Jimmy Robert and Ian White 6 things we couldn’t do, but can do now

How and why did you come to work together on this project?

It was as naïve as us going to see Michael Clark perform at the Barbican last year. We both left with a similar idea; that it would be great to work on a performance together. The idea came from watching the dancers walk and run around the stage. We were thinking about the way their arms moved or didn’t move and thinking about how we might come to make a piece where the process was foregrounded and non-spectacular: a process that could be a day trip to Hastings as much as time in a studio. That was on my [Jimmy’s] birthday.

Are the exhibited or performed ‘art object’ and the collaborative process identical in this piece of work?

Is this piece of work identical to the process through which it was made? Yes and no. There is no sense of an ending in the work, just a continuous exchange. In the same way, there are no objects.

When we were working together, mainly in Amsterdam where Jimmy lives right now, we thought a lot about what constitutes work; what might constitute a process that was as much about coming to know each other as it was about finding a way of physically working together. We were coming from very different positions and needing to feel comfortable with each other to make things in ways we hadn’t done before.

The performance and the exhibition represent repeated attempts to do this, in very different forms, but we do not consider either form to be definitive, quite distinct from the way that art objects often feel fixed and finished.

Is there an equivalence between your use of drawing and your use of choreographed movement in the work?

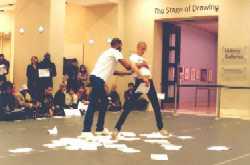

Maybe everything is drawing? There are actual pencil drawings, typewritten text (the automated mark) and then there is also the section in the performance where we physically move each other using pieces of A4 office paper, crumpling each sheet and making a physical impression (these crumpled sheets being the ones pinned to the gallery wall after each performance). There is a relationship between gesture and mark-making. An equivalence maybe, but they are not illustrative of each other. We thought about the relationship between a plan and an elevation in architecture – a virtual three-dimensional model and its map. For example, in ‘Phrase’, the print on the gallery wall the gesture of cutting and threading disrupts representation.

Choreography we understand to be different from movement. This piece of work oscillates between the repeatable action (characteristic of choreography) and movements that are not planned, not strictly repeatable or prescribed. In that sense both the exploration of drawing and the different registers of movement in the performance (random, unintended, choreographed) are perhaps equivalent in their indeterminacy.

How do the presence of the art historical referents you have selected – the Yvonne Rainer piece, the Tate collection work – connect with your own work?

While both these things are connected by their historical status, we actually understand them separately. Learning Yvonne Rainer’s ‘Trio A’ was a very different thing from negotiating with the Tate to hang a work from their/your collection. I [Ian] work mainly as a curator, and I’m interested in the way in which interpretation (always present or mediated for us by the institution or curator when we view a work of art) can be re-pitched as experience, turned into a dynamic rather than passive activity. Attempting to represent a work (dancing ‘Trio A’) with our own bodies, alongside that work’s historical document (the video recording of Yvonne Rainer dancing ‘Trio A’) is interesting and relates to themes of failure, or attempt, which run throughout the piece.

Hanging a work from the Tate collection, on the other hand, became like an enquiry into the institution. It became a way of making manifest our engagement with the museum, of positioning ourselves within it and trying to understand the implications of that – "finding our weight" as Pat Catterson, our dance teacher, would have said.

Are there stories behind the objects you are showing in the exhibition space?

The reason for making the programme notes available, and for the titles of the individual works in the gallery is to make it clear that these objects might come from biographical sources, but biographical narrative is not their content. On one level a kind of personal change has occurred for both of us, but this is private, in the same way as those people we have negotiated the hanging of the work of art with at Tate might have been affected by that process. Both are about the possibility and validity of personal change, without the work needing to make this public in an explicit way. The work, as we said before, is the result of the process but is not necessarily its equivalent.

Could you describe what is at stake politically in the way that your work makes human relations manifest?

We would question the defining line between (physical) actions and (political) activism – between personal change, social change and activism, even. We have no message, but we are engaged in and hoping to give form to a process of exchange. Is it like making an address without a message? Is the performance like spending some time with people as we have spent time with each other?

We don’t know. We could say we know that there are only people in relation to other people, and what is at stake between one person and another person? Maybe everything.

Catherine Wood in conversation with Jimmy Robert and Ian White

Biography

Jimmy Robert, Born France, 1975, Lives and works in Amsterdam

Ian White, Born in Dagenham, 1971