Kate Davis’s carefully composed environments incorporate drawings, collages and sculptural objects. Linking each component is a connection to the body: whether subject to fragmentation and distortion through delicate pencil drawings, literally depicted in photographs or obliquely suggested through a range of adapted readymade objects.

These objects resonate with domestic associations – a door handle, ladder or vase for example – or relate to the technological enhancement of human potential – a bicycle or microphone. Taken out of context, adapted or remade with unlikely materials, they appear at once defamiliarised and loaded with sensory connotations. Furthermore, the human and inanimate are often placed in direct material juxtaposition – flesh against wood or ceramic – or, in common with Surrealist motifs, fused to form hybrid beings, half-man, half-machine.

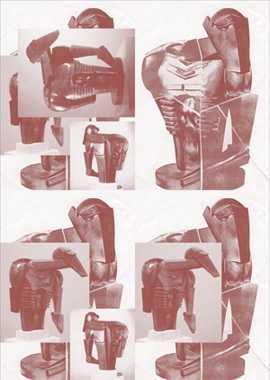

Kate Davis Your Body is a Battleground Still montage 2007

Davis’s project for Art Now offers an idiosyncratic interpretation of two iconic, yet radically contrasting, works: Jacob Epstein’s Torso in Metal from The Rock Drill 1913–14 and Barbara Kruger’s Your Body is a Battleground 1989. Epstein’s Rock Drill, belonging to Tate’s collection, provided the starting point and forms the basis of the photomontage pictured (right). The sculpture was originally conceived as a full length plaster figure designed to sit astride a functioning rock drill – an aggressive and hypermasculine symbol of the new machine age – but was bisected and mutated by Epstein in response to the destruction of the First World War before being cast into bronze. ‘Here is the sinister figure of today and tomorrow. No humanity, only the terrible Frankenstein’s monster we have made ourselves into’1

A series of thirteen snapshots stretches along the corridor wall leading into the main body of the Art Now space. The majority of the images appear to depict ambiguous quotidian scenes bearing little connection to one another, abstracted and estranged through close-up crops or their skewed orientation: an arm bent in repose, the viscous contents of a cracked egg, a naked woman easing herself upwards from a bed, a hand supporting fragments of a broken plate over a wooden tabletop.

In crude marker pen over each image Davis has drawn the hour, minute and second hands of a clock, a rudimentary means, perhaps, of reinforcing the existence of each photographic moment, embedded in real time and specific place.

The corridor of photographs acts as a prelude to the other elements of the installation. A low plinth has been positioned at the centre of the space which supports a section of mattress and bed frame. The mattress has been meticulously cut into a segment the ‘shape’ of ten minutes as seen on a clock face, an absurd attempt to give time tangible form. Slumped forlornly on its haunches, its fabric coating stripped away to reveal its complex internal construction, the bed is still clearly recognisable yet entirely dysfunctional. It is all interior and exterior (one is reminded of the cracked egg), a combination of natural and man-made materials, of hard and soft surfaces.

Pencil-drawn posters adjacent to the sculpture clearly borrow their format and typography from Kruger. Framed by the words ‘too late’ and ‘too early’, Davis’s images show the head and torso of a woman with a random jumble of generic domestic paraphernalia taped crudely to her person – a plastic spatula, metal whisk, swimming goggles – like redundant armour or prosthetic encumbrances. The images operate as a form of flattened sculptural collage in which the body is treated as sculptural object. Davis seems to be testing out the boundaries of the static image while acknowledging, perhaps, the limitations of Kruger’s project; defined by the particular conditions of 1980s consumerism and subsequently criticised for being absorbed by the structures it set out to expose.

The final element of Davis’s project, four black and white photographs documenting a systematic action performed by the artist, is a further attempt to represent time passing and offers a neat link back to the series of thirteen photographs. In one continuous movement, Davis wrote the word ‘still’ in marker pen across the centre pages of a sketchbook before removing a page and repeating the action until no pages were left. The word is never shown complete in the images but in a state of perpetual motion, a continual cycle of disappearance and renewal that reinstates its validity.

By distilling the languages of Epstein and Kruger, Davis revisits specific moments in art history and brings them into the present. Time is treated as an indistinct and elastic entity, a structure to be disrupted. In actively seeking out the fissures and cracks within familiar territories, Davis finds alternative spaces in which to operate. Perhaps in this ambiguous space that is neither present, past or future, yet all three at once, new possibilities can be found.