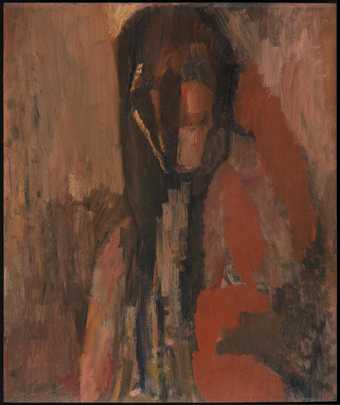

Lucian Freud, Leigh Bowery 1991 Tate © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

All Too Human explores how artists in Britain have stretched the possibilities of paint in order to capture life around them. The exhibition spans a century of art making, from the early twentieth century through to contemporary developments. London forms the backdrop, where most of the artists lived, studied and exhibited. Some of them only ever painted from life, whether focusing on regular sitters, including relatives, friends and lovers, or the everyday landscapes they inhabited. Others selected and combined reference images from a variety of sources to create imagined scenes and suggest possible narratives. Whatever their approach, these artists moved beyond naturalistic representation, capturing the ways in which they are affected by their subjects. Many of the artists in the exhibition have spoken of painting as an activity that cannot be properly expressed in words, existing beyond the limits of verbal language. Embracing the visual and tactile qualities of paint, these artists set out to explore what it is that makes us human.

Room 1

RAW FACTS OF LIFE

Walter Richard Sickert, Nuit d’Été c. 1906. Private Collection Ivor Braka Ltd

David Bomberg, Walter Richard Sickert, Chaïm Soutine and Stanley Spencer worked or exhibited in Britain in the first half of the twentieth century. They inspired the generations of painters that followed them. They established important precedents in their approach to painting due to their subject matter and handling of paint.

This room brings together a selection of each artist's work from a particular moment in their career, when they were each working directly from life or from their own drawings. They painted scenes from their everyday lives and focused on individuals and places that were important to them. They painted surfaces in such a manner as to convey a sense of the material qualities of their subject. They were all, in their own way, seeking to portray as Sickert said, 'the sensation of a page torn from the book of life'.

Room 2

FRANCIS BACON AND ALBERTO GIACOMETTI: FIGURES IN ISOLATION

After the Second World War, Francis Bacon gained recognition for his paintings of isolated and angstridden figures. They seemed to express the sense of loss that followed the devastation of war. By then, Alberto Giacometti had started to focus on his large and slender figures.

Giacometti’s sculptures of solitary beings and Bacon’s figures became identified with existentialism, a philosophical theory that became popular in the post-war period. It was seen as the intellectual expression of anxiety about the fate of humanity in the nuclear age. The gestural quality of Bacon’s brushwork and the imprints left by Giacometti’s hand record the artists’ engagement with their materials. They epitomise the existential condition, with individuals being defined by their direct and subjective experience. Bacon also painted animals, such as dogs and baboons, portraying them as alone and distressed, consumed by the same struggle that he saw as central to human existence.

After the Second World War, Francis Bacon gained recognition for his paintings of isolated and angstridden figures. They seemed to express the sense of loss that followed the devastation of war. By then, Alberto Giacometti had started to focus on his large and slender figures.

Giacometti’s sculptures of solitary beings and Bacon’s figures became identified with existentialism, a philosophical theory that became popular in the post-war period. It was seen as the intellectual expression of anxiety about the fate of humanity in the nuclear age. The gestural quality of Bacon’s brushwork and the imprints left by Giacometti’s hand record the artists’ engagement with their materials. They epitomise the existential condition, with individuals being defined by their direct and subjective experience. Bacon also painted animals, such as dogs and baboons, portraying them as alone and distressed, consumed by the same struggle that he saw as central to human existence

Room 3

F.N. SOUZA: ICONS OF A MODERN WORLD

Like his contemporary Francis Bacon, Francis Newton Souza painted powerful figures whose references spanned a wide range of sources, from early Renaissance paintings to photography, expressing feelings and anxieties of the post-war era as well as reflecting his own personal anguish.

This room focuses on Souza’s work from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, at a time when he lived in London. The graphic power of Souza’s lines produce simplified and bold images, while the thick oil paints applied liberally to the board or canvas, with swift strokes, give his work a sense of vitality and movement. Saints, businessmen and naked figures are some of his main characters, inhabiting a world shaped by loss and desire, as well as spirituality. The erotic nature of his female nudes express the artist’s view of male-female relationships, as complex and shaped by love, lust and abjection. Cityscapes, constructed from fragmented images and memories, are also important subjects and perhaps suggestive of Souza’s cosmopolitan life and frequent travelling.

