David Thorpe’s body of work to date considers the extent to which pictures, and more recently sculptural objects, offer pathways to new orders of experience. Thorpe considers this constructed ‘world’ of the art object as an ambiguously privileged and paranoid domain. The artist’s earliest work in the mid-late 1990s derived from a fascination with film images. In cutting and pasting coloured sugar paper to make his own pictures, resembling simplified film stills, the artist discovered a method of claiming the promise that such widely-consumed images offered: of building a tangible link between their imaginary world and his existence in real time. These collages conflated romantic cityscapes drawn from American and European films with fantastical projections of the architectural skyline of south east London where he lived, blending local and pop cultural referents.

By forging such links between imagined and ‘found’ imagery, Thorpe began to explore the meeting point between individual agency and the world as a given. Works from 1997 depict large-scale structures which propose the possibility of enjoyment; some by creative ingenuity on the part of the participants, some by design. Silhouetted nightscapes of people at funfairs and in cable cars appeared alongside compositions of ordinary architectural structures re-claimed by city inhabitants: pylons imagined as gigantic climbing frames in Fun or a motorway flyover as viewing spot for a shooting star in Need for Speed.

In the late 1990s, Thorpe’s engagement with his materials began to take on greater complexity, moving towards the dense layering of the current work. Image sources shifted from the city towards grand wildernesses with curious architectural structures set within them. In works such as Out from the Night the Day is Beautiful …, 1999, showing a hang- glider set against soaring pines in a mountain landscape, the increasingly complex arrangement of tiny pieces creates a contoured surface with a resemblance to camouflage.

This thickening of surface in the collages pointed to the moment at which Thorpe’s practice began, productively, to turn in on itself. The work began by reaching towards an existing, but otherwise unobtainable, image world, but after this point the artist’s manipulation of materials had begun to offer endless possibilities of invention itself. Recent collages incorporate all manner of found matter, from tissue paper through to dried bark, mass-produced jewellery, slate, glass and dried grasses and flowers. Yet the current installation, The Colonist, demonstrates the extent to which the artist’s world has expanded from the image world to include the gallery space in four dimensions. Elements of sculpture and architecture are now integral to the work.

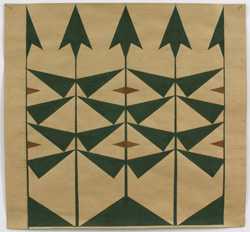

Installed together, the objects and pictures in this exhibition set up complex chains of connection. The sculptures on display double as practical objects which might feature in the world of Thorpe’s images, and as simple aesthetic objects. Resembling a rudimentary weapon, the missile-like shape of Eternity and Resistance echoes an earlier collage of a rocket-like habitation. The bow structure of The Axe Cuts the Root matches the shallow curve of the dam in The Axe Laid on the Root. Other works are akin to provisional models for housing. The White Brotherhood is designed as a miniature ‘lean-to’ containing moveable dowel pieces with the potential for sparking fire. Continuous shifts in scale, from a house pictured in a collage to an abstract architectural model, to a large-scale screen, frustrate the possibility of concrete moments of representational realism. Thorpe’s watercolours appear to offer some truth as ‘pure’ specimens of the natural biology of the world from his vision. But studied closely, these plants themselves are shot through with the geometries of man-made culture. This world is built upon a foundation of human invention and endeavour.

In recent writing, Thorpe imagined the making of art in terms of military defence strategy. In his work, it is not only the constructions of weapons and fortress-like dwellings which place an emphasis on barriers, but also the literal division and separation of gallery spaces by his wood and glass screens titled The Protecting Army I-V. Thorpe’s position in the studio is wilfully isolationist; his own work and the work of others serving as the lifelines of communication and sustenance. His elected ‘advisors’ are books and records by other artists, musicians and architects. Sources range from the English Arts and Crafts movement, particularly in the work of William Morris, to the musical cult of Sun Ra and the writings on self-sufficient communalism by C.R. Ashbee.

Thorpe’s work imagines a cultivated and defended ‘new world’ but he does not work in the tradition of twentieth-century avant-gardism as a revolutionary artist blazing the trail. His work operates with a different level of persuasion, a kind of romantic appeal which points to the possibility of the existence of a pocket of space for building one’s own system of living, one’s own freedom, within an alienating and dysfunctional outside world. In this sense, the work balances carefully on a knife-edge of creativity and conservatism. The work foregrounds a sense of joy in labour as a kind of transformative process. But Thorpe acknowledges the artist-labourer’s position as a luxurious – and therefore necessarily protected, and slightly paranoid – one.

Thorpe’s configuration of images and objects offers a kind of fellowship to those who are open to engage with it, what he has termed a ‘confederacy of seekers’ who wish for such allegiance within a network of historical and current ideas. A performance which Thorpe staged at Tate Britain in 2003, The Mighty Lights Community Project, evoked a similar mood, proposing an imaginary ‘meeting’ of inhabitants of his world. Participants sung hymns and chants on the ambiguously enthusiastic and sinister theme of utopian communal living and belief in a shared, glorious future. The image of community in this work goes against the grain of contemporary notions of ‘participatory’ practice with democratic appeal, implying a certain elitism. Similarly, Thorpe’s work extends a double-edged invitation and warding-off of communality, akin to Sun Ra’s conception of his own philosophy offering ‘a bridge to some, a wall to others’.

Text by Catherine Wood