once home to a substantial Jewish population. At the end of the Second World War not a single Jewish family remained. In contrast, Balka's studio fire permitted survivors. Left unscathed in one corner are off-cuts of lino, and in another corner, lying on a stack of trays, are small pieces of soap, dozens of bar ends preserved for recycling.

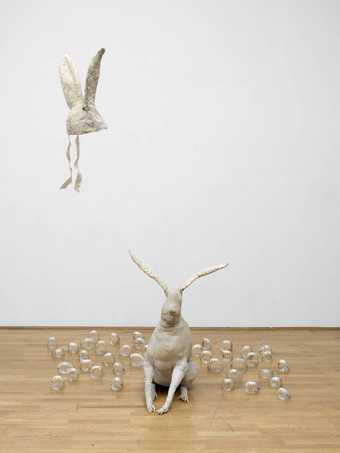

Fire, through the substance of ash, returns continually as a metaphor in Balka's art. Dawn begins and ends with ash. To begin with two parallel steel plates fie close to the floor like beds or tombs. Each is 250 centimetres long, equivalent to the height of the horizon line. Each plate is marked by a groove containing fine grey ash, residue of a previous state of existence now laid to rest, still matter waiting to be transformed into new life. Neither Balka's materials nor his forms are neutral. Although abstract, even minimal, they have a narrative function, through metaphor. They form part of Balka's personal landscape; his art is concerned with bringing the personal and the public, the singular and the universal, into an active relationship. Objects like the bed, a form referred to frequently in Balka's work, bridge this duality. Beds are where we sleep and make love, private and intimate places, but they are also public and institutional, evoking barracks, prisons and hospitals. At the far end of Dawn, placed adjacent to the large steel mesh sculpture, are two linoleum vessels like empty and discarded jars or urns. The presence of mesh evokes a process of refinement, of sieving. The vessels themselves are lined with ash, a material residue that speaks of an earlier function, energy now spent.

Balka's father used to collect the worn-out shards of soap bars and combine them into lumps of soap for re-use, for continued cleansing. Between the two jackets suspended at the entrance to Balka's studio a small sachet containing a refreshing tissue is pinned to the door. Moving from one space to another, shedding garments, washing the body: these are daily domestic affairs and also practices that have assumed important symbolic status within public and private rituals. Like his father Balka recycles soap: the two rectangular rooms in Dawn are lined with it. This is not the luxurious and indulgent product of the perfumery but the pungent, odorous substance that speaks of cleansing and purging. Before arriving at these chambers the visitor encounters two tall steel cylinders. These are both 190 centimetres high -the height of the artist -and are pierced from top to bottom by a narrow slit and by small holes at levels corresponding to breasts and genitals. In Balka's work such piercings denote the obvious bodily orifices but they also stand for pores. The cylinders are lined with salt, a material which emanates from the body in the form of sweat or tears.

A month or so ago while making a newspaper collage Balka came across a scrap of paper under his desk detailing the activities of a 'provincial Polish football team. The team, Balka noticed, was called Swit-Gazownia, which translates as 'Dawn-Gasworks'. So much of Balka's art is inspired by similar singular encounters with ordinary things -things which move him through their ambiguity and associative power. The works, however, are stripped of anecdote and pared down to extremes of formal austerity and expressive sensibility where the mere dimensions, quoted as 'titles', are sufficient to evoke a human presence, and where orientating principles such as vertical and horizontal are enough to stand for life and death. Each new dawn is part of a continuous, circular momentum of real and experienced time. For Balka 'Contemporary time does not exist, we cannot catch the continuous. As we move ever into the future we are always based in the past. This is the state of my sculpture, there is heat from this pillow, and it's impossible to catch, this continuous flow. As soon as you touch it it's colder than it was at its source. Everything we touch is coming from the past, it's our access to death. For me the important thing in my art is to try to catch that consciousness of life'.

Text written by Frances Morris

Biography

Born in Waesaw, Poland, 1958.

Lives and works in Otwock, near Warsaw.

Programme

The 1995-6 exhibition programme is being sponsored by CDT Design and Häagen-Dazs Fresh Cream Ice Cream, with additional support from The Henry Moore Foundation and the Patrons of New Art.