Room 4

WILLIAM COLDSTREAM AND THE SLADE SCHOOL OF FINE ART: AN ANALYTICAL GAZE

William Coldstream studied at the Slade School of Fine Art and returned there as Professor of Fine Art in 1949. He developed a process in which he attempted to recordreality through measurement, marking the relative location of key features on the canvas. His work was the result of intense scrutiny but also involved empathy, established as he attempted to record another person’s presence through long hours spent painting them.

Coldstream’s approach influenced the artistic practice of many of his students. This influence can be seen in the work of Euan Uglow, whom Coldstream taught in the late 1940s and early 1950s. A similar analytical gaze and insistence on always painting in the presence of the model was also shared by a young Lucian Freud, one of the first artists Coldstream employed as a visiting teacher while Professor at the Slade.

Room 5

DAVID BOMBERG AND THE BOROUGH POLYTECHNIC: STRUCTURE AND MASS

David Bomberg taught day and evening classes at the Borough Polytechnic in south London between 1945 and 1953. In contrast to William Coldstream’s teaching at the Slade, Bomberg did not prepare students for national examinations, which required specific training. Bomberg was critical of traditional observational methods, which he referred to as the ‘hand and eye disease’. He insisted on conveying the tactile as well as visual experience of objects and their mass, emphasising the structure underpinning visual forms.

The way Bomberg taught in life drawing classes and his commitment to drawing outdoors attracted a number of young and eager art students, including Frank Auerbach, Dennis Creffield, Leon Kossoff and Dorothy Mead. After having attended Bomberg’s classes, these artists went on to develop their own individual approaches to painting. They maintained an emphasis on the rendering of the physical experience of a person or landscape, rather than

just a recording of their appearance.

Room 6

AUERBACH AND KOSSOFF: THE CITYSCAPE OF LONDON

Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff both studied at Saint Martin’s School of Art and the Royal College of Art and attended evening classes at the Borough Polytechnic. Despite this shared educational history, they went on to develop highly distinctive approaches, representative of different ways of looking and engaging with reality. What they do share is a deep attachment to London, with works produced from many drawings made over time, rendered as the result of a direct and sustained experience of the city.

Both Auerbach and Kossoff display great sensitivity to the conditions of light, convey the dynamism of city life and reflect the mood of a specific moment. This room brings together paintings of some of the many buildings, streets and sites of congregation painted by Auerbach and Kossoff over six decades, while also signalling the two artists’ continuous engagement with the representation of the human figure.

Room 7

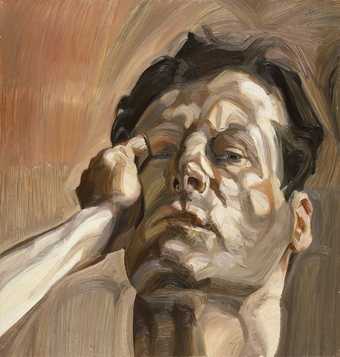

LUCIAN FREUD: IN THE STUDIO

By the 1960s, Lucian Freud had moved away from his earlier artistic approach. Rather than using small brushes he began using bigger, coarser brushes and instead of painting while seated at close proximity to the sitter, he adopted a standing position. This shift in position resulted in high viewpoints that often emphasise the voluminous presence of a body and give a sense of psychological weight. Freud also began to paint full figures and naked portraits more regularly.

The activity of painters usually takes place in the secluded space of their studio. What is distinctive about Freud’s work from the 1960s until his death in 2011, is that the simple, sparsely-furnished space of the studio was not only the space of production, but became the subject of the work itself. While human figures dominate nearly all his pictures, the studio’s walls, painting tools, simple furnishing, mirrors and plants are often equally prominent players within carefully constructed compositions.

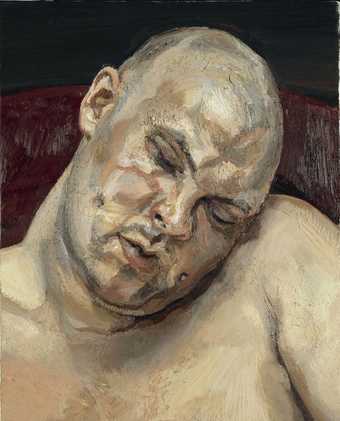

Lucian Freud, Man’s Head (Self-Portrait I) 1963. Whitworth Art Gallery (Manchester, UK) © The Lucian Freud Archive / Brdigeman Images

Room 8

FRANCIS BACON AND JOHN DEAKIN: IN CAMERA

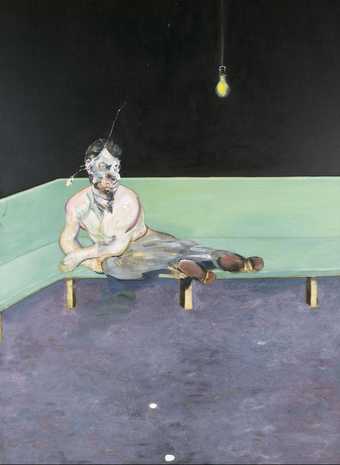

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud 1964. The Lewis Collection

Francis Bacon’s use of a variety of photographic sources in his work, from newspaper clippings to reproductions of paintings and sculptures, has been well documented. He commissioned specific portraits from the photographer John Deakin and took aspects of them as a starting point for many of his paintings from the 1960s and 1970s.

This gallery focuses on Bacon and Deakin’s mutual interest in portraiture. In Bacon’s paintings, bodies swell, contort and reveal their internal organs. Their strong presence is accentuated by the contrast and tension between the colour and texture of the figure and the background. Deakin’s photographs adopt frontal compositions, intimate close-ups, double-exposure and unnatural poses. As a result, his subjects’ bodies seem to be subjected to invisible forces that move or constrain them. Placing Bacon and Deakin’s work together highlights their ability to produce, through their different mediums, striking portraits that convey an intense experience of another person’s physical and psychological presence.

Room 9

ANDREWS AND KITAJ: PAINTING RELATIONSHIPS

Despite having highly different approaches to painting, Michael Andrews and R.B. Kitaj shared a deep admiration for the work of Francis Bacon. Particularly influential in their work was Bacon’s use of a variety of photographic sources, combined to create images capable of expressing the artist’s most intimate desires and concerns.

This room focuses on a selection of Andrews and Kitaj’s work in which the two painters address their fascination with the dynamics of social relationships in compositions of groups of figures, including friends, relatives and close acquaintances. Andrews was primarily driven by existentialist concerns and a deep interest in the different ways people behave when interacting with others. In contrast, Kitaj explored group or collective behaviour through broader social and political concerns. Much of his work includes references to the persecution and resulting displacement of Jewish communities and portrays individuals bound together by a shared personal history.

Room 10

PAULA REGO: LIFE IS THE WILDEST STORY

In the late 1980s Paula Rego began working with live models posing in her studio, producing a series of preliminary drawings before beginning her large-scale paintings. In the 1990s pastel became Rego’s chosen medium. In her work, Rego addresses her desires and fears and confronts memories of personal events, dramatising and vividly depicting them.

Paula Rego

Bride (1994)

Tate

Women’s lives and stories have often been overlooked in art as a historically male-dominated activity. Rego places them at the centre of her work. Women are portrayed as undertaking a variety of activities, in a broad range of moods and temperaments, as victims, culprits, carers, passive observers and sexually-charged creatures. As viewers we are drawn into and become complicit in an unruly world shaped by patriarchal power.

Room 11

IDENTITY, SELF AND REPRESENTATION

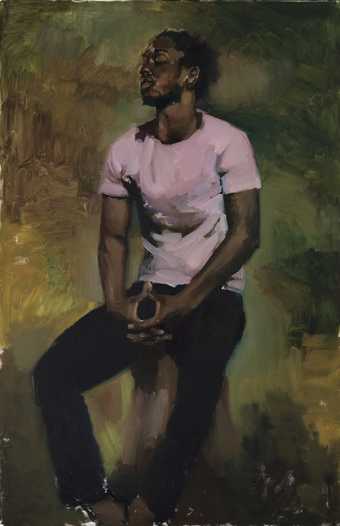

The youngest artists in the exhibition maintain a constant dialogue with their predecessors. Through an engagement with its history, Celia Paul, Cecily Brown, Jenny Saville and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye are knowledgeable of painting as an activity that has constantly evolved.

While Paul is committed to painting from life, Brown, Saville and Yiadom-Boakye paint from a variety of sources. Despite the differences in their approaches, the human figure remains the focus of these artists. Each artist, in their own distinctive manner, embrace the variable properties of oil paint, investigating mark-making, composition, colour and the formal possibilities of painting. In their representations of figures they explore what it is to be human from a contemporary perspective. Throughout their work, they investigate and stretch stereotypical views on femininity, masculinity, race and the many other categories that define and constrain our identity.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Coterie Of Questions 2015. Private collection